|

pg 61-

Critics of

demic diffusion hypothesis hold that there is no evidence for actual

colonization, that "the predicted rate of farming dispersal under the

hypothesis does not correspond to the observed rate, that there is strong

evidence for continuity between Mesolithic and the Neolithc in most

regions of Europe..", and that Cavalli-Sforza et al confuse the meaning of

the Neolithic in different regions of Europe and attribute a farming

economy to communities that have little or no evidence of farming.

"Consequently, a good case can be made for local adoption of farming by

the indigenous Mesolithic communities in most or all of Europe."

"The underlying problem of the demic diffusion model is that in

order to subject it to mathematical treatment, Ammerman and Cavalli-Sforza

have considerably simplified the complex process of agricultural

transition in Europe."

"Despite widespread support given to these

[demic diffusion] claims, the results emerging from both the gross

morphological and the genetic evidence have been inconclusive at

best."

"Demic diffusion is only one among several types of

population movement which may have contributed to the spread of farming in

Europe; On the other hand, not all indigenists insist on the local

adoption of farming throughout Europe. Scenarios combining limited

population movement and local adoption are certainly possible."

pg 63-

As an alternative to the colonization hypothesis and the demic

diffusion model, an availability model of the agricultural transition was

developed to accommodate the role of the local hunter-gatherer, and allow

for the effects of the agricultural frontier, in a 3 stage process,

availability, substitution and consolidation.. all operating in the

context of an agricultural frontier- a zone of contact and exchange

between foragers and farmers. Such interaction might involve exchange of

people, or exchange of crops, animals, vegetable or meat products, or

material culture. There is also a historical context, ecological

conditions, trade and many other factors, rather than a simple "conquest"

or "colonist" versus indigene scenario. The agricultural frontier might be

mobile or stationary, based on age demographics, land use patterns,

population growth, soil conditions, etc. of the local zone of contact.

pg 69-

Researchers such as van Andel and Runnels argue in favor of the demic

model for the spread of farming for example, but their own calculations

fail to substantiate the population growth rates necessary for such a

model to operate, and contradict the estimates put forth by

Cavalli-Sforza.(pg 69.) |

African agriculture was well underway says John

Reader:

Contrary to the claims of some that African agriculture depended on

demic diffusion from outsiders, historian John Reader shows African

agriculture to be well underway on the continent, without any need for

Near Eastern migrants to "jump start" it. Also contrary to popular

conception, early agriculture in the Nile Valley did not first become

important due to cultivation dependent on the overflow of the Nile River.

The genesis of early agriculture lay in exploitation of the Sahara which

was often lush and green in earlier eras. To this was added exploitation

of the fish resources in many watered areas in this region, including but

not limited to the banks of the Nile. Small scale movement of Near Eastern

domesticates were added to this already established mix, over the

centuries, but in short, the ancient inhabitants of the Nile Valley had a

productive economy in operation long ago, and did not need to wait for

reputed European or Caucasoid migrants or colonist to diffuse the

knowledge of agriculture to them. Furthermore the move towards dynastic

consolidation is from the south to the north, again contradicting claims

of colonization and/or formative "advancement" brought from the

Mediterranean or Mesopotamia, or areas like Palestine, or Lebanon.

Excerpt from Africa: A Biography of the Continent,

by

John Reader, Penguin Books, 1998, pp. 120-173

"Deliberate control of plant productivity dates back to 70,000

years ago in southern Africa, and the world's earliest known centrally

organized food production system was established along the Nile 15,000

years ago, long before the Pharaohs, then swept away by calamitous changes

in the river's flow pattern."

"Agriculture is essentially a process

of manipulating the distribution and growth of plants so that greater

quantities of their edible parts are available for harvesting and

consumption. The world's earliest known evidence of natural resources

having been manipulated in this way comes from archaeological excavations

at the Klasies River cave site in South Africa.."

“The human

populations of Africa which have survived the bad times of the last

glacial maximum were well adapted to take advantage of the good times that

followed. Their archaeological visibility increased rapidly, and a steady

proliferation of rock engraving, painting, and decorative items in the

record points to cultural systems of heightening sophistication. As for

food-production systems underpinning this population growth and burgeoning

cultural sophistication, two innovations are particularly relevant, in

that each represents an important stage of technological development and

both are clues to the future of humanity.”

“The first is the

digging-stick weight, which is simply a large stone with a hole bored

through the middle. The stone fits on the stick and its weight lends added

force as the point is thrust into the ground. Digging-stick weights appear

in the African archaeological record during the last glacial maximum, and

their invention suggests that food-gathering technology had been improved

in response to the greater importance of subterranean foods-roots, tubers,

and corms- during the period of climatic stress. The second innovation is

the projectile point, made for use on the spear or the bow and arrow…..

the evidence of projectile-point technology in Africa pre-dates that from

any other part of the world…..and there can be no doubt that the spear and

the bow would have made hunting a more reliable source of protein and fat

during bad times.”

“The digging-stick represents the beginnings of

agriculture and the trend towards a sedentary way of life. The projectile

point represents a refinement of human capacity for taking

life.”

“Agriculture supported life, and the projectile point denied

it. Both factors were evident during the millennia which followed the last

glacial maximum. In climatic terms, the good times continued

uninterruptedly, and the human population increased exponentially. The

attempts to manipulate food production which mark the beginnings of

agriculture encouraged extended use of areas that previously would have

been visited only temporarily. Successful attempts raised population size

above the carrying capacity of the land.“

“In the course of the

2,000 years immediately prior to the last glacial maximum 18,000 years

ago, the number of sites in the Nile valley increased four-fold; during

the following 2,000 years (18,000 to 16,000 years ago) the number almost

doubled again, and it increased by yet another one-third between 16,000

and 14,000 years ago. By 12,000 years ago, the number of occupation sites

along the Nile valley was more than ten times the number known from before

the last glacial maximum, 6,000 years earlier.”

“Throughout this

period the majority of sites had covered an area about 400 m (the home

base for a group of perhaps forty people), but the size of the largest

rose from 800 m 18,000 years ago to more than 10,000 m 6,000 years later –

large enough to constitute a village.”

“During the 1960’s, an

international team of archaeologists discovered a burial ground about

three kilometers north of Wadi Halfa in the Sudan….Excavations uncovered

the skeletons of fifty-nine men, women and children, who had been buried

in shallow graves under thin slabs of sandstones sometime between 14,000

and 12,000 years ago….Points were found wedged in the spine, and embedded

in the skull, the pelvis, and the limb bons”

"The mainstays of the

system were catfish and wetland (and possible wild grass grains), which

were abundantly available at certain times of the year – catfish in

summer, wetland tubers in winter – when surpluses were harvested and

stored for consumption during the months of the year when food was less

readily available.”

“Harvesting and storage mark the beginning of

organized food production: agriculture. But at that stage of its

development in the Nile valley organized food production was a high-risk

strategy. Output was likely to vary unpredictably, and any increase in

population size resulting from a succession of good years would inevitably

lead to competition in less favorable times. The burials at Jebel Sahaba

(Wadi Halfa) probably record one such episode of violent competition, or

warfare, for limited resources of a less than luxuriant Nile valley that

was surrounded by an utterly inhospitable desert.”

“The adoption of

this broad adaptive strategy provided the large food supply needed by a

growing population, but achieving maximum production called for a good

deal of planning and the management of labour. This marks the beginning of

an organized food-producing system: agriculture.”

“Dating from more

than 15,000 years ago, the evidence from the Nile valley is arguably the

earliest comprehensive instance of an organized food-producing system

known anywhere on Earth. Given time, this pioneering system might have

developed into the stupendous civilizations that ruled ancient Egypt for

two and a half millennia from about 5,000 years ago. But it could never

be. Disaster struck the Nile valley as its population reached a peak, and

by 10,000 years ago occupation density had plunged to a level only

slightly above that known for the time of the Wadi Kubbaniya site.”

New genetic evidence indicates that Africans

domesticated cattle independently of the Near East

Gene Study Traces Cattle

Herding in Africa, by Ben Harder, National

Geographic News, April 11, 2002, retrieved April 7, 2008 from news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/04/0411_020411_africacattle.html

Brief excerpt:

"But new evidence, reported in the April 12 issue of

the journal Science, suggests that Africans independently

domesticated cattle.

Belgian geneticist Olivier Hanotte, who headed the new study, said the

research "reconciles the two schools of thought" about how cattle

domestication occurred in Africa.

"There were Near Eastern influences" on African herds, he said, "but

they came after local domestication."

Since then, there has been considerable mixing of African and Asian

breeds.

Unusual Pattern

In general, the domestication of cattle and other livestock has

followed the establishment of agriculture. But archaeological research has

shown that the domestication of cattle unfolded differently in Africa than

elsewhere in the world.

In many parts of Africa, people herded cattle long before agriculture

was introduced from the Near East and south Asia. Some African groups that

have herded cattle for centuries have never adopted agriculture at all, or

have done so only recently. One example is the Masai of eastern Africa,

who rarely slaughter cattle but instead mix the milk and blood of the

animals to create a staple of their diet.

Intrigued by the uncommon pattern of cattle domestication in Africa,

Hanotte moved to Kenya in 1995 in an effort to explain the development. He

and other researchers in Europe began untangling layers of genetic

information in cattle DNA to help answer major questions about the history

of herding in Africa.

Their findings offer scientists and herders a virtual history book

describing how cattle, crucial to so many Africans, came to be so

genetically diverse. The research also underscores why preserving that

variety is essential.

Hanotte and his colleagues analyzed more than a dozen segments of the

cattle genome. Because the sections they looked at don't affect how "fit"

an animal is evolutionarily, they aren't subject to the effects of natural

selection.

As a result, those genetic segments record the genetic twists and turns

of different cattle lineages and, in the language of DNA, serve as scribes

of bovine history.

The researchers compared this DNA material among many individual cattle

belonging to 50 different herds in 23 African nations. Herders,

scientists, and government officials in those countries aided the study by

tracking down sometimes-remote herds, testing them, and transmitting the

data to Hanotte and his team.

When Hanotte and his colleagues analyzed the samples of cattle DNA,

they found that the variation associated with certain segments of genetic

code reveal a telling geographic pattern across Africa.

The nature of genetic variation changed like the colors of a rainbow as

the researchers looked at cattle from West Africa, Central Africa, and

southern Africa. The greatest amount of genetic diversity was found among

herds in Central Africa.

Based on the data, Hanotte and his colleagues concluded that people

living in Central Africa developed cattle domestication on their own, and

that the techniques—or the herders themselves—gradually migrated toward

the west and the south, spreading domestication across the continent.

Mixed Origins

In looking at the wide genetic variation among African cattle, the

researchers found evidence of interbreeding between cattle native to

Africa and an imported breed.

Most modern African herds represent mixtures of two breeds: Africa's

native cattle, called taurines (Bos taurus), and a slightly larger

Asian breed, known as zebu (Bos indicus), which was domesticated

before it arrived in Africa.

Long-distance trade across the Indian Ocean brought many domesticated

plants and animals to Africa, including the chicken and camel and cereals

such as finger millet and sorghum. Presumably, Hanotte said, trade also

brought zebu bulls that farmers interbred with domesticated taurine cows,

producing the mixed herds of today.

Some variation in the African herds is also attributable to European

influences, Hanotte said. These genetic contributions came in the past few

hundred years, during Europe's colonial influence in Africa.

For thousands of years, animal farmers have gradually improved their

livestock by selectively breeding animals with different desired traits to

endow the offspring with valuable combinations of traits. .."

Full citation: Science 12 April 2002: Vol. 296. no. 5566, pp. 336 -

339, "African Pastoralism: Genetic Imprints of Origins and Migrations,"

Olivier Hanotte, 1* Daniel G. Bradley,2 Joel W. Ochieng,1 Yasmin Verjee,1

Emmeline W. Hill,2 J. Edward O. Rege3 |

More new research shows that Africans independently

domesticated cattle and carried out their own internal "diffusion" of

cattle culture from east to south, independently of Near East or

Europe

Y-chromosomal evidence of a pastoralist

migration through Tanzania to southern Africa

by Brenna

M. Henn, Christopher Gignoux,, Alice A. Lin, et al.

PNAS August 5, 2008

vol. 105 no. 31 10693–10698

Abstract

Although geneticists have

extensively debated the mode by which agriculture diffused from the Near

East to Europe, they have not directly examined similar agropastoral

diffusions in Africa. It is unclear, for example, whether early instances

of sheep, cows, pottery, and other traits of the pastoralist package were

transmitted to southern Africa by demic or cultural diffusion. Here, we

report a newly discovered Y-chromosome-specific polymorphism that defines

haplogroup E3b1f-M293. This polymorphism reveals the monophyletic

relationship of the majority of haplotypes of a previously paraphyletic

clade, E3b1-M35*, that is widespread in Africa and southern Europe. To

elucidate the history of the E3b1f haplogroup, we analyzed this haplogroup

in 13 populations from southern and eastern Africa. The geographic

distribution of the E3b1f haplogroup, in association with the

microsatellite diversity estimates for populations, is consistent with an

expansion through Tanzania to southern-central Africa. The data suggest

this dispersal was independent of the migration of Bantu-speaking peoples

along a similar route. Instead, the phylogeography and microsatellite

diversity of the E3b1f lineage correlate with the arrival of the

pastoralist economy in southern Africa. Our Y-chromosomal evidence

supports a demic diffusion model of pastoralism from eastern to southern

Africa ˜2,000 years ago.

Limited views of African cattle domestication often

fail to take into account the original genetic diversity of the African

species. This diversity may have been modified over time into a more

standardized type, but the indigenous domestication of the African breeds still

stands.

"Hanotte et al. used allele frequencies from 50 populations of modern cattle across the African continent to examine genetic variation. Their results reveal three ancient genetic signatures and each signature’s center of origin or region of entry. The native African taurine breed was independently domesticated in northeastern Africa, perhaps the eastern Sahara, and later migrated with pastoralist or crop-livestock farmers west and south. Asian zebu cattle were introduced along the east coast of Africa and in Madagascar and were most likely transported along a marine route from the Indian subcontinent. Finally, Near Eastern and European taurine cattle were primarily introduced along the shores of North Africa during the colonial period. These findings provide a genetic record of African cattle origins and migrations that have far-reaching implications for human migrations and the adaptive strategies used by African populations. They also require us to reexamine the models of domestication more broadly."

( M. A. Kennedy. The Origins of African Cattle. Current Anthropology Volume 44, Number 1, February 2003)

"Most (94%) modern cattle populations from

Northern Africa carry haplogroup T1, which is rarely found outside of

Africa (6% in the Near East and absent elsewhere). In contrast, modern

populations from mainland Europe carry 2 very similar haplogroups, T and

T3 (94%), which decrease in the Middle East (65%-74%) and almost

completely disappear in Africa (6%). Haplogroup T2 makes up the remainder

of this mtDNA diversity and is present at 6% in Europe and 21%-27% in the

Near East, but is absent from Africa. These haplogroup distributions have

been interpreted as indicating a Near East origin for European B. taurus

and the independent domestication of cattle in Africa (Bradley et al.

1996, Troy et al. 2001, Hanotte et al. 2002)... ancient DNA sequences

raise the possibility that the mtDNA gene pool for Northern African cattle

was more diverse ca. 900-2000 yr ago..

In conclusion, our results raise the possibility that the mtDNA gene pool for Northern African cattle ca. 900-2000 yr ago was more polymorphic in terms of the frequencies of the T1 and T/T3 haplogroups that currently predominate in African and European populations, respectively. This older polymorphism in Northern African cattle may reflect a transition from an even more diverse ancestral gene pool (as characteristic of its Near East progenitor) and/or the later secondary introduction of T/T3 haplotypes into this region by the immigration of European cattle

(Hanotte et al.2002, Bruford et al. 2003). Concomitantly, selective pressures from domestication and breeding efforts and/or genetic drift may have then led to the final homogenization of this older polymorphism into the current situation of essentially only the T1 haplogroup occurring in Northern Africa. These possibilities reemphasize the fact that both ancient and modern DNA data are of value in the ultimate resolution of the complex history of African cattle (Edwards et al. 2004)."

( Ascunce et al. 2007, An Unusual Pattern of Ancient Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups in Northern African Cattle.

Zoological Studies 46(1): 123-125.)

Keita and Boyce on peopling of the Nile Valley and

demic diffusion

From:

Keita and Boyce, Genetics, Egypt, And History: Interpreting

Geographical Patterns Of Y Chromosome

Variation,

History in Africa

32 (2005) 221-246

Ovacaprines appear in the western desert before the Nile valley proper

(Wendorf and Schild 2001). However, it is significant that ancient

Egyptian words for the major Near Eastern domesticates - Sheep, goat,

barley, and wheat - are not loans from either Semitic, Sumerian, or

Indo-European. This argues against a mass settler colonization (at

replacement levels) of the Nile valley from the Near East at this time.

This is in contrast with some words for domesticates in some early Semitic

languages, which are likely Sumerian loan words (Diakonoff 1981).. This

evidence indicates that northern Nile valley peoples apparently

incorporated the Near Eastern domesticates into a Nilotic foraging

subsistence tradition on their own terms (Wetterstrom 1993). There was

apparently no “Neolithic revolution” brought by settler colonization, but

a gradual process of neolithicization (Midant-Reynes 2000). (Also some of

those emigrating may have been carrying Haplotype V, descendents of

earlier migrants from the Nile valley, given the postulated “Mesolithic”

time of the M35 lineage emigration). It is more probable that the current

VII and VIII frequencies, greatest in northern Egypt, reflect in the main

(but not solely) movements during the Islamic period (Nebel et al. 2002),

when some deliberate settlement of Arab tribes was done in Africa, and the

effects of polygamy. There must also have been some impact of Near

Easterners who settled in the delta at various times in ancient Egypt

(Gardiner 1961). More recent movements, in the last two centuries, must

not be forgotten in this assessment.

“Archeological data, or the

absence of it, have been interpreted as suggesting a population hiatus in

the settlement of the Nile Valley between Epipaleolithic and the

Neolithic/predynastic, but this apparent lack could be due to material now

being covered over by the Nile (see Connor and Marks 1986, Midant-Reynes

2000, for a discussion). Analogous to events in the Atacama Desert in

Chile (Nunez et al. 2002), a moister more inhabitable eastern Sahara

gained more human population in the late Pleistocene-early Holocene

(Wendorf and Schild 1980, Hassan 1988, Wndorf and Schild 2001). If the

hiatus was real then perhaps many Nile populations became Saharan.

Later, stimulated by mid-Holocene droughts, migration from the

Sahara contributed population to the Nile Valley (Hassan 1988, Kobusiewicz

1992, Wendorf and Schild 1980, 2001); the predynastic of upper Egypt and

later Neolithic in lower Egypt show clear Saharan affinities. A striking

increase of pastoralists’ hearths are found in the Nile valley dating to

between 5000-4000 BCE (Hassan 1988). Saharan Nilo-Saharan speakers may

have been initial domesticators of African cattle found in the Sahara (see

Ehret 2000, Wendorf et. Al. 1987). Hence there was a Saharan “Neolithic”

with evidence for domesticated cattle before they appear in the Nile

valley (Wendorf et al. 2001). If modern data can be used, there is no

reason to think that the peoples drawn into the Sahara in the earlier

periods were likely to have been biologically or linguistically uniform.

…A dynamic diachronic interaction consisting of the fusion,

fissioning, and perhaps “extinction” of populations, with a decrease in

overall numbers as the environment eroded, can easily be envisioned in the

heterogenous landscape of the eastern Saharan expanse, with its oases and

Wadis, that formed a reticulated pattern of habitats. This fragile and

changing region with the Nile Valley in the early to mid-Holocene can be

further envisioned as holding a population whose subdivisions maintained

some distinctiveness, but did exchange genes. Groups would have been

distributed in settlements based on resources, but likely had contacts

based on artifact variation (Wendorf and Schild 2001). Similar pottery can

be found over extensive areas. Transhumance between the Nile valley and

the Sahara would have provided east-west contact, even before the later

migration largely emptied parts of the eastern Sahara.

Early speakers

of Nilo-Saharan and Afroasiatic apparently interacted based on the

evidence of loan words (Ehret, personal communication). Nilo-Saharan’s

current range is roughly congruent with the so-called Saharo-Sudanese or

Aqualithic culture associated with the less arid period (Wendorf and

Schild 1980), and therefore cannot be seen as intrusive. Its speakers are

found from the Nile to the Niger rivers in the Sahara and Sahel, and south

into Kenya. The eastern Sahara was likely a micro--evolutionary processor

and pump of populations, who may have developed various specific

sociocultural (and linguistic) identities, but were genealogically “mixed”

in terms of origins.

These identities may have further

crystallized on the Nile, or fused with those of resident populations that

were already differentiated. The genetic profile of the Nile Valley via

the fusion of the Saharans and the indigenous peoples were likely

established in the main long before the Middle

Kingdom…

…Hoffman (1982) noted cattle burials in Hierakonpolis,

the most important of predynastic upper Egyptian cities in the later

predynastic. This custom might reflect Nubian cultural impact, a common

cultural background, or the presence of Nubians.

There was some

cultural and economic bases for all levels of social intercourse, as well

as geographical proximity. There was some shared iconography in the

kingdoms that emerged in Nubia and upper Egypt around 3300 BCE (Williams

1986). Although disputed, there is evidence that Nubia may have even

militarily engaged upper Egypt before Dynasty I, and contributed

leadership in the unification of Egypt (Williams 1986). The point of

reviewing these data is to illustrate that evidence suggests a basis for

social interaction, and gene exchange.

There is a caveat for Lower

Egypt. If Neolithic/predynastic northern Egyptian populations were

characterized at one time by higher frequencies of VII and VIII (from Near

Eastern migration), then immigration from Saharan souces could have

brought more V and XI in the later northern Neolithic. It should further

be noted that the ancient Egyptians interpreted their unifying king,

Narmer (either the last of Dynasty 0, or the first Dynasty I), as having

been upper Egyptian and moving from south to north with victorious armies

(Gardiner 1961, Wilkinson 1999). However, this may only be the heraldic

“fixation” of an achieved political and cultural status quo (Hassan 1988),

with little or no actual troup/population movements. Nevertheless, it is

upper Egyptian (predynastic) culture that comes to dominate the country

and emerges as the basis of dynastic cilization. Northern graves over the

latter part of the predynastic do become like those in the south (see Bard

1994); some emigration to the north may have occurred - of people as well

as ideas.

Interestingly, there is evidence from skeletal biology

that upper Egypt in large towns at least, was possibly becoming more

diverse over time due to immigration from northerners, as the

sociocultural unity proceeded during the predynastic, at least in some

major centers (Keita 1992, 1996). This could indicate that the south had

been impacted by northerners with Haplotypes V, VII, and VIII, thus

altering southern populations with higher than now observed levels of IV

and XI, if the craniometric data indicate a general phenomenon, which is

not likely. The recoverable graves associated with major towns are not

likely reflective of the entire population. It is important to remember

that population growth in Egypt was ongoing, and any hypothesis must be

tempered with this consideration.

Dynasty I brought the political

conquest (and cultural extirpation?) of the A-Group Nubian kingdom Ta Seti

by (ca. 3000 BC) Egyptian Kings (Wilkinson 1999). Lower Nubia seems to

have become largely “depopulated,” based on archeological evidence, but

this more likely means that Nubians were partially bioculturally

assimilated into southern Egypt. Lower Nubia had a much smaller population

than Egypt, which is important to consider in writing of the historical

biology of the population. It is important to note that Ta Seti (of Ta

Sti, Ta Sety) was the name of the southernmost nome (district) of upper

Egypt recorded in later times (Gardiner 1961), which perhaps indicates

that the older Nubia was not forgotten/obliterated to historical memory.

Depending on how “Nubia” is conceptualized, the early kingdom

seems to have more or less become absorbed politically into Egypt. Egypt

continued activities in Nubia in later Dynasty I (Wilkinson 1999, Emery

1961).”

Linguist C. Ehret on why various theories of

demic diffusion from the Near East are flawed as to Africa

"Furthermore, the archaeology of northern Africa DOES NOT SUPPORT

demic diffusion of farming from the Near East. The evidence presented by

Wetterstrom indicates that early African farmers in the Fayum initially

INCORPORATED Near Eastern domesticates INTO an INDIGENOUS foraging

strategy, and only OVER TIME developed a dependence on horticulture.

This is inconsistent with in-migrating farming settlers, who would have

brought a more ABRUPT change in subsistence strategy. "The same

archaeological pattern occurs west of Egypt, where domestic animals and,

later, grains were GRADUALLY adopted after 8000 yr B.P. into the

established pre-agricultural Capsian culture, present across the

northern Sahara since 10,000 yr B.P. From this continuity, it has been

argued that the pre-food-production Capsian peoples spoke languages

ancestral to the Berber and/or Chadic branches of Afroasiatic, placing

the proto-Afroasiatic period distinctly before 10,000 yr B.P."

Source: The Origins of Afroasiatic

Christopher Ehret, S. O.

Y. Keita, Paul Newman;, and Peter Bellwood

Science 3 December 2004:

Vol. 306. no. 5702, p. 1680

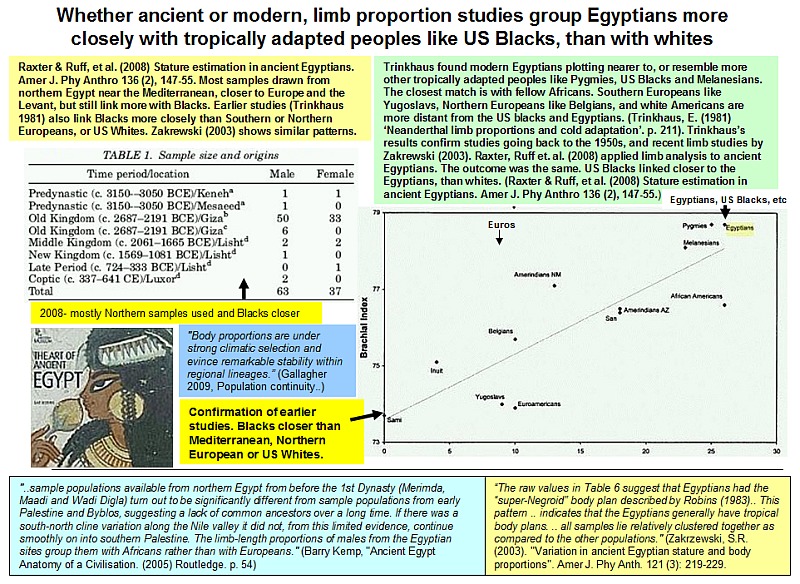

Movement and migration of peoples are sometimes related to

climate. Changing Saharan climate for example had an effect on the

movement of peoples in and out of Egypt. Tropically adapted peoples have

always been included in that movement, and show a continuity in the

population throughout Egyptian history.

|

![]()

![]()