1860 photo taken 4 days after Mr.

Lincoln visited Lincoln, Illinois, for the last time. Info at 3 below.

This President

grew;

His town does too.

Link to Lincoln:

Lincoln & Logan County Development Partnership

Site

Map

Testimonials

Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission of Lincoln, IL

|

Email a link to this page to someone who might be interested.

Internet Explorer is the only browser that shows this page the way it was

designed. Your computer's settings may alter the display.) April 24, 2004: Awarded "Best Web Site of the Year" by the Illinois State Historical

Society "superior

achievement: serves as a model for the profession and reaches a greater

public" |

|

Marquee Lights of the Lincoln Theatre, est. 1923, Lincoln, Illinois |

|

|

|

"The tragic sense doesn't grow on huckleberry trees. Or the ability to express it." -- William Maxwell, letter to native Lincolnite author Robert Wilson (October 31, 1977). Copy provided to Leigh Henson by Robert Wilson's daughter, author Sue Young Wilson. Social Consciousness in William Maxwell's Writings Based on Lincoln,

Illinois This Web

Page Is Dedicated to the Memory of Florence Molen,

Florence Molen

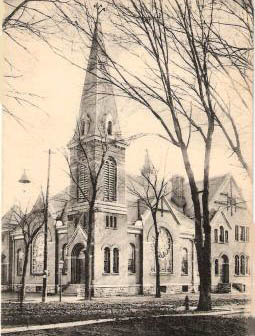

When I was a freshman at Lincoln College (1960-61), one day I happened to find myself walking down the stairwell of University Hall with my two English teachers: Ms. Lois Hall, whom I had for two semesters of composition, and Mrs. Florence Molen, whom I had for two semesters of introduction to literature. Ms. Hall had just broken a foot and had a large cast on. Mrs. Molen asked me what I thought of Ms. Hall's "ballet slipper" (leave it to English teachers to use clever figures of speech). Also, Mrs. Molen asked me if I had ever heard of William Maxwell. She told me he was from Lincoln, Illinois, worked at The New Yorker, and wrote about his hometown. I admitted I had never heard of him. I did not tell her that I doubted anyone could write literature about such a small town as Lincoln, Illinois. Mrs. Molen brought a great knowledge of literature to her teaching, but she was somewhat intimidating in her expectations. (She also taught adult Sunday school classes at the First Presbyterian Church, and my mother told me that Mrs. Molen's approach in those situations was also rather intimidating.) Perhaps the article summarized here somewhat atones for my youthful prejudice against Mr. Maxwell (but then again maybe not, for he once said he hated scholars). Mrs. Molen fired my interest in literature, so I dedicate this page to her memory. Over the years I would sometimes encounter references to William Maxwell. As I began to work on this community history Web site in 2002 and had communication about it with Lincolnites, past and present, one of my high school classmates, Judge Bob Goebel, asked me if I had read any Maxwell. Bob's family in Lincoln had known some of Maxwell's relatives as neighbors, and Bob had written Maxwell in the early 1990s. My communication with Bob convinced me it was time to begin reading Maxwell to see what he had to say about our mutual hometown, especially its social classes. I have been interested in Lincoln's social history because of my experiences and observations of growing up there in the late1940s, '50s, and early '60s. Then, certain members of my family aspired to rise from the center of the middle class to the upper middle class. I was aware that firm boundaries existed from one social level to another and that there was a lot of social pretense in the community. For more information about my social enlightenment from growing up in Lincoln, Illinois, look under Additional Notes below for the link to "About Lincoln, Illinois, This Web Site, and Me." "Social Consciousness in William Maxwell's Writings Based on Lincoln, Illinois" appears in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (winter, 2005--06: pp. 254-286). This Journal kindly reprinted this article in its fall-winter issue of 2006--07 (99.3--4), pp. 228--262, in order to correct some printing errors. The Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society is devoted to formal scholarship and publishes only those articles that have been reviewed and recommended by professional historians. The Illinois State Historical Society (ISHS) is a non-profit organization whose 2,500 members include professional and amateur historians, educators, students, libraries, and museums. A link to the Web site of the ISHS appears toward the bottom of this page. (Note: A few years after I published this article, I wrote a complementary piece titled "Peeking Behind the Wizard's Screen: William Maxwell's Literary Art as Revealed by a Study of the Black Characters in Billie Dyer and Other Stories.") The Journal has generously granted permission for my article on Maxwell's social consciousness to be published as part of this community history Web site of Lincoln, Illinois. The current version of the article is a slightly expanded version of the original, including several more photos. The original article had 13,000 words and used 36 sources, including analysis of 16 works that William Maxwell based on Lincoln, Illinois. Biographical Sketch of William Maxwell (1908--2000). William Maxwell was born and raised in Lincoln, Illinois. His father was a successful traveling salesman for an insurance company (later, an insurance executive in Chicago), and the Maxwell family lived in the most exclusive neighborhoods in Lincoln. Maxwell biographer Dr. Barbara Burkhardt reports that Maxwell's mother died in the Spanish flu epidemic on January 3, 1918, two days after giving birth to her third son, Blinn. William Maxwell attended Central School (where Langston Hughes had graduated just a few years before) and Lincoln High School as a freshman. In 1924, after his freshman year at Lincoln High School, William joined his father; his older brother, Edward ("Hap"); and stepmother in Chicago, where the father had been transferred through a promotion in the Hanover Insurance Company. At the insistence of William Maxwell's Grandmother Maxwell, his younger brother, Blinn, remained in Lincoln to be cared for by her (to the later regret of William's father). Upon her death, Blinn was raised in Lincoln by a Maxwell aunt and her husband. (In adulthood, Blinn joined his brother Hap in a law partnership in California.) William Maxwell's father and stepmother retired to Lincoln, living on Park Place across the street from the house they had built in the early 1920s--the house described in So Long.

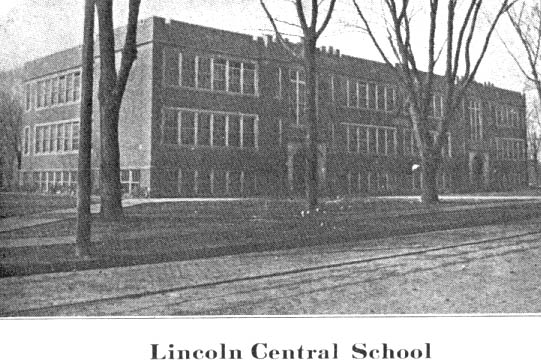

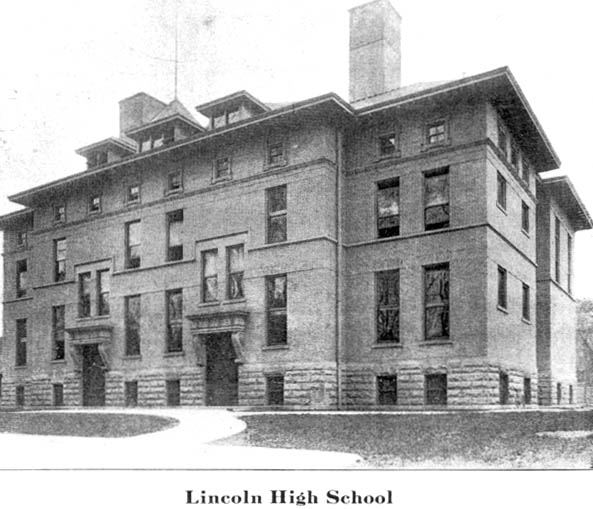

William Maxwell attended Central School

through the eighth grade, and he attended Lincoln High School his freshman

year before moving to Chicago, where he graduated from Senn High School,

located in the northern suburb of Edgewater . Source of photo:

Illustrated Lincoln, published Henry R. Fish, assisted by T.E. Perry

(William Maxwell's step-cousin), photos by A.B. Bliss, Lincoln, Illinois,

1916.

William Maxwell earned his undergraduate degree in English at the University of

Illinois at Urbana and gained his master's at Harvard. For forty years

(1936-1976) he was a well-respected fiction editor of The New Yorker

magazine, working with such major writers as Harold Brodkey, John Cheever,

Frank O'Connor, John O'Hara, Mavis Gallant, John Updike, and Eudora Welty.

The earliest of

Maxwell's Lincoln-based writing was accomplished during the time in

which he worked at The New Yorker. The owners were fond of Maxwell

and supported his writing by allowing flexible office hours and by giving

him occasional, timely leaves of absence. After his retirement as a fiction

editor, Maxwell was free to concentrate on his career as a writer, and he

continued to write about Lincoln, creating his major work, So Long, See

You Tomorrow, and such other important Lincoln-related stories as "Billie

Dyer" and "The Front and Back Parts of the House."

Beginning with his second novel, They Came Like Swallows (1937),

Maxwell used childhood memories from Lincoln as subject matter for much of

his work. This material included the pain of losing his mother and its effects

upon him as an adult as well as more pleasant memories of family and their

friends and neighbors. In The Chateau (1961), Maxwell wrote that in

his early adulthood he "began to cherish in my mind the people and scenes of

the past. It made a novelist of me." In one of Dr. Burkhardt's

interviews with Maxwell, he explained his motive for writing, and she quotes

him on this point in the Introduction of her acclaimed biography of him.

Maxwell said he desired "to recreate in a form that I hoped would have some

degree of permanence the character and lives of people I have known and

loved. Or people modeled on them. To succeed this would have to move the

reader as I have been moved. This is. . . the process that comes under the

heading of literary art" (7). Maxwell's most famous publication is the 1980

novel titled So Long, See You Tomorrow, which is about a

murder-suicide just east of Lincoln in January, 1921. |

|

The frieze of the Illinois State Library, opened in 1990 and facing the state Capitol, inscribes the names of thirty-five distinguished Illinois authors, including that of William Maxwell.

(Photo by Pat Hartman, 6-06)

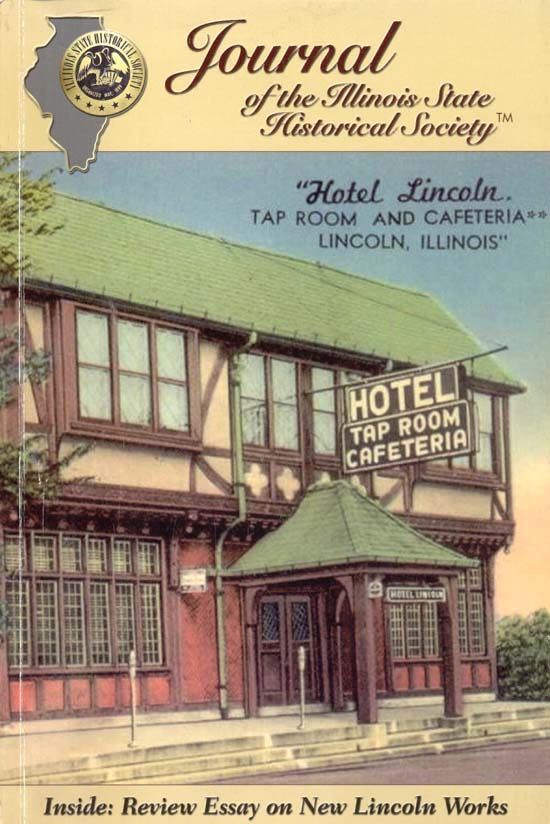

Cover of the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Winter, 2005-2006 Picture Postcard of the Hotel Lincoln (demolished) on Pulaski Street, Lincoln, Illinois, near Logan Street (Business Route 66). Postcard image courtesy of Fred Blanford. Source: C. L. Manning Advertising Services (Rockford, Ill., n.d.). The cover of the winter, 2005--06, issue of the Journal features a colorized picture-postcard image of the Hotel Lincoln. Its cafeteria is a setting in Maxwell's short story titled "The Value of Money." Now demolished, the Hotel Lincoln, a popular upscale destination for travelers of Route 66, was located on Pulaski Street near Logan Street (Business Route 66). This image of the Hotel Lincoln was provided by Lincolnite Attorney Fred Blanford, my good friend and collaborator on the community history Web site of Lincoln. The reverse side of this postcard, showing the interior of the Hotel's dining room, appears later in the article. |

|

Introduction. In his family history, Ancestors, William Maxwell characterizes late-nineteenth- and early- twentieth-century life in Lincoln, Illinois, the setting he uses for many of his short stories and novels: "Men and women alike appeared to accept with equanimity the circumstances (on the whole, commonplace and unchanging) of their lives in a way that no one seems able to do now anywhere. This is how I remember it. I am aware that Sherwood Anderson writing about a similar though smaller place saw it quite differently."1 While Maxwell found complacency and thus a lack of upward social mobility in Midwestern small-town life, Anderson saw restlessness and obsessive striving for material success. Yet Maxwell's portrayal of Midwestern small-town society--his social consciousness--is complex and enlightening: it is both broad and deep, sympathetic but realistic, as this article attempts to show. In this article, social consciousness means the portrayal of social classes in literature, including an author's stated or implied attitudes toward those classes and the characters who represent them. An emphasis on social history in creative writing, including fiction and memoir, is a facet of the gradual rise of realism and naturalism (determinism) in American literature in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Writers using Midwestern subject matter play prominent roles in these literary movements, and names of twentieth-century luminaries using Illinois subject matter come easily to mind, for example, Edgar Lee Masters, Vachel Lindsay, Carl Sandburg, James T. Farrell, and Saul Bellow. The background paragraphs below summarize how major late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century authors using Illinois subject matter have emphasized life on the prairie and in Chicago and have neglected small-town life. In contrast to this pattern, Author William Maxwell bases many works on his hometown of Lincoln, Illinois, a small town2 located about midway between Chicago and St. Louis on Interstate 55. This article attempts to explain Maxwell's distinctive use of realism and naturalism to portray social classes as he knew them in that community. A full analysis of middle-class culture in Maxwell's Lincoln-based literature, however, is beyond the scope of the present study. Background of Illinois Literature. Important writers of nineteenth-century Illinois commonly depict small-town life as incidental to their primary interest in the individual's experience in rural settings. Many writers of this period work in the romantic genres that were popular into the early twentieth century. Robert Bray identifies these fictional forms as the historical romance, romantic comedy, and "genre paintings," which he defines as "novels deliberately full of homely social history, sympathetically rendered folkways, and a localized setting that is usually rural and glorying in the fact."3 Other writers blend romantic (lyrical) and realistic elements, sometimes expressing ambivalence toward life on the prairie, for example, Eliza W. Farnham4 and Joseph Kirkland.5 A romantic, highly symbolic treatment of Illinois prairie life appears in the work of Francis Grierson.6 Many Midwestern writers of realism in the early twentieth century harshly criticize small-town life for its shallow culture, specifically its obsession with material success, its smugness, and its stifling conformity. Yet Robert Bray notes that "the country towns of downstate Illinois mostly escaped the critical attacks of the antivillage writers" because "the first-rate novelists ... were all busy dramatizing Chicago."7 (The towns of Fulton County, of course, did not escape from Edgar Lee Masters.) In an essay about Illinois literature titled "Fiction Since 1915," James Hurt explains that early in this period realism and modernism gave rise to naturalism.8 Modernist writers explore the inner life, using a plain style to describe "moments of illumination bound together less by narrative logic than by oblique associations and unique personal reactions."9 Naturalism employs realism to show how natural or social forces control and even destroy the individual. To demonstrate modernism and naturalism, Hurt discusses stories by Sherwood Anderson and James T. Farrell, and both stories are about life in Chicago. Hurt observes that Illinois fiction since 1960 shows diversity, which includes the continuing appeal and refinement of realism and modernism: "the ironic self-consciousness and the freedom of form."10

Introduction to

William Maxwell's Lincoln-Based Work. The work that Hurt discusses to demonstrate these qualities is William

Maxwell's So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980), which Hurt

characterizes as "one of the finest novels ever written about Illinois

life."11 Also, this novel won Maxwell the American Book

Award and the Howells Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. |

|

|

Set in the vicinity of Lincoln, Illinois, So Long intertwines two stories: in the central story, tenant farmer Clarence Smith murders neighbor Lloyd Wilson for his adultery with Smith's wife; then Clarence Smith commits suicide. In the other story, framing the first, the author-narrator tells of his boyhood friendship with Cletus, the murderer's son, a friendship the narrator feels he has betrayed. The author-narrator confesses to telling the tragic story as "a roundabout, futile way of making amends."12 The characters of So Long represent social and economic groups associated with the Illinois farm and small town, for example, tenant farmers, their hired hands, farm owners, and lawyers. Maxwell's characters typically reflect various socio-economic levels. William Maxwell drew upon his childhood memories of Lincoln, Illinois, and its nearby rural area for eleven short stories, four novels, and a book-length family history (These are identified in the footnotes.13) Maxwell's upper-middle-class family is at the heart of much of his Lincoln-based writing. Maxwell mainly depicts the domestic lives (and sometimes the inner lives) of the upper-middle-class family that he was born into, including relatives, their friends, and servants (black and white). In this respect, Maxwell's subject matter reflects the limitations of both childhood experience and writing about it from memory. |

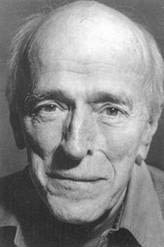

Photo of William Maxwell by James Hamilton in William Maxwell's Billie Dyer and Other Stories (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), dust jacket. In a memoir Alec Wilkinson observes that Maxwell's "eyes were dark and watery and expressive to the point of radiance, and they remained so all his life. ... When you looked into his eyes you felt you were looking into the eyes of someone who understood and accepted you. And didn't require from you something more than you could provide. Or that you be anyone but yourself. ... His attention was not restless. His acceptance made you feel valued." [Alec Wilkinson, My Mentor: A Young Man's Friendship with William Maxwell (New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002), 39-40]. |

|

In "Billie Dyer," Maxwell admits that as a child "I was not much better informed about the grown people around me than a dog or a cat would have been." As a child, Maxwell did not have a "big picture" of local society. Yet, Maxwell's writing presents a wide variety of well-developed characters, and Maxwell biographer Barbara Burkhardt notes that Maxwell's material extends "beyond the home and into the community." Background for Social Consciousness in William Maxwell. Professor Barbara Burkhardt notes the importance of the social-historical dimension of Maxwell's work: "The author can be regarded as an exemplary chronicler of American life prior to and between the World Wars. His carefully crafted details of everyday experience in both urban and smalltown [sic] settings carry on traditions of American Literary Realism ... ; he provides a distinct view of midwestern life and culture in the early decades of this century. ..."14 In her dissertation, Professor Burkhardt primarily deals with Maxwell's artistic development rather than his contribution to social history. In total, Maxwell wrote hundreds of pages of autobiographical fiction and memoir based on Lincoln, Illinois (Maxwell fictionalizes Lincoln as Draperville and Elmsville). Thus, Lincoln is one of the most extensively written about communities in downstate Illinois literary history, and this town in many ways is representative of countless small communities in Illinois and throughout the Midwest. Maxwell's literature based on Lincoln, Illinois, provides an unparalleled and valuable resource for the study of Illinois small-town social history, complementing the abundant literature about Chicago and adding to our understanding of Midwestern culture. |

|

|

A knowledge of Maxwell's source material helps us to understand his portrayal of society. The main source for Maxwell's writing about social class in Lincoln, Illinois, was his memory of the people he knew from childhood: family members, their white and black servants, neighbors, and family friends. A subject that often recurs in his writing is the death of his mother on January 3, 1919; she was a victim of the Spanish flu epidemic. At the end of his 1961 novel, The Chateau, Maxwell includes a one-paragraph memoir of how his mother's death affected his family and led to his writing career.15 In several works Maxwell connects memory of his mother with the Maxwell home on Ninth Street. Other sources that Maxwell sometimes used to supplement his memory were local history books; editions of the Lincoln Courier (under various names); and correspondence with such relatives living in Lincoln as his father, stepmother, and Step-cousin Tom Perry. Maxwell also traveled to Lincoln for his father's and stepmother's funerals (1958 and 1972, respectively) and at least once to visit his elderly Aunt Annette.16 Most likely, conversations with relatives and friends during those visits stimulated his memory and influenced his later writing. William Maxwell's boyhood home, Ninth Street, Lincoln, Illinois. This photo shows the house as it looked in 1903, just a few years before the Maxwell family lived there when it was occupied by the family of the original owner, James T. Hoblit. Source: Views of Streets, Residences, State Institutions, Public Buildings, Chautauqua Grounds, Portraits of Citizens, Lincoln, Illinois, 1903 (published by the Lincoln Woman's [sic] Club). Photo courtesy of Jay Burger. William Maxwell provides a three-page description of his boyhood home in Ancestors (pp. 185-188). The house had been owned by a prominent Judge Hoblit, who "went bankrupt." This house was "almost directly across the street from" the Blinns' house, where Maxwell's mother had grown up, so she was very familiar with this house before it became her home. She redecorated the house: "She couldn't bear dark varnished woodwork, and had it painted white upstairs and down. In the dining room the walls were dark green and the molding was black, requiring coat after coat after coat of white enamel. It was the only resistance the house put up. After that it was hers" (p. 186). Maxwell writes, "I didn't distinguish between the house and her, any more than I would have distinguished between her and her clothes or the sound of her voice or the way she did her hair" (p. 187).

Present-day

view of William Maxwell's

boyhood home and historical marker, Ninth Street, Lincoln, Illinois.

Photo courtesy of Leigh Henson. |

|

|

Overview of the Social Classes in Maxwell's Writing Based on Lincoln, Illinois. A close reading of Maxwell's writing (textual analysis) based on Lincoln to observe the attitudes, values, beliefs, and behaviors of the characters provides a foundation for grouping those characters into social classes. These classes form a composite of society. Maxwell's Lincoln-based work realistically reflects three groups of the middle class based on the wealth and social status, upper, the central, and the lower levels (a similar three-part classification had been devised and popularized by Professor W. Lloyd Warner, a noted twentieth-century American sociologist and anthropologist17). In the present article, the three middle-class groups are based on the occupation, income, and reputation of the author's characters. In Lincoln's society of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, these qualities of the male head of the household determined his family's social status. Like any system of classification, the lines from one category to another may blur. Characters in the upper middle class are those who have earned the most wealth, whether from superior professional expertise, investment, or inheritance. Maxwell implies that the most prestigious way to gain significant wealth was to acquire the rich farmland of Logan County, where Lincoln is the county seat. Typically members of the upper middle class are wealthy farmers and the most successful professionals, specifically lawyers, judges, doctors, and owners and managers of large, lucrative businesses. Some professionals combine roles, for example, law and ownership of or investment in business, industry, or real estate. For the few people who inherited enough wealth to live independently, Maxwell had only limited information. Maxwell's maternal grandfather, Edward Dunallen Blinn, was an attorney who managed a farm for a member of one of the largest land-owning families of Logan County: the Gilletts. William Maxwell was somewhat acquainted with John Dean Gillett Hill, a grandson of the Gillett family patriarch, John D. Gillett. Maxwell knew Hill as one of his father's best friends.18 Mr. Hill lived in an ornate, Spanish-style mansion on Lincoln Avenue, one of Lincoln's finest streets, close to Park Place, where Maxwell's father and stepmother had built their showcase, two-story stucco house in 1922. Maxwell's center of the middle class encompasses characters from a wide range of occupations. This category includes members of the lesser professions (lower-paying but respected), for example, the ministry and teaching; struggling business owners; and owners of small farms. The center of the middle class includes those who fell from the upper class and who had to spend very modestly. Also at the lower level of the center of the middle class are tenant farmers, store clerks, and secretaries. Although they do not earn as much as their employers and landlords, they are accorded a higher social status than members of the lower middle class. At the bottom of the middle class are the poor. They live at a subsistence level, working at menial jobs, whether steadily or sporadically. This group includes household servants (white and black), gardeners, garbage collectors, and hired farm hands. Even responsible servants, of course, have a modicum of respectability. None of Maxwell's characters represent the underclass of gypsies and hobos who traveled through a town that was served by key state highways (Route 4, which later became U.S. Route 66; Route 10; and Route 121) and three major railroads: the Gulf Mobile and Ohio, the Illinois Traction System (interurban), and the Illinois Central. The following observation by Maxwell on community mores probably applied mostly to the upper and central middle class, but perhaps also to the lower middle class, to some extent: "You could be eccentric and still not be socially ostracized. You could even be dishonest. But you could not be openly immoral. The mistakes people made were not forgotten, but if you were in trouble somebody very soon found out about it and was there answering the telephone and feeding the children."19 Maxwell's Portrayal of the Upper Middle Class. The social structure of Lincoln, Illinois, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was rooted in the original and primary source of wealth in central Illinois: the amazingly productive farmland, which yielded such abundant cash crops as corn and wheat, and grasses to support livestock. Maxwell summarizes the relationship between the farmland and social stratification, showing that farmland ownership gave people a sense of social superiority: The black fertile soil of Logan County was, and so far as I know still is, owned by people whose ancestors came from Kentucky or Indiana or Ohio, bringing with them no more than they could fit into a lurching covered wagon. They staked out as much land as they had a fancy to and cleared it slowly, putting a few more acres under cultivation each year. Their children and grandchildren, born on this land, felt they belonged there. Their great-grandchildren either sold their patrimony or got someone else to farm it for them. Living in town quite comfortably in big old houses set well back from the street, they kept an eye on what was going on out in the country, and when the crops were delivered at the grain elevator they took, as was customary, half the profits. They did not consider a tenant farmer their social equal, any more than a carpenter or a stonemason or a bricklayer. The farmer who owned the land he farmed they could and did accept.20 Members of the professions and business people, such as Maxwell's father, aspired to be landowners for wealth and social status: "Lincoln itself was a farming community, and owed its prosperity to the rich farmland that lay all around it. It was also a place that successful farmers retired to when they were ready to give up farming and spend their declining years at the Elks Club, playing rummy. And there were a certain number of men in Lincoln who, like my father, owned land which they kept a careful eye on and from which they derived a substantial part of or even all of their income."21 Maxwell's father eventually owned at least two farms: one was a 360-acre farm east of Lincoln with a Mt. Pulaski address. An example of a character who owned farmland in the early 1920s and who had the respect of people she had business with is Mrs. Stroud, Lloyd Wilson's landlady in So Long, See You Tomorrow. When Mrs. Stroud's husband died, "the president of the bank began to explain things to her. He started in as though speaking to a child and then had to pull himself up short. It had been his fixed opinion that all women are ignorant about money matters, but this woman didn't happen to be, and the questions she put to him were just the questions he would have preferred not to answer. It was quite impossible to take advantage of her."22 Mrs. Stroud also liked to visit her farm unannounced and reprimand Lloyd Wilson for something he neglected (he often took time to help neighbors). Wilson does not argue with her. Mrs. Stroud is secretly attracted to Lloyd Wilson, but she does not give in to sexual impulse because of "the cruelty of Lincoln gossip."23 Lloyd Wilson does fall victim to illicit passion for his neighbor's wife, Fern Smith. In a touch of social Darwinism, Maxwell suggests that a member of the upper middle class, Mrs. Stroud, is smarter than her socially inferior tenant farmer, Lloyd Wilson. Lincoln became the commercial center because farmers traveled to Lincoln for goods and services. Successful shopkeepers and professional workers belonged to the upper middle class. Many shop owners were of German descent, including Jews. In "With Reference to an Incident at a Bridge," Maxwell provides a rare description of German Jewish families in Lincoln: "There were a dozen or more old families in town who were German Jewish. The most conspicuous were the Landauers and Jacobses. Nate Landauer ran a ladies' ready-to-wear shop on the north side of the courthouse square, and his brother-in-law, Julius Jacobs, a men's clothing store on the west side of the square. Once a year my father or my mother took my brother and me downtown and we were fitted out by Mr. Jacobs with a new dark-blue suit to wear to church on Easter Sunday."24

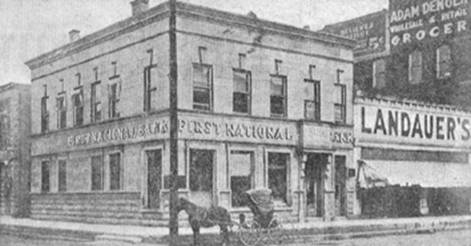

Early-twentieth-century photo of the First National Bank (the building is an enduring landmark), Landauer's, and Denger's on the Broadway Street side of the Logan County Courthouse square. Source: Lincoln Evening Courier, centennial edition, August 26, 1953, sec. 3, p. 4, col. 5.

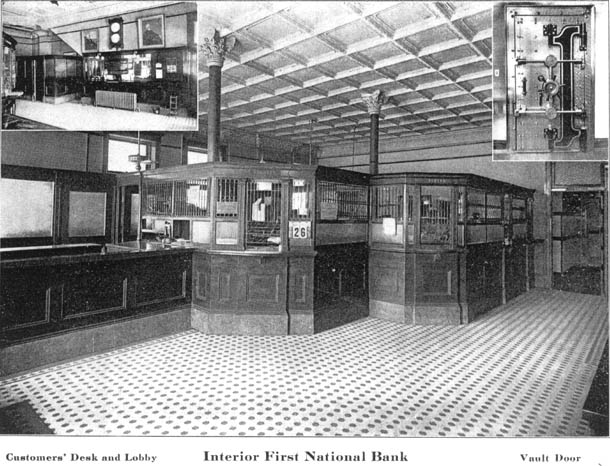

The First National Bank described itself as the oldest bank in Logan County. The above photo shows the bank's austere, fortress-like interior as it would have been seen by the people depicted in William Maxwell's writings based on Lincoln, Illinois. Source: Illustrated Lincoln, published Henry R. Fish, assisted by T.E. Perry (William Maxwell's step-cousin), photos by A.B. Bliss, Lincoln, Illinois, 1916. Reflecting on the Jewish shopkeepers in Lincoln, Maxwell suggests that the townspeople of various ages were accepting and unprejudiced: The school yard had various forms of unpleasantness, but anti-Semitism was not one of them. In the Presbyterian church, the doctrine of Original Sin was held over our heads, with no easy or certain way to get off the hook. It was hardly to be expected that the Crucifixion was something the Jews could live down. But on the other hand, it was a very long time ago, and the Landauers and the Jacobses were not present. Mrs. Landauer and Mrs. Jacobs both belonged to my mother's bridge club. At that age, if I thought about social acceptance at all it was as one of the facts of nature. Looking back, I can see that manners entered into it, but so did money. The people my parents considered to be of good families all had, or had had, land, income from property, something beside wages from a job.25 Willliam Maxwell's parents and both sets of grandparents belonged to the upper middle class. Both of William Maxwell's grandfathers were attorneys in Lincoln. William's knowledge of his maternal Grandfather Edward Dunallen Blinn gave him passing familiarity with prominent figures in local and state history. Blinn was a close friend of three-term Governor Richard J. Oglesby, in turn a friend of Peoria Attorney Robert G. Ingersoll. Blinn and Oglesby were fascinated with religion, and William Maxwell's father inherited Blinn's twelve-volume collection of Ingersoll's works, including Why I Am an Agnostic.26 Writing from childhood memory, Maxwell lacked personal experience with those who lived at the highest and lowest social levels, but Maxwell family history included some information about a few people who inherited enough wealth to live independently. Both of William Maxwell's grandfathers knew the Gilletts, who were among the largest landowners in Logan County.27 Maxwell's father's friend, John Dean Gillett Hill, probably owned enough farmland to be independently wealthy, and his work as a lawyer may have been just a paying hobby. Nothing in Maxwell's writing refers to the Scullys, who owned even more land in Logan County than the Gilletts and who were some of the largest landowners in the Midwest. William Maxwell's grandfathers were attorneys who represented opposite sides in a case involving a family dispute over John D. Gillett's estate. Edward Dunallen Blinn represented Mrs. Emma Gillett Keyes Oglesby, the eldest Gillett daughter, who had married Richard J. Oglesby; and William Creighton Maxwell represented another daughter, Miss Jessie Gillett: "My Grandfather Blinn won the case, who didn't need to win it. ... My father used to say that it was the first case my Grandfather Maxwell ever had where the fee was substantial, that the part he took in the trial considerably enhanced his reputation, and that if he had continued to be Miss Jessie Gillett's legal advisor he would no longer have worried about the bill from Boyd's Dry Goods Store [where Mrs. Maxwell overspent]. Instead, his health broke down. Other lawyers attended to Miss Gillett's legal affairs. ..."28 According to their social status and the times, William Maxwell's grandmothers worked at home, supervising the children and servants. Mrs. Maxwell (d. 1914) was the only grandparent who lived long enough for William to remember very well. As a child, he visited her weekly and often spent the night. He offers a loving but realistic sketch of her in Ancestors based on memory and information from his father. Maxwell's father had told him about the arguments over money in the Robert Creighton Maxwell home caused by Mrs. Maxwell's credit purchases at A.C. Boyd's. Mrs. Maxwell was apparently more concerned with religion than money. Her ancestors had founded the Church of Christ, and she was a devout proponent of this Protestant denomination: "My Grandmother Maxwell believed that there was only the Christian Church; every other religion was a mistake. ..."29 "She never stopped talking about immersion, or thinking about it. She kept track of who was and wasn't. She had the makings of an evangelist."30 (More information about Maxwell's grandparents, including photos of Blinn and Maxwell family gravestones in Old Union Cemetery, appears in the book-length community Web site history titled Mr. Lincoln, Route 66, and Other Highlights of Lincoln, Illinois.31)

Artistic rendering of Boyd & Paisley Dry Goods Store in the Gillett-Oglesby Building on Kickapoo Street on the Logan County Courthouse Square. Source: the "Preservation Begins at Home" poster sponsored by City of Lincoln, Main Street Lincoln & the Courier - dated May 11-17, 1997. Other key figures in Maxwell's treatment of the upper middle class are literal portrayals of his parents or fictional characters based on them. Maxwell's father was born into an upper-middle-class family, and as previously noted, he succeeded in the insurance business in Lincoln and Chicago, owning comfortable homes and farmland.32 Maxwell's mother, Eva Blossom, the second of three daughters of the Edward Dunallen Blinns, was also born into the upper middle class, and she helped her husband maintain their status in it. Her death in 1919 from the Spanish flu profoundly affected her ten-year-old son, William. As Professor Burkhardt notes, "The death of Maxwell's mother clearly established the writer's yearning to safeguard the past; his claim that the tragedy made him a novelist does not seem exaggerated. In fact, his convictions about the beloved, unregainable past fuel the philosophy behind his work.33 Maxwell describes his mother in several works, and his most extensive fictional portrayal of her is Mrs. Morison in They Came Like Swallows (1937). The opening chapter of this novel, Maxwell's second, paints an intimate portrait of himself as the eight-year-old Bunny and Bunny's patient, indulgent mother. The other two chapters focus on Bunny's older brother, Robert; the father, James; and the impact on the family of Mrs. Morison's death.

Maxwell uses his father as the basis of several upper-middle-class male figures, ranging from the unsympathetic father, Mr. Peters (in The Folded Leaf), to several highly sympathetic figures in other works. Money is a central issue in the father-son relationships. Mr. Peters lectures his son with work-ethic platitudes, including the first principle of learning "the value of money." Mr. Peters' son, Lymie, an undergraduate at the University of Illinois, is not interested in money but in literature, art, and a privileged lifestyle that included socializing with interesting, friendly professors. In other works, Maxwell's father figures are unselfish. In the autobiographical short story, "The Value of Money," Edward Ferrers, a forty-three-year-old associate professor, travels to his hometown of Draperville to visit his father (a successful, retired businessman) and stepmother. Upon arriving, Edward asks about going to the bank so he can cash a check for ten dollars. When his father hands him two ten-dollar bills, Edward says he will give his father a check when they get to the house. Edward knows his father takes money very seriously: "As a sullen adolescent Edward had accused his father–often in his mind and once to his face–of caring about nothing but money."36 In the final scene of the story, Mr. Ferrers explains that he does not judge people strictly on how much money they make, as does his other son, Edward's older brother. Mr. Ferrers respects Edward for caring about "other things" and being "content to have a little less money and do the kind of work that interests you."37 Then, Mr. Ferrers tears up his son's check for the twenty dollars. In Ancestors, Maxwell writes that he sometimes went with his father to visit the poor black servant, Mrs. Dyer, who had faithfully worked for Mr. Maxwell when his wife had died and he desperately needed household help. Maxwell reports that during those visits his father always gave her a new ten-dollar bill.38 "The Value of Money" features a scene in the cafeteria of the New Draperville Hotel that expresses a positive view of upper-middle-class society in Lincoln. In this scene Edward is having dinner with his father, stepmother, and family friends. Most likely, this hotel was based on the Hotel Lincoln, an attractive Tudor-style structure, pictured below. The Hotel Lincoln was a popular destination for affluent travelers in early to mid twentieth century. Maxwell's cafeteria scene is significant because it captures the pride that characterized the upper-middle-class inhabitants of a small, typical Illinois town.

Dining Room of the Hotel Lincoln Maxwell describes the upper-middle-class diners: "The faces he [Edward Ferrers] saw were full of character, as small-town faces tend to be, he thought, and lined with humor, and time had dealt gently with them. By virtue of having been born in this totally unremarkable place and of having lived out their lives here, they had something people elsewhere did not have. ... This opinion every person in the room agreed with, he knew, and no doubt it had been put into his mind when he was a child. For it was something that he never failed to be struck by–those sweeping statements in praise of Draperville that were almost an article of religious faith."39

Unidentified 1950s Diners at the Hotel Lincoln. Photo courtesy of Fred Blanford. The dominant upper and central middle classes defined Lincoln's culture, and its mores were somewhat complex and paradoxical. People could be both smug and sociable, materialistic and charitable. Maxwell's attitude toward the dominant culture is largely sympathetic, but not always: usually his descriptions approvingly show the proud contentment of the upper middle class to which Maxwell's family belonged, but Maxwell is capable of social criticism, as explained later. The preceding description of the diners in the Hotel Lincoln suggests that upper-middle-class Lincolnites were smug, but Maxwell shows that at least some members of the upper middle class believed their financial success carried social responsibility. Maxwell, for example, in referring to the previous generation, describes his Grandfather Blinn as a "public-spirited man." Blinn had earned large fees and had invested a lot of money in the town's street car and telephone-telegraph companies as "local improvements." Both of these companies were "shaky enterprises" and required continual investment. Blinn also lent money freely to people based only on their family names: "Young men who went to him for financial help usually got it, and his indifference to money seems to have extended to large sums as well as small ones. In the midst of a busy life, he often didn't bother to put in writing the loans he made." His law partner questioned why he lent money to people who most likely would not repay it, and Blinn replied that he knew their fathers. His children inherited substantial sums, but not as much as they might have.40 In Time Will Darken It (1948), Maxwell makes dramatic use of a sense of social responsibility about money. In this novel, set in 1912, a main character from the upper middle class, Attorney Austin King, faces a difficult moral dilemma. Austin's foster cousin, Rueben Potter, visiting from Mississippi, had solicited some of Austin's friends to invest in a vague business deal. Austin does not invest, but agrees to draw up the papers. The business venture proves to be a bust, and Austin's "friends" want to hold him responsible, so his dilemma is whether to repay them. Austin also feels a vague moral indebtedness to Potter, whose father raised Austin's father. Yet Austin puzzles over the time his own father refused to help Potter financially. Feeling confused and somewhat blameworthy for having introduced his friends to Potter, Austin seeks advice from a venerable neighbor, Dr. Danforth, a successful and popular horse veterinarian. Dr. Danforth assures Austin that "you can go on paying them [investors] back forever, and still be indebted to them."41 Danforth also emphasizes that Austin's friends "went into it [the bad deal] with their eyes wide open" and that Austin has no moral obligation. Time Will Darken It is Maxwell's most intricate work to present characters from the upper middle class. This novel deserves more critical praise than it has received because of its detailed portrayal of manners and morals in pre-World War I Midwestern society. The novel's two main female characters foreshadow feminist concerns that would emerge later in the century. Both Austin's wife, Martha, and his young, attractive cousin, Nora Potter, visiting with her family from Mississippi, are unhappy and struggle to imagine the kind of life that would satisfy them. Martha is troubled by the rumors of an illicit relationship between her husband and Nora, and Martha questions Austin but does not accuse him of being unfaithful. Yet the stress of the rumors adds to Martha's frustration and dissatisfaction. Apparently she never did love her husband, and she comes to see her marriage of convenience as intolerable. At the end of the novel, on her first night home from giving birth to her second child, a son, Martha King lies in bed next to her husband and contemplates leaving him as he lies asleep with his arm around her: "She moved slowly and carefully, out from under the cover, being careful even in her anger not to waken him. ... Not that she was afraid of him any longer, but she had to be alone, to think, to decide what she would do when she got her strength back. Because she wouldn't stay in the house with him a day longer than she had to. ..."42 Maxwell endows this white middle-class wife with feelings that would have been uncommonly bold in 1912. Nora Potter is also a complex figure whose desire for independence was unconventional for the time. Nora's aunt discovers her reading Robert Ingersoll, the agnostic, in the Kings' living room and tells her to stop, but she has a mind of her own. Nora confides in Bud Ellis, "I have a great deal to say, but it isn't recipes, and that's all the women at home ever talk about. ... If you say something that's an idea, they look at you as if you'd just gone out of your mind."43 She rejects the advances of Bud Ellis, a married man, but is passionately attracted to Martha's husband, Austin, who does not reciprocate although he sympathizes with her desire to escape the limitations imposed on the roles of women by early twentieth-century society. Yet Nora is quixotic in her vision of her future as "the foremost woman lawyer in the State of Illinois." When Nora tells Austin that she would like to become a lawyer and asks him to help her by allowing her to read law in his office, he reluctantly agrees. (In contrast, Austin's law partner is the senior member of the firm, and he disapproves of this idea as bad for their business.) To pursue her desire for independence, Nora remains with the Kings' neighbors, the Beaches, when her parents returned to Mississippi. Nora works with the Beach sisters when they open a kindergarten in downtown Draperville. One December morning when Nora tries to start a fire in the stove of the classroom, she pours kerosene on the smoldering flames and is badly burned, her face disfigured. Nora had wanted to escape what she considers a pathetic, mindless adulthood, but her naive striving has led her into an unfamiliar social milieu and thus into a tragic circumstance. Building a fire in a stove proves dangerous for Nora because she lacks experience with it. Most likely, if she had not left Mississippi, her social status there would never have required her to perform the work of a servant. At the end of the novel, Nora's future looks bleak, and she is greatly depressed. Time Will Darken It thus reflects a theme in the works of Henry James: that when a person leaves a familiar social-cultural milieu for an unfamiliar one, tragedy can result. In addition to grandparents and parents, Maxwell's work offers portraits of many other family members, including aunts, uncles, his older brother Edward ("Hap"),44 and family servants. These figures mainly appear in Ancestors and the short stories. In childhood Hap had lost a leg in a carriage accident, but he possessed an indomitable spirit that made him competitive in athletics and high school debate and later enabled him to become a successful lawyer. A few other of Maxwell's memorable characters from the upper middle class are outside his family. In the realistic tradition, Maxwell presents some of these as sympathetic figures, some not. The most complete portraits are those of the Donalds,45 neighbors of the Maxwells on Ninth Street; two of William Maxwell's father's friends;46 and Mrs. Sinclair in "What Every Boy Should Know." In this story of growing up in a small town, the main character is the autobiographical eleven-year-old named Edward Gellert; he is a paperboy for the Evening Star, owned by Mrs. Sinclair. When the paperboys strike for more money and better hours, she holds out until the boys back down. Then she calls them in one at a time to lecture them on the need for loyalty, teaching them a harsh lesson about the power of ownership/management over labor. When someone runs over Edward's bicycle in front of the newspaper building, Mrs. Sinclair shows no sympathy when she walks out to the sidewalk and tells Edward, with tears streaming down his face, "You're not supposed to leave your wheels in front of the building."47

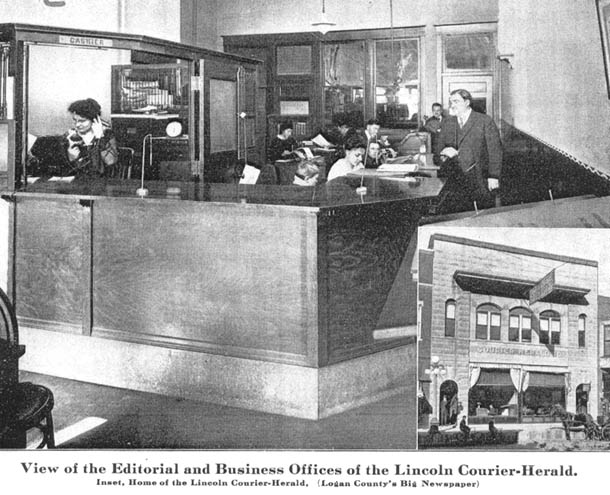

The Lincoln Courier-Herald, located on Kickapoo Street one block north of the courthouse square, looking much as it did in 1921, when William Maxwell was one of its delivery boys. The inset shows the exterior with paperboys on their bicycles next to the high curb. Source: Illustrated Lincoln, published Henry R. Fish, assisted by T.E. Perry (William Maxwell's step-cousin), photos by A.B. Bliss, Lincoln, Illinois, 1916. Maxwell typically approaches his characters with sympathetic restraint, but Time Will Darken It includes a rare, amusing passage of social satire on the upper middle class. In "1" of Part Five: The Province of Jurisprudence, affluent female gossips are the target of Maxwell's wit. They conduct "research" on other people's private lives. When the "Friendship Club" meets for lunch and bridge, "they slipped all pity off under the table with their too-tight shoes, and became destroyers, enemies of society and of their neighbours, bent on finding out what went on behind the blinds that were drawn to the window-sill."48 Other characters outside the family of particular significance to William Maxwell's depiction of Lincoln society are the servants who had worked in his parents' home. The next three paragraphs discuss upper-middle-class members' relationships to their servants, who are further considered in the later section on the lower middle class. Maxwell writes that his parents regarded blacks with more consideration than some other white Lincolnites did: "One of the things I didn't understand when I was a child was the fact that grown people–not my father and mother but people who came to our house or that they stopped to talk to on the street– seemed to think they were excused from taking the feelings of colored people into consideration. When they said something derogatory about Negroes, they didn't bother to lower their voices even though fully aware that there was a colored person within hearing distance."49 In Time Will Darken It, Attorney Austin King (living in Draperville-Lincoln) reflects the way Maxwell's parents regarded blacks, in contrast to the way the Kings' Southern guests, the Potters, do. This difference is apparent in a scene in which Thelma, the daughter of the black housekeeper-cook, puts away silver and china in the dining room while the Kings and Potters are visiting in the next room. Austin is concerned that the language of the visiting Potters will be offensive: "The word 'nigger,' which was so often on the lips of the Southerners, she [Thelma] did not appear to notice, and the Potters were unaware of any lack of tact on their part, even when Austin King got up quietly and closed the dining-room doors."50 In this novel the Kings are not the only upper-middle-class whites who behaved kindly toward their black servants. Again, Thelma is the focal character when she causes a minor problem for one of the daughters of the Kings' good neighbors, the Danforths. Lucy Danforth, her sister, Alice, and Nora Potter had begun a private kindergarten in the upstairs of a building in the business district, and they hire Thelma's brother, Eugene, to start a fire in the stove early before the others arrive. While the kindergarten is closed, Thelma convinces her brother to allow her to gain entry to the kindergarten without permission. Early one morning Lucy discovers Thelma making a "fresco" with crayons and paper. Lucy says she will have to tell Thelma's mother, and Thelma's hands shake at the prospect of a beating. Lucy then has second thoughts: "So contagious is remorse that Lucy said, 'You can take this with you if you like,' and presented Thelma with her own half-finished drawing of a woman in a garden, with shears and a basket full of flowers – poppies or anemones or possibly some flower that existed only in Thelma's mind."51 Maxwell's Portrayal of the Center of the Middle Class. Maxwell's center of the middle class is broad: it includes such professionals as ministers and teachers, business people of limited success, and industrious tenant farmers. People in these groups successfully managed their expenses but never gained enough material wealth to rise to the upper middle class. Some in this category had fallen from the upper middle class, as indicated below in the case of Maxwell's Uncle Ted Blinn. According to Maxwell, the Russian Jews of Lincoln were more recent immigrants than the German Jews and failed to rise to the upper middle class: "When I try to recall what the inside of Mr. Rabinowitz's store was like, what emerges through the mists of time is an impression of thick-soled shoes, heavy denim, corduroy, and flannel–work clothes of the cheapest kind. The bank held a mortgage on the stock or I don't know Arkansas. The chances are that he held out until the Depression and then went under, along with a great many other people whose financial underpinnings were more substantial."52 In his treatment of his Uncle Edward Dunallen Blinn, Jr., (Ted), Maxwell describes an example of someone who fell from the upper middle class. As indicated earlier, Uncle Ted's father, Edward Blinn, Sr., was a self-made man: a very successful lawyer, judge, and respected citizen. Maxwell summarizes the difference between Uncle Ted and his parents: "What the older generation admired and aspired to was dignity, resting on a firm basis of accomplishment. I think what my uncle had in mind for himself was the life of a classy gent, a spender–someone who gives off the glitter of privilege. And he behaved as if this kind of life was within his reach. Which it wasn't."53 Ted had lost an arm in a car accident and had suffered a failed first marriage. He never developed a career in a profession, and after his parents' death he sometimes resorted to forging checks for small amounts. After working many years as a ticket agent for the Illinois Traction System (interurban) in Champaign, Illinois, he ended up running the elevator in the Logan County Courthouse, where townspeople remembered his father had practiced law. Then, his second wife, Edna, worked at the Lincoln Public Library, her small salary the key to their subsistence. Maxwell reports that she loved Ted and took care of him as they lived in genteel poverty. In Ted's later life, Maxwell and he became friends.54 Maxwell's most significant publication with main characters from the center of the middle class is So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980), and this novel's main characters are tenant farmers (the author-narrator, a member of the upper middle class, may also be considered a main character55). A preceding section quoted Maxwell's observation that owners of small farms were somewhat accepted by the owners of large farms, but Maxwell also reports that townspeople tended to stereotype those who worked the land and felt superior to them: "On Saturday nights the farmers drove into town in their buckboard wagons, and I saw them roaming the courthouse square with unsmiling faces when we drove downtown for an ice cream soda. At that period, rising in the world meant giving up working with your hands in favor of work in a store or an office. The people who lived in town had made it, and turned their backs socially on those who had not but were still growing corn and wheat out there in the country. What seemed like an impassable gulf was only the prejudice of a single generation, which refused to remember its own not very remote past."56 In So Long, See You Tomorrow the main characters are cuckold-murderer Clarence Smith and his victim, adulterer Lloyd Wilson. They rented neighboring farms near Lincoln and had been good friends who helped one another when problems arose. Maxwell based this tragedy on a true story, relying on memory and newspaper accounts. Maxwell also needed additional information about farm life. As a child, Maxwell remembered carriage rides with his family and their friends when they drove in the country so the men could observe the crops and livestock. The author had also spent time on farms in Wisconsin in his early adulthood, but those experiences did not provide sufficient enough information for So Long. Maxwell thus spent a year of research and reflection before he felt comfortable writing about the kind of farm life his childhood friend, Cletus, son of the murderer, would have known.57

So Long accurately pictures

the grueling life on the farm and the severe consequences of a legal

system experienced by men and women involved in marital disputes.

Maxwell does not attempt to add layer upon layer of oppressive realistic

details as seen in the works of such naturalistic novelists as Frank

Norris and Theodore Dreiser. Instead, he offers a few suggestive

details: the tenant farmers' "hands were large and looked swollen or

misshapen and sometimes they were short a finger or two,"58

and the farm wives are typically like Mrs. Wilson, who "worked like a

slave, from morning till night."59 The court orders Lloyd

Wilson, the adulterer, to pay his wife "$9,000, which in 1921 was a lot

of money," and he is bankrupted, but denied a divorce and the freedom he

desires.60 The court rules against Clarence Smith, whose wife

had committed adultery, and he must pay her alimony and yield custody of

their children.61 Bitter and depressed, Clarence Smith kills

Lloyd Wilson, then commits suicide. Maxwell uses a plain, direct style

that belies the complexity of his novel's design in which the story of

the author's lost friendship with Cletus frames the domestic tragedy.

The unadorned style sharpens the novel's tragedy: individuals suffer

from flawed morality and from living in harsh, impersonal natural and

social environments. |

|||

|

Paul Beaver, Sr. |

Paul Beaver, Sr., shown here in 1925, owned a farm in Corwin Township of Logan County and was a contemporary of the men used as the basis for Maxwell's tenant farmers. Paul Beaver, Jr., history professor emeritus at Lincoln College, is an authority on Abraham Lincoln and the Scullys, owners of the largest number of tenant farms in Logan County from the 1850s to the present. [See Paul J. Beaver, William Scully and the Scully Estates of Logan County, Illinois (n.p., 2003).] |

||

|

Photo

source: Paul E. Gleason and Paul J. Beaver,

Logan County Pictorial History (St.

Louis, Mo.: G. Bradley Publishing, 2000), 21.

Deer Creek Gravel Pit one mile east of Lincoln on Illinois State

Route 121, where the real-life counterpart of Clarence Smith committed

suicide. Photo courtesy of Leigh Henson. Another character of the center of the middle class who degenerates is Miss

Ewing in Time Will Darken It. The fifty-one-year-old,

eccentric Miss Ewing is the only

secretary of the law firm of one of the main characters, Austin King.

Her

work has given her as much knowledge of the law "as the average attorney

ever needs to know." Her flaw is that she is "self important" and

obsessed with managing the office. When Nora Potter begins

to read law in this office, Miss Ewing's control is threatened. Miss Ewing

also may be jealous of Nora Potter, who has a better chance of entering the

legal profession than Miss Ewing had when she was young. Miss Ewing is

totally frustrated: "the only thing Miss Ewing didn't know was how to drive

Nora Potter out of the office, how to send her weeping down the stairs." As

a result of this frustration, Miss Ewing

suffers a kind of emotional breakdown. She confesses to Austin King that she

has been forging her employers' names on checks and manipulating the firm's

books to conceal the crime, but an audit reveals nothing wrong. Apparently

her delusion provides her the excuse she needs to remove herself from the

law office because with Nora Potter there, Miss Ewing can no longer entirely

control its day-to-day operations. Austin King offers to pay for Miss Ewing

to go to a nursing home in Peoria so she can recuperate, but she is not

interested. Miss Ewing shows further delusion by telling Martha King that

her husband is having an affair with Nora Potter. Miss Ewing's loss of her

job and her delusions will most likely cause her to be destitute and institutionalized. |

|||

|

Maxwell's Portrayal of the Lower Middle Class. The following discussion considers how Maxwell sometimes uses minor characters from the lower middle class to show traits of main characters, who are from the upper middle class, and to advance the plot. Also discussed below are two of Maxwell's later works in which the main characters are from the lower middle class. On tree-shaded Ninth Street, William Maxwell's parents lived in a traditional neighborhood with fine old houses, but they lived near a lower-middle-class neighborhood. Thus, as a child, Maxwell was in close proximity to observe life in that part of town, and he remembered that his parents had employed servants who lived in the poor neighborhood nearby. One half block west of the Maxwells' home was the intersection of Ninth and Elm Streets, and west of Elm Street "the neighborhood took on an altogether different character. The houses after the intersection were not shacks, but they were not a great deal more. Grass did not grow in their yards, only weeds."62 This lower-middle-class neighborhood was integrated: "In this down-at-the-heel neighborhood a few white families and most of the Negroes of Draperville [Lincoln] lived on terms of social intimacy to which there were limits. ..."63

Ms. Callie Gorens and unidentified black male with houses "not much more than shacks" in the Ninth Street neighborhood. Photo courtesy of Leigh Henson. In the world east of Elm Street, the upper-middle-class whites considered themselves superior to their servants and were thus distanced from them. The servants knew more about their employers than the employers knew about their servants: "Something like a great pane of glass, opaque from one side, transparent from the other, divided the two halves. ... Beulah Osborn, the Ellises' hired girl, Snowball McHenry, who worked in Dr. Danforth's livery stable, and the Reverend Mr. Porterfield, who looked after Mrs. Beach's furnace from October until April and her flower garden from April until October, knew a great deal about what went on in the comfortable houses on the hill. But when they or any of their friends and neighbours passed under the arc light at the intersection, the comfortable part of Elm Street lost all contact with them."64 The barrier between employers and their servants prevents Martha King from understanding the reason for her black housekeeper's request to have her daughter with her during the day. Rachel, the servant, wants to keep Thelma with her at the Kings' house during the day to protect her from Rachel's abusive husband: "It was the way his eyes followed Thelma."65 Martha, of course, grants the favor without knowing the reason or even asking about it: "This request ought to have made the whole thing as clear as daylight, and perhaps would have, if it hadn't been for the great pane of glass, which kept one part . . . from knowing what the other part was up to."66 In two of his major works, Maxwell uses characters from the lower middle class as foils (counterpoint figures) for main characters. In these instances, the main characters are upper-middle-class men suffering the kind of suicidal despair seen in George Bailey of It's a Wonderful Life. These male figures, wandering about literally and figuratively in the dark night, unexpectedly encounter derelict-like figures whose presence is severely disturbing. In They Came Like Swallows, James Morison [literary counterpart of William Maxwell's father] has just lost his beloved wife, Elizabeth. The night before his wife's funeral, Morison is despondent, and he wanders the neighborhood, preoccupied with grief as he enters an alley. He imagines Elizabeth has "come after him in the pony cart ... to take him home. ... He began to run along the alley, stumbling and falling and picking himself up again. He ran until he was stopped by the lean shape of a horse, and a wagon with a lantern on it. The lantern shone upward into a man's face that was thin and patient and crazy."67 The man is Crazy Jake, and his ghastly image helps to shock Morison out of his self pity. The next day, just before the funeral, Morison realizes "it would be years probably before he could make Robert [literary counterpart of the oldest son, Edward] understand what happened when he met Crazy Jake collecting tin cans at midnight."68 Undated photo of late-19th-- early-20th-century garbage collector in Lincoln, Illinois. Source: Lincoln Evening Courier, centennial edition, August 26, 1953, sec. 5, p. 11, col. 1. In Time Will Darken It, Austin King has become depressed after he fails to help restore his attractive, young Cousin Nora's desire to live. She had fallen in love with him without any hope he could love her. Then, she accidentally burned herself when she used kerosene to try to kindle a stove fire. Hospitalized, with her face and hands disfigured, she said she did not want to live. Feeling somehow guilty, Austin visits her in the hospital with good intentions, but he only upsets her so much she becomes hysterical, and he leaves, humiliated and despondent. From the hospital Austin wanders the streets and alleys of the courthouse square and business district. Meanwhile, in a twist of dramatic irony, his expectant wife, Martha, begins a complicated labor. Across the street from the county jail, Austin suddenly encounters a frightful figure named Hugh Finders, "who had been connected with a brutal murder some twenty years before."69 Finders is now "an old man with a cancerous skin condition and wisps of dry white hair sticking out from under a filthy cap."70 Finders tells Austin, "I was always interested in you on account of your father. He was a fine man. Nobody ever went to him in trouble that didn't get help. First, he'd give them a lecture, and then he'd reach down in his pocket. He used to think I drank too much and I guess maybe he was right, but we can't all sit up there, high and mighty, and pass judgment on our fellow men."71 These comments further depress Austin because compared to his father, he considers himself a failure. As a result, Austin finds himself at the depot, thinking about throwing himself in front of a train. Finally, Austin comes to his senses: "And I felt the most terrible sadness because it was not the way I expected to die. It was just foolish. ... And I was not quite ready to die. There were certain things that I still wanted to do" [Maxwell's italics].72 In "Billie Dyer," Maxwell pays tribute to the title character, an African American who rose from the lower middle class to the upper middle class. Billie Dyer had become one of the first prominent physicians of his race in the United States. Maxwell notes that a wealthy white Lincolnite named David Harts, Sr., formerly a Union Army captain in the Civil War, had become one of Billie Dyer's benefactors, helping to send him to medical school. Dr. Dyer was a patriot who served as a soldier for his country in World War I and then for many years served as an exemplary member of the medical profession and credit to his race. Maxwell's primary source for "Billie Dyer" was Dr. Dyer's account of his experiences in WW I titled "A Soldier's Diary," composed in 1918-19. Maxwell worked from a photocopy of a typescript that had been sent to the Lincoln Public Library of Lincoln, Illinois; but Dr. Dyer had also self published his diary (date and place of publication unknown, copies rare). Throughout Dr. Dyer's career, Maxwell says his fame grew and that he was appointed to increasingly prestigious but very demanding medical positions in Kansas City, Missouri, working himself to death as he tried to be a role model for other blacks.73 In "The Front and the Back Parts of the House," Maxwell's parents' black servant, Mrs. Harriet "Hattie" Dyer Brummel, functions as a foil from whom Maxwell comes to some unpleasant self-knowledge about his attitudes and behavior toward blacks. At the beginning of this story, Maxwell describes Mrs. Brummel's rejection of him when he greeted her and embraced her while visiting his Aunt Annette's home in Lincoln many years after he had left there and had found success in New York. Hattie had worked in Maxwell's childhood home and that of his aunt, and he recalls her fondly. He describes going to the American Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E) Church with Mrs. Brummel's mother, Mrs. Laura Dyer, also a servant in the Maxwells' home: During one of those times when my father was searching for a housekeeper and Mrs. Dyer was in our kitchen, she stopped me as we got up from the table at the end of dinner and asked if I'd like to go to church with her to hear a choir from the South. ... The church was way downtown on the other side of the courthouse square. As we made our way indoors I saw that it was crammed with people, and overheated, and I was conscious of the fact that I was the only white person there. Nobody made anything of it. The men and women in the choir were of all ages, and dressed in white. For the first time in my life I heard "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot," and "Pharaoh's Army Got Drownded," and "Were You There When They Crucified My Lord?" and "Joshua Fit de Battle of Jericho." Singing "Don't let nobody turn you round," the choir yanked one another around and stamped their feet (in church!). I looked at Mrs. Dyer out of the corner of my eye. She was smiling. "Not my brother, not my sister, but it's me, O Lord!" [Maxwell's italics] the white-robed singers shouted. The people around me sat listening politely with their hands folded in their laps, and I thought, perhaps mistakenly, that they too were hearing these spirituals for the first time.74

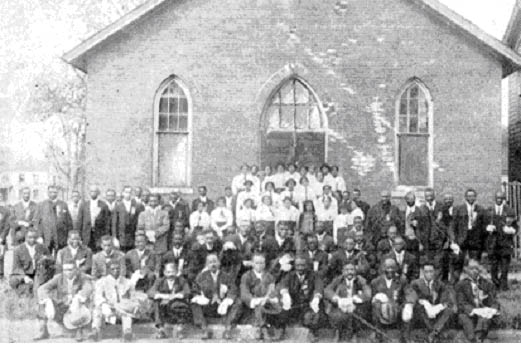

Undated photo of the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church, white-attired choir, and congregation on Broadway Street in Lincoln. This building is an enduring landmark. Source: Raymond Dooley and Ethel Welch, The First Namesake Town: A Centennial History of Lincoln, Illinois (Lincoln, Ill.: Feldman's Print Shop, 1953), 33.

Allen Chapel A.M.E. Church in

October, 2007. A.M.E. Church photos courtesy of Leigh Henson. |

|

|

|

|

|

In "The Front and Back Parts of the House," Maxwell is troubled that as he embraces Hattie, "there was no response. Any more than if I had hugged a wooden post. She did not even look at me. As I backed away from her in embarrassment at my mistake, she did not do or say anything that would make it easier for me to get from the kitchen to the front part of the house where I belonged."75

Maxwell reflects at length on

the irony of her dispassionate reaction in contrast to the

fondness that his family and he felt for her and her family.

Hattie's father and mother had diligently worked for the

Maxwells, and William's father especially liked Hattie's mother,

Mrs. Laura Dyer ("old Mrs. Dyer"), visiting her in later years

and giving her money, because she cooked and washed for him when

his wife died: "In the time of his greatest trouble, when there

was no one else he could have turned to, she didn't fail him."76 |

Laura Dyer, mother of Harriet "Hattie" Dyer Brummel. Source: Dooley and Welch, The First Namesake Town (Lincoln, Ill.: Feldman's Print Shop, 1953), 33.

|

|

As possible explanations for Hattie's coldness, Maxwell first speculates that she simply disliked whites for their insensitivity (whites thinking "they were excused from taking the feelings of colored people into consideration") and/or the crimes against blacks that Hattie may have witnessed in the race riots of Chicago.77 Yet, Maxwell senses in Hattie that her "anger was not a generalized anger; it had something to do with who I was."78 He cannot think of anything his Grandfather Blinn or his father may have done. Maxwell solicited the help of his Lincoln step-cousin, Tom Perry, who can only tell him that the local blacks did not want to talk about Hattie. Perry also mentioned his elderly black lawn keeper was reading one of Maxwell's books, "and in a flash I [Maxwell] realized what the unforgivable thing was and who had done it."79 William Maxwell's revelation is that he was responsible for Hattie's passive resistance. Specifically, Maxwell realizes that literate local blacks could very well have knowledge of his writings, and one of his novels in particular would have offended Hattie. Maxwell recalls his early novel in which Austin King is the main character, so the novel, although unnamed, is easily identified as Time Will Darken It. "The Front and Back Parts of the House" does not identify the year in which Maxwell experiences Hattie's rejection, but Time Will Darken It was first published in 1948, so this novel would have been out years and years before the rejection, giving Lincolnites–regardless of color–plenty of time to have read and discussed it. Maxwell surmises that his fictional portrayal "had exposed their [Hattie and her husband's] married life and blackened his character in order to make a fortune from my writing. ... I do not feel it is a light matter. Any regret for what I may have made Hattie feel is nowhere near enough to have appeased her anger. She was perfectly right not to look at me, not to respond at all, when I put my arms around her."80