Loggerhead Turtle

Class: Reptilia: Reptiles |

Diet: Crustaceans |

Order: Chelonia: Turtles and Tortoises |

|

Size: 76 - 102 cm (30 - 40 in) |

|

Family: Chelonidae: Marine Turtles |

Conservation Status:Vulnerable |

Scientific Name: Caretta caretta |

Habitat: coasts, open sea |

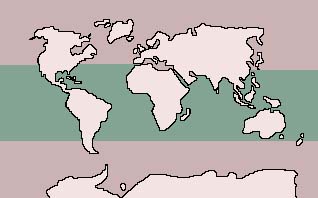

Range: Temperate and tropical areas of the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans |

|

A

Threatened Species

The Atlantic loggerhead turtle: Individuals may attain a shell

length of almost 3 m and weigh up to 454 kg although a weight of about 136 kg is more

usual. In the open sea, these turtles spend much of their time floating on the surface of

the water. They feed upon sponges, jellyfish, mussels, clams, oysters, shrimp, and a

variety of fish.

Nesting takes place in temperate waters and is usually accomplished on open beaches by the

female, who comes ashore at night and digs the nest in the sand with her flippers. The

round, white, leathery eggs, as many as 126 in a clutch, are then covered with packed

sand. In a period of up to 68 days, the eggs which have not fallen victim to predators

hatch, and the young loggerheads struggle to the surface and make their way to the sea.

Loggerhead Quick Facts

The loggerhead is the most common sea turtle in Florida.

- Named for its large head

- Powerful jaws crush mollusks, crabs and encrusting animals attached to reefs and rocks

- An estimated 14,000 females nest in the southeastern U.S, each year

- A large turtle: adults weigh 200 to 350 pounds and measure about 3 feet in length

- Hatchlings: 2 inches long

- Nest in Florida from late April to September

- Survival in Florida threatened by drowning in shrimp trawls and habitat loss

The Loggerhead is a large turtle with a long, slightly tapering carapace, it has a wide chunky head housing powerful jaws, it can crush even hard-shelled prey and feeds on crabs and mollusks as well as on sponges, jellyfish and aquatic plants.

It prefers the warm waters of

tropical and subtropical waters, they are sometimes found in temperate water, prefering

coastal bays, but also found in the open oceans.

It prefers the warm waters of

tropical and subtropical waters, they are sometimes found in temperate water, prefering

coastal bays, but also found in the open oceans.

Loggerheads usually breed every other year and lay three or four clutches of about 100 eggs each in a season. The population has been reduced by overcollection of eggs and lack of hunting controls, but in southeast Africa, where the turtles have been protected for more than 10 years, their numbers have increased by over 50 percent.

Species Status

The Loggerhead was listed in 1978 as a threatened species and it is considered "vulnerable" by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Recent population studies have concluded that the number of females that nest in the Southeast U.S. is continuing to decline.

The U.S. Government listed the loggerhead as endangered worldwide. In the U.S., its nesting areas are divided among four states:

- Florida (91%)

- South Carolina (6.5%)

- Georgia (1.5%)

- North Carolina (1%)

Florida beaches account for one third of the world's total population of loggerheads.

Description

Adults and sub-adults have a reddish-brown carapace. Theplastronis medium-yellow. Average carapace length is about 92 cm and average body mass about 113 kg. Scales on the top and sides of the head and top of the flippers are also reddish-brown, but have yellow borders. The neck, shoulders and limb bases are dull brown on top and medium yellow on the sides and bottom. The plastron is also medium yellow. Adult average size is 92 cm straight carapace length; average weight is 115 kg. Hatchlings are dull brown in color. Average size at hatching is 45 mm long; average weight is 20 g. Maturity is reached at between 16-40 years. Mating takes place in late March-early June, and eggs are laid throughout the summer.

Hatchlings can vary in colour from light to dark brown, its flippers are dark brown with white margins. The plastron and other underparts have a faded yellow ochre appearance.

Surveys as recently as 1990 put loggerhead nest estimates at 50,000-70,000 per year in the Southeast U.S. Representing approximately 35-40% of the world population of loggerhead turtles.

Habitat

Hatchlings are believed to live out their "lost years" in sargassum rafts and/or debris in open ocean drift lines, remaining part of this drifting community, growing to 40 or 50 cm carapace length, then migrateing to the shallower coastal waters which become their foraging habitat.

Some loggerheads live in turbid, detritus-laden, muddy bottom bays and bayous of the northern Gulf Coast, others choose to live in the clear waters of the Bahamas and Antilles, in habitats we more closely associate with tropical marine turtles. Nothing is known about why these creatures would select such vastly different habitats.

Diet

Subadult and adult loggerheads mainly feed upon benthic invertebrates, they sometimes scavenge fish or fish parts, but they are not considered fish eaters.

Reproduction

The loggerhead mating season is from late March to early June. Little is known about its courtship or mating habits(or those of any other sea turtle, for that matter). Reproduction is not well studied and needs further research so that we can better understand their behaviours.

In the southeastern United States, adult females begin to nest as early as late April and they continue right up to early September. Nesting activity reaches a peak in June and July. Average clutch size varies from 100 to 126 eggs along the southeastern United States coast.

Loggerheads nest at night, the average interval between nesting seasons is two to three years, but this can vary from one to six years. Natural incubation periods range from 53-55 days in Florida to 63-68 days in Georgia. The time it takes for eggs to hatch is inversely related to temperature. As with all sea turtles, sex determination in hatchlings is also temperature dependent.

Threats

The loggerhead is vunerable to the same threats that endanger all marine turtles. Because such a significant percentage of the world's loggerhead population lives in Gulf and southwest Atlantic waters, shrimp fishing, gill netting, and activities associated with offshore oil and gas exploitation are particulary dangerous to this species.

Threatened Species

The loggerhead turtle

was listed as threatened throughout its  range on July 28, 1978 (43 FR 82808), and continues

to be. Recent evidence suggests that the number of nesting females in South Carolina and Georgia may be

declining, while the number of nesting females in Florida appears to be stable.

range on July 28, 1978 (43 FR 82808), and continues

to be. Recent evidence suggests that the number of nesting females in South Carolina and Georgia may be

declining, while the number of nesting females in Florida appears to be stable.

Four nesting subpopulations of loggerheads in the western North Atlantic have been identified based on genetic research: (1) the Northern Subpopulation, producing approximately 6,200 nests/year from North Carolina to Northeast Florida; (2) the South Florida Subpopulation, occurring from just north of Cape Hatteras on the east coast of Florida and extending up to Naples on the west coast. The Northern Subpopulation declined through the mid 1980s and thereafter a trend is not detected. Recent surveys of South Carolina nesting beaches (where more than 30% of the nesting of the Northern Subpopulation occurs) indicate a downward trend and thus the subpopulation is stable or declining. The South Florida Subpopulation appears to have shown significant increases over the last 25 years, suggesting the population is recovering, although the trend could not be detected over the most recent 7 years of nesting. An increase in the numbers of adult loggerheads has been reported in recent years in Florida waters without a concomitant increase in benthic immatures. These data may forecast limited recruitment to South Florida nesting beaches in the future. Since loggerheads take approximately 20-30 years to mature, the effects of decline in immature loggerheads might not be apparent on nesting beaches for decades. The recovery team concluded that nesting trends for the loggerhead are generally declining. The most significant threats tot he loggerhead populations is coastal development, commercial fisheries, and pollution.

Loggerhead populations in Honduras, Mexico, Colombia, Israel, Turkey, Bahamas, Cuba, Greece, Japan, and Panama have been declining. This decline continues and is primarily attributed to shrimp trawling, coastal development, increased human use of nesting beaches, and pollution. Loggerheads are the most abundant species in U.S. coastal waters, and are often captured incidental to shrimp trawling. Shrimping is thought to have played a significant role in the population declines observed for the loggerhead.

Biology

Distribution

Loggerheads are circumglobal, inhabiting continental shelves, bays, estuaries, and lagoons in temperate, subtropical, and tropical waters. In the Atlantic, the loggerhead turtle's range extends from Newfoundland to as far south as Argentina. During the summer, nesting occurs in the lower latitudes. The primary Atlantic nesting sites are along the east coast of Florida, with additional sites in Georgia, the Carolinas, and the Gulf Coast of Florida. In the eastern Pacific, loggerheads are reported as far north as Alaska, and as far south as Chile. Occasional sightings are also reported from the coast of Washington, but most records are of juveniles off the coast of California. Southern Japan is the only known breeding area in the North Pacific.

Human Impacts on Loggerhead Sea Turtles

I) Impacts in the nesting environment

- In the United States, killing of nesting loggerheads is infrequent. However, in a number of areas, egg poaching is common.

- Erosion of nesting beaches can result in loss of nesting habitat.

- Development of beachfronts results in fortification to protect property from erosion, resulting in loss of a dry nesting beach. It can also prevent females from getting to nesting sites and wash out nests.

- Beach nourishment impacts turtles by burial of nests, disturbance to nesting turtles, and changes in sand compaction and temperature which may affect embryo development.

- Artificial lighting can cause disorientation or misorientation of both adults and hatchlings. Turtles are attracted to light, ignoring or coming out of the ocean to go towards a light source, increasing their chances of death or injury. In addition, as nesting females avoid areas with intense lighting, highly developed areas may cause problems for turtles trying to nest.

- Repeated mechanical raking of nesting beaches by heavy machinery can result in compact sand and causes tire ruts which may hinder or trap hatchlings. Rakes can penetrate the surface and disturb or uncover a nest. Disposing of debris on the high beach can cover nests and may alter nest temperature.

- A serious threat of nighttime use of a beach is the disturbance of nesting females. Heavy utilization of nesting beaches by humans may also result in lowered hatchling success due to sand compaction.

- The placement of physical obstacles on a beach can hamper or deter nesting attempts as well as interfere with incubating eggs and the sea approach of hatchlings.

- The use of off-road vehicles on beaches is a serious problem in many areas. It may result in decreased hatchling success due to sand compaction, or directly kill hatchlings. Tire ruts may also interfere with the ability of hatchlings to get to the ocean.

- The invasion of a nesting site by non-native beach vegetation can lead to increased erosion and destruction of a nesting habitat. Trees shading a beach can also change nest temperatures, altering the natural sex ratio of the hatchlings.

II) Impacts in the marine environment

- Dredging can destroy resting or foraging habitats. The use of hopper dredges can also kill turtles caught in dragheads.

- Loggerhead turtles eat a wide variety of marine debris such as plastic bags, plastic and styrofoam pieces, tar balls, balloons and raw plastic pellets. Effects of consumption include interference in metabolism or gut function, even at low levels of ingestion, as well as absorption of toxic byproducts. NMFS is currently analyzing stranding data and available necropsy information to determine the magnitude of debris ingestion and entanglement.

- Commercial Fishing:

- 5,000-50,000 loggerheads each year. Most turtles killed are juveniles and sub-adults. Inshore catch and mortality for shrimp trawlers is not known, but is thought to be significant. Bluefish, croaker and flounder trawl fishing are also a serious threat.

- Turtles are taken by gillnet fisheries in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, but the number is currently not known.

- Several thousand vessels are involved in hook and line fishing for various coastal species. The capturing of turtles is not uncommon, but the number is currently not known.

- Pound net fisheries are primarily a problem in waters off of Virginia and North Carolina, however generally turtles are released alive.

- From 1978-1981, 330 turtles were captured in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico EEZ in the Japanese tuna longline fishery. Due to expansion of this fishery, it may have a large impact on turtle recovery.

- Loggerhead turtles are vulnerable to entanglement in trap fishery lines, and subsequent drowning. The impact on the population has not been determined.

- In areas where recreational boating and ship traffic is intense propeller and collision injuries are not uncommon.

- Sea turtles are at risk when encountering an oil spill. Respiration, skin, blood chemistry and salt gland functions are affected.

- Pesticides, heavy metals and PCB's have been detected in turtles and eggs, but the effect on them is unknown.

- Marina and dock development can cause foraging habitat to be destroyed or damaged. It also leads to increased boat traffic, increasing the risk of turtle/vessel collisions.

- Turtles have been caught in saltwater intake systems of coastal power plants. The mortality rate is estimated at 2%.

- Underwater explosions can kill or injure turtles, and may destroy or damage habitat.

- The effects of offshore lights are not known. They may attract hatchlings and interfere with proper offshore orientation, increasing the risk from predators.

- Turtles get caught in discarded fishing gear. The number affected is unknown, but potentially significant.

- Illegal harvesting of loggerhead turtles is uncommon in the U.S. and Caribbean. No estimates of take exist.