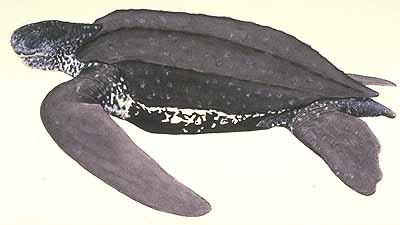

Leatherback Turtle Dermochelys coriacea

| Classification |

Leatherback Basics

The leatherback is the largest of the marine turtles; it has the largest range, dives the deepestand ventures into the coldest water.

· Named for it's smooth, rubbery shell

· It feeds on jellyfish

· There are about 50 nests a year reported in Florida, estimates of 70,000 to 115,000 breeding females worldwide

· The Leather back is a very large turtle: adults weigh 700 to 2,000 pounds and varies between 4 to 8 feet in length

· Hatchlings: Between 2-1/2 inches long

· Nest in Florida from April through July

· Many Leatherbacks die from ingesting plastic debris mistaken for jellyfish

Physical Characteristics

The leatherback is the largest living turtle and is so distinctive that it is placed in its own separate family, Dermochelys.

All other sea turtles have bony hard plates on their shells . The leatherback’s carapace is slightly flexible and has a rubbery texture. No sharp angle is formed between the carapace and the under-belly >plastron) so it is rather barrel-shaped.

Their front flippers are longer than in the other marine turtles, even when you take the leatherback’s size into account reaching 270 cm in adults.

The largest

leatherback on record was a male stranded on the West Coast of Wales in 1988. He weighed

916 kg.

The largest

leatherback on record was a male stranded on the West Coast of Wales in 1988. He weighed

916 kg.

Leatherback hatchlings look mostly black, and their flippers are margined in white. Rows of white scales give hatchling the white striping that runs down the length of their backs.

In 1982, 115,000 adult female leatherbacks are estimated to existed worldwide and that roughly half of them probably were nesting in western Mexico.

Current Status

Endangered

This rare sea turtle lives in warm sea waters and is known to breed off the West

Indies, Florida, the northeastern coasts of South America, Senegal, Natal, Madagascar,

Ceylon, and Malaya.

Occasionally it has been found swimming in cooler waters such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

It is adapted to life in the ocean, it has well developed flippers, with which is swims.

It feeds on jellyfish and other soft-bodied sea animals as well as plants.

Females come ashore in bands and lay their 60 to 100 eggs in holes which have been dug in

the sand. Seven weeks later, when the eggs hatch, the babies rush back to the water.

Compared to other sea turtles, the leatherback appears to have a better chance at

continued survival .

The U.S. government has listed the leatherback as endangered worldwide.

Within the U.S., the leatherback is known to nest in Southeastern Florida, Culebra, Puerto Rico, and St. Croix.

Threats

Leatherbacks have historically been taken only rarely for their meat. The greatest threat continues to be to their eggs.

Nesting Environment

Leatherbacks prefer open access beaches possibly to avoid damage to their soft plastron and flippers. Unfotunately, such open beaches with little shoreline protection are vulnerable to beach erosion triggered by seasonal changes in wind and wave direction. A presumably secure beach can undergo such severe and dramatic erosion that eggs laid on it are lost.

The theft of eggs for local consumption is not currently a problem in Florida but continues in low levels in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Even though the harvest of turtle eggs is illegal in Puerto Rico, law enforcement efforts have been unsuccessful in deterring it.

Leatherbacks are also vulnerable to beach armouring, beach nourishment, artificial lighting, and human encroachment.

Entanglement at Sea

Leatherbacks are the most pelagic of turtles, feeding in the open ocean rather than near shore as other marine turtles do. At sea, they become entangled fairly often in longlines, buoy anchor lines and other ropes and cables. This can result in injury (rope or cable cuts on shoulders and flippers) or drowning.

Ingestion of Marine Debris

Leatherbacks appear to mistake floating plastic in the form of bags or sheets for jellyfish and then eat it. Ten of 33 dead leatherbacks washed ashore between 1979 and 1988 had ingested plastic bags, plastic sheets or monofilament.

Commercial Fisheries

In 1987, it was estimated that offshore shrimp fleets capture about 640 leatherbacks each year. About a quarter (160) die from drowning and many others die when they are injured unintentionally on the decks of these trawlers. Long line fisheries are known to trap their share of leatherbacks as well. Stats are not available about this, however.

Geographic Range

Oceanic Islands, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean: The leatherback sea turtle has been known to inhabit warmer seas around the world, especially tropical seas.

Food Habits

The leatherback turtle is apparently omnivorous and takes both plants and animal. The turtle eats grasses and small animals that they find near the ocean floor and in large marine grass beds.

Reproduction

The leatherback sea turtle, as do many other turtles, reproduces on land. Although they spend most of their lives in the open sea, and are fertilized there, females come out of the water to dig their nests and deposit eggs.

Behavior

It is a very strong swimmer and has been known to travel in the open sea.

Habitat

Open warmer oceans around the world.

Biomes: reef, temperate coastal, tropical coastal

Positive

Despite the fact that many people believe these turtles to be toxic, nesting females are regularly killed for food in some areas such as Guyana, Trinidad, and the Pacific coast of Mexico (National Research Council 1990). Eggs of this species are used as a source of food. Many other species of sea turtles also suffer from the same problems.

Conservation

Status: threatened

The increasing smuggling of this turtle’s unhatched eggs is driving this species towards extinction. In many places around the world the leatherback sea turtle has completely disappeared and in other places its population has decreased dramatically. Many programs are been established to prevent this illegal trade from eliminating this species forever. Nature reserves have been established in the coastal areas where the turtles come to breed to prevent people from stealing the eggs. In some areas, scientist have taken the eggs into captive breeding programs to try to increase the population of the area.

The Recovery Plan for the U.S. Population of Leatherback Turtles:

A substantial

effort is being made by government and non-government agencies and private individuals to

increase public awareness of sea turtle conservation issues. Federal and State agencies

and private conservation organizations.The Atlantic Leatherback is by far the most common

sea turtle recorded in Nova Scotian coastal waters. This may be due to the huge size and

the fact that they frequently become tangled in fishing gear. Most records are from

Halifax County but they can be expected anywhere along the Nova Scotia Coast

Leatherback Turtles are listed as

“Endangered” in Canadian waters by the Committee on the Status of Wildlife in

Canada. This means they are threatened with imminent extinction. All marine turtles are

considered to be endangered species. The adults are captured and used for food, and their

skins and shells are used commercially.

IUCN Status Category: Critically Endangered

The leatherback turtle has survived for a hundred million years, but is now facing extinction.Recent estimates of numbers show that this species is declining precipitously throughout its range. Leatherback numbers in the Pacific have plummeted in the last twenty years: as few as 2,300 adult females now remain, making the Pacific leatherback the world’s most endangered marine turtle. Although Atlantic populations are more stable, models predict that they, too, may also decline, unless measures are taken to halt the large numbers of adults being killed accidentally by fishing fleets.

Biology

Leatherbacks: Their large size is all the more remarkable given their low energy, low protein diet of soft-bodied creatures such as jellyfish, squid and tunicates. These floating organisms can occur in great concentrations near the surface where ocean currents converge or upwell, and these areas are where leatherbacks congregate to feed.

Leatherback populations in the Pacific and Indian Oceans have undergone dramatic declines in the past forty years. For example, the nesting colony at Terengganu, Malaysia went from more than 3000 females in 1968, to 20 in 1993, to just two in 1993. Similar scenarios have occurred in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Mexico. Numbers of females recorded at four formerly major Pacific rookeries have declined to about 250 in Mexico, 117 in Costa Rica, two in Malaysia, and fewer than 550 in Indonesia. Between 1996 and 2000, numbers of female leatherbacks in the eastern Pacific population had dropped from 4,638 to 1,690. The Pacific may now have as few as 2,300 adult females, making the Pacific leatherback the world’s most endangered marine turtle.

Not all leatherback populations have declined: in Southern Africa, three decades of strong protection have increased the small annual nesting population more than fourfold. There have also been increases in nesting in Trinidad, Guyana, Suriname and St. Croix. But, globally, declines in leatherback numbers are precipitous. In 1982, the world population was estimated to be 115,000 adult females, and endangered. By 1994 this had been revised down to about 34,000. The leatherback was reclassified as Critically Endangered in 2000.

Threats

The eggs are harvested intensively, especially in Asia, and it is this practice above all which probably brought about the worldwide decline of the species. Large numbers of leatherbacks also get caught in the nets of shrimp trawlers.

Their feeding habits make leatherbacks vulnerable to fishing vessels using longlines for tuna, swordfish and sharks, because these fish congregate along oceanic fronts and in areas of upwelling, where leatherbacks’ favourite food, jellyfish and other plankton, is also most abundant. As a result leatherbacks are frequently caught as bycatch. Large numbers of leatherbacks also get caught in the nets of shrimp trawlers and, if Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs) are not fitted into the net, most of these animals then drown.

50% of the world population nesting on its beaches, the Guianas may be the world’s most important area for leatherbacks. While leatherbacks are threatened with extinction elsewhere in the world, the Guianas population is still large. The number of leatherback nests in the region has been very volatile. It reached 50,000 in 1992. It has shown a downturn since then, to about 15,000 in 1999. At the same time, the number of recorded nests in Suriname has increased significantly (11,000 in 2000).

Sign Guestbook View Guestbook

|