Música Rock: o Psicadelismo dos anos 60

|

São Francisco e os hippies

|

Piero Scarufi

Em 1965, São Francisco, cuja cena tinha abrandado nos anos da música "surf" e

do Greenwich Movement, transformou-sesubitamente numa

das cidades mais efervescentes da nação americana.

Os poetas da "Beat generation" mudaram-se para aqui. Os

"Diggers" transfomaram o bairro de Haight Ashbury num "teatro vivo".

Mario Savio fundou "Movimento pela Liberdade de Expressão" ("Free Speech Movement")

na Universidade da Califórnia, em Berkeley, onde as sit-ins e marchas de

protesto eram apoiadas por bandas como a de Country Joe McDonald.

Havia

uma excitação no ar. No Verão de 1965 uma banda de São Francisco, os

Charlatans, e os seus fâns hippies

tomaram conta do "Red Dog Saloon" em Virginia City (Nevada), e deram início à ideia

de tocar um novo tipo de música para uma nova audiência.

Os Warlocks (mais tarde rebaptizados como Grateful Dead) foram contratados por

Ken Kesey para tocar nos seus "acid tests" (festas LSD), onde a banda começou a tocar

longas improvisações musicais, vagamente baseadas na música "country", nos blues e no jazz.

Em Outubro desse ano, a "Family Dog Production" organizou a primeira festa hippie no

"Long Shoreman's Hall". Depois do sucesso desse "festival",

as bandas das avenidas de São Francisco despontaram por todo lado.

1966 foi o "summer of love".

Este movimento corporizava os ideais pacifistas que tinham sido promovidos

por Bob Dylan, mas com menos envolvência política. Tinham uma filosofia de

de vida ("paz e amor", e drogas) que era, de várias formas, consequência

daquilo que Bob Dylan tinha prégado, mas que estava mais próximo da filosofia

Budista.

Os Hippies juntavam-se não para marchar, mas para celebrar;

não para protestar, mas para se alegrarem. A experiência espiritual sobrepunha-se

à experiência política. Isto representou uma mudança dramática relativamente

aos tempos do rock'n'roll, em que a música representava um acto de rebelião, eventualmente violento.

Os festivais de rock foram inventados com o "Human Be-in" que teve lugar em Janeiro

de 1967 no Golden Gate Park ("Gathering of the Tribes"). O fenómeno hippie era interessante

porque se transformou num movimento de massas que se espalhou rapidamente pelos Estados Unidos

(e pelo mundo) mas nunca teve um líder. Era um movimento messiânico sem um messias.

A música dos hippies era uma evolução do folk-rock, rebaptizada como

"acid-rock", porque a ideia inicial fora a de proporcionar uma trilha sonora

para as festas de LSD, uma trilha sonora que reflectisse tão aproximadamente quanto

possível os efeitos de uma "viagem" de LSD.

Esta música era uma espécie de equivalente rock da pintura abstracta

(Jackson Pollock), do free-jazz (Ornette Coleman) e da poesia beat (Allen Ginsberg).

Este fenómeno tinha em comum uma estrutura solta em que a forma

"era" o conteúdo, assumindo uma atitude de desprezo pelos valores estéticos velhos de

um século.

Na música isto significava que a improvisação era importante, e até

mais importante do que a composição. A principal invenção do acid-rock

foi a "jam" (sessão de improvisação) que, evidentemente, já era

praticada há muito pelos músicos de jazz e blues.

Os músicos de acid-rock improvisavam num contexto ligeiramente diferente:

davam mais ênfase à melodia, menos ênfase ao virtuosismo da perfomance.

A diferença mais visível (para além da côr dos músicos) era o papel

de liderança da guitarra eléctrica. Uma diferença mais subtil residia em que

o espírito apaixonado e doloroso dos blues foi substituído por um espírito

transcendental, tipo-Zen.

O arquétipo do acid-rock foi gravado em Chicago, pelo bluesman branco

Paul Butterfield:

East-West (1966), uma peça musical longa em que se fundia a

improvisação afro-americana e indiana.

Do ponto de vista instrumental, o acid-rock descendia do

rhythm'n'blues, mas do ponto de vista vocal descendia da

música folk e country. As melodias e harmonias eram essencialmente inspiradas

na tradição da música dos brancos.

1966 foi o ano de: Virgin Forest pelos Fugs, East-West

por Paul Butterfield, Up In Her Room pelos Seeds,

Going Home pelos Rolling Stones, Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands por Bob Dylan, etc.

Nos anos seguintes os músicos de rock viriam a gravar peças crescentemente complexas e longas.

|

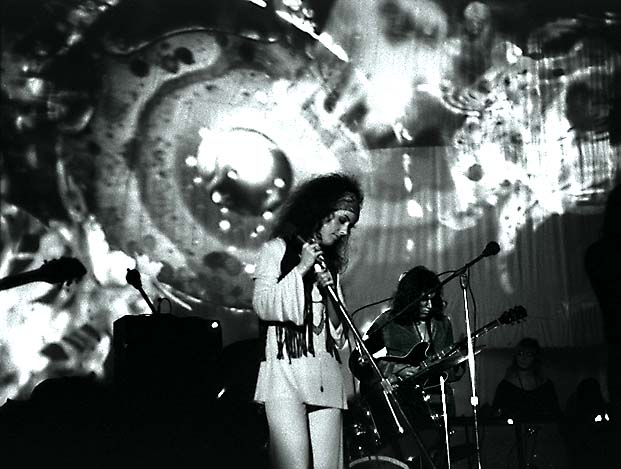

Os Jefferson Airplane

foram uma das maiores bandas rock de todos os tempos. Não só corporizaram

o som da era hippie mais do que qualquer outra, mas também possuíam um formidável

conjunto de talentos que redifiniram o canto (

Grace Slick, na foto), a harmonia (Paul Kantner, Marty Balin),

a viola baixo (Jack Casady), o contraponto guitarrístico (Jorma Kaukonen)

e a bateria (Spencer Dryden) na música rock.

Os seus primeiros singles, Somebody To Love e White Rabbit,

ajudaram a estabelecer o "rock psicadélico" como género músical.

|

|

A música dos Jefferson Airplane era largamente auto-biográfica, e as suas

carreiras servem como documentário da sua geração.

O albúm Surrealistic Pillow (1967) era um manifesto da geração hippie.

After Bathing At Baxter's (1967), um dos grandes feitos musicais da

era psicadélica, foi o albúm que quebrou com as convenções de formatação da

canção e dos arranjos pop.

Volunteers (1969), a sua suprema obra-prima, fundia a tendência mais recuada

com um retorno às origens (tanto musicais como morais) e a tendência mais

avançada com a política dura.

Blows Against The Empire (1970) foi um olhar atrás nostálgico

para os ideais das comunas e um tributo utópico à idade espacial.

Sunfighter (1971) foi um retorno adulto e solene ao formato da

canção e à natureza.

O "marketing appeal" dos Jefferson Airplane estava em que eles representavam

(e praticavam) um novo estilo de vida. Infelizmente poucos dos seus albúns estão

incluídos nas obras-primas do rock porque estavam fundamentalmente limitados ao

formato-canção que raramente tentaram ultrapassar (como, por exemplo, os Grateful Dead).

Os Jefferson Airplane foram parcialmente aceites pelo sistema porque as raizes

folk e blue eram ainda visíveis, porque a melodia constituía ainda o núcleo central.

| |

Entretanto, havia quem reagisse contra tudo o que foi referido acima.

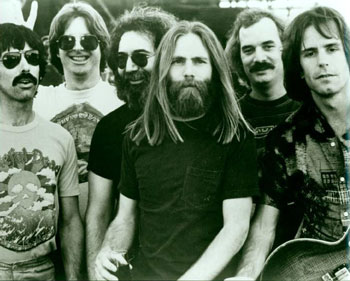

Os Grateful Dead,

considerados por muitos como "a" maior banda de rock de todos os tempos,

eram um monumento na civilização hippie de São Francisco e, de um

modo geral, um monumento da civilização psicadélica dos anos 60.

A sua maior invenção foram as longas e informais improvisações colectivas,

o equivalnte rock da improvisação no jazz. Diferentemente do jazz, que

se alimentava da angústia do povo afro-americano,

a música dos Grateful Dead era a trilha musical das "viagens" de LSD.

|

Mas esta música rapidamente passou a representar toda uma ideologia de fuga

ao "establishment", de liberdade artística, de estilo de vida alternativo.

Contrariamente à sua imagem de marginais e inadaptados, os Grateful Dead

eram um dos mais eruditos grupos de todos os tempos, conhecedores

das composições atonais da vanguarda europeia, bem como da improvisão modal

do free-jazz, tal como dos ritmos de outras culturas. Conseguiram transformar

o feedback da guitarra e estranhas métricas no equivalente

rock dos instrumentos de câmara.

As infinitas escalas ascendentes e descendentes de Jerry Garcia estão entre

os mais titânicos empreendimentos tentados pela música rock.

Os Grateful Dead nunca venderam muitos discos. O seu formato

preferido era o concerto ao vivo e não as gravações. Eles literalmente

redifiniram o que era a "música popular"; o concerto ao vivo desafiava as leis do

capitalismo, removendo o "plano de negócios" do divertimento.

As sua obras-primas gravadas,

Anthem Of The Sun (1968), Aoxomoxoa (1969) e

Live Dead (1969), eram meras aproximações da sua arte.

Anthem Of The Sun foi redifinido em estúdio usando todo o

tipo de efeitos e técnicas. A banda procurou Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage e

Morton Subotnick (não Chuck Berry) para inspiração.

As raízes blues e country dos Grateful Dead eram horrivelmente desfiguradas

pelo pulsão alucinogénica, desintegrando a estrutura e o desenvolvimento da

canção. Cada peça tornava-se numa orgia de som amíbico.

A bateria entregava-se a ritmos obsessivos para reproduzir

as pulsações provocadas pelo LSD. Com a electrónica pintaram paisagens musicais

fantasmagóricas; as teclas soavam tristes e misteriosas, como fantasmas

aprisionados em catacumbas; as guitarras perfuravam as mentes e libertavam

os seus sonhos para o céu; as vozes flutuavam, serenas, sobre a tempestade.

Os arranjos vibravam com pedaços de música de cravo,

trompete, celeste, etc. Mas o sentimento geral era de angústia

salientado pela selva de dissonâncias e percussões.

As cada vez mais longas improvisações soavam como uma espécie de música de câmara para

marginais (junkies). O produtor Dave Hassinger deve ser creditado

por ter feito a mistura de diferentes performances, criando um sentimento

"multi-dimensional", uma versão extrema da "muralha de som" de Phil Spector).

O ritmo e a melodia tinham-se tornado acessórios.

Aoxomoxoa veio reparar parte dos estragos, reorientando-se para o

tradicional formato de canção. Live Dead levou-os à

sua verdadeira dimensão com faixas tais como

Feedback, uma longa "trip" monolítica pela guitarra de Jerry Garcia e

Dark Star, a "jam" terminal dos Grateful Dead e canto do cisne do acid-rock.

Ao mesmo tempo, contudo, as suas improvisações livres nasciam de uma filosofia

que era ainda profundamente americana. Eles tinham nascido na fronteira

entre a cultura individualista e libertária da "Frontier" e a cultura comunitária

e espiritual dos quakers. Apesar de serem ostracizados pelo

"Establishment", os Grateful Dead expressaram, melhor do que qualquer outro

músico dessa época, a essência da nação Americana e foi isso que fez com que a sua música vibrasse tão bem na alma da juventude americana.

Não é uma coincidência que os Grateful Dead, juntamente com os Byrds e Bob Dylan, tenham levado o movimento em direcção ao country-rock, via

Workingman's Dead (1970) e o albúm a solo de Jerry Garcia,

Garcia (1972).

A banda ocupou os seus anos de maturidade tentando transformar

o idioma subcultural dos hippies numa linguagem universal que pudesse

atingir qualquer esquina do planeta, e não apenas as comunas hippies.

Eles conseguiram-no com uma forma de "muzac" intelectual que considerava a

"viagem" lisérgica como um escape catárquico da realidade e de libertação

das neuroses urbanas: Weather Report Suite (1975), Blues For Allah (1975),

Shakedown Street (1978), Althea (1979).

Na prática, a sua arte era uma busca psicológica da relação entre os

estados alterados da mente (alucinações psicadélicas)

e os estados alterados da psique (neuroses industriais).

As primitivas bandas de São Francisco tiveram de lidar com uma

indústria de gravação que nunca os compreendeu. As grandes companhias

estavam apostadas em explorar o fenómeno hippie, mas recuaram

perante a estranha música que estes hippies tocavam. Os produtores eram pagos para

destruir o som original e "normalizar" as "jams" (por outras palavras, para

"Beatle-izar" o acid-rock).

acid-rock).

Os Kaleidoscope

estavam entre os que mais se aventuraram na fusão da música country,

jazz, cajun, middle-eastern, indiana, flamenco, cigana and sul-americana com

Side Trips (1967) e A Beacon From Mars (1968), este último

incluindo Taxim (possivelmente a obra-prima do raga-rock).

Os Electric Flag de Mike Bloomfield estrearam-se com

Trip (Edsel, 1967), uma bizarra mistura de electrónica, ruído,

psicadelismo, country, ragtime e blues.

Os Moby Grape corporizaram o espírito informal e mágico

das "acid jams" em Grape Jam (1968), com Mike Bloomfield e Al Kooper

(ambos músicos que colaboravam com Dylan), e no albúm a solo de Alexander Spence, Oar (1969).

Os Quicksilver, uma das grandes bandas de "jam" da cena acid-rock,

ligaram o acid-rock de São Francisco, o som de garagem do Northwest

os "rhythm and blues" de Chicago, particularmente em

Happy Trails (1969), cujas faixas mais longas

são ousadas cavalgadas estilísticas que partem dos blues mas apontam para o

"si" interior.

Os Mad River foram também influenciados pelos blues em

Mad River (1968) e

Paradise Bar And Grill (1968).

Os Blue Cheer, por outro lado, tocavam um blues-rock vingativo:

Vincebus Eruptum (1968) introduziu um som terrífico

(amplificações ensurdecedoras das guitarras e do baixo), que anteciparam o stoner-rock em 25 anos.

Os SteppenWolf gravaram dois dos hinos deste ruidoso e rápido acid-rock:

Born To Be Wild (1968), onde se encontra a expressão "heavy metal" que haveria de identificar

um novo género musical, e Magic Carpet Ride (1968).

No extremo deste espectro estavam os

Fifty Foot Hose uma das bandas mais experimentais dos anos 60

e uma das primeiras a empregar electrónica e a fazer a ligação entre a música rock e a

de vanguarda; gravaram Cauldron (1968), desafiando a plácida atmosfera do

acid-rock com a cacafonia e o caos do seu apocalíptico Fantasy.

Quando estas bandas chegaram aos estúdios de gravação a era dourada do acid-rock

já tinha terminado graças a dois acontecimentos altamente publicitados no

Verão de 1967: o festival de Monterey (que ligitimou o formato)

e o albúm Sgt Pepper dos Beatles (que legitimou o som).

Durante esse Verão a "alternativa" tornou-se "corrente principal".

O espírito anti-comercial do acid-rock tornou-se uma contradição

de termos. No ano seguinte as bandas hippie adoptaram o country-rock e voltaram ao

tradicional formato-canção.

Houve também um motivo socio-político para o súbito abandono do

movimento hippie. Os hippies nunca representaram verdadeiramente a classe intelectual.

Tinham representado o jovem médio da classe média, que tinha medo de ser recrutado

para guerra do Vietename e que sonhava com um mundo sem armas nucleares.

Os intelectuais da ala esquerda tinham diferentes prioridades e

aderiram à noção de que uma qualquer forma de guerrilha urbana era necessária

para mudar o "Establishment". Os hippies eram apenas uma das facetas

da contra-cultura. Em 1968 a maré mudou, e os protestos violentos tornaram-se

mais populares do que os pacíficos. O movimento da paz foi sequestrado

por revolucionários de um diferente calibre, e a sua trilha sonora - o acid rock.

tornou-se anacrónico.

|

Nova Iorque e a nova boémia

|

Piero Scarufi

Bandas como a nova-iorquina Velvet Underground pouco tinham de comum com as bandas de San Francisco: representavam a cultura da "heroína" (a qual era mais sinistra, neurótica e niilista) e não a cultura do LSD (que era bucólica, sonhadora, utópica). Os Velvet Underground escavavam as estreitas vielas das zonas degradadas da cidade, e escavavam o subconsciente da juventude urbana, à procura de cicatrizes emocionais que constituíam um sub-produto bárbaro do espírito original do rock&roll. O seu objectivo apenas marginalmente se identificava com a reprodução sonora da experiência psicadélica. O seu verdadeiro objectivo era realizar o documentário do espírito decadente e cínico que se espalhava entre a intelectualidade.

Não se tratava portanto de hippies, mas sim de músicos elitistas que tinham consciência dos movimentos "avant-garde": tinham iniciado as suas actividades musicais, em 1965, como parte de um show de multimédia do artista plástico Andy Warhol: "The Exploding Plastic Inevitable".

Eles deram origem à corrente "pessimista" da música psicadélica – em oposição à corrente "optimista" de San Francisco. Os Velvet Underground foram provavelmente a banda mais influente da história da música rock. Acima de tudo, eles originaram o espírito de criar música (que era independente, niilista, subversivo) que 10 anos mais tarde será rotulado como "punk". A música rock, tal como existe nos nossos dias, nasceu no dia em que os Velvet Underground entraram num estúdio de gravação. The Velvet Underground And Nico, de 1967 (gravado na Primavera de 1966) inclui um impressionante número de obras-primas, quase todas assinadas por Lou Reed e John Cale, e cantadas por Nico: as odes geladas, espectrais de Femme Fatale, All Tomorrow's Parties e Black Angel's Death Song, o boogie ritmado de Waiting For My Man, o caos orgásmico de Heroin, a música tribal dissonante de European Son, o raga indiano embebido com o tédio decadente de Venus In Furs.

Há uma imersão da atmosfera escura e opressiva do expressionismo alemão e do existencialismo francês, mas também se exala uma libido épica: cada canção era um fetiche sexual e uma libertação catárquica sado-masoquista. É difícil encontrar um antecessor dos Velvet Underground porque estes bárbaros vinham do ambiente do lieder clássico e do minimalismo de LaMonte Young, tendo retirado muito pouco do rock'n'roll ou da música pop. Embora menos impressivo, o álbum White Light White Heat, de 1967, inclui Sister Ray, que provavelmente representa a definitiva obra-prima do rock, um peça épica que rivaliza com as sinfonias de Beethoven e as improvisações metafísicas de John Coltrane. O álbum Live, de 1974, contém mais algumas sessões de improvisação incontrolada no estilo de Sister Ray, enquanto que as baladas dos álbuns Velvet Underground, de 1969, e Sweet Jane, de 1970, deram origem à canção pop decadente que teria grande influência no "glam-rock".

Juntando a dependência da droga com o sexo desviante, os Velvet Underground revelaram uma nova categoria de rituais hedonistas. Os seus álbums evocam uma visão dantesca na qual a fronteira entre o inferno e o paraíso aparece pouco definida. Essas canções eram únicas também porque fundiam a elegia fúnebre com o hino triunfal: eram simultaneamente terríveis e sedutoras. Semioticamente falando, aquelas canções constituíam "signos" por meio dos quais a realidade era codificada em sons: a metrópole era reduzida a um interminável ruído pulsante, a vida diária era reduzida a um delírio inconsciente e tudo, fosse privado ou fosse público, aparecia enevoado numa pura libido freudiana.

O hiper-realismo dos Velvet Underground era deformado por uma mente constantemente subjugada por drogas e fantasias perversas. Simultaneamente, a sua música era um caos visionário de cujo nevoeiro se podia elevar a miragem de um mundo melhor. A música era sempre majestática, mesmo quando mergulhava nas profundezas da abjecção.

As restantes bandas de Nova Iorque representavam uma pálida imagem quando comparadas com os Velvet. Os Blue Magoos lançaram em 1966 um dos primeiros álbuns psicadélicos, e os Mystic Tide criaram alguns dos primitivos hinos psicadélicos, nomeadamente Frustration (1966) e Psychedelic Journey (1966).

O rock psicadélico cedo se tornaria tão codificado como qualquer outro género. Poucas bandas se aventuravam fora do dogma, e aquelas que o faziam desapareciam na obscuridade... Por exemplo, os Devils’ Anvil tocaram um rock "ácido" único, imortalizado em Hard Rock From the Middle East (1967).

Os Pearls Before Swine de Tom Rapp foram talvez a maior banda a aventurar-se no folk psicadélico durante os anos 60. As suas duas obras-primas, One Nation Underground (1967) e especialmente Balaklava (1968) constituem mosaicos de canções atmosféricas que desafiam qualquer classificação, evocando os estados alucinatórios do surrealismo daliniano, influenciados tanto pela música clássica como pelo jazz. Cada álbum era executado por um verdadeiro "ensemble" clássico: órgão, harmónio, piano, harpa, vibrafone corne-inglês, clarinete, celesta, banjo, sítara, flauta...

Igualmente típicos do meio artístico nova-iorquino eram os Cromagnon, que gravaram um dos álbuns mais radicais e assustadores daquela era: Orgasm (1968).

Arranjos bizarros e ecléticos dominavam United States Of America, de 1968, o único álbum gravado pela banda United States Of America de Joseph Byrd, uma mistura de experiências sonoras que dificilmente se podem designar como "canções Sendo um dos mais significativos álbuns daquela era, foi também um dos primeiros álbuns onde um conjunto de instrumentos de teclas (e não apenas piano ou órgão) "pintam" a maior parte da paisagem sonora.

Existem exemplos de técnicas de colagem, baladas jazzísticas e música ambiental futurística: ideias que serão retomadas três décadas mais tarde. O music-hall surrealista de Byrd era o oposto do teatro político dos Fugs. Uma boa designação para este típico de música seria o título do álbum a solo de Joseph Byrd, American Metaphysical Circus, de 1969.

Piero Scarufi

O rock-psicadélico de Los Angeles descendia claramente dos Byrds,

mas separou-se depois em diferentes campos:

o "poppy", novidade estereotipada,

melhor representada por Incense And Peppermint (1967) dos

Strawberry Alarm Clock;

a "rave-up" selvagem, bruta, "bluesy",

influenciada pelos Rolling Stones, cujo arquétipo foram os

Seeds, punks lascivos que gravaram os desagradáveis albúns

Seeds (1966) e A Web Of Sound (1966);

a improvisação em torno da guitarra, longa e intoxicante, cujos heróis

foram os Iron Butterfly, banda que lançou o albúm Heavy (1967)

antes mesmo do termo "heavy-metal" aparecer,

e o febril blues psicadélico com o título In A Gadda Da Vida (1968).

A frágil e sonhadora música de Part One (1966), albúm de estreia dos

West Coast Pop Art Band foi provavelmente o mais próximo do acid-rock de

São Francisco que Los Angeles produziu.

Os Love foram representativos de três diferentes estádios do

rock-psicadélico: as suas raízes no folk-rock, ainda evidentes no

ingénuo Love (1966); a sua maturidade creativa, depois de

digerir os blues, o jazz e o raga, como na sua obra-prima

Da Capo (1967); o seu apogeu barroco quando, influenciados

(como todos os outros) pelo Pet Sounds dos Beach Boys, a banda

adoptou os arranjos pop para Forever Changes (Dezembro de 1967).

De todas as bandas da história da música rock, os Doors

talvez tenham sido os mais criativos. O seu primeiro albúm,

The Doors (1967), inclui apenas obras-primas:

Light My Fire, Break On Through, Crystal Ship,

Soul Kitchen, End Of The Night, e a canção com maior suspense da

história da música popular The End.

O seu vocalista, Jim Morrison, definiu o vocalista rock como artista,

não apenas como cantor.

Quer se deva a ele, a Bobbie Krieger ou Ray Manzarek, ou a todos em conjunto,

as suas canções possuem uma qualidade que nunca depois foi alcançada.

Eram metafísicas ao mesmo tempo que psicológicas e "físicas"

(eróticas e violentas). É o mais próximo de William Shakespeare que a música rock produziu.

Em parte psicodrama freudiano e em parte invocação xamanística/messiânica,

as canções dos Doors eram sempre mais do que "canções".

O facto de utilizarem elementos dos blues, Bach e ragas, é menos relevante do que

o facto de representarem agonias suicídas auto-infligidas. Continuamente se

reportam à morte: sexo, drogas e morte fazem a realidade tríptica dos Doors.

Cada uma delas era êxtase e aniquilação. A qualidade sobrenatural dos seus hinos

não era gótica, mas antes influenciada pelo fatalismo dos simbolistas franceses.

A morte era o derradeiro aspecto dessa trindade, como Morrison descobriu em 1971.

Os Doors fizeram mais três albúns que manifestam o seu talento:

Strange Days (1967), Waiting For The Sun (1968) e

L.A. Woman (1971), mas nunca repetiram o feito do seu primeiro albúm.

Tecnicamente falando, os Spirit tinham ainda mais talento do

que os Doors. Gravaram alguns dos mais aventurosos albúns da era

psicadélica, utilizando fequentemento elementos do jazz e da música clássica,

antecipando o rock progressivo.

Spirit (1968) e The Family That Plays Together (1969) brincavam com

uma fusão erudita de blues, jazz, raga e rock, enquanto que

Twelve Dreams Of Dr Sardonicous (1971) movia-se na direcção de arranjos

mais rudes recorrendo à electrónica.

O rock-psicadélico foi um achado para os produtores de

Los Angeles, porque lhes deu uma desculpa para se permitirem toda a espécie de

arranjos bizarros. O produtor Ed Cobb contribuíu com um banda artificial,

Chocolate Watchband, a quem creditou o seu

The Inner Mistique (1967).

David Axelrod produziu Mass In F Minor (1968) para os

Electric Prunes, a primera "missa rock".

|

Sounds of the Psychedelic Sixties

|

by Lucy O'Brien

In 1967 the Beatles were in Abbey Road Studios putting the finishing touches on their albúm Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. At one point Paul McCartney wandered down the corridor and heard what was then a new young band called Pink Floyd working on their hypnotic debut, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. He listened for a moment, then came rushing back. "Hey guys," he reputedly said, "There's a new band in there and they're gonna steal our thunder."

With their mix of blues, music hall influences, Lewis Carroll references, and dissonant experimentation, Pink Floyd was one of the key bands of the 1960s psychedelic revolution, a pop culture movement that emerged with American and British rock, before sweeping through film, literature, and the visual arts. The music was largely inspired by hallucinogens, or so-called "mind-expanding" drugs such as marijuana and LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide; "acid"), and attempted to recreate drug-induced states through the use of overdriven guitar, amplified feedback, and droning guitar motifs influenced by Eastern music.

This psychedelic consciousness was seeded, in the United States, by countercultural gurus such as Dr. Timothy Leary, a Harvard University professor who began researching LSD as a tool of self-discovery from 1960, and writer Ken Kesey who with his Merry Pranksters staged Acid Tests--multimedia "happenings" set to the music of the Warlocks (later the Grateful Dead) and documented by novelist Tom Wolfe in the literary classic The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968)--and traversed the country during the mid-1960s on a kaleidoscope-colored school bus.

"Everybody felt the '60s were a breakthrough. There was exploration of sexual freedom and [a lot of] drugs around that were essential to the development of consciousness," recalls British avant-garde filmmaker Peter Whitehead, whose movies include Tonite Let's All Make Love in London (1967) and the Rolling Stones documentary Charlie Is My Darling (1966). "The zeitgeist of the time was the final collapse of a certain kind of thinking. The seeds were sown for feminism, for the whole notion of cyberspace, ecology, and the whole philosophy of Gaia."

Suzy Hopkins, formerly Suzy Creamcheese, a dancer and inspirational figure on the underground scene in Los Angeles and London, remembers the visceral way psychedelic culture affected the senses. "There's a difference between a drug and a psychedelic. Drugs make you drugged and psychedelics enhance your ability to see the truth or reality," she says. For her, LSD and music created a kind of alchemy. "When I start to dance, at a certain point, the dance takes over and the music is dancing me. Dancing is this electric enhancement of your spine by sound."

Many psychedelic bands explored this sense of abandonment in their music, moving away from standard rock rhythms and instrumentation. The Grateful Dead of San Francisco, for instance, created an improvisatory mix of country rock, blues, and acid R&B on albums like The Grateful Dead (1967) and Anthem of the Sun (1968), while another 'Frisco band, Jefferson Airplane (fronted by the striking vocalist Grace Slick), sang of the childlike hallucinatory delights of an acid trip in the 1967 Top Ten hit "White Rabbit."

In Los Angeles the multiracial band Love played whimsical, free-flowing rock, fueled by the unique vision of their troubled frontman Arthur Lee. A typically eccentric line from their third album, Forever Changes (1968), satirizes hippie dinginess: "The snot has caked against my pants." Also from Los Angeles, the Byrds plowed a different furrow, creating a jangly psychedelic folk augmented by rich vocal harmonies and orchestration. With such hits as "Eight Miles High" and their cover of Bob Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man," they, along with the brooding intensity of the Doors, were among the most commercially successful of the West Coast bands. Another important Los Angeles act was the United States of America, a band led by electronic music composer Joe Byrd, whose eponymous 1968 debut album blends orchestral pastoral with harsh, atonal experimentation.

Meanwhile the 13th Floor Elevators from Austin, Texas, epitomized the darker, more psychotic frenzy of acid rock. Featuring the wayward talent of Roky Erickson, a gifted musician and songwriter who was later hospitalized for mental illness, the band played visionary jug-blowing blues. The track "Slip Inside This House," for instance, on Easter Everywhere (1967), conveys a sense of mysticism and transcendence, enhanced by acid. Erickson's occult explorations took him so far that by the time the band split in 1969 he believed Satan was following him everywhere.

On the East Coast the Velvet Underground echoed the sonic techniques of psychedelia with their use of repetition and electronic improvisation. Their attitude, though, was more about nihilistic art-school cool than the more playful "flower power." This was accentuated in the drugs they celebrated in song--speed and heroin, for instance, rather than LSD.

Established rock bands began to introduce psychedelic elements into their music, notably the Beatles, with such records as Revolver (1966), featuring the pounding mantra of "Tomorrow Never Knows"; Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), with the trippy lyrics of "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds"; Magical Mystery Tour (1967), showcasing the swirling surrealism of songs like "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "I Am the Walrus"; and The Beatles (1968; the "White Album"), containing the standout track "Revolution 9," an experimental collage of found sounds.

The Beach Boys, too, branched out with the expansive, haunting Pet Sounds (1966), an album masterminded by an introspective Brian Wilson. The Yardbirds, with Jeff Beck on guitar, scored a hit with the echo-laden "Shapes of Things" (1966). Encouraged by Brian Jones, who was drawn to instruments like the sitar and ancient Eastern percussion, the Rolling Stones dipped their feet into the scene with songs like "Paint It Black" (1966) and the less-successful album Their Satanic Majesties Request (1967).

In Britain psychedelic pioneers created music that was steeped in whimsy and surrealism and was less aggressive and minimalist than their American counterparts. The scene revolved around venues such as London's UFO club (a predecessor to festivals like Glastonbury) and Middle Earth and such events as the 14-Hour Technicolour Dream, a happening in April 1967 in the Alexandra Palace that featured an enormous pile of bananas and bands like Pink Floyd, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown, and the Utterly Incredible Too Long Ago to Remember Sometimes Shouting at People. A benefit for the alternative newspaper IT (International Times), the event also drew counterculture celebrities such as John Lennon, Yoko Ono, and Andy Warhol.

Pink Floyd was the leading light of the British underground scene, with vocalist/guitarist Syd Barrett the main writer behind such hits as "Arnold Layne" (a quirky, controversial song about a transvestite), and the spacey, driving instrumental "Interstellar Overdrive." He was a strong creative force until his worsening schizophrenia led to him being edged out of the band in 1968. Other British acts included the anarchic Tomorrow, which specialized in droning raga feedback and wild drumming; the operatic, flamboyant Arthur Brown; the R&B-flavored Pretty Things, and the Canterbury band Soft Machine, which incorporated "harmolodic" jazz into their psychedelic rock.

"Musically people were experimenting, trying to convey that transcendant feel. Even the Stones did it, shooting off at an angle that didn't suit them," sums up Andy Ellison, lead vocalist with John's Children, the first band of Marc Bolan, who later fronted T. Rex. "It was like soul music came from white boys on acid and took on a whole different meaning."

Psychedelic rock - which had already revolutionized fashion, poster art, and live performance - continued to grow after the 1960s, influencing a host of subgenres, including heavy metal, progressive and art rock, "Kraut-rock" (experimental electronic music by German bands such as Tangerine Dream), and the space-age funk of Parliament-Funkadelic (which, along with Jimi Hendrix, proved to be a key connection between black funk and psychedelia). Moreover, psychedelic rock's influence was evident in later genres, from punk to trip-hop to acid-house dance. As Paul McCartney said in 1967, psychedelia meant musical liberation: "The straights should welcome the Underground because it stands for freedom."

|

The Long, Strange Trip Continues

|

by Jim DeRogatis

Of rock 'n' roll's myriad genres, psychedelia may well be the hardest to get a grip on. Like punk music, it is a sound based largely on knocking down doors--or breaking on through to the other side, to quote Jim Morrison of the Doors (who borrowed the sentiment from novelist Aldous Huxley, who, in turn, drew inspiration from transcendent Romantic poet William Blake). Punk could at least be defined by the things that it negated, but at its best, psychedelic rock remains an ever-changing genre that refuses to accept any rules.

Nevertheless, the significance of these swirling and sometimes disorienting "head sounds" can be found by examining their evolution from the 1960s to the '90s and by going back to the roots of the word itself. (Contrary to nostalgic accounts, psychedelic rock did not begin and end in San Francisco during the 1967 Summer of Love.)

The term "psychedelic" originated in correspondence during the early 1950s between two pioneers in the study of psychoactive drugs: Humphry Osmond, a British psychiatrist who studied the effects of mescaline and LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide; "acid") on alcoholics in Canada, and Huxley, the English author of Brave New World (1932) and The Doors of Perception (1954). These men needed a word to describe the effects of the drugs they themselves were taking, and Osmond suggested "psychedelic" from the Greek words psyche (soul or mind) and delein (to make manifest) or deloun (to show or reveal). He illustrated its use in a rhyme: "To fathom hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic."

From the beginning, scientists studying the effects of psychedelic drugs remarked on the way they enhanced the experience of listening to music, sometimes causing "synesthesia," or the illusion of seeing sounds as colors. Albert Hofmann, the Swiss chemist who first synthesized LSD, noted that under its influence, "every sound generated a vividly changing image with its own consistent form and color."

Describing an LSD experience in The Joyous Cosmology (1962), English-born philosopher Alan Watts wrote, "I am listening to the music of an organ; as leaves seemed to gesture, the organ seems quite literally to speak." And Harvard University professor-turned-acid-guru Timothy Leary claimed that while under the influence of psychedelic mushrooms, he "became every musical instrument." Users of hallucinogens also reported that music had the unique ability to conjure the drug experience long after the effects of the chemicals had worn off.

By the late 1950s and early '60s, legal psychedelic drugs were turning up in select circles of authors, artists, and psychiatrists in Los Angeles, New York City, and London. It was inevitable that musicians would experiment with them as well. A studio surf band called the Gamblers was the first rock combo to mention LSD on record. Their instrumental "LSD 25" was the B-side of "Moon Dawg," a 1960 single on the World Pacific label, but the twangy guitar and barrelhouse piano had nothing in common with what would later be considered psychedelic rock. Nor had "Hesitation Blues," a 1963 song by New York folk musician Peter Stampfel, which may have been the first documented use of "psychedelic" in a lyric.

It wasn't until 1966 that the collision of rock and psychedelic drugs began to result in an exciting new style of popular music. Sparked by the soul-searching that followed his first encounter with LSD, Beach Boy Brian Wilson created the breathtaking Pet Sounds (1966). His rivals in the Beatles responded with Revolver (1966), which included "Tomorrow Never Knows," a song likewise inspired by John Lennon's first profound acid trip.

In Austin, Texas, Roky Erickson and his band debuted with an album entitled The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators (1966); its liner notes openly encouraged hallucinogenic experimentation. That year the Rolling Stones scored a hit with the mysterious, Eastern-tinged "Paint It Black." And though they maintained that it was about jet flight, the Los Angeles band the Byrds found their otherworldly single "Eight Miles High" blacklisted by radio programmers across the United States because of its alleged druggy subtext.

Many of these musicians spoke openly about using psychedelic drugs. But by 1966, these substances had been written about enough (often in alarmist terms), so that even teenagers in Middle America who'd never consumed anything more potent than a beer thought that they understood the hallucinogenic experience. In noisy, chaotic singles that would represent rock's first golden age of one-hit wonders, a wave of garage bands imitated British Invasion groups such as the Beatles and the Yardbirds, singing about "bad trips" that often involved careening out of control or losing one's mind.

In 1972 a sampling of lysergic chart-toppers from the 1960s--such as the Electric Prunes's "I Had Too Much to Dream (Last Night)," the Count Five's "Psychotic Reaction," the Seeds's "Pushin' Too Hard," and the Amboy Dukes's "Journey to the Center of the Mind"--would be collected by rock critic Lenny Kaye on an album called Nuggets: Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1965-1968. It would prove hugely influential to the punk movement, illustrating how imagination and attitude were more important in rock than technical expertise.

Even as it blossomed in 1966, it was clear that the hallmarks of acid rock were more important than whether or not the musicians themselves had taken psychedelic drugs. These trademark sounds included circular, mandala-like song structures; sustained or droning melodies; a tendency to incorporate the trance-inducing instruments of other countries (the Indian sitar, the Javanese gamelan, the drums of Joujouka, and the didgeridoo of the Australian Aborigines); heavily altered instrumental sounds; reverb, echoes, and tape delays that created a sensation of vastness or eeriness; and layered mixes that rewarded repeated listenings (especially via headphones).

Rock 'n' roll had always been aimed at prompting a visceral reaction from the body. Here was a new type of rock music aimed at the head. It was Apollonian as well as Dionysian, and it encouraged listeners to transcend their surroundings while shaking their booties.

Rockers were aided in creating these sounds by concurrent advents in recording technology. Bands began to utilize multitrack recording, allowing them to overdub many instruments without having to perform everything live in one take. In addition, FM radio was coming of age in the United States as more stations adopted a free-form rock format, broadening their programming to allow the playing of longer album cuts.

As they grew more successful, artists were able to spend more time in the studio, and this gave birth to concept albums such as Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), released by the Beatles during the height of the Summer of Love. The year 1967 also saw the production of such timeless and ambitious rock records as The Piper at the Gates of Dawn by Pink Floyd, The Velvet Underground and Nico by the Velvet Underground, Are You Experienced? by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Da Capo by Love, Surrealistic Pillow by the Jefferson Airplane, and the self-titled debut by the Grateful Dead.

Meanwhile, the children of the Baby Boom were beginning to celebrate a new youth-oriented counterculture--dubbed "hippie" by some--at extremely visible mass "happenings" such as the 14-Hour Technicolour Dream in London and the much-ballyhooed ongoing scene on the Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. Leary issued his ill-considered call to "turn on, tune in, drop out," and LSD was officially outlawed in the United States. Inevitably, there was a backlash against the hype. The Haight produced as many tragic casualties as it opened minds, and cautionary tales--such as the drug-induced breakdowns of Pink Floyd co-founder Syd Barrett and the 13th Floor Elevators's Erickson--proliferated.

By the turn of the decade, many bands were returning to simpler, more stripped-down sounds (witness the 1968 offerings of The Beatles [the "White Album"] and the Stones's Beggars Banquet). But by no means did psychedelia come to an end. The genre continued to mutate and evolve, flourishing whenever musicians set out to create imaginative new worlds in the studio.

In the early 1970s, artists such as Brian Eno, the Barrett-less Pink Floyd, "space-rockers" Hawkwind, and German "Kraut-rock" groups such as Amon Düül II pioneered the use of analog synthesizers and expanded the notion of the recording studio as an instrument in and of itself on albums such as Eno's 1974 album Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), Pink Floyd's Atom Heart Mother (1970), Hawkwind's Space Ritual (1973), and Amon Düül II's Phallus Dei (1969).

At the same time, progressive rock bands such as Yes, Genesis, and Emerson, Lake and Palmer took advantage of the freedoms won during the first psychedelic era to make ever more complex, virtuosic, and fanciful concept albums, including Close to the Edge (1972), The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974), and Tarkus (1971), respectively.

When the punk revolution ushered in a return to faster and louder rock in the late 1970s, echoes of psychedelia could be heard in artier groups such as Pere Ubu (The Modern Dance; 1978), Wire (Chairs Missing; 1978), and the Feelies (Crazy Rhythms; 1980). In one of its handiest definitions, David Thomas of Pere Ubu called head rock "the cinematic music of the imagination." Like many musicians, he maintained that it was more of an approach toward making and recording music than a style of rock rooted in drugs or in any one era.

Of course, there were also the psychedelic revival bands, and they approached the genre with a much more literal devotion. Listening to such admittedly beguiling albums as Sixteen Tambourines (1982) by the Three O'Clock and Emergency Third Rail Power Trip (1983) by the Rain Parade (both members of the "paisley underground" scene of mid-1980s Los Angeles), as well as Wonder Wonderful Wonderland (1985) by Plasticland of Milwaukee, Wis., U.S., Auntie Winnie Album (1989) by England's Bevis Frond, and the work of British cult heroes Porcupine Tree, you'd be hard-pressed to prove they weren't recorded during the Summer of Love.

In the early 1990s, the explosion of techno and electronic dance music ushered in a new psychedelic rock based on a new psychedelic drug: MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), or "ecstasy." Young listeners consumed the substance (or acted as if they had) while grooving to the otherworldly throb of bass-heavy music at late-night warehouse parties called "raves"--'90s updates of '60s happenings like the famed Acid Tests thrown by Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.

Techno artists such as the Orb (U.F.Orb; 1992), Plastikman (Sheet One; 1994), Orbital (Snivilisation; 1994), and the Aphex Twin (Selected Ambient Works Volume II; 1994) further expanded the acid rock palette with inspired experimentation on the latest technology, including digital synthesizers and samplers.

These machines were also used by psychedelic rappers such as De La Soul (3 Feet High and Rising; 1989) and P.M. Dawn (Of the Heart, of the Soul and of the Cross: The Utopian Experience; 1991), who took hip-hop in directions far from the playgrounds of the Bronx where it was spawned. "To me, psychedelia is finding something tangible that you can hold on to in the unusual," said P.M. Dawn's Prince Be. "That's what any innovator does."

Some critics contended that by the 1990s everything that could be done with rock's familiar guitar, bass, and drums lineup had been done. They were proved wrong not only by grunge music but also by an acid rock underground that continued to produce evocative music. The British band My Bloody Valentine created a kaleidoscopic guitar sound on their hugely influential Loveless (1991) and Oklahoma City's Flaming Lips charted the landscape of whimsical new worlds on albums such as Transmissions from the Satellite Heart (1993) and The Soft Bulletin (1999).

A collective of independent bands from Ruston, La., known as the Elephant 6 Recording Company updated the spirit of Pet Sounds and Revolver for a new millennium. Among their notable works are In the Aeroplane over the Sea (1998) by Neutral Milk Hotel, Music from the Unrealized Film Script, "Dusk at Cubist Castle" (1996) by the Olivia Tremor Control, and Tone Soul Evolution (1997) by the Apples In Stereo. The British group Spiritualized, with Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space (1997), explored the merger of Pink Floyd-style interstellar overdrives with free jazz and gospel music.

Gospel music, you ask? Yes, indeed. A final dimension of psychedelia, from the Greek etymology, is "soul-manifesting"--implying a spiritual dimension that is rarely voiced (though it is worth remembering that Brian Wilson spoke of writing "teenage symphonies to God"). By transcending the ordinary, psychedelic musicians and their listeners attempt to connect with something deeper, more profound, and more beautiful.

As Jerry Garcia, guru of the Grateful Dead, once said, "Rock 'n' roll provides what the church provided for in other generations." And no form of rock music attempts to nourish more souls than psychedelia.

Psychedelic music draws its inspiration from the experience of mind-altering drugs such as cannabis, psilocybin, mescaline, ecstasy and especially LSD. Characteristic features of the style include modal melodies, lengthy instrumental solos, esoteric lyrics and "trippy" special effects such as reversed, distorted, delayed and/or phased sounds.

In the 1960s, in the United States, this sound was particularly characteristic of the West Coast sound, with bands such as the Grateful Dead, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Vanilla Fudge, Tommy James and the Shondells and Jefferson Airplane in the vanguard. Jimi Hendrix and the Doors helped to popularize acid rock, a closely related style of music.

There were also less well known psychedelic bands in outlying regions, such as the 13th Floor Elevators and Bubble Puppy working out of Texas, and the Third Bardo in New York City, a group which had a brief revival in the 1990s. The influence was also felt in black music, where record labels such as Motown dabbled for a while with psychedelic soul, producing such hits as "Ball Of Confusion" and "Psychedelic Shack" (by The Temptations) and "Reflections" (by The Supremes) before falling out of favour.

In Britain, although the psychedelic revolution occurred later, the impact was nonetheless profound within the British music scene. Established artists such as Eric Burdon, The Who and The Beatles produced a number of highly psychedelic tunes. In the case of the Beatles, this was especially the case on the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album (which contains the track "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds", the initials of which spell out LSD - although John Lennon claimed this was a coincidence and that the name was based on the title of a drawing by his small son). They also released "Blue Jay Way", another psychedelic tune, on an EP.

The music of Cream and of very early Pink Floyd is representative of British psychedelia. Independent record producer Joe Meek has been credited with inventing the phasing sound publicised most notably on the first UK hit of the band Status Quo entitled "Pictures of Matchstick Men" but also heard on hits such as Pink Floyd's "See Emily Play", the Lemon Pipers' "Green Tamborine" and Hawkwind's "Silver Machine". "I Can See for Miles" and "Pictures of Lily" by the Who, "Strawberry Fields Forever" by the Beatles and "We Love You" by the Rolling Stones are arguably the best examples of English psychedelic pop.

Links

The Annotated Grateful Dead Lyrics

Crédito: Psychedelicatessen - lista elaborada a partir do artigo de Jon Savage no livro "I Want To Take You Higher" de 1997. Ordem cronológica.

font face="arial narrow">

EUA

- The Byrds - Eight Miles High (1ª versão) - Dezembro de 1965

- The Charlatans - Alabama Bound -

Primavera de 1966

- Bob Dylan - Visions Of Johanna -

Maio 26, 1966

- Jefferson Airplane - Blues From An Airplane -

Maio de 1966

- Country Joe And the Fish - Section 43 -

Agosto de 1966

- The Great Society - Someone To Love -

Verão de 1966

- Captain Beefhart & The Magic Band - Electricity -

Verão de 1966

- Oxford Circle - Foolish Woman -

Outono de 1966

- 13th Floor Elevators - Roller Coaster - Outono de 1966

- Vejtables - Feel the Music -

Outono de 1966

- The Count Five - Psychotic Reaction -

Verão de 1966

- The Misunderstood - Children Of The Sun -

Outono de 1966

- Sons Of Adam - Feathered Fish -

Outono de 1966

- Love - 7 And 7 Is -

Setembro de 1966

- The Beach Boys - Good Vibrations -

Outubro de 1966

- Sopwith Camel - Frantic Desolation -

início de 1967

- The Doors - The Crystal Ship -

Janeiro de 1967

- The Seeds - Mr. Farmer -

Março de 1967

- Kaleidoscope - Keep your Mind Open -

Abril de 1967

- The Electric Prunes - Get Me To The World On Time - Abril de 1967

- Mystery Trend - Johnny Was A Good Boy -

Maio de 1967

- Moby Grape - Omaha - Maio de 1967

- Third Bardo - I'm Five Years Ahead Of My Time -

Verão de 1967

- Jefferson Airplane - White Rabbit -

Junho de 1967

- Tim Buckley - Halucinations - Junho de 1967

- Chocolate Watchband - Are You Gonna Be There (at the Love In) - Junho de 1967

- Big Brother & The Holding Company - Ball And Chain -

Junho de 1967

- Painted Faces - Anxious Color -

Verão de 1967

- The Beau Brummels - Magic Hollow - Agosto de 1967

- Buffalo Springfield - Broken Arrow -

Outono de 1967

- Strawberry Alarm Clock - Incense And Peppermints -

Outubro de 1967

- Love - The Red Telephone -

Novembro de 1967

- The Byrds - Change Is Now -

Janeiro de 1968

- Otis Redding - (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay -

Janeiro de 1968

- The Baloon Farm - A Question Of Temperature -

Março de 1968

- Sly And The Family Stone - Dance To The Music - Março de 1968

- Quicksilver Messenger Service - Pride Of Man -

Maio de 1968

- The Grateful Dead - That's It For The Other One -

Verão de 1968

- Iron Butterfly - In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida -

Setembro de 1968

- Steppenwolf - Magic Carpet Ride -

Outubro de 1968

- The Steve Miller Band - Song For Our Ancestors -

Novembro de 1968

- Lothar and the Hand People - Machines - Novembro de 1968

- Tommy James and the Shondells - Crimson And Clover -

Dezembro de 1968

- White Lightning - William -

início de 1969

- Spirit - Dream Within A Dream - Janeiro de 1969

- Alexander "Skip" Spence - War In Peace - Fevereiro de 1969

- The Youngbloods - Darkness, Darkness -

Primavera de 1969

- Kak - Electric Sailor -

Verão de 1969

- The Grateful Dead - Mountains Of The Moon - Junho de 1969

- Jimi Hendrix - The Star Spangled Banner -

Agosto de 1969

Reino Unido

- The Beatles - Tommorow Never Knows - Abril de 1966

- The Rolling Stones - Paint It Black -

Maio de 1966

- Creation - Making Time -

Julho de 1966

- Donovan - Season Of The Witch -

Agosto de 1966

- The Yardbirds - Happenings Ten Years Time Ago -

Novembro de 1966

- Cream - I Feel Free -

Dezembro de 1966

- The Beatles - Strawberry Fields Forever -

Fevereiro de 1967

- Pink Floyd - Interstellar Overdrive -

Fevereiro de 1967

- Smoke - My Friend Jack -

Fevereiro de 1967

- The Small Faces - Green Circles -

Primavera de 1967

- David McWilliams - Days Of Pearly Spencer -

Primavera de 1967

- The Poets - In Your Tower -

Março de 1967

- The Move - I Can Hear The Grass Grow - Abril de 1967

- The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Are You Experienced ? - Maio de 1967

- The Troggs - Night Of The Long Grass -

Maio de 1967

- Traffic - Paper Sun -

Maio de 1967

- John's Children - Midsummer Night's Scene - Verão de 1967

- The Beatles - It's All Too Much -

Maio / Junho de 1967

- The Attack - Colours Of My Mind -

Junho de 1967

- The Small Faces - Itchycoo Park -

Agosto de 1967

- The Jimi Hendrix Experience - The Stars That Play With Laughing Sam's Dice -

Agosto de 1967

- Pink Floyd - Matilda Mother -

Agosto de 1967

- The Rolling Stones - We Love You -

Agosto de 1967

- The Who - Relax -

Janeiro de 1968

- Kaleidoscope - Flight From Ashiya -

Setembro de 1967

- The Pretty Things - Defecting Gray -

Outono de 1967

- The Herd - From The Underworld - Setembro de 1967

- The 23rd Turnoff - Michael Angelo -

Setembro de 1967

- The Hollies - King Midas In Reverse -

Outubro de 1967

- Svensk - Dream Magazine -

Outono de 1967

- The Idle Race - Imposters of Life's Magazine - Outubro de 1967

- Eric Burdon and the Animals - San Franciscan Nights -

Outubro de 1967

- The Troggs - Love Is all Around -

Outubro de 1967

- Tintern Abbey - Vacuum Cleaner -

Novembro de 1967

- Dantalian's Chariot - Madman Runing Through The Fields - Outono de 1967

- Simon Dupree and the Big Sounds - Kites -

Novembro de 1967

- The Beatles - I Am The Walrus -

Novembro de 1967

- Tommorow - Revolution - Dezembro de 1967

- Fairport Convention - It's Alright, Ma, It's Only Witchcraft - início de 1968

- Status Quo - Pictures Of Matchstick Men -

Janeiro de 1968

- The Apple - The Otherside -

início de 1968

- The Mirror - Faster Than Light -

Maio de 1968

- Nirvana - Rainbow Chaser - Maio de 1968

- Big Boy Pete - Cold Turkey - Maio de 1968

- Family - Me My Friend -

Junho de 1968

- Pink Floyd - Jugband Blues -

Setembro de 1968

- The Crazy World Of Arthur Brown - Fire -

Setembro de 1968

- The Jimi Hendrix Experience - (A Merman I Should Turn To Be) Moon, Turn The Tides... Gently Gently Away - Outubro de 1968

- The Nice - Diamond Hard Blue Apples Of The Moon - Novembro de 1968

- Blind Faith - Can't Find My Way Home -

Agosto de 1969

Links

hip da breakz

|