Home / Pete's stuff / Not computer games / Pete's Draka page / Draka 2alpha Timeline / Small Arms Development

CSS functionality missing: This site will appear closer to the author's intent in a browser that supports web standards, but it is accessible to any browser or Internet device. If you can read this, CSS (style sheets) is essentially disabled on this page, thus degrading the presentation but not losing any content. That's due to either the CSS file being unavailable from the server, your browser failing to understand it, or viewing in a medium besides a browser screen.

If this page is displayed in a frame, which should happen only when the Geocities/Yahoo server puts them there and not because some other site is displaying my content, please reload this page to bust out of them.

Visit the discussion of the non-English glyphs problem here if the above heading doesn't contain a character that looks like a Greek lowercase alpha, or if you see box symbols or "?" in the middle of non-English words. Try switching character set to UTF-8 to fix them.

Besides the alpha, accent marks are used on a French inventor's name below.

This document is based upon the Small Arms Development appendix that appears in pages 501–519 of "The Stone Dogs". No infringement is intended on that source material. As changes are made to conform with the Draka 2α timeline, it diverges from the original. Although I may not have changed it as much as necessary. If you're interested in the "original", it can be found here on my website as Appendix 15 (Small Arms Development), as I'm hosting a full set of the appendices from the Draka novels. That used to be on Anne Marie Talbott's website as Appendix 11 (Small Arms Development). I typed in several of them for her, including that one, and it seemed a waste to confine the material to only one timeline. Let me know if you spot any errors.

Also, while the text below implies that the Domination is a world power until at least the introduction of the R-7 in 1971, this isn't a given. It was just easier to leave that in for the moment, and alter it later to whatever occurs in the Draka 2α timeline as it develops.

Permission to reproduce the images of the Ferguson Rifle was received from Narragansett Armes, Ltd.—makers of a working replica Ferguson Rifle for sale to collectors. Other images of the weapon, and further historical and practical information, are available in the "This Barbarous Weapon" article by Lance Klein in Muzzle Blasts Online, Vol.5, No.1. The article points out that any timeline making significant use of the Ferguson must include advances in steel production and mass production techniques; I'll have to address those before I feel comfortable with the widespread use of Fergusons in Drakia.

The footnote about the African tribes is based on an OTL article quoting a 1900 issue of Scientific American, claiming "1,151 distinct tribes of natives south of the Zambesi River".

The McGregor "cylindro-conic" bullet is probably not any of the OTL Civil War bullets shown at http://haislip.org/cwbullet/html/history.html. Mostly as there's no mention of the cavity in the back of the bullet. I believe the expansion of the thin sides of the bullet's base engaging the rifling of the barrel is actually more important than the tapered nose in extending range. So, I added a further development to generate the cavity in the back of the bullet, and other changes to create something like the Minié or Burton "ball", in the efforts of Joshua Nicholson. However, it's important to point out that the OTL ones were used in muzzle-loaders, not breech-loaders. Steve Stirling himself recently pointed out that I'd made a potentially disastrous assumption there. So the paragraph after the table for the Nicholson bullet directly includes some of Steve's message to me. But as I'm not much more knowledgeable in this field than what appears here, tell me if there's still anything needing fixing.

Excerpts from:

"A History of Infantry Weapons"

by Colonel Carlos F. Garcia, U.S. Army (Ret.),

Defense Institute Press, Mexico City, 1973.

[Note: until roughly the 1820s, the inhabitants of the Crown Colony of Drakia were commonly referred to as "Drakian(s)", and after that as "Drakan(s)". This text follows that usage.]

The initial migrants to the Crown Colony of Drakia in 1781–1785 included a number of Hessian regiments and Loyalist units of various sizes. A few of these were formally stood down when their members took up the land grants issued by the Crown, but most continued in some form in the Militia, as the organizational structure was too valuable to discard. Many of the new arrivals paraded through the streets of Cape Town (as it was called then) in their finest military array, with little objection from the Governor or the Army. One consideration that weighed heavily at the time of arrival (the "Land Taking") was the paucity of British Army troops in the new territory. To deter the Dutch or French from retaking the colony by force, nearly all of the Army were stationed on or near the coast. But the immigrants would be heading inland to seize their new lands, grants that had often been made without the knowledge or consent of the many tribes that migrated through or lived settled lives there already. Fostered by fear of the unknown, desire to continue friendships struck up on the long sea voyages to the southern tip of Africa, and the system of land allocations made upon arrival, these groups of new Drakians tended to settle together and—at first—contact those outside their own circle only when necessary. That insularity was quickly broken by need to learn from earlier arrivals, and solve the problems that faced all.

The original armament of the newcomers was a mixture of breech-loading Ferguson rifles (25%), muzzle-loading rifles of both the "Kentucky" and "German/Jaeger" varieties (10%) and ordinary Brown Bess smoothbores (65%). All of these weapons were flintlocks, but their performance differed widely, as follows:

| Brown Bess (Tower musket) | |

| Caliber: | 19.05 mm (.75 inch) |

| Weight: | ~5 kilograms |

| Range: | 65 meters effective, 135 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 2–4 rounds per minute |

| Operation: | Muzzle-loading |

| Kentucky Rifle | |

| Caliber: | 12.7 mm (.50 inch) |

| Weight: | 4 kg |

| Range: | 135–180 m effective, 365 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 1–2 rounds per minute |

| Operation: | Muzzle-loading |

| Ferguson Rifle (with round ball) | |

| Caliber: | 15.42 mm (.607 inch) |

| Weight: | 4 kg |

| Range: | 180–230 m effective, 365 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 4–6 rounds per minute |

| Operation: | Lever-operated screw plug, breech loading |

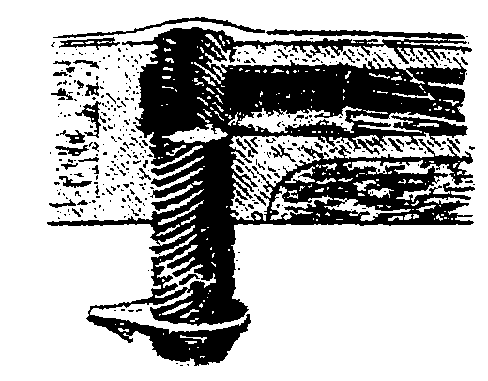

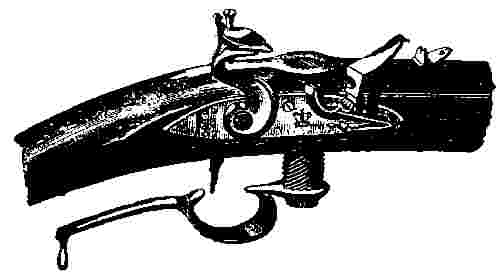

The Ferguson rifle, invented by Patrick Ferguson (b. 1744, Pitfours, Aberdeenshire, d. 1807, Cape Town, Crown Colony of Drakia), was obviously the best weapon of those available. The breech was blocked by a vertical plug, coarsely threaded like a giant bolt. The lower end was attached to the front of the movable trigger guard of the weapon, which had a wooden handle affixed to the rear behind the hand-grip. A complete 360-degree turn lowered the plug and exposed the chamber of the rifle. A round ball and paper cartridge of black powder were then loaded, the flintlock primed, and the action reversed to seal the breech. The weapon was then ready to fire.

|

|

| [Drawings from material provided by Narragansett Armes, Ltd. for their replica Ferguson Rifle, permission to use received.] |

Captain "Pattie" Ferguson personally gave a stunning demonstration of his new gun at Woolwich Arsenal on April 27th, 1776 during rain and high wind. The weather would have rendered any Brown Bess useless even if the starting range hadn't been an unheard-of 200 yards (180 m). His personal weapon was hand-built and fitted with sights so he could showcase his marksmanship; the mass-produced ones were less accurate but still impressive. With the first 100 Ferguson rifles, he formed up and trained his Light Company, which went on to make history in the American Revolution during Brandywine and other battles.1 His loyalty to the men in the units he commanded led him to Drakia, after Ferguson's Legion was forced to abide by the terms of the Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolution and gave America independence. He rose to Colonel-General and General of the Militia in Drakia, but the rifle he invented as a young man in Scotland is his most enduring legacy.

A higher rate of fire than the other types was possible with the Ferguson, but the fouling problem was at least as bad as the other guns, so problems arose quicker in battle. After the third volley, about one quarter of a group of Brown Bess muskets would be out of action while the soldiers cleaned them. With a similar failure rate, a group of Fergusons would be useless as firearms in less than a minute. So the first Ferguson design was slightly modified after problems of this nature arose in early training and battles, but fouling would plague this and all other black powder guns for generations to come. Design changes validated by battlefield experience increased the weight from an estimated 3.25 kg for the first production in England (1776) to about 4.25 kg for those built in Drakia ten years later, but made for a much more reliable battlefield firearm. Even so, men using Fergusons soon learned to keep water at hand to help keep fouling down; in dry conditions it could quickly render the gun useless. In this one respect, the cloth patch used by muzzle loaders was a saving grace.

The Ferguson rifle — "the gun that broke the tribes" — had all the advantages of Brown Bess and the Kentucky rifle, with features uniquely its own. Unlike the Kentucky rifle, it could carry a bayonet, a factor of some importance in the 18th century, and unlike Brown Bess the "sticker" did not interfere with loading. Not only was its rate of fire substantially better than the smoothbore, but it could be loaded comfortably while in the saddle or lying down behind cover. The threaded plug gave excellent gas sealing, and Ferguson had improved on his inspiration, a system patented about 50 years earlier by LaChaumette, by designing recesses for fouling to accumulate instead of in the threads. A lighter bullet than Brown Bess meant that more ammunition could be carried. Unlike muzzle-loaders, it could not be multiply loaded by mistake in the confusion and noise of battle. These advantages also didn't press the limits of the rather primitive gunsmithing technology of the period; the plug had to be turned on a lathe, but this was the only unorthodox part.

In Europe and America, military conservatism kept the Ferguson rifle confined to specialist units if it was used at all. The British army was satisfied with its volley-and-bayonet tactics, their French enemies never showed any signs of initiating an arms race, and the Americans preferred smoothbores and the vastly inferior Hall breechloader for reasons of national pride and lack of competition.

The Drakians could not afford such luxuries. Faced by native opponents capable of fielding armies of tens of thousands of fanatically brave spearmen, they needed a weapon that could hit hard, fast, and far. Armories were soon established, employing skilled gunsmiths from the Loyalist population and later immigrants. Within 3 years of Ferguson's arrival, enough Ferguson breech-loaders were produced to equip the entire Militia. Drawing on the experience of the Dutch colonists before them, the new masters of the Cape rapidly formed units of mounted riflemen, supplemented by fast-moving horse-drawn light artillery. By the late 1780s, the Drakian militiaman of the early conquest had taken on the characteristics that were to last for most of the next fifty years: mounted on a small hardy pony and leading a string of remounts, equipped with a Ferguson, two double-barreled pistols, knife, and saber. Regiments of black slave-soldiers filled garrison and infantry roles once the systems of recruitment and training were perfected. A few dozen colonists with Fergusons were a match for regiments of black spearmen. Fighting from mobile wagon-forts, a few hundred militia could shoot down thousands without loss to themselves. And luckily for the Drakians, the hundreds of tribes that initially inhabited the region2 never formed the large confederations that might have successfully repelled the relatively small number of invaders. Instead, the tribes persisted in squabbling between themselves or making and then breaking coalitions of no more than several tribes each, driven more by mutual distrust and long-standing feuds than interest in group survival. Given a slower expansion from the Cape, a less effective weapon, or a leader able to unite more than 20 thousand or so men into a cohesive force, the tribes might have put up more successful resistance. But it was not to be.

The Ferguson was a weapon of revolutionary importance, yet it was by no means perfect. For example, the hot gases eventually eroded the seal between the threads of the plug and the drilled breech, requiring a new plug and re-machining. It required careful maintenance to prevent a buildup of fouling in the chamber and barrel, and the plug had to be wiped and oiled after every use to prevent corrosion, which could ruin the gas seal. Prolonged heavy firing could heat the chamber and cause disastrous "cook off" detonation of the loose black powder during loading. Like all flintlocks, it had a tendency to misfire, which required a lengthy and frustrating drill to clear the touchhole. Furthermore, the round ball used was very inefficient aerodynamically, limiting range and accuracy. Some of these were addressed with extra parts carried by the soldiers, others by careful discipline. But the last was a physical limitation that could actually be fixed, although aerodynamics wasn't even a practical science at the time.

The first important improvement to the Ferguson was the McGregor bullet. Captain Angus McGregor, a North Carolina Loyalist of Scottish background, had been using an heirloom "stonebow" (a crossbow adapted to throw small stones or lead bullets) to hunt duck on his estate near Virconium. It occurred to him that the same force from the crossbow's spring threw a pointed quarrel much further and more accurately than a round stone. Through much practical experimentation, he arrived at a significant improvement from the round ball, although it would take the advancement of science decades to quantify and explain what he could demonstrate. In 1792 he patented a "cylindro-conic" bullet, a short blunt-headed round with a hollow pointed head. McGregor had anticipated the effect of reduced air resistance, but not the even more important reduction of cross-sectional diameter in relation to total weight. Range was increased to over 500 meters against individual man-sized targets, and 900 against massed formations. The hollowpoint round also had much greater wounding power than the round ball. The colonial forces were rapidly converted, since the only modification necessary was a new type of bullet mold. Performance was altered as follows:

| Ferguson Rifle (with McGregor bullet) | |

| Caliber: | 11.43 mm (.45 inch) |

| Weight: | 4.25 kg |

| Range: | 450–550 m effective, 900 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 3–6 rounds per minute |

| Operation: | Lever-operated screw plug, breech loading |

This was the rifle and bullet that the Drakian Expeditionary Force took north to Egypt in late 1803. Egypt, formally part of the Ottoman Empire, had been occupied late in 1801 by a French army of approximately 15,000. They were originally under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte, but he had returned to France in early 1802. At the Battle of the Nile Delta in November of 1803, 6,000 Drakians (mostly Janissary slave-soldiers) faced 9,000 French troops under the command of Jacques Menou in a flat, sandy area immediately east of the irrigated zone. The Drakian infantry were deployed in a single-line formation, flanked by mounted rifles. The French attacked in company and battalion columns, relying on shock action, and were preceded by skirmishers. The Drakians opened volley-fire at 400 yards (365 meters), firing by tetrarchies [platoons]. None of the French formations came closer than 125 meters to the Drakian line, and only a few of the skirmishers were even able to open fire. The French columns broke and reformed for the charge several times, eventually suffering casualties of up to 75%. The crews of the French field-artillery were practically annihilated before they discovered that the Ferguson rifles outranged their fieldpieces.

The battle had begun just after dawn. Less than 5 hours later, the French were in full flight, pursued by the Drakian mounted infantry. Less than 200 of this French army ever returned to Europe. Drakian casualties were less than 150, of whom only 30 were free citizens. Oddly, this shattering demonstration of the superiority of the breech-loading rifle over the muzzle-loading smoothbore had little impact on the course of the war in Europe. The Egyptian theater was remote, and little attention was paid to it; the details were simply not known. Furthermore, the contending powers in the Napoleonic Wars were stretched to the limits of their manufacturing and logistical capabilities, supporting larger armies than Europe had ever known before. The British did equip some of their specialist light infantry regiments (the Royal Greenjackets, for example) with Drakian-made Fergusons. And the French, towards the end, issued the superior brass-cartridge Pauly-type rifles to their equivalents. But in the postwar cutbacks, the pace of innovation became even slower.

The penultimate refinement of the Ferguson rifle was the adoption of percussion ignition in 1804; a copper cap containing fulminate of mercury was used. The inventor—a sporting Anglican clergyman by the name of Alexander J. Forsyth—had been bothered by the delay between pulling the trigger and ignition in flintlock weapons, which made wing-shooting birds difficult.3 Percussion caps proved useful in military applications because they were immune to damp (unlike the priming powder in flintlocks) and because they were much less likely to misfire — one in several hundred rounds rather than the one in twenty typical for flintlocks. The improvement in rate of fire was minuscule, but that in reliability was significant. However, nearly all the weapons of the time that could be converted, were, so there was no net gain by the Ferguson compared to other contemporary weapons.

The war faction in the British Parliament succeeded in hanging on to Greater Egypt, despite demands from the Ottoman Empire to return what France had conquered. The result was war between the British and Ottoman empires in 1807. By withdrawing many of the British forces from Spain, they were able to seize Cyprus, Crete, Rhodes and Tunis while retaining Egypt. However, most of these were lost as the situation in Spain deteriorated without British manpower, and the final tally was the addition of Cyprus and Tunis only. The Congress of Vienna in 1815 confirmed these transfers, and the Ottoman Empire finally renounced its territorial claims in North Africa in favor of Britain, in return for 1,000,000 British pounds in gold (essentially paid by the Drakians) and several large loans. This conflict was notable only in that it didn't involve the Drakians. We can only speculate on what might have happened if they, instead of British troops drawn from Spain, had fought the Ottomans over 100 years earlier than in history. Instead, feeling snubbed by London's proper refusal to grant Drakia in southern Africa any power over Greater Egypt (the length of a continent away), the Drakian Militia rampaged through the nominally French territories near the Equator, and provided nearly all the infantry and cavalry troops for the seizure of Ceylon from the Dutch allies of France. These territories were thus under more Drakian influence than Greater Egypt was, making them the first territorial acquisitions of the Free Republic of Draka little more than 20 years later.

The final refinement of the Ferguson was again the design of the bullet. It came this time from an unlikely source, a militia quartermaster trying to save on the expense of lead. Joshua Nicholson was a frugal, detail-oriented man in charge of supplies for a Drakian Militia regiment deployed in Katanga [Angola] during both the encroachment into Portuguese territory and the pacification after the 1810 purchase. Hated by some of the troops for his parsimony, he started altering the bullet molds used by the troops so they used less lead per bullet. He thus independently developed an enlarged cavity in the nose of the bullet, grooves around the base of the bullet, and a cavity in the base of the bullet. Surprisingly, this worked up to a point. Nicholson had hit upon the ability of the powder charge to expand into the cavity, pressing the sides of the bullet into the rifling and imparting more consistent spin, thus increasing accuracy and range. Minor "hollow point" changes also increased wounding power, although this was difficult to quantify like range. Importantly for Nicholson, failed experimental bullets could be retrieved and recast; he was always more concerned about the cost of lead than the manpower, fuel (for casting) and powder. Several forays into iron or wood inserts in the cavity led to little improvement for increased complexity and cost, and were abandoned. After several years of practical, incremental work with immediate feedback from the troops, the Nicholson bullet was presented to the Militia Commander and quickly adopted throughout the force in 1814. Like the McGregor bullet, it was just a different bullet mold, but the Ferguson's performance now became:

| Ferguson Rifle (with Nicholson bullet) | |

| Caliber: | 11.43 mm (.45 inch) |

| Weight: | 4.25 kg |

| Range: | 500–600 m effective, 1000 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 3–6 rounds per minute |

| Operation: | Lever-operated screw plug, breech loading |

Although the Nicholson bullet was an improvement, the greatest gain from this innovation was realized for rifled muzzle-loaders. In those, the hollow base allowed the bullet to be small enough to drop easily down the barrel, like the original musket ball in a smoothbore, and then expand after the charge was fired to better grip the rifling. In a breech-loader, this is superfluous since the bullet can engage the lands in the rifling directly without having to pass cleanly by them during loading. Others elsewhere did appreciate the principle though, and followed up on Nicholson's work after the Napoleonic Wars to create various hollow-base designs for the muzzle-loaders still commonly used in Europe. The greater range and wounding power of those bullets soon forced changes in tactics, so the Drakans only stole a short march on the rest of the world.

From 1812–1816 a French inventor, Samuel Jean Pauly, had worked on the problem of breech-loading rifles. His solution was a cartridge case with a brass base that would expand to seal the breech, then contract when the gas pressure in the barrel fell after the bullet left the muzzle. This was an almost perfect solution—the one used for virtually every small arm from the 1850s on—but rather ahead of its time. In particular, seamless drawn-brass tubing was too expensive and its quality too unreliable at the time for anything other than small numbers of specialists. Pauly also invented a centerfire primer, a percussion cap set into the center of the rear end of his cartridge. He lived and died in France, apart from a brief visit to England to register a patent. However, his work inspired two disciples: Johann Nikolaus von Dreyse and Francois Telliard (b. Lyon, France, 1772, d. Kenia Province, Free Republic of Draka, 1842). It is the tale of these two, particularly Telliard, that now concerns us.

Dreyse's 'needle gun' took a unique path of development, culminating in acceptance by the Prussian Army as the 'Model 1841', the first breech-loader to achieve general issue by a European power. It is mentioned here solely to contrast it with the R-2 described further below. An amplified treatment of it, and how it enabled Prussia's ascendancy in spite of inherent design flaws and lagging tactics development, is in a later chapter of this work.

| Dreyse Model 1841 Needle Rifle (Zündnadel-gewehr) | |

| Caliber: | 15 mm |

| Weight: | 4.5 kg |

| Range: | 725 m effective, 900 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 10–12 rounds per minute (doctrinal limit 5) |

| Operation: | Breech loading with cylinder bolt, friction-combustible priming in middle of paper cartridge pierced by darting needle (zünd nadel) |

Telliard was frustrated by the lack of official support for mechanical innovation in postwar France. He expressed this loudly, and often enough, that he came to the attention of a disgruntled fringe group who were heading for Drakia on the basis of tales returned to France. There had been some French immigration to Drakia in the 1790s. These were almost entirely aristocrats dispossessed by the Revolution or refugees from the slave uprising in Santo Domingo. Many of the latter settled on the sugar coast of Natalia. Few of either group ever returned to France, but news of how they had prospered in this British-ruled land did. After the restoration of the Bourbons, there was another wave of French settlers, this time largely to Egypt and the incompletely pacified North African territories, consisting mainly of Napoleonic veterans and their families discontented with a drab peacetime existence or ruined by the fall of Napoleon's Empire. A few made the longer journey to Drakia, among them Telliard.

Francois first settled in Diskarapur, in 1816. At that time it was a rapidly-expanding center of iron and steel production, some of which was immediately sent on to local machinery and armaments manufactories. Employed as an "overlooker" in a factory manufacturing Ferguson rifles, he took advantage of the Ferrous Metals Combine's policy of making facilities available for after-hours experiments by its technical staff. (Diskarapur's free population at this time was only 3,000 or so, and matters were more informal than they later became.)

Judging from his surviving notes and drawings, Telliard attacked the problem of improving on the Ferguson rifle from two angles. The first was to eliminate the separation between primer and charge (loading the round and placing the cap on the vent), and the second was to find a method of breech sealing better than Ferguson's screw-plug.

The solution had the simplicity of genius. Telliard designed a single-piece cartridge, consisting of three elements. First was a rather long, pointed bullet. This was set firmly into a tube of stiffened gauze soaked in nitrate. The tube was then filled with a dough of moistened gunpowder, and a percussion cap set in a cardboard disk was placed over the open rear of the tube. Carefully dried, the round then contained primer, propellant, and projectile in one piece, was strong enough to be handled, and was reasonably water-resistant after shellac was applied to the exterior.

The loading and sealing mechanism was equally simple. A turn-bolt system was used, shaped exactly like a door-bolt. To load, the bolt was turned up (unseating a locking lug at the head of the bolt, immediately behind the chamber) and withdrawn. This motion compressed the spring within the bolt and readied the firing pin. A round was then thumbed into the chamber, and the bolt driven forward and turned down to lock firmly behind the cartridge. When the trigger was pulled, the firing pin shot forward and struck the percussion cap.

This left the problem of sealing the breech against the escape of gas. Experiment proved that a metal-to-metal seal eroded quickly. Telliard then thought of Pauly's solution. Individual brass cases were currently impractical, but Telliard developed an alternative. A short brass tube was made, open at both ends. Halfway along it, a metal disk was placed, completely blocking the tube except for a hole in the center exactly the size of the firing pin. One end of the tube was threaded, and screwed onto the head of the rifle's bolt. The other (very slightly smaller in diameter than the inner end of the rifle's chamber) was open. When the bolt was pushed forward, the open end of the tube cradled the base of the cartridge. Upon firing, the hot gases pressed against the inside of the tube, expanding it to firmly grip the walls of the chamber with a gastight seal. When the bullet left the muzzle and the pressure dropped, the elastic brass contracted, the bolt was turned and withdrawn, and the whole cycle begun again. Together with careful redesign of the bullet to take advantage of principles discovered by McGregor, Nicholson and others elsewhere, the results were as follows:

| Telliard–Pauly Rifle (R-2) | |

| Caliber: | 11.43 mm (.45 inch) |

| Weight: | 4.5 kg |

| Range: | 725–900 m effective, 1350 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 8–10 rounds per minute |

| Operation: | Turn-bolt with obturator ring |

This advance in small arms wasn't immediately accepted by the Drakians, regardless of the advantages it had over the now-venerable Ferguson. At the time Telliard created workable prototypes, the British Army in Drakia was attempting to reduce the influence of the Drakian Militia. One step towards this was trying to discourage the local procurement of ammunition and weapons, as the Militia and Army had no commonality, but London still wasn't interested in switching the entire Army from the Tower musket to the Ferguson. A farcical sequence of orders were issued to the Drakian Militia by the Army, ordering them to disband or accept the Army's obsolete weapons. In the end, the Governor intervened, and the only use the Militia ever made of the muskets was in several parades. This delayed the Militia from even considering new weapons for several years. The growing concern in London over Drakia's expansion, entirely due to Militia action or even less formal groups of armed free citizens, also fostered a smaller scale of operations from about 1815 to 1821. Late in 1821, Telliard was finally able to persuade the Drakian Militia to make their own comparison of his work against the most recent version of the Ferguson. After demonstrating clear superiority over the Ferguson in a "shoot-off," the Commander authorized issue of the Telliard rifle, designating it the R-2; the Ferguson was never actually designated the R-1, but the Militia didn't want to ignore what had brought them to this point. While the Army objected again, the officers involved became caught up in a power play by the Governor, and were soon transferred to North Africa. The cadre from Drakia that objected to the non-standard weapons used by the Militia soon found themselves petitioning (with only partial success) the Army for those same weapons to better face the Berbers and Arabs. Even after losing significant portions of North America in the War of 1812 to American militia equipped with Kentucky rifles and Hall breechloaders, the British Army and government remained violently conservative. All that the Army did is continue to phase out the Brown Bess in favor of the Baker rifle, which still used a spherical ball.

As new members of Militia units began bringing the R-2 rifles out into the field, demand accelerated from the old hands who quickly recognized its advantages. But the R-2 design had its own problems: the cartridges required moderately careful handling, very rapid fire could produce "cook-off," and the machining required for mass production of the weapon was near the limits of available technology (particularly by slave labor). After several hundred firings, the brass cup would become brittle and inelastic. It then had to be unscrewed (with a special wrench kept in a compartment beneath the buttplate of the rifle) and replaced. The advantages were so overwhelming, however, that by the late 1820s the Drakan armed forces were completely reequipped with the new weapon.

Telliard himself was granted a commendation, 50,000 aurics prize-money, and a 4,000-acre plantation in the newly-seized Madagascar Province. He had a further productive decade, during which he developed the world's first practical revolver and was instrumental in organizing the Diskarapur Technological Institute. He then retired to his estate to breed horses and experiment with viticulture.4

After the adoption of the Telliard–Pauly rifle, the Drakans made only minor improvements in the next 25 years. The R-2 was certainly superior to the British Army's weapons during the Draka Rebellion of 1834–36, but it wasn't the only advantage the Drakans had. However, there are many tales of Army units killed nearly to a man by the longer-ranged R-2 in the hands of the Militia or Janissaries during this time.

Once the British Empire recognized the Free Republic of Draka (FRD), and internal consolidation was completed, the Drakans again found themselves in need of local sources of improved weapons. The British officially accepted the accomplishment of the Draka Rebellion, but they spent much of the next decade building the Suez Canal and arranging boycotts to punish the FRD. These external conditions, and a need for more firepower to suppress internal unrest, led to further innovation in small arms.

The next technical breakthrough proceeded from the development in the 1840s of techniques for cheap mass-production of seamless brass tubing. This was the result of improvements in automotive steam engines, but had a military application. East and Central Africa were being conquered, and the hot wet climate was having unfortunate effects on the permeable cartridge of the R-2. Also, attempts to design a workable repeating rifle had broken down on the fragility of the R-2's ammunition, and the burgeoning internal security needs were becoming acute. A drawn-brass cartridge was perfected in 1847, and the opportunity was taken to further reduce the caliber of the weapon. The feed mechanism was a steel box beneath the bolt, holding eight rounds and with a Z-shaped spring attached to a riser plate beneath the ammunition. Moving forward, the bolt "stripped" a round out of the lips of the magazine and chambered it. After firing, the bolt was turned, grasping the cartridge with a wedge-shaped extractor on the bolt face and withdrawn. As the bolt withdrew, so did the empty cartridge case, striking a milled "shoulder" and being flung out of the rifle. With the bolt left back, the magazine was exposed and could be reloaded, initially with individual rounds and later with clips of four, and finally eight, rounds in a beveled zinc strip holder. The new R-3's performance was as follows:

| R-3 Rifle | |

| Caliber: | 10.16 mm (.40 inch) |

| Weight: | 4.3 kg |

| Range: | 900 m effective, 1350 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 10–12 rounds per minute |

| Feed System: | Fixed box, 8 rounds |

| Operation: | Turn-bolt |

The R-3 proved its worth both in the conquest of the remainder of "unclaimed" Africa, primarily Sudan and Ethiopia, and the numerous incidents of unrest that it quelled in the hands of the Security Directorate. With the R-3, the black-powder rifle had reached the ultimate refinement. The disposable cartridge helped to reduce the heating problems endemic to earlier types, removed much of the fouling from the chamber of the rifle, and was also virtually unaffected by water. The only remaining serious problems were those inherent in the black-powder propellant: fouling of the barrel, the required frequent cleaning (difficult in the heat of battle), and the large output of smoke which disclosed the firer's position and could blanket an entire battlefield. Further improvements in firepower would require advances from two separate portions of the Industrial Revolution: advanced chemistry and the repeatable (and interchangeable) action of precision machinery.

Frederick James Gatling (b. 1818, Maney's Neck, North Carolina; d. 1905, Archona, Archona Province) was a Southern-born inventor who began producing at an early age. His first career was in the field of agricultural machinery; his seed drills were ingenious and widely used. His second began in the late 1840s, when he developed the first version of the ten-barreled crank-operated machine-gun that later made his name famous. Gatling failed to interest the American government in his invention; the head of the Bureau of Ordnance was interested in more accurate weapons rather than ones that sprayed large numbers of bullets. So Gatling went to London in the spring of 1850 to test the European waters. He found little interest there too, but happened to meet (in a City chop-house) a junior member of the Drakan embassy, Marius de Witt, who had worked in the Naysmith Machine Tool Combine's design section in Diskarapur.

De Witt interested his superiors in Gatling's designs, and Frederick was encouraged to move to Diskarapur. There, in cooperation with the engineers from the Naysmith and Ferrous Metals Combines, he quickly perfected his designs. The new metallic cartridge proved ideal for this use, and a reliable weapon with a rate of fire in excess of 600 rounds per minute was quickly produced. General issue to the Drakan armed forces began in 1855, and Gatling guns were used with devastating effect in quelling several serf revolts. However, the Gatling was definitely a "crew-served" weapon comparable to small field artillery, and improvements in more portable (i.e. small arms) sources of firepower were still needed.

The first international visibility of the R-3 came, oddly enough, in America's Slaver Exodus. While relations with the USA had always been rather chilly, many Drakans had family ties with the Southern states. There were also ideological links, strengthened in the 1830–1860 period as both the South and proto-Domination became conscious of their isolation in an increasingly bourgeois world. Accordingly, when the transcontinental railroad deal to compensate slave owners was announced, Draka was interested. As the terms became public, the FRD found it in their own best interest to encourage plantation owners to accept the terms, even sell out early, and immigrate to Draka. The fleet of armed luxury steamships that began arriving in southern US ports in December 1861 to take away fleeing former slave owners also carried contingents of Drakan troops armed with R-3 rifles, and many more in storage.

The American armed forces of the day were armed with the Hall–Springfield rifle, a percussion-cap, single-shot breechloader with a lever action sealed by a Telliard-style brass obturator. Cheap, simple, rugged and easy to maintain, this was an excellent weapon of its type, and nearly everyone in the country — Army and Militia alike — used it. Resupply was thus very easy, and one of the reasons why a general civil war didn't break out was that everyone was identically armed. Thus there was no clear advantage in weaponry, and the common education of officers by West Point cadre meant leadership was similar across the nation. The R-3 rifles brought over by the Drakans were used on several occasions to repel mobs assaulting Drakan ships in southern ports, and in the few "rescue expeditions" mounted into the interior to collect besieged slave owners. The R-3 in the hands of Drakan soldiers (and a few re-armed former slave owners) made a great impression on the relatively unorganized poor whites and untrained freed slaves that opposed them. "Slaver's Eight-Tail" is one of the more printable nicknames given to the R-3. The anarchic situation never had any organized fighting between the US Army or recognized Militia units and the Draka, but the Draka (nearly all Citizens rather than Janissaries) usually got the better of the engagements. The Draka were mindful that clashes with organized US forces could easily cause the US government to officially notice their illegal presence in the South, and war was not in their interest. Several Gatling guns were also used by the Draka, and cast steel artillery mounted on the ships, but these had limited visibility in the chaos of this period. This incursion by the Draka "rescuers" marked the last time that an armed hostile force successfully operated against US citizens at home. By late 1862, the Draka had departed. All told, their ships carried over 200,000 former slave owners, their families, and sympathizers to a new home in Africa. They left behind a ravaged southern countryside torn by class and race hatred, and a northern economy about to collapse as credit tightened to inconceivable levels and land speculation wildly swung back and forth. Only a true civil war between the "free" and "slave" states, to finally break the Great Compromise in bloody fighting between organized armies, could have been worse, and could have easily ignited a wider conflict if Draka and Britain had gotten involved.

At this point, a digression from the "long" rifle to the shorter pistol form is in order. While the Ferguson, R-2 and R-3 were important and useful long-range weapons for the individual, there were also shorter-range needs. The bayonet and saber mentioned earlier fulfilled the hand-to-hand roles, but there was a middle ground as well. Taking a cue from pirates of the high seas and officers of European armies, many freemen in the Drakian Militia, and later all the Drakan Citizens, carried sidearms in the field. These initially were single-shot black powder pistols, then double-barreled. When the revolver was developed by Francois Telliard and refined by others, the Drakans were among the first to seize upon it for military and internal security issue.

One noteworthy sidearm indigenous to Draka dates from just after the Slaver Exodus, inspired by the chaos that occurred in the port of New Orleans. The primary inventor, Dr. Jean-Claude Le Matt, fled New Orleans in the last Draka ship after news circulated that he had treated some wounded "slavers", and his house was burned by a mob of frustrated poor whites. He lost several family members in the escape, which included the use of a concealed shotgun. He ended up in the sugar country near Virconium, and devoted himself to developing a combination pistol and single-shot shotgun weapon as a sort of revenge. In its final form (the Model 1870), it had a swing-out cylinder, and was the last black powder sidearm authorized for regular use by Drakans. Note that the word "issue" wasn't used; these weapons were contracted for directly with Le Matt or one of his agents, and available with a variety of levels of decoration. Some that went into battle with less-affluent Citizens were "no frills", but most were works of deadly functional art in engraved steel, turquoise and ivory. Most of those that exist today are highly prized Drakan family heirlooms that are lovingly maintained; there were at least two duels fought using Model 1870s in the past decade.

The revolver portion of the Le Matt Revolver initially fulfilled a Drakan standing requirement for a multi-shot cavalry sidearm. However, as Le Matt wasn't an experienced gunsmith, just a gifted amateur, the caliber of the first model was .36 (9.14 mm), not one of the standard ones (.35 or .40) already used by the Draka. Le Matt was prevailed upon to alter the weapon's bore to .40, an existing rifle caliber, even though accuracy suffered from using ammunition designed for a much longer barrel. It was at this juncture that he thought to use the "waste" space in the center of the revolver's cylinder, and installed the single-shot buckshot barrel that made the weapon unique. In the heat of battle, men able to take advantage of this area effect often found it caused more casualties than the revolver's six to nine (depending on model) shots. While making the weapon even more mechanically complex, this unexpected (to the ignorant) capability gave the bearers of the Le Matt a very short range "equalizer" that could come in extremely handy in the confused melee of a cavalry action.

During the evolution of Le Matt's design, the caliber of both the revolver and shotgun changed several times, as did the number of shots. Important innovations such as a thumb lever to switch from revolver to shotgun, and a better retention mechanism for the loading rod, also had a checkered history. However, it is with the Model 1870 that Le Matt finally achieved the effectiveness he had been searching for:

| Le Matt Revolver, model 1870 | |

| Caliber: | 12.12 mm (.477) centerfire, 16.26 mm (.64) shotgun |

| Weight: | 1.6 kg |

| Range: | 25m effective, 40 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 15–25 rounds per minute (revolver) |

| Feed System: | 6 round revolver, single buckshot cartridge |

| Operation: | Swing-out cylinder |

Mining had always been an important part of the Drakan economy, and when the Swede Alfred Huskqvist (b. 1820, Uppsala, d. 1890, Kenia Province)5 perfected his method of stabilizing nitroglycerin by absorption, it was quickly adopted as the main explosive in the mines of the FRD. Dynamite (as the new compound was called) exploded far too readily to be used as a propellant, but proved to be very suitable as a bursting-charge in artillery shells. After settling in the FRD, Huskqvist developed a mixture of nitroglycerin and nitrocellulose that could be extruded into various shapes, and which gave a much more controlled "burn" than black powder. The new compound was patented in 1872, and known variously as "cordite" (from the string-shaped pieces initially used), "white powder" (from its color) and, usually, "smokeless" powder. The War Directorate immediately noted the superiority of the new propellant: less fouling to build up in the chamber and barrel, much less smoke to give away the rifleman's position, higher velocity, and flatter trajectory. At first, double-base smokeless powder was substituted for the original 250-grain load of compressed black powder used in the R-3. However, this meant the breech had to be strengthened to handle the higher pressures, and the sights redesigned for longer ranges. What resulted was a modified R-3 rifle that was entered into a testing program as the R-X-4; this was intended to be a modification kit to the R-3. Performance was as follows:

| R-X-4 Rifle | |

| Caliber: | 10.16 mm (.40 inch) |

| Weight: | 4.4 kg |

| Range: | 1350 m effective, 2000 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 10–12 rounds per minute (reloaded) |

| Feed System: | Fixed box, 8 rounds |

| Operation: | Turn-bolt |

However, there were serious problems, and the R-X-4 was withdrawn from testing before ever being issued. Only a few were ever produced, and none issued to field units; the design museum at the Technological Institute of Archona is the only location where these can be found in the present day. Recoil was excessive, and the velocity so high that the bullet tended to melt in the barrel, lining it with smears of lead. The rifling also tended to "strip" the exterior of the bullet.

This failure was taken as an opportunity to redesign the service rifle from the ground up. A smaller caliber was used, since it was obvious that the higher velocity reduced the need for a large bullet to achieve severe wounds. The shape of the bullet was redesigned with a "boat-tail" to reduce drag, which extended range even further. The round itself was made of lead swaged into a jacket of harder alloy, except for the nose, which was left bare to expand inside the target. And the feed mechanism was altered to a detachable clip with 10 rounds, which made reloading easier under battlefield conditions. Designated R-X-4a while under development, this weapon entered service as the R-4a.

| R-4a Rifle | |

| Caliber: | 7.5 x 60 mm |

| Weight: | 4.1 kg |

| Range: | 1825 m effective, 2275 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 12–14 rounds per minute (reloaded) |

| Feed System: | Detachable box, 10 rounds |

| Operation: | Turn-bolt |

The R-4a was standard issue for the Drakan armed forces until 1906, with the advantages of simplicity, light weight, rugged construction, and a very hard-hitting round. While the only wartime use was by Citizens during the final conquest of Ethiopia, it served well. The R-4a had several imitators in Europe, e.g. the German Mausers of 1888 and 1898.

While the Gatling gave excellent service, it was inevitably large, bulky, heavy, and usually mounted on a modified field-gun carriage or steel tripod. In vehicle mounts with an exterior power source, the very high rate of fire and reliability made it nearly ideal, but for infantry service it had severe limitations.

After the adoption of smokeless powder, the Drakan Gatlings were easily modified to fire the new round, but it was obvious that new possibilities were opened by the new propellant — especially by its reduced waste residue and the more efficient "long push" that its slower burn gave as compared to black powder.

The first new application was in a heavier weapon, a 25 mm automatic cannon designed for armored-vehicle use and as an antiairship defense. Developed by Charles Manson of the Army Technical Section in 1882–86, it used a form of blowback operation, combined with advanced primer ignition. The breechblock was flanked by two metal arms, themselves attached to a strong coil spring in a sheath around the lower barrel of the weapon. When released, the block was pulled forward by the spring, stripping a shell out of the metal-link feed belt and firing it slightly before reaching the full-forward position. The recoil force thus had to stop the forward inertia of the breech, then move it backward against the mass of the breechblock, the two flanking arms, and the force of the coil spring.

While efficient, the mechanism was not directly transferable to small arms. It did inspire a good deal of experimentation, and in 1890 Dr. Alexandra Tolgren, of the Shahnapur Technological Institute, made the first serious application of the gas-delayed blowback principle which was to be the foundation of Drakan small-arms design for two generations.

The Tolgren automatic pistol used a rimless modification of the standard 10 x 15 mm smokeless-powder pistol round adopted in 1881. The feed device was a 12-round staggered box clip in the grip. Operation was as follows: the bolt, which was machined to wrap around the barrel on three sides, ran forward, chambered a round and fired when the trigger was pulled. Above the barrel was a short cylinder, the rear end of which was sealed. A gas port was drilled through to the barrel, and a piston-head and rod were inserted in the tube forward of the port. The operating rod ran forward through a further, slotted portion of the tube which contained a coil-spring, and at the forward end was fastened to two steel pins that ran in grooves back along the outside of the gas tube and attached to the bolt.

At rest, the spring held the breech sealed. When fired, the recoil of the weapon began to blow the bolt backward, against the force of the coil spring and the inertia of the bolt and operating rods. These alone would not have sufficed to keep the breech sealed, but as the bullet fired, high-pressure gas filled the tube above the barrel and prevented the piston head from recoiling. Once the bullet had left the muzzle, the pressure in the cylinder dropped and the piston traveled backwards, forcing the remaining gas into the barrel. The bolt recoiled, then moved forward as the coil spring expanded, stripping another round from the clip and repeating the cycle.

The gas-delayed blowback system proved to give a reliable operation, particularly after it became possible to chrome-plate internal parts subject to gas-wash.

| Tolgren Automatic Pistol, model 1890 | |

| Caliber: | 10 x 15 mm |

| Weight: | 1.2 kg |

| Range: | 45 m effective, 90 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 45 rounds per minute (reloaded) |

| Feed System: | Detachable box in grip, 12 rounds |

| Operation: | Gas-delayed blowback, semi-automatic |

In 1893 a design team from the Technical Section decided that the Tolgren action could be scaled-up to produce a "machine pistol" — a portable, automatic short-range weapon suitable for police and close-quarter military use.

| Machine Pistol Mk. I, model 1894 | |

| Caliber: | 10 x 15 mm |

| Weight: | 3.4 kg (with collapsible steel stock) |

| Range: | 135 m effective, 185 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 600 rounds per minute, theoretical |

| Feed System: | Detachable box in grip, 35 rounds (75-round snail drum for special roles) |

| Operation: | Gas-delayed blowback, selective fire |

This proved a great success — although somewhat over-elaborate, as European experience in the Great War showed that a simple blowback weapon with a heavier bolt would do quite satisfactorily. It should be noted that the Drakan armed forces initially found little role for the machine-pistol/submachine-gun, since current tactical doctrine envisaged infantry combat at greater ranges. The Domination's War Directorate issued it fairly extensively to personnel for whom a full-sized rifle was inconvenient: armored vehicle crews, gunners, and the female-only units stationed behind the front lines. The Security Directorate found it much more useful, and equipped about one third of their Order Police with it. No European power showed any interest until after the outbreak of the Great War in 1917.

The decision to develop a full-power semiautomatic rifle, based on the principles of the machine pistol, came in 1900. The Tolgren action was adopted; there was initially some doubt that a system without positive mechanical locking of the bolt could operate using a powerful full-bore rifle cartridge, but experiments proved the contrary. A notable feature was the semi-closed bolt; at rest, the bolt was set slightly back from the closed position. When the trigger was pulled, the firing pin struck the primer, and the bolt was simultaneously freed to complete its run forward; this absorbed a considerable share of the recoil and made it possible to build a very light action. The resulting weapon, adopted for general service in 1906, and standard issue until 1936, was the R-5:

| R-5 Rifle | |

| Caliber: | 7.5 x 60 mm |

| Weight: | 4.4 kg |

| Range: | 1825 m effective, 2275 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 25 rounds per minute (reloaded) |

| Feed System: | Detachable box, 15 rounds |

| Operation: | Gas-delayed blowback, semi-automatic |

The R-5 was produced in enormous quantity, over 11,000,000 being turned out during its period of general issue. No substantial modifications were made during this time, just minor alterations to simplify manufacture. The action worked very smoothly, and the advanced primer ignition and semi-elastic "gas cushion" effect of the delayed blowback gave minimal recoil. The result was a rifle that was very pleasant to fire, nearly as accurate as its bolt-action predecessor, and had twice the firepower. In fact, the R-5 proved to be another classic weapon, its only drawback being the extensive machining necessary for manufacture. In the field, it gave the Drakan infantry a density of firepower none of their opponents could match, particularly in combination with its companion piece, the Lochos Automatic Weapon Mark 1 (LAW-1).

The Technical Section team that designed the R-5 also saw an opportunity to develop the first really portable machine-gun. Simply modifying the trigger-mechanism of the R-5 gave an automatic weapon, but magazine capacity was too small, the barrel tended to catastrophic overheating (and attendant cook-off) and the weapon was violently unstable in full automatic mode. Modifications followed, first to fit a heavier barrel with a carrying handle and quick-change facility. The forestock of the rifle was replaced with a slotted metal guard and grip. A bipod was fitted to the gas-regulator, a straight-line butt and pistol grip was fitted, and the operating mechanism was made more robust. Finally, a pawl-and-ratchet belt-drive device was installed, with provision for quick conversion to magazine feed. The "Lochos Automatic Weapon, Mark I" could then take the standard disintegrating link belt feed (usually in 75-round belts packed in a box that clipped beneath the weapon), or 15 or 30-round box magazines inserted from the top. Specifications were as follows:

| Lochos Automatic Weapon, Mark I (LAW-1) model 1907 | |

| Caliber: | 7.5 x 60 mm |

| Weight: | 8.6 kg |

| Range: | 1825 m effective, 2275 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 600 rounds per minute, theoretical |

| Feed System: | Disintegrating-link metal belt / 15- or 30-round box |

| Operation: | Gas-delayed blowback, automatic |

With these two weapons the Domination fought the Great War of 1917–1922 and carried the drakon banner to Tangier, Alexandria, Constantinople and Teheran.

The Domination infantry lochos [squad] of the Great War was equipped with a mixture of LAW-1's, R-5's, and machine-pistols; subsidiary weapons included rifle grenades, hand grenades (stick and "egg" types), flamethrowers, heavier water-cooled machine guns, and light mortars. With the winding-down of the Pacification Wars in 1925–26, the Technical Section made a detailed analysis of the actual operation of these weapons in the field; the Drakan armed forces generally were anxious to avoid "victory disease" and self-criticism was being encouraged.

The R-5 had been very popular with the actual users, and was widely imitated in the postwar period, e.g. the American Springfield-7 (1927), the British Lee–Shallon (1922, almost a direct copy but coming too late to save Africa), the French MAS, the Russian Tokarev, etc. In fact, by 1939 the only major power not to convert to the full-power semiautomatic format was Germany. Designers there were advocating a subcaliber compromise weapon, but reparation payments and a vast stock of existing rifles guaranteed that development would be a low priority. Germany's rearmament with modern weapons in most areas during the 1930s was mostly due to being forced to start over after handing over nearly all of their clanks, machine guns and air force as war reparations. Even though the German study, like those done in all the other Great Powers between the wars, independently came to much the same conclusions, Germany was least able to implement the recommendations for infantry small arms before the next war started. The Drakans, trying to stay ahead, looked to their Pacification Wars and the lightning campaigns that had secured Africa and the Middle East, instead of the trenches of Europe.

Much to their own surprise, the Small Arms Study Project run by Sven Holbars of the new Alexandria Academy determined that the R-5 was far from an ideal weapon. The average range of infantry combat had decreased, even in open desert country, and all major combatants had adopted the Drakan/German system of dispersed infiltration infantry tactics. The full-power cartridge was superfluous at ranges within 800 meters, and 90% of all infantry engagements were at that or less. Beyond that range, crew-served weapons were more effective. Furthermore, the venerable 7.5 x 60 mm round made a true selective-fire rifle impossible; a weapon light enough to be useful was uncontrollable in full-automatic mode, and the barrel overheated disastrously.

The Project therefore decided to "reinvent the wheel" and design a new weapon from the ground up. Since the rifle was merely a delivery system for the true weapon — the bullet — ammunition was the first priority. The design parameters emphasized the smallest and lightest possible round which would have good wounding characteristics with the 800-meter envelope and would still punch through the average steel helmet at that range. A small-caliber, high-velocity round was found to give the best effective combination of characteristics (a caseless round would have been even better, but this proved extremely difficult). The caliber settled on was 5 mm, with a bottle-necked 45 mm cartridge case of aluminum alloy.

The gas-delayed blowback action of the R-5 and LAW-1 was used for the new rifle. The design was actually based more on the LAW-1 than the rifle, as automatic fire and an integral bipod were part of the specifications. The feed device was a matter of controversy; with the 600 rpm cyclic rate envisaged, a box clip was of doubtful use — it tended to become unmanageably bulky and unreliable with capacities over 34–40 rounds. A 75-round disintegrating-link belt, prepackaged in a conical drum, was settled on, using aluminum for the belt and feed lips of the drum, and the new glass-fiber resin for the box itself; the rear face was translucent so the soldier could see at a glance how many rounds were left. Performance was as follows:

| Holbars R-6 Assault Rifle, Model 1936 | |

| Caliber: | 5 x 45 mm |

| Weight: | 4.4 kg |

| Range: | 725 m effective, 900 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 600 rounds per minute (theoretical) |

| Feed System: | Disintegrating-link metal belt, 75 round drum |

| Operation: | Gas-delayed blowback, automatic; optional 3-round burst |

Careful engineering and extensive use of high-strength alloys reduced the loaded weight to less than 4.5 kg. Combined with the low recoil force and soft action, this made the Holbars fully controllable even when fired from the hip on full automatic. A bipod was attached below the gas port, and when not in use folded into a slot on the bottom of the laminated wooden foregrip. The stock was a metal frame, with a robust folding hinge; when collapsed, it lay along the left side of the weapon. There were post-and-aperture sights, but the main system was an optical x4 sight; this was optimized for quick use, and encased in a rubber-padded "shroud." Most troops carried their optical sights permanently clipped to the weapon, although they could be removed with the standard maintenance tools. Folded, the weapon was only 75 centimeters long, an important point given the increased use of armored personnel carriers. The Holbars was usually carried across the chest on an assault sling.

A companion LAW-2 was developed concurrently; this was very similar, but used a 150-round drum and had a heavier quick-change barrel attached to a carrying handle. This two-weapon combination was used throughout the Second Great War, and remained standard issue for the Domination's forces until the early 1970s.

With the Holbars, the metallic cartridge selective-fire rifle had reached the endpoint of its development. Minor detail improvements in materials and performance were possible, but any fundamental improvement required a complete redesign. The basic breakthrough was a successful caseless cartridge — in essence, a high-tech version of the old R-2. Research had begun as early as the 1920s, and continued for forty years in a desultory fashion. Apart from gas sealage (no longer a problem with modern machining) the primary difficulty had to do with ignition and heat-disposal. The metallic cartridge had served not only to seal the breech of the weapon but to carry off much of the heat of the combustion.

The final answer to the problem was to abandon the dual-base propellants that had been in use since the introduction of smokeless powder, and go over to an actual explosive — previous propellants had really been very fast burners rather than explosives proper. To keep chamber pressures within acceptable limits, the explosive was diluted with a combustible synthetic, which also acted as a matrix to provide mechanical strength for the round. The projectile, the bullet proper, was almost entirely enclosed in a rectangular block of propellant, greatly easing the design of magazines and eliminating waste space. Ignition was electrical (initially a battery with piezoelectric auxiliary, later using a superconductor storage cell), and the chemical mix was designed to be very resistant to heat and shock-wave detonation.

At the same time, the traditional stock-action-magazine-barrel design was abandoned, and the pistol grip was placed forward of the action. The buttplate was immediately behind the action (next to the user's face when the weapon was shouldered), which posed few problems since there was now no need to eject spent cartridges. The resulting R-7 entered field trials in the mid-1960s:

| Holbars R-7 Assault Rifle, Model 1971 | |

| Caliber: | 4.5 x 40 mm, prefragmented and other options |

| Weight: | 4.5 kg (5.7 with grenade launcher) |

| Range: | 725 m effective, 900 maximum |

| Rate of Fire: | 2000/600 rounds per minute (theoretical) |

| Feed System: | 100-round spiral cassette |

| Operation: | Recoil; optional 3-round burst |

| Notes: | Most R-7's incorporated a single-shot 35 mm grenade launcher below the main barrel. A grenade was loaded into a slot near the buttplate, with a selector switch above the trigger group to change from regular to launcher. |

Appeal to the readers: If somebody knowledgeable about guns can provide information for the OTL Dreyse "needle gun," the LeMat revolver, or even make up something for the Draka timeline's Telliard revolver, send it to me. You will be given credit in the document. The numbers I'm looking for are emphasized like this within the document.

Footnote 1: One of the Light Company shot and killed General Washington's aide-de-camp at Brandywine, as the recently arrived Polish cavalry officer appeared similar to a French Hussar, and was charging at their position. Ferguson's report of his unit's participation in the battle mentions that he himself had a Rebel General in his sights at one point, yet he forbore to shoot a gentleman in the back. The American Revolution would certainly have taken a turn away from history as we know it, if Washington had fallen to a Ferguson rifle. (back)

Footnote 2: Although the Drakians and Drakans thoroughly expunged nearly all of the southern African tribal societies out of existence, many artifacts survived as trophies. Careful analysis of these has led to estimates that as many as 950 distinct tribes existed south of the Zambesi River before the Drakians began their conquest. (back)

Footnote 3: Like Ferguson, another native of Aberdeenshire. The percussion cap also eliminated the bright white flash from the flintlock's pan that could disconcert an untrained shooter, or even alert the target. (back)

Footnote 4: His son, William Telliard, was the author of Ravens in a Morning Sky, the first notable Drakan novel, as well as other works. His granddaughter Cynthia Telliard played an instrumental part in the campaign for women's suffrage. (back)

Footnote 5: Huskqvist settled on a coffee plantation in Kenia Province, and the Huskqvist family have remained as Landholders on the estate ever since. His daughter, Karen Huskqvist, was the author of the noted Into Africa. (back)

Counter says: ![[a number only available as graphics]](http://visit.webhosting.yahoo.com/counter.gif) hits on this page since initialization.

hits on this page since initialization.

By Peter Karsanow.

The Draka characters and situations are copyright © S.M. Stirling and may not be used or reproduced commercially without permission. No profit is being made from the stories/documents/files found on this website.

Ferguson Rifle images are property of Narragansett Armes, Ltd., permission to use for this purpose received.

The Home page has overall site and copyright information.