Home | Quotations | Misc Notes | Notes 2 | Hair | DemicDiff |

Egypt in Africa | Black-Greek-DNA links| Misc news clips | Notes3| Notes 4| Ethiopians | Guestbook

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images | Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | DemicDiff |

Link to current African DNA research: (http://exploring-africa.blogspot.com/) pgf689 |

|

|

A survey of mainstream

academic sources

This document is free for

not-for-profit, personal and educational information use under

the

GNU Free Documentation License. It may not be used for commercial purposes.

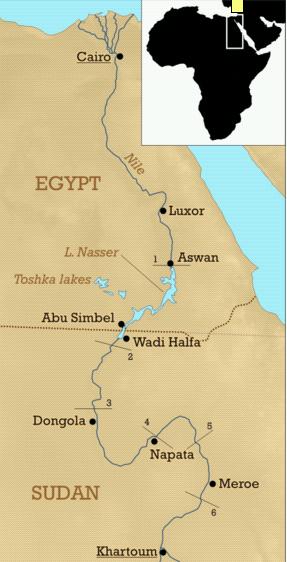

The Nile Valley is dominated by the longest river in the world, and is home to a large variety of peoples and cultures, who vary widely in skin color, facial shape and other indices. Below is a survey of the peopling and origins of various Nile Valley populations, including scholarly anthropological and archaeological views on their origins, similarities, differences, and related movements. A variety of factors are involved in studying the origins of the Nilotic or Nile Valley peoples, including geographic, genetic, and environmental data. Many contemporary mainstream anthropologists now take a more complex view of the Valley, placing Egypt in its African context as opposed to minimizing it, a common approach in past scholarship. A 1999 Physical Anthropology article in 'Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt' for example holds: [1]

-

"There is now a sufficient body of evidence from modern studies of skeletal remains to indicate that the ancient Egyptians, especially southern Egyptians, exhibited physical characteristics that are within the range of variation for ancient and modern indigenous peoples of the Sahara and tropical Africa.. In general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas." (Nancy C. Lovell, " Egyptians, physical anthropology of," in Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, ed. Kathryn A. Bard and Steven Blake Shubert, ( London and New York: Routledge, 1999) pp 328-332)

Much of modern Egyptology also reflects this placement of Egypt in the African context. As one archaeological text suggests, interpretations of the biological affinities and origins of the ancient Nile Valley peoples like the Egyptians:

"must be placed in the context of hypotheses informed by archaeological, linguistic, geographic and other data. In such contexts, the physical anthropological evidence indicates that early Nile Valley populations can be identified as part of an African lineage, but exhibiting local variation. This variation represents the short and long term effects of evolutionary forces, such as gene flow, genetic drift, and natural selection, influenced by culture and geography." ("Nancy C. Lovell, " Egyptians, physical anthropology of," in Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, ed. Kathryn A. Bard and Steven Blake Shubert, ( London and New York: Routledge, 1999). pp 328-332)[2]

Methodology is an important concern in the field. A number of research issues are shown below, along with a survey of populations in the Valley:

|

Issues in

skeletal and cranial |

Issues in DNA research |

|

|

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images | Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | DemicDiff |

Historical approaches to the complexity of the Nile Valley populations

Aryan models and Dynastic Race theories

Many mainstream references allude to the racial complexity of North Africa and the Nile Valley, going back to pre-dynastic times. These complexities do not yield easily to modern racial controversies or catch-all terminologies like "Mediterranean," or "Middle Eastern." Earlier histories of Egyptian people as recently as the 1970s classified them as Caucasoid or "Hamites" who migrated to the Nile Valley, transmitting light and civilization to slower-witted negro tribes. (Wyatt MacGaffey, 'Concepts of race in the historiography of northeast Africa', Journal of African History)[3]. This "Aryan" or "Hamitic" model is captured in scholar C. G. Seligman's influential "Races of Africa":

-

"Apart from relatively late Semitic influence . . . the civilizations of Africa are the civilizations of the Hamites, its history the record of these peoples and of their interaction with the two other African stocks, the Negro and the Bushman, whether this influence was exerted by highly civilized Egyptians or by such wider pastoralists as are represented at the present day by the Beja and Somali . . . The incoming Hamites were pastoral 'Europeans'--arriving wave after wave--better armed as well as quicker witted than the dark agricultural Negroes."[4]

Confusion, contradiction and exclusion in the theories of Egyptologists

A great deal of inconsistency and contradiction has also clouded the work of Egyptologists. As noted in one detailed 1967 study by archaeologists Berry and Ucko (Genetical Change in Ancient Egypt):

-

"This is attested by the tendency in the past (summarised by Chantre 1904) to postulate all sorts of improbable racial amalgams in Egypt: mixtures of peoples representing a singular variety of groups (viz. Libyan, Caucasian, Arab, Pelasgian, Negro, Bushman, Mongol, Hamitic, Hamito-Semitic- even Red Indian and Australian aboriginal) were alleged to have migrated into the Nile Valley." . Indeed Keith (1905:92) complained that the literature at that time included hopeless contradictions of three, six, one and two races."[5]

Later work was sometimes marked by the same pattern with even Cro-Magnons being thrown into the mix.[6] Berry and Ucko also note most Egyptologists in earlier years "are at pains to disclaim any Negro element in the Egyptian populations after the predynastic period except for the population of Sudanese Kerma.." while producing shifting definitions of exactly what 'negroid' was.

-

".. the basic weakness of all claims to distinguish or decry Negro elements on the basis of metrical analyses is the absence of any rigorous population comparisons to isolate particular featurers which can be described as negroid. It is typical of this unsatisfactory situation that F.P [Petrie] 1928:68) although basing himself entirely on the original Stoessiger report, could sumarise the Badarian skull material in terms which denied any serious Negro element."[7]

-

Disclaiming any hint of negroid presence, Petrie held that the ancient Egyptian skulls in question were of Indian origin, some thousands of miles distant, versus the surrounding area, or those further south, which were within a few hundred.[8]

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images | Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | DemicDiff | ImageGallery | Quotes | Rld | Nvbl | Fil |

Newer approaches: The Egyptians as simply another Nile Valley population

A number of current mainstream scholars such as Bruce Trigger, and Frank Yurco eschew a racial approach, asserting that the previous archaeological and anthropological approaches were 'marred by a confusion of race, language, and culture and by an accompanying racism'. [9] As to racial affinities of the people of northeast Africa, Yurco declares that all the peoples of the region are indigenous Africans and that arbitrary divisions into Negroid and Caucasoid stocks is misguided and misleading. To Yurco, the indigenous stocks are part of a continuum of physical variation in the Nile Valley. Just as Europeans are noted to vary between tall blonde Swedes, and shorter, darker Portuguese, or Basques with strikingly different blood types, so the Nile Valley populations are simply allowed similar variation. Other mainstream scholars such as Shomarka Keita applaud Trigger's and Yurco's approach but note the continued use of terms such as "Mediterranean" to incorporate the ancient Egyptians, and the continued use of classification schemes that screen out or deemphasize variability, and the rich diversity of the African people. As one mainstream anthropologist puts it:

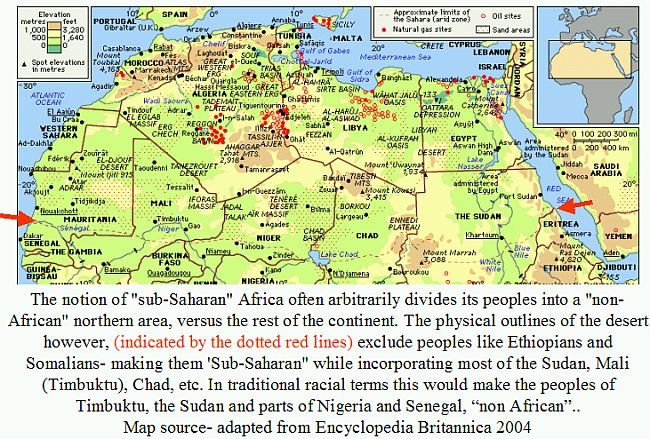

"The living peoples of the African continent are diverse in facial characteristics, stature, skin color, hair form, genetics, and other characteristics. No one set of characteristics is more African than another. Variability is also found in "sub-Saharan" Africa, to which the word "Africa" is sometimes erroneously restricted. There is a problem with definitions. Sometimes Africa is defined using cultural factors, like language, that exclude developments that clearly arose in Africa. For example, sometimes even the Horn of Africa (Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea) is excluded because of geography and language and the fact that some of its peoples have narrow noses and faces.

However, the Horn is at the same latitude as Nigeria, and its languages are African. The latitude of 15 degree passes through Timbuktu, surely in "sub-Saharan Africa," as well as Khartoum in Sudan; both are north of the Horn. Another false idea is that supra-Saharan and Saharan Africa were peopled after the emergence of "Europeans" or Near Easterners by populations coming from outside Africa. Hence, the ancient Egyptians in some writings have been de-Africanized. These ideas, which limit the definition of Africa and Africans, are rooted in racism and earlier, erroneous "scientific" approaches." (S. Keita, "The Diversity of Indigenous Africans," in Egypt in Africa, Theodore Clenko, Editor (1996), pp. 104-105. [10])

The general Egyptology consensus is captured in the words of mainstream scholar Frank Yurco:

-

"Certainly there was some foreign admixture [in Egypt], but basically a homogeneous African population had lived in the Nile Valley from ancient to modern times... [the] Badarian people, who developed the earliest Predynastic Egyptian culture, already exhibited the mix of North African and Sub-Saharan physical traits that have typified Egyptians ever since (Hassan 1985; Yurco 1989; Trigger 1978; Keita 1990.. et al.,)... The peoples of Egypt, the Sudan, and much of East African Ethiopia and Somalia are now generally regarded as a Nilotic continuity, with widely ranging physical features (complexions light to dark, various hair and craniofacial types) but with powerful common cultural traits, including cattle pastoralist traditions. (Trigger 1978; Bard, Snowden, this volume).(F. Yurco "An Egyptological Review," 1996)[11]

Egyptians cluster closer to other nearby African populations than to Europeans or Middle Easterners

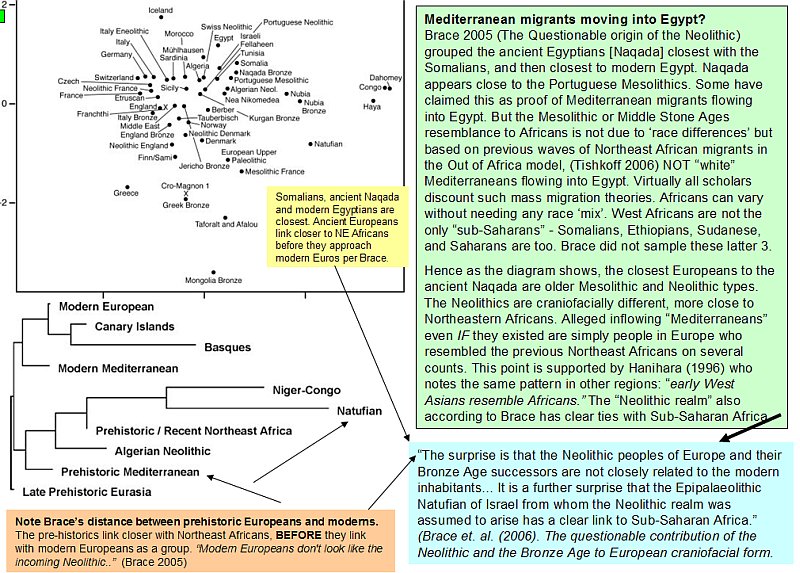

Several recent mainstream anthropology studies support the close relationship of the Nile valley peoples. This research rejects sensationalist theories that the ancients were of Indian, Australian, Greek, or Nordic stock, or nationalist theories that they are identical to Arabs, West African Bantu or Syrians. Instead they are most closely related to other Nile Valley and East African peoples- Somalis, northern Sudanics, and Ethiopians. This recent research confirms Frank Yurco's statement as to "one Nilotic continuity." For example, a 2005 study by Afrocentric critic C. Loring Brace groups ancient Egyptian populations like the Naqada closer to Nubians and Somalis than European, Mediterranean or Middle Eastern populations. (Brace, et al. 2005). [11a] Other craniometric studies confirm this finding. A 2003 study by Hanihara places the ancient Egyptians (Naqada/Gizeh) closer to Nubians (Kerma), and Somalians closer to other East African populations like Kenyans than to European or Middle eastern populations. (Hanihara 2003) Hanihara (1996) also shows that early West Asians (from what is today's "Middle East") resembled Africans.(Hanihara T., "Comparison of craniofacial features of major human groups," Am J Phys Anthropol. 1996 Mar;99(3):389-412.) [11b] .

Such studies are also consistent with metric analyses placing ancient Upper Egyptian populations like the Badari closer to populations in tropical Africa than to Mediterraneans, or Middle Easterners.[11c] Dental studies note the close relationship between ancient peoples of the Badari and Naqada cultures, and suggest that they continued on into the Dynastic period, with Egyptian samples being more closely related to North Africa than to Europe or the Middle East.[11d] DNA research on historical Nile Valley gene flow suggests close relationships and continuity between the Nubian and Egyptian populations, with greater south- north gene flow than north - south gene flow. (Krings 1999).[11e] This south-north movement is consistent with the hegemony of the south and its conquest or absorption of the north, ushering in the period of the Egyptian dynasties. Other studies confirm both Brace and Hanihara's findings:

"Overall, when the Egyptian crania are evaluated in a Near Eastern (Lachish) versus African (Kerma, Kebel Moya, Ashanti) context) the affinity is with the Africans. The Sudan and Palestine are the most appropriate comparative regions which would have 'donated' people, along with the Sahara and Maghreb. Archaeology validates looking to these regions for population flow (see Hassan 1988)... Egyptian groups showed less overall affinity to Palestinian and Byzantine remains than to other African series, especially Sudanese."[97a]

|

|

|

A 2005 study by Afrocentric critic C. Loring Brace groups ancient Egyptian populations like the Naqada closer to Nubians and Somalis than European, Mediterranean or Middle Eastern populations. Brace also shows that where Europeans appear to link with africans its OLDER Europeans that do so- Mesolithics, Neolithics etc. These looked like africans because they derived from the Out Of Africa Migration(s) and thus retained some tropical characteristics before becoming tropically adapted over time. Its a comparison of dark-skinned people looking like Africans living in Europe, to dark-skinned Africans in Africa itself. (Brace, et al. The questionable contribution of the Neolithic and the Bronze Age to European craniofacial form, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 January 3; 103(1): p. 242-247. An earlier 1993 study by Brace had placed Somalians closer to Upper Egyptian populations than to Europeans or Middle Easterners. Craniometric studies place ancient Upper Egyptian populations closer to populations in tropical Africa (the nearby Sudan) than to Mediterraneans, or Middle Easterners. (S.O.Y Keita, "Studies of Ancient Crania From Northern Africa," American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 83:35-48 (1990) |

|

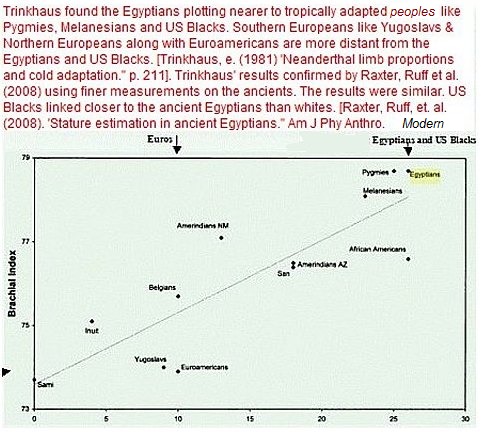

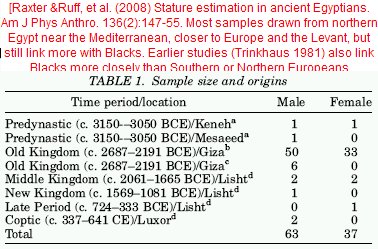

A 2003 study by Hanihara places the ancient Egyptians (Naqada/Gizeh) closer to Nubians (Kerma), and Somalians closer to other East African populations like Kenyans than to European or Eurasian (Middle Eastern) populations. (Tsunehiko Hanihara "Characterization of biological diversity..." (2003) Recent limb proportion studies find the ancient Egyptians

having "super negroid" body proportions, not

cold-adapted proportions like Europeans. (Zakrzewski,

S.R. (2003). "Variation in ancient Egyptian stature

and body proportions". American Journal of Physical

Anthropology 121 (3): 219-229.) Other similar studies

link the ancient Egyptians more closely with American

Blacks than Northern Europeans, and the same US Blacks closer to

Egyptians than Southern Europeans or

American Whites. (Raxter and Ruff, "Stature

estimation in ancient Egyptians," 2008) See

Trinkhaus (1981) for example, (Trinkhaus, E. (1981)

"Neanderthal limb proportions and cold

adaptation." p. 211) for comparisons to

Europeans. |

Some debates remain however as to the methodology used in classifying these ancient populations. These are addressed below.

Issues of methodology in skeletal, cranial and hair studies of ancient Nile Valley populations

General methodology issues

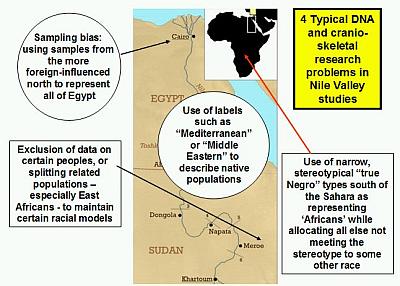

General methodological issues fall into five groups:

-

Inconsistent treatment of data on the Nile Valley peoples

-

Use of extreme types as "representative" of various peoples

-

Exclusion of data not meeting stereotypical ranges

-

Splitting of related populations

-

Labeling of populations in a manner that de-emphasizes their local context

Inconsistency. Some historians question why the same broad approach used with European populations is not also applied to Negroes who also show dolichocephaly, and also vary in other physical indices. They argue that a double standard is in play, and that the use of such terms as "Mediterranean" or "Middle Eastern" conveniently allow more skeletal remains from the Nile Valley to be essentially classified as Caucasoid, even incorporating Ethiopians, as in the Mediterranean race theories of Giuseppè Sergi. It is argued that the same line is drawn much more narrowly in defining "Negroid."[12] Variable human remains (such as the aquiline features of some Northeast African peoples, or the rounded foreheads of many African peoples) are thus assigned to Caucasoid groupings. These are interpreted as broadly and expansively as possible with a bearing on Egypt, covering the range of the Mediterranean zone from Portugal, to Morocco, to parts of Turkey. By contrast, the variation in "Negroids" is carefully defined in a much narrower sense as regards the Nile Valley. This inconsistent use of categories and definitions (broad Caucasian -- narrow Negro), it is held, downplays the Nilo-Saharan and Sudanic roots of the Egyptian gene pool. [13]

Use of stereotypical "true negro" types. Modern re-analyses of previous studies shows a clear tendency deny or minimize variability within the ancient Egyptian population.[14], As far as Negroid elements, this takes the form of establishing a baseline determination for a "true negro" (generally a sub-Saharan type) and anything not closely matching this extreme type is disregarded or incorporated into a Caucasoid or "Mediterranean" cluster. Conversely the same selective classification scheme is not applied to groups traditionally categorized as Caucasoid. Scholars such as Carelton Coons report "Mediterranean" remains that seem to have "Negroid" traits but do not mention the opposite, nor have scholars generally bothered to define a similarly stereotypical "true white."[15] According to one 2005 review:

-

"The assignment of skeletal racial origin is based principally upon stereotypical features found most frequently in the most geographically distant populations. While this is useful in some contexts (for example, sorting skeletal material of largely West African ancestry from skeletal material of largely Western European ancestry), it fails to identify populations that originate elsewhere and misrepresents fundamental patterns of human biological diversity."[16]

Exclusion of data not meeting stereotypical ranges. Older documentation shows researchers repeatedly excluding or minimizing certain skeletal remains in formulating approaches to the ancient Nile Valley people (See Berry and Ucko above) This pattern still occurs sometimes in contemporary analyses according to some scholars (Kittles and Keita 1997, Armelagos 2005, et. al. - see DNA section below). As regards older skeletal research for example:

-

"Nutter (1958), using the Penrose statistic, demonstrated that Nagada I and Badari crania, both regarded as Negroid, were almost identical and that these were most similar to the Negroid Nubian series from Kerma studied by Collett (1933). [Collett, not accepting variability, excluded "clear negro" crania found in the Kerma series from her analysis, as did Morant (1925), implying that they were foreign.].."[17]

-

Splitting of related Nile Valley groups. Some anthropologists maintain that these methods still continue with the use of more modern statistical aggregation techniques based on crania or on dental morphology. They include selective frontloading of measured indices to minimize variability, using the stereotypical "true" sub-Saharan type as a basis for comparison, separating out adjacent Nile Valley and Northeast African populations like Ethiopians and Somalians, and grouping all else not meeting the extreme sub-Saharan type into broad Caucasoid clusters, although such clustering may be given different names like "North African", "Middle Eastern" or "Southwest Asian". (The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence, S. O. Y. Keita, Rick A. Kittles, 1997)[18]

Lumping under Mediterranean clusters and labels. Re-analyses of scholarship show a clear tendency to lump remains under broad clusters or categories such as Mediterranean. Numerous studies of Egyptian crania have been undertaken, with many showing a range of types, and workers often describing substantial Negroid remains. Often this type has been lumped into a Caucasoid cluster, typically using the term "Mediterranean." A majority of these studies show the strong influence of Sudanic and Saharan elements in the predynastic populations and yet classification systems often incorporate them into the Mediterranean grouping. (Vercoutter J (1978) The Peopling of ancient Egypt)[19] According to one re-analysis of metric skeletal data on the ancient Nile Valley peoples (S.O.Y Keita, "Studies of Ancient Crania From Northern Africa,):

-

"Analyses of Egyptian crania are numerous. Vercoutter (1978) notes that ancient Egyptian crania have frequently all been "lumped (implicitly or explicitly) as Mediterranean, although Negroid remains are recorded in substantial numbers by many workers... The majority of the work describes a Negroid element, especially in the southern population and sometimes as predominating in the predynastic period (Falkenburger, 1947). Workers describing some tropical African morphological or morphometric affinities with southern predynastics and dynastics include Thompson and Randall-MacIver (1905), Thomson (19051, Giuffrida-Ruggeri (1915, 1916, Stoessiger (1927), Krogman (1937), Morant (1925,1935, 1937) (who described Upper and Lower Egyptian types without much emphasis on racial labeling), Nutter (19581, Strouhal (1968, 19711, and Angel (1972). Strouhal (1971) also analyzed hair in his study of 117 Badari crania, in which he concluded that >80% were Negroid; most of these were interpreted as being hybrids.."[20]

Hair studies. Kieta notes that while many scholars in the

field have used an extreme "true negro" definition for

African peoples, few have attempted to consistently apply the

same model in reverse and define a "true white." Such

an approach for example would define the straight hair in

Strouhal's hair sample as an exclusive Caucasian marker (10 out

of 49 or approximately 20%) and make the rest (wavy and curled)

hybrid or negro, at >80%. Strouhal's 1971 study itself

advances the most extreme definitions, claiming Nubians to be

white Europids overrun by later waves of Negroes, and that few

Negroes appeared in Egypt until the New Kingdom. (Eugen Strouhal,

Evidence of early penetration of negroes in Egypt", The

Journal of African History, Vol. 12, No. 1. (1971), pp. 1-9.)

Such claims have been thoroughly debunked by modern scholarship.

Attempts to define racial categories based on the ancient hair

rely heavily on extreme definitions, with "negroids"

typically being defined as narrowly as possible.

The use of hair in 'racial' analysis or race percentage

categories is rendered problematic by such skewed and

inconsistent models, and by other research in the area such as

the limb proportion studies of Zakrzewski, cranio-metric surveys

of Keita (2005) and Brace (2005), and the DNA research of Semino,

Keita et al. (See DNA section). The presence of other influences,

such as oxidation, bleaching, dyeing, Egyptian importing and

trading for hair from elsewhere to make wigs, pheomelanin

conditions allowing reddish hair in dark-haired populations, and

the Egyptian practice of burying hair separately from their

actual corpses also calls such methods into question. See the

analysis here for more on hair studies.

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images | Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | DemicDiff |

Issues of specific methodology and interpretation in Cranio-facial Anthropology

Cranial studies are used extensively in classifying and studying ancient Nile Valley population origins, relationships, and diversity. Methodological issues fall into four groups.

-

Inaccuracy in computer models used in analysis

-

Use of stereotypical models in splitting and grouping cranial data

-

Ignoring local variability within populations on such indices as nasal measurements

-

Skewed cranial databases that selectively exclude certain Nile Valley areas

Inaccuracy in computer models. The methodology used in statistical studies of skeletal data has also been challenged by some researchers, not only as to the manipulation of categories, but in the results obtained with computer programs such as Fordisc or CRANID commonly used by researchers to find matches between sets of data correlated with geographic origins or race. A test of one such program for example matched ancient Nubian samples with people as far afield as Hispanics, Japanese and Easter Islanders. Such programs and models critics hold, rely heavily on front-loading: starting with assumptions as to rigid, idealized 'true' types and thus misrepresenting fundamental patterns of human biological diversity. As one critical review of far-flung Nubian matches notes:

-

" If Fordisc 2.0 is revealing genetic admixture of Late Period Dynastic Egypt and Meroitic Nubia, then one must also consider these ancient Meroitic Nubians to be part of Hungarian, part Easter Islander, part Norse, and part Australian Aborigine, with smaller contributions from the Ainu, Teita, Zulu, Santa Cruz, Andaman Islands, Arikara, Ayatal, and Hokkaido populations. In fact, all human groups are essentially heterogeneous, including samples within Fordisc 2.0. Using Fst heritability tests, Relethford (1994) demonstrated that Howells’s cranial samples exhibit far more variation within than between skeletal series... This heterogeneity may also characterize the populations in the Forensic Data Bank.. (Frank l'engle Williams, Robert L. Belcher, and George J . Armelagos, "Forensic Misclassification of Ancient Nubian Crania: Implications for Assumptions about Human Variation," Current Anthropology, volume 46 (2005), pages 340-346)[21]

Use of stereotypical models in splitting and grouping cranial data. Use of 'true' types to split and organize data appears in several cranial studies. One such 1993 study found the ancient Egyptians to be more related to North African, Somalian, European, Nubian and, more remotely, Indian populations, than with Sub-Saharan Africans.[22]. Critics of this study hold that it achieves its results by manipulation of data clusters and analysis categories - casting a very wide net to achieve generic, general statistical similarities with populations such as Europeans and Indians. At the same time, the statistical net is cast much more narrowly in the case of 'blacks' - carefully defining them as an extreme type south of the Sahara and excluding related populations like Somalians, Nubians and Ethiopians,[23] as well as the ancient Badarians, a key indigenous group.[24]

It is held that when the data are looked at in toto without the clustering manipulation and selective exclusions above, then a more accurate and realistic picture emerges of African diversity. For example, ancient Egyptian matches with Indians and Europeans are generic in nature (due to the broad categories used for matching purposes with these populations) and are not due to gene flow, and that ancient Egyptians such as the Badarians show greater statistical affinities to tropical African types.[25]

Ignoring local variability within populations on such indices as nasal measurements. The variability of ancient Nile Valley populations in facial features calls several classification methods used in cranial and skeletal analysis into question. Narrow noses for example, appear among North American Plains Indians, as well as highland East Africans and Europeans. The racial categorizations of some scholars in past years thus allocated both Sioux warriors and Kenyan cattle herders to some sort of "Caucasoid" genetic mixture based on arbitrary definitions of this one trait as "European".[26] More objective recent scholarship however demonstrates that such noses are common in environments of cool, dry air- a routine climatic adaptation.[27] Such clinal factors do not rely on the need for race categories to explain how people look. Yet nose measurements and definitions based on 'true' racial models are still heavily used in some studies splitting Nile Valley peoples like Nubians, Somalians or Ethiopians into various 'racial' clusters.[28] As regards population diversity in Africa on this factor, one 1993 review notes that too often research using 'true' stereotypes:

-

"..presents all tropical Africans with narrower noses and faces as being related to or descended from external, ultimately non-African peoples. However, narrow-faced, narrow-nosed populations have long been resident in Saharo-tropical Africa... and their origin need not be sought elsewhere. These traits are also indigenous. The variability in tropical Africa is expectedly naturally high. Given their longstanding presence, narrow noses and faces cannot be deemed `non-African.'" [29]

Skewed cranial databases that selectively exclude certain Nile Valley areas. Exclusion of certain data can create a misleading picture of the ancient Nile Valley peoples. Such exclusions appear in standardized databases of cranial variation. Once such is the CRANID database, which uses samples from a single cemetery at Giza, in (northern) Lower Egypt dating around the final dynastic periods of Egypt (Dyn 26-30), to plot dendrograms suggesting that the population of ancient Egypt lies within a "European/Mediterranean bloc." In short the database is front-loaded towards a single cemetery close to the Mediterranean to serve as a "representative" standard in defining the ancient peoples. This skewed loading however, is not representative of the ancients as a whole, and excluded samples from the same time period based on several important cemetery sites at Elephantine, in Upper Egypt, further south. As respected mainstream Egyptologist Barry Kemp points out:

"If, on the other hand, CRANID had used one of the Elephantine populations of the same period, the geographic association would be much more with the African groups to the south. It is dangerous to take one set of skeletons and use them to characterize the population of the whole of Egypt." [30]

Population variability, limb proportions, and continuity Nile Valley peoples

As noted above, cranial and skeletal studies have several limitations, namely assumptions that 'racial' characteristics do not change from one generation to another and that statistical aggregation could represent huge populations when in essence the aggregation serves to hide or eliminate variability within those populations. (Encyclopedia Britannica, Macropedia, 2005 ed. Volume 18, "Evolution, Human", pp. 843-854)[31] Such studies however can still be valuable in analysis when the range of data is considered as a whole, without the selective exclusions and categorizations as noted above,[32] and when supported by other anthropological data such as material artifacts.[33] Balanced analyses of cranial and skeletal data show a range of population characteristics involved in those who peopled the Nile Valley. Some of this data is regional. One 1993 reanalysis for example, holds that:

-

"Analysis of crania is the traditional approach to assessing ancient population origins, relationships, and diversity. In studies based on anatomical traits and measurements of crania, similarities have been found between Nile Valley crania from 30,000, 20,000 and 12,000 years ago and various African remains from more recent times (see Thoma 1984; Brauer and Rimbach 1990; Angel and Kelley 1986; Keita 1993). Studies of crania from southern predynastic Egypt, from the formative period (4000-3100 B.C.), show them usually to be more similar to the crania of ancient Nubians, Kushites, Saharans, or modern groups from the Horn of Africa than to those of dynastic northern Egyptians or ancient or modern southern Europeans." [34]

Skeletal studies in the form of limb proportions have been also used to support the cranial data. Limb ratio studies of Trinkhaus (1981) plotted Egyptian datasets near tropical Africans, not Mediterranean Europeans, confirming observations almost a century old by Warren (1897). Robins and Shute (1983, 1986) evaluated predynastic and dynastic limb ratios finding strong correlation with Negroid datasets (super-negroid in their terminology). One study (Zakrzewski 2003) confirms older findings, showing that the ancient Egyptians possessed more tropical body proportions. This indicates that the Egyptian Nile Valley was not primarily settled by cold-adapted peoples, such as Europeans. As Zakrzewski notes in her findings:

-

"The raw values in Table 6 suggest that Egyptians had the “super-Negroid” body plan described by Robins (1983). The values for the brachial and crural indices show that the distal segments of each limb are longer relative to the proximal segments than in many “African” populations (data from Aiello and Dean, 1990). This pattern is supported by Figure 7 (a plot of population mean femoral and tibial lengths; data from Ruff, 1994), which indicates that the Egyptians generally have tropical body plans. Of the Egyptian samples, only the Badarian and Early Dynastic period populations have shorter tibiae than predicted from femoral length. Despite these differences, all samples lie relatively clustered together as compared to the other populations. (Zakrzewski, S.R. (2003). "Variation in ancient Egyptian stature and body proportions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 121 (3): 219-229.)[35]

Other limb proportion studies (Trinkhaus, E. 1981. "Neanderthal limb proportions and cold adaptation." p. 211) have compared Egyptians to southern Europeans, Northern Europeans, Euro-Americans and American Blacks, and found that the Egyptians compared more closely with American blacks than with either white group. Later studies, using finer measurements, ((Raxter, Ruff et. al. 2008, "Stature estimation in ancient Egyptians) found similar results for the ancient Egyptians, even when most of ancient Egyptian samples were drawn from Giza, close to the Mediterranean, an area likely to have more migration from white Middle Easterners or southern Europeans. Limb elements of these ancient samples were closer to that of modern US Negroes. Intralimb indices however, showed no significant differences between US blacks and Egyptians. Such links to Africoid or African peoples confirm earlier studies by Robins and Shute (1983) who called ancient samples 'super negroid' and Zakrzewski (2003), as to the affinities of the early Egyptians.

"Our results confirm that, although ancient Egyptians are closer in body proportion to modern American Blacks than they are to American Whites, proportions in Blacks and Egyptians are not identical.. Intralimb indices are not significantly different between Egyptians and American Blacks... brachial indices are definitely more ‘African’... There is no evidence for significant variation in proportions among temporal or social groupings; thus, the new formulae may be broadly applicable to ancient Egyptian remains." (Michelle Raxter, Christopher Ruff. et. al. "Stature estimation in ancient Egyptians", Am J Phys Anthropology, 2008, Jun;136(2):147-55)[35A]

Cranial analyses that include the broad range of populations in the Nile Valley tend to show a fuller picture of their diversity, as opposed to the use of one selective set of data. For example, when CRANID data is taken as a whole for the expanse of the Nile Valley, Egyptian, Nubian and African (Ethiopic) groups form a cluster together at some distance from others, and are closer to each other than to cranial data from the Near East, Turkey/Anatolia or Greece,[36] indicating confirmation with Egyptologist Frank Yurco's observation of the common heritage and continuity of the Nilotic peoples.[37]

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images | Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | DemicDiff |

Standards of interpretation: mixed versus variable populations

The issue of "mixed" populations

As regards mixed populations, the issues of methodology remain, particularly in view of the makeup or variability of ancient stocks in that region. To what group for example, will a mixed race individual be credited? Variability within individual groups also involves the question of arbitrary assignment. The "Negroid" grouping in the Saharan - Nilotic - Sudanic triangle has ranged from extremely short Pygmy tribes, to slender, seven-foot tall groups with aquiline features and wavy hair. Are the latter "Caucasoid" (as asserted in older histories), of "mixed" race, or simply just another variant within the Nile Valley or Northeast African populations? Similar variability occurs in European populations, with generally longer head shapes (dolichocephaly) seen in Scandinavian and Mediterranean populations, and shorter ones (brachycephaly) seen in central and eastern Europeans, along with clear distinctions on some DNA markers between these populations.[38] And yet it would be difficult to use such variation to biologically justify a rigid racial taxonomy for these European peoples, or to say that they were different races. They are generally seen as simply variants within a larger European population. In Northeast Africa however standards are applied differently according to some mainstream scholars.[39] Some older histories assert a "third race"[40]. A more specific reexamination of the early Nile Valley populations such as the Badari, show several affinities with a range of tropical African types. (S. Keita,'A brief review of studies and comments on ancient Egyptian biological relationships,' 1995)[41]

Difficulties with fossil remains and shifting terminology. Some researchers have moved away from the terms "Negroid" or "Caucasoid" in favor of formulations like "Saharan-Nilotic" or Africoid (see Trigger above and Keita below), which emphasizes the direct local area and indigenous populations in the Nile Valley. "Saharan-Nilotic" would include the Sudan, with its well established physical and cultural linkages with Nile Valley populations. Older formulations have included racial terminologies such as "Eastern Hamites" which basically substituted for "Caucasoid". Whatever the terms used, pinning down fossil evidence can be a problematic task. Samples classified as "Eastern Hamite" for example often have the narrow rounded forehead commonly typified as "Negroid".[42] Researchers in the past have also used the term "Mediterranean" for these "Negroid" samples, routinely reclassifying them as such.

Alternatives to notion of 'mixed populations. Some scholars such as Alan Templeton have challenged the notion of mixed populations (see DNA Analysis section below) holding that race as a biological concept is dubious and that only a minor percentage of human variability can be accounted for by distinct "races." They argue that modern DNA analysis presents a more accurate alternative, that of simply local population variants, gradations or continuums in human difference like skin color or facial shape or hair, rather than rigid categories. The notion of "mixed races" it is asserted, is built on the flawed assumptions of old racial models. [43] According to Templeton:

-

"Genetic surveys and the analyses of DNA haplotype trees show that human "races" are not distinct lineages, and that this is not due to recent admixture; human "races" are not and never were "pure." Instead, human evolution has been and is characterized by many locally differentiated populations coexisting at any given time, but with sufficient genetic contact to make all of humanity a single lineage sharing a common evolutionary fate.."(Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective, Alan R. Templeton. American Anthropologist, 1998)[44]

-

A number of other researchers hold that race may be relevant for certain modern medical diagnoses and treatments, and that it may be premature to completely disregard all population (or group) identifiers in biomedical research. Nevertheless they express caution about practices relying on assigning racial categories and identifiers.[45]

Population diversity and liknesses to non-African populations. Phenotypical similarities of African peoples to other peoples around the world are not surprising according to several mainstream researchers, because other populations derive from an initially diverse African source, spread over different time cycles. Cranio-metric studies (Hanihara 1996) confirm this holding, showing for example that early West Asians (today's 'Middle Easterner's) resembled Africans, and that elements like facial features draw from a common origin. Variations in how African peoples look are thus not necessarily a result of hybridization with another "race".[46a]

Distance analysis and factor analysis, based on Q-mode correlation coefficients, were applied to 23 craniofacial measurements in 1,802 recent and prehistoric crania from major geographical areas of the Old World. The major findings are as follows.. .. Recent Europeans align with East Asians, and early West Asians resemble Africans.. The craniofacial variations of major geographical groups are not necessarily consistent with their geographical distribution pattern. This may be a sign that the evolutionary divergence in craniofacial shape among recent populations of different geographical areas is of a highly limited degree. Taking all of these into account, a single origin for anatomically modern humans is the most parsimonious interpretation of the craniofacial variations presented in this study. (Hanihara T., "Comparison of craniofacial features of major human groups," Am J Phys Anthropol. 1996 Mar;99(3):389-412.) ;.[46a]

Other anthropologists also note that indigenous African variability is not surprising:

".. indicate that background genetic variation of Europeans, Oceanians, and Asians originated in Africa and precedes in time the presence of modern humans in these areas. Europeans and Asian-Australians did develop more unique genetic profiles over time, but had a common background before their average "uniqueness" emerged. This background is African in a bio-historical sense. Therefore, it should not be surprising that some Africans share similarities with non-Africans." (The Diversity of Indigenous Africans, S.O.Y. Keita, Egypt in Africa, (1996), pp. 104-105)

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images | Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | DemicDiff |

|Links1 | Link2

Population variants versus racial assignments: the Elongated Africans

The Elongated Africans. As regards local population variants, the entire East African and Nilotic zone shows substantial diversity within groups of peoples, and features automatically 'assigned' to a 'race' by various studies do not capture the complexity of real data on the ground.[47] Doubts about racial assignments appear even in older mainstream surveys. As regards aquiline noses for example, Hiernaux (1975)[48] presents archaeological evidence of such features among the most ancient East Africans (among the oldest homo sapien fossils discovered in East Africa) in the Gamble's Cave pre-historic site (Kenya) dating from 9,000 to 11,000 B.C.E. In short, one of the most ancient African populations in the general Nilotic area evolved narrow face and naso-facial patterns separately from and independent of any European or Asian genes, indicating that Africans are not 'special cases' but vary among themselves in how they look, just like other human populations. Hiernaux's findings are supported by Gabel (1961) and Rightmire (1975a,b). Such data also calls into question claims that Nilotic diversity is due to the migration of, or mix with outside Caucasoids or Asiatics.[49]

-

".. all their features can be found in several living populations of East Africa, like the Tutsi of Rwanda and Burundi, who are very dark skinned and differ greatly from Europeans in a number of body proportions.. There is every reason to believe that they are ancestral to the living 'Elongated East Africans'. Neither of these populations, fossil and modern, should be considered to be closely related to the populations of Europe and western Asia...(Hiernaux) "

DNA analysis on the key E3b Y-chromosone haplogroup (Cruciani et al, 2004) show that it is the primary genotype of both Elongated and Broad Africans. East Africans for example, who carry E3b don't cluster with Europeans, or Middle Easterners and E3b carrying East Africans such as the Oromo and Borana have little to no European specific Haplotypes. E3b originated in sub-Saharan Africa, is largely confined there and is rare outside Africa. (Fulvio Cruciani, et. al. "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa," Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74:1014-1022, 2004) 50a

Genetic variation part of a built-in native baseline, affected by recent gene flow, but still part of indigenous diversity. Modern generic studies demonstrate that simple race mix models used historically in the field- that of migrating Hamites or Eurasians substantially replacing or diluting the basic stock of peoples like Ethiopians or Somalis are simplistic. Rather they indicate Africa as the "home base" of genetic diversity, with numerous mutations and variants flowing into other parts of the continent, then out to other parts of the globe. Backflow introduced additional mutations in African stocks, but did not replace their essential indigenous character, which was very diverse to begin with. Thus various peoples like Ethiopians or Somalians, who differ from West African Bantu speakers on some genetic markers are part of one continuum of native diversity, indigenous variants that in turn absorbed more recent gene flow form outside Africa (the recent Arab expansion era for example), and are not necessarily a "mix" with invading white Hamites or migrants, as postulated under various Hamitic or demic diffusion theories. As noted by Tishkoff (2000):

"The fact that the Ethiopians and Somalis have a subset of the sub-Saharan African haplotype diversity and that the non- African populations have a subset of the diversity present in Ethiopians and Somalis makes simple-admixture models less likely; rather, these observations support the hypothesis proposed by other nuclear-genetic studies (Tishkoff et al. 1996a, 1998a, 1998b; Kidd et al. 1998) that populations in northeastern Africa may have diverged from those in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa early in the history of modern African populations and that a subset of this northeastern-African population migrated out of Africa and populated the rest of the globe. These conclusions are supported by recent mtDNA analysis (Quintana-Murci et al. 1999)." [Tishkoff et al. (2000) Short Tandem-Repeat Polymorphism/Alu Haplotype Variation at the PLAT Locus: Implications for Modern Human Origins. Am J Hum Genet; 67:901-925];50b

Some theories attempt to link peoples like the Ethiopian Falashas (Black Jews) with part of a racial mix involving outside Middle Easterners, but modern genetics again points to built in native diversity that accounts for genetic differences between the Falashas and other African populations rather than a mix with outside migrants. One study by Cruciani, Shen et al. illustrates this:

These data, together with those reported elsewhere (Ritte et al. 1993a, 1993b; Hammer et al. 2000) suggest that the Ethiopian Jews acquired their religion without substantial genetic admixture from Middle Eastern peoples and that they can be considered an ethnic group with essentially a continental African genetic composition. (Am J Hum Genet. 2002 May; 70(5): 1197-1214, "A Back Migration from Asia to Sub-Saharan Africa Is Supported by High- Resolution Analysis of Human Y-Chromosome Haplotypes," Fulvio Cruciani,1 Piero Santolamazza,1 Peidong Shen, et. al)

Demic diffusionism and incoming non-African race models. A number of demic diffusion theories posit the replacement or absorbtion of native African stocks by incoming Asiatic migrants, as indicated by the spread of the Afro-Asiatic language and such elements as agriculture in Africa. While there certainly has been two-way migration between the Near East and Africa, neither the genetic nor the linguistic evidence support a sweeping demic diffusion model, nor the claimed racial percentage allocations as a result of such diffusion (i.e. the 'Hamitic Hypothesis' or 'Dynastic Race' theories). None of the African languages like Berber or ancient Egyptian are branches of Semitic, Indo-European or Sumerian. African words for Near Eastern domesticates like barley or sheep are not Semitic loan words, even though a number of such domesticates appeared first in the Near East.

Y-genetic profiles of the peoples of Ethiopia etc are different from core Semitic groups. "The Y genetic profiles of the Horn–Nile Valley region are different from those of the core Semitic-speaking populations in the Near East, who are characterized by a high frequency of M89 variants in the J and R haplogroups. (But as previously noted, the M35 lineage was taken into the Near East before the Neolithic perhaps by pre-proto-Semitic speakers)." Keita (2004)

A number of other writers have attempted to apply race mix models to northern Egypt which is closer to Libya and the Mediterranean, by characterizing the northern Egyptians as primarily Berber hybrids. This race model approach seriously underweighs and ignores the genetic diversity of the ancient peoples according to one 2004 critique:

-

"It is important to say that the indigenous northern Egyptians, while adjacent to the Libyco- Berber region, cannot simply be called ‘‘Berbers.’’ The Y chromosome data suggest that the original Egyptian Nile Valley population cannot be treated analytically as ‘‘Berber,’’ thereby in effect negating the distinctiveness and identity of the core indigenous ancient Nile Valley populations (see, e.g., Harich et al., 2002; Luis et al., 2004; Herrera et al., 2004, for a description of ‘‘Egyptians’’ as merely being an ‘‘Arab’’–‘‘Berber’’ admixture/composite, without a discussion of the indigenous Nile Valley population).

Some Horn populations assimilated southwest Asians, and even adopted their languages, which likely began as lingua francas. Certain Ethiopian groups evince substantial frequencies of ‘‘Near Eastern’’ genes (Y chromosome J group lineages), likely due to the assimilation of migrants after the first millennium BC(Munro-Hay, 1991),with some founder effect, but this is not substantially true for Oromo and Somali peoples (see, e.g., Comas et al., 1999; Sistonen et al., 1987). Linguistic evidence does not suggest that Semitic speakers brought agriculture to Ethiopia. (The Ethiopian genetic profile may have valid alternative explanations incorporating bi-directional migrations and settlements of great antiquity, depending on how old linguistics would predict the ancestral Ethio-Semitic language to be, in order to account for the present linguistic variation.) Ancient gene flow from such migrations would have been reworked by the new environment and demographic factors, and thus become a part of African biological history.It is important to say that there is no evidence to suggest that in the Holocene population replacement occurred in any of these regions as a whole based on the Y chromosome data. Populations should be viewed processually as dynamic entities over time and not ‘‘static’’ entities. The presence of M35/215 lineages and the Benin sickle cell variant in southern Europe illustrates this well. [S. Keita "Exploring Northeast African Metric Craniofacial Variation at the Individual Level: A Comparative Study Using Principal Components Analysis," AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HUMAN BIOLOGY 16:679–689 (2004)]50c

Many of these criticisms of demic diffusion as applied to the African environment are also reflected in many applications to European peoples. See general critique of demic diffusion here from Europe's First Farmers, by Theron Douglas Price, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 60- 72. Instead of massive replacements or colonizations, other scholars indicate an availability model based on small scale contacts and trade. These weaknesses in the European model are even more pronounced where Africa is concerned. Natural give and take and exchange between human groups of different regions is not unusual. Whether this translates into incoming groups of cattle bearing Caucasoids achieving genetic or 'racial' preponderance over native African peoples is problematic. Such is postulated under various race percentage models. Recent DNA data (Bradley et al. 1996, Troy et al. 2001, Hanotte et al. 2002) however, shows that far from waiting for reputed European or Near Eastern colonists or migrants to introduce things like cattle herding, ancient African peoples had already independently domesticated native cattle breeds centuries before alleged Caucasoid colonization. Agriculture was already well underway in the Nile Valley, and other parts of Africa before alleged Caucasoid settlers arrived. In terms of population stocks, DNA, cranio-metric, dental and limb proportion studies indicate long-term continuity of ancient stocks that left them fundamentally intact, not sweeping replacement and colonization.

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images | Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | DemicDiff |

Modern DNA analysis used on ancient Nile Valley peoples

The high genetic diversity of the East African peoples and the PN2 bridge

High genetic diversity of African peoples. The DNA research of Tishkoff and Williams (2002), et. al. (Tishkoff SA, Williams SM. "Genetic analysis of African populations..") notes that Africa, particularly East Africa, is home to the highest levels of genetic diversity in the world, and that "all non-African lineages can be derived from a single ancestral African haplogroup... non-African populations [harbour] only a subset of genetic diversity present in Africa as would be expected.." in the out of Africa evolutionary model. DNA surveys of 33 globally diverse populations, found that all non-African populations have a similar pattern of haplotypic variability and a subset of variability seen in Ethiopian and Somalian populations, "which is itself, a subset of the variability that is present in other sub-Saharan populations."

Tishkoff and Williams suggest that a subset of the ancient northeast African population played a large role in populating the rest of the globe. "Analysis of mtDNA and Y-chromosone diversity supports a single East African source of migration out of Africa." According to the study:

-

"Population history in Africa is likely to be a complex web of population diversification that involves population expansions, contractions, fragmentation, and differential levels and patterns of gene flow. An analysis of genome-wide genetic variation in diverse African populations is required to understand better the genetic structure of these populations."[50]

"Africa contains tremendous cultural, linguistic and genetic diversity, and has more than 2,000 distinct ethnic groups and languages.. Studies using mitochondrial (mt)DNA and nuclear DNA markers consistently indicate that Africa is the most genetically diverse region of the world. However, most studies report only a few markers in divergent African populations, which makes it difficult to draw general conclusions about the levels and patterns of genetic diversity in these populations. Historically, human population genetic studies have relied on one or two African populations as being representative of African diversity, but recent studies show extensive genetic variation among even geographically close African populations, which indicates that there is not a single ‘representative’ African population." (Tishkoff SA, Williams SM., Genetic analysis of African populations: human evolution and complex disease. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002 Aug (8):611-21.)[50]

"Representative Africans and backflow theories." Some theories speculate that Y- genetic elements associated with the Haplogroup "E" originally beginning in Africa, flowed out from that source and mutated into other sub-clades such as E-M34 chromosomes. These mutations in turn flowed back into Africa. (Cruciani 2004).50a While gene flow of varying proportions is nothing unusual in the history North and Northeastern Africa, attempts to assign Near Eastern or Mediterranean "racial" categories to the peoples of the region on this basis are problematic.

The original Y-chromone marker "root stock" is of African origin, reflecting its beginning base of vast African genetic diversity. Any backflow mutations may simply reflect the built-in diversity inherent in the original root stock which is based in sub-Saharan Africa, not north or Northeast Africa. Haplogroup E is far more diverse in sub-Saharan east Africa than it is in northeast Africa. The ancestors to outside mutations from the Near East and elsewhere, the ancestral YAP+ clades, gave rise to such mutations as haplogroup "D". Other mutations such as E -M34 are dependent on another African ancestor, the undifferentiated E-M35 chromosomes, which are essentially confined to sub-Saharan Africa.

Undifferentiated PN2* chromosomes, the ancestral clade needed to give rise to downstream E clades like E1a1a (E3a) and E1a1b (E3b) are rare to non-existent in northeast Africa, and the ancestral YAP+ clades which would be essential to giving rise to haplogroups E and D, are virtually non-existent outside of Africa. (Keita 2004).[51a] In short, backflow mutations are based on African diversity, need ancestor triggers based in sub-Saharan Africa, and are themselves another subset of original sub-Saharan baseline variability, the engine that gave rise to all these variants.

Such complexity calls into question attempts to slice up ancient East and Northeast African populations into assigned proportions or percentages of Negroid, Caucasoid, Asiatic, or Middle Eastern race groups. It also calls into question attempts to assign such populations to one monolithic type. Nilo-Saharan and Bantu speakers for example differ in some respects, but both strands are indigenous Africans. And despite their wide dispersion, Bantu speakers cannot be considered to be "representative" of "true" Africans. They are simply one more variant in the mix and groupings of African genetic diversity. Per Tishkoff (2002) "there is not a single ‘representative’ African population."

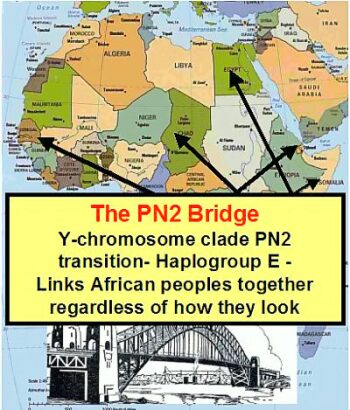

The PN2 Transition

Kittles and Keita (2004) also note the vast genetic diversity of Africans, and how similar looking people may not possess the same DNA pattern. A DNA lineage may also include people who do not look the same outwardly.[51]

"Individuals with the same morphology do not necessarily cluster with each other by lineage, and a given lineage does not include only individuals with the same trait complex (or 'racial type'). Y-chromosome DNA from Africa alone suffices to make this point. Africa contains populations whose members have a range of external phenotypes. This variation has usually been described in terms of 'race' (Caucasoids, Pygmoids, Congoids, Khoisanoids). But the Y-chromosome clade defined by the PN2 transition (PN2/M35, PN2/M2) shatters the boundaries of phenotypically defined races and true breeding populations across a great geographical expanse. African peoples with a range of skin colors, hair forms and physiognomies have substantial percentages of males whose Y chromosomes form closely related clades with each other, but not with others who are phenotypically similar. The individuals in the morphologically or geographically defined 'races' are not characterized by 'private' distinct lineages restricted to each of them." (S O Y Keita, R A Kittles, et al. "Conceptualizing human variation," Nature Genetics 36, S17 - S20 (2004)

The PN2 transition thus unites a large number of African peoples,

independently of how the look. Narrow noses or loosely curled

hair for example do not automatically indicate "Caucasoid

admixture" but are simply another routine variant within the

African genetic spectrum. Likewise, dark skin or tightly curled

hair do not necessarily indicate "Bantu migrations" to

assorted regions of Africa. As noted in one 2004 mainstream

analysis:

-

"A review of the recent literature indicates that there are male lineage ties between African peoples who have been traditionally labeled as being ‘‘racially’’ different, with ‘‘racially’’ implying an ontologically deep divide. The PN2 transition, a Y chromosome marker, defines a lineage (within the YAPþ derived haplogroup E or III) that emerged in Africa probably before the last glacial maximum, but after the migration of modern humans from Africa (see Semino et al., 2004). This mutation forms a clade that has two daughter subclades (defined by the biallelic markers M35/215 (or 215/M35) and M2) that unites numerous phenotypically variant African populations from the supra-Saharan, Saharan, and sub-Saharan regions based on current data (Underhill, 2001).

The M2 lineage is mainly found primarily in ‘‘eastern,’’ ‘‘sub-Saharan,’’ and sub-equatorial African groups, those with the highest frequency of the ‘‘Broad’’ trend physiognomy, but found also in notable frequencies in Nubia and Upper Egypt, as indicated by the RFLP TaqI 49a, f variant IV (see Lucotte and Mercier, 2003; Al-Zahery et al. 2003 for equivalences of markers), which is affiliated with it. The distribution of these markers in other parts of Africa has usually been explained by the ‘‘Bantu migrations,’’ but their presence in the Nile Valley in non- Bantu speakers cannot be explained in this way. Their existence is better explained by their being present in populations of the early Holocene Sahara, who in part went on to people the Nile Valley in the mid-Holocene, according to Hassan (1988); this occurred long before the ‘‘Bantu migrations,’’ which also do not explain the high frequency of M2 in Senegal, since there are no Bantu speakers there either." [S. Keita, "Exploring Northeast African Metric Craniofacial Variation at the Individual Level: A Comparative Study Using Principal Components Analysis," AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HUMAN BIOLOGY 16:679–689 (2004)][51a] ontents | History |

Cranio-skeletal research

|

Mixed pop |

DNA methods |

DNA research problems |

Sahara - Sudan- Levant |

Continuity |

Languages |

Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara |

Visual images |

Summary | Misc Notes |

Hair |

DemicDiff |

ImageGallery

| Quotes

|

Rld |

Nvbl |

Fil |

DNA data showing linkages between Nile Valley and other African populations

DNA studies on modern Nile Valley populations. While the high genetic diversity of nearby East African populations impacted the Nile Valley, a more specific 2004 mtDNA study of upper Egyptians from Gurna performed found a genetic ancestral heritage to modern East Africans, characterized by a high M1 haplotype frequency, and another study links Egyptians in general with people from modern Eritrea and Ethiopia.[52]

A 2003 Y chromosome study was performed by Lucotte on modern Egyptians, with haplotypes V, XI, and IV being most common. Haplotype V is common in Berbers and Ethiopian Falashas (black Jews) has a low frequency outside Africa. Haplotypes V, XI, and IV are all supra/sub-Saharan horn of Africa haplotypes, and they are far more dominant in Egyptians than in Near Eastern or European groups.[53]

DNA studies of autosomal short tandem repeat loci (STRs) in modern Egyptian populations, where they are not lumped with other regions, such as Libya, suggest important genetic differences between Egyptian and European populations (Klintschar et al. 1999).[54], and the work of such scholars as Tishkoff 2002 showing that the highest incidence of genetic diversity is found in East Africans, caution against simple racial percentage models. The DNA data is also supported by the metric work on skeletal remains,[55], (see "Summary" section below) and numerous cultural and material linkages between Nile Valley peoples demonstrated by other scholars (see also Cultural Linkages section below).

DNA studies on ancient mummies. DNA samples on ancient remains can be difficult to process due to contamination by fungi and a host of other factors.[56] However when ancient samples are analyzed they yield a picture suggesting the primarily indigenous nature of many Nile Valley peoples. For example, when ancient mitochondrial DNA was tested from a liver found in a canopic jar belonging to Nekht-Ankh, a Middle Kingdom priest, they were found to be quite similar to modern Egyptian mitochondrial lineages. Results from further DNA comparisons to non-southern Nile Delta populations in the late 1980s found that "small subsets of modern Egyptian mitochondrial DNA lineages are closely related to Sub-Saharan African lineages."[57]

DNA studies of Nile Valley gene flow. A 1999 DNA study of gene flow among the Nile Valley populations raises even more doubts about the Aryan model's claims of a "Mediterranean race" sweeping into the north, then branching out to civilize the darker natives further south. The study assessed the extent to which the Nile River Valley has been a corridor for human migrations between Egypt and sub-Saharan Africa. Overall the the gene flow suggests a north-south axis of distribution with the genetic mix between Nubia and Egypt consistent with historical evidence for long-term interactions between Egypt and Nubia. The study suggests greater weight of gene flow from the 'darker' south to the north, than from north to south.[58]

This finding is also consistent with a 2004 mtDNA study of Upper Egyptians at Gurna, a population with an ancient cultural history, that found genetic linkages extending back into older ancestral East African populations particularly Ethiopia.[59] The significance of south-north movement or connections is also reflected in ancient Egyptian origin myths, that maintained their ancestors derived from East Africa, such as the region of Punt, around modern day Somalia (Cottrell 1961, Davidson 1959).[60] A greater weight of southern movement is also reflected in the region's more advanced pre-dynastic material culture, and eventual conquest or absorption of the north by the south (Bard 1987). The later coming of other peoples to the Nile Valley (Hyskos, Assyrians, etc) would alter its gene flow even more, and the role of some rulers of southern origin (i.e. Menthuhotep, et al.) as restorationists or unifiers in Egyptian history against such outsiders is well known.[61] Nevertheless, the preponderance of most mainstream research in both DNA and skeletal measures suggests long term indigenous population continuity of the Nile Valley peoples.[62]

DNA and linkages between Nile Valley and Levantine/Middle Eastern populations

Some DNA research demonstrates genetic linkages between the

peoples of the Near East (Iran, Iraq, etc) with those of the Nile

Valley and adjoining areas. Such linkages are not unusual given

the movements of peoples. (Krings et al.). One such study

researched Somalis, and holds that East Africans are more related

to Eurasians than sub-Saharan Africans by a 10% margin.[62a]

However the same study also shows that East Africans (Somalians,

Oromos of Ethiopia and North Kenya, etc) are linked with each

other to a much higher extent than the 10% differential influence

between Eurasians or sub-Saharan Africans, (15% and 5%

respectively). Ironically, the study's use of such labels as

"sub-Saharan" is misleading, since both Somalians and

Kenyans are located below the Sahara. Other research on Egyptian

populations also show the same pattern, with stronger links to

other localized East African populations than European,

sub-Saharan or Middle Eastern groups.[62b]

Other scholars show that Egyptians fit comfortable within the range of black Sub-Saharan peoples from Eritrea/Ethiopia such as the Tigre people.[62c]

Other research illustrates that modern Egyptians have greater

genetic affinities primarily with populations of North and

Northeast Africa than with Europeans, sub-Saharan Africans or

Arabs.[62d] It

should be noted that the peoples of the Horn of Africa, who are

closely related to Egyptians, are "sub- Saharan",

whether defined as such by the oft used 15-degrees latitude line,, or by the PN2 Y-Genetic transition, that links a vast

number of African peoples together, even though they look

different outwardly.(S. Keita, History in Africa, Vol. 20,

(1993), 129-154).[62e]

Such diverse population patterns show a mix of genetic strands

that cannot be defined in stark racial terms as of a narrowly

stereotyped "sub-Saharan" type, versus all others. The

"sub-Saharan" component is itself highly variable, with

types such as "elongated" (some East African types) or

"broad" African (some West African types), or any

number of variants with differing body type, skin color, etc. As

one anthropologist puts it: "The extreme Negroid

variant is just that, a variant, and not a "founding"

or the "original" type." (S. Keita, History in Africa, Vol. 20, (1993), 129-154).[62e]

This variability is reflected in DNA data as well. Thus various

gene mutations found near Africa, such as that in the Middle

East, are a subset of the original baselines found in Africa

before out-migration. This baseline is the most diverse in the

world. Cranio-metric studies reflect this reality. Hanihara

(1996) for example found early West Asians to resemble Africans,

confirming the point of origin in the baseline stock. As

researcher Cavalli-Sforza notes about gene variations in

Africans:

-

" In other words, all non-Africans carry M168. Of course, Africans carrying the M168 mutation today are the descendants of the African subpopulation from which the migrants originated.... Thus, the Australian/Eurasian Adam (the ancestor of all non-Africans) was an East African Man." (Linda Stone, Paul F. Lurquin, L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Genes, Culture, and Human Evolution: A Synthesis, Wiley-Blackwell: 2006, pg 108)

Gene flow from outside Africa into this already diverse stew

does not define away its essential Africanity. One study for

example, notes gene flow between Yemen and Ethiopia as a two-way

process over the span of history, affected by many factors-

ranging from the Bantu speaking dispersals, the slave trade or

migration and trade. It also notes however that "The

sub-Saharan African component of Ethiopians has remained

untouched by such influences and may therefore be considered most

representative of the indigenous gene pool of sub-Saharan East

Africa."[62f]

Ethiopian gene flow into Yemen did not make the Yemenis another

race, neither did gene flow into Ethiopia make the native peoples

cease being Ethiopian. Scholars such as Egyptologist Frank Yurco

(1996) also affirms this basic continuity of peoples: "Certainly

there was some foreign admixture [in Egypt], but basically a

homogeneous African population had lived in the Nile Valley from

ancient to modern times... [the] Badarian people, who developed

the earliest Predynastic Egyptian culture, already exhibited the

mix of North African and Sub-Saharan physical traits that have

typified Egyptians ever since (Hassan 1985; Yurco 1989; Trigger

1978; Keita 1990")" [62g]

Contents | History | Cranio-skeletal research | Mixed pop | DNA methods | DNA research problems | Sahara - Sudan- Levant | Continuity | Languages | Cultural linkages- Nubia-Egypt-Sahara | Visual images |

Summary | Misc Notes | Hair | Geographic | DemicDiff |

Methodological problems in applying of DNA analysis to ancient Nile Valley populations

When attempts are made to split the ancient Nile Valley populations along racial lines using DNA analysis, the following methodological problems have been noted by several scholars. (Keita and Kittles 1997, Boyce and Keita 2005, Liberman 2001 et. al.)

-

'Race' as a factor in differentiating human populations occurs in very low proportions calling into question its usefulness re Nile Valley peoples

-

Use of stereotypical "true" negro types to represent African genetic diversity

-

Contradictory results from DNA racial studies

-

Use of limited samples as "representative" of "Africans" versus use of broad data ranges to represent Europeanized populations

-

Pre-sorting and lumping of samples into racial categories before beginning DNA analysis thus skewing final results

-

Limited applicability of DNA racial analysis in dicing up closely related population

-

Exclusion of African data that does not meet pre-determined racial models

-

Use of misleading labeling such as "Oriental" or "Near Eastern" rather than taking DNA data in local context

-

Sampling bias- commonly using samples from northern Egypt, which as had more foreign influx from the Mediterranean and Near East as 'representative' of all Egyptians

-

Inconsistent methodology and failure to look at broader more complex models of population genesis

Some DNA analysis throws doubt on racial categories

Modern DNA analysis such as the work of Luigi Cavalli-Sforza, has analzed genetic affinities among peoples and enabled broad clustering groups to be defined. These clusters are held to relate fairly well to the "classical" racial groupings.[63] Other researchers however such as Lewontin using the same analysis point out that the genetic affinities attributable to race only make up 6-10% of variant analysis. This is a threshold well below that used to analyze lineages in other species, leading many researches to question the validity of race as a biological construct. (Apportionment of Racial Diversity: A Review, Ryan A. Brown and George J. Armelagos, 2001, Evolutionary Anthropology, 10:34-40)[64] Lewontin's analysis has been validated and replicated by numerous other studies, using a wide range of different analytical methods- (Latter 1980, Nei and Roychoudhury 1982, Ryaman 1983, Dean 1994, Barbujani 1997).

Other similar work using mtDNA analysis shows a larger variance within designated racial categories than outside (Excoffier 1992). Work such as Miller (1997) has found greater racial difference by focusing on specific loci, but these are compartively rare (2 out of 17, and 4 out of 109 in re-analyses by other researchers), and are well within the range of other factors such as genetic drift and clinal variation. Restudies of loci data (Lewotin, Barbajuni, Latter, et. al as noted above)yield even more conservative estimates of race as a factor in genetic variability.[65] On the basis of this data, some scholars (Owens and King 1999) hold that skin color, hair and facial features and other factors are more attributable to climate selective factors rather than stereotypic racial differences.[66]

DNA racial studies and contradictory results from study design

Liberman and Jackson (1995), and Ryan and Armelagos(2001) point to contradictory results in DNA racial analysis, in that many studies "select the small proportion of genetic variability that is roughly apportionable by race to plot out dendrograms of essentially false categorizations of human variability. To accomplish this, these studies use apriori categorizations of human variability that are based on the inaccurate belief that classical racial categorization schemes delineate a series of isolated breeding populations.." An example of contradictory results are seen in the work of such researches as Bowcock, Bowcock, Sforza, et. al, 1994.

-

"Despite a research design that should have maximized the degree to which the researchers were able to classify individuals by racial category, the results are something less than "high resolution" with respect to this goal. For example, 88% of individuals were classified as coming from the right continent, while only 46% were classified as coming from the right region within each continent. Notably, 0% success was achieved in classifying East Asian populations to their region or origin. These results occurred despite the fact that Bowcock and co-workers entered their genetic information into a program that already used the a priori racial categories they were trying to replicate."[67]

Some writers maintain that ironically, some of Bowcock's data itself contradicts "classical" race categories, suggesting that Caucasoids, rather than being a primary group, are a secondary type or race, a hybrid strain based on certain variants of African and Asian populations.[68]

DNA methods and the pre-sorting of data before analysis