Jewish

cemeteries are documents of history. As such they often mirror the

culture of the time—they invite to linger and to observe. A Jewish

burial ground and its planning has always been one of the first

obligations for a Jewish community after

establishing themselves in a town or village. That cemetery was

hallowed ground, to be kept in perpetuity.

At the economic height of the Jewish community’s life, in 1854, Schneidemühl’s second Jewish cemetery was consecrated. The new grounds were an extension to the earlier, older burial ground that lay immediately adjacent. The combined area measured no more than 8,000 square meters and was a level flat rectangle, unlike the sloping grounds one usually encounters in cemeteries.

In Schneidemühl of the nineteenth century, the path from the living to the realm of the departed was unusually short, located no further than a fifteen-minute walk from the vicinity of the synagogue. It was fortuitous for the community that, at the time of the town's first great fire, more than 300 years ago, the crown had allotted the Jewish community land for a burial site. In 1626 the area was surrounded by empty fields and meadows, a fair distance from the nearest habitations.

For a Jewish community to own that relatively small parcel of land, not too far from the town’s perimeter, was fairly unusual at the time and in stark contrast to the locations of European Jewish cemeteries in general. Commonly, kehilloth had to purchase their burial sites with substantial difficulties and at great costs.

Beyond the entrance with its wrought iron gate, one arrived at the house of the chazzan and at the Beth Tahará, the house of purification, variously known as Friedhofshalle, Trauerhalle or Leichenhalle, serving as mortuary where the deceased could be prepared for burial. The old cemetery had a slight rise in the center, where a few old gravestones from the Polish period of Schneidemühl had remained. In the years after the First World War the gravestones’ writing was no longer decipherable, nor were the old graves distinguishable.

In keeping with Jewish law, a tall brick wall had surrounded the old and new sections of the cemetery to prevent desecration and damage to its graves by outsiders. (For some of the town’s gentile youngsters, however, the wall presented more of a challenge than a deterrent.)

Rich in vegetation in later years, there one found birch, poplar and beech, and wild ivy gave many a grave the dignity it deserved. The cemetery’s orderly division into neat rectangular fields can be viewed as early attempts to emulate the customs and conventions of the community’s Prussian Gentile neighbors.

The earliest burial date recorded was that of Meyer b. David Baer who was laid to rest in field III. He had died on Thursday, 23 November 1854 (2 Kislev 5615) and, contrary to most other names, we know nothing else about him or his lineage. Separation of burials for men, women or children was not evident in surviving records, hinting that at least since the newer sections of the grounds were in use, the community did not adhere to strict Orthodox burial rites.

Strict Jewish custom allows no display of pomp on its matzevot, its gravestones. While Jewish gravestones used to lie flat on the ground in cemeteries before the Middle Ages, and epitaphs were only in Hebrew, in the course of the following centuries markers were placed upright and inscriptions became longer and more eulogistic; in the nineteenth century the vernacular began to feature more often.

Today, these few extant photographs give us but a glimpse of this once beautiful cemetery. An example of an epitaph with elaborately rhymed text, embodying an acrostic, was that of Louis Kronheim, father of the community's popular house doctor Emil Kronheim.

At the economic height of the Jewish community’s life, in 1854, Schneidemühl’s second Jewish cemetery was consecrated. The new grounds were an extension to the earlier, older burial ground that lay immediately adjacent. The combined area measured no more than 8,000 square meters and was a level flat rectangle, unlike the sloping grounds one usually encounters in cemeteries.

In Schneidemühl of the nineteenth century, the path from the living to the realm of the departed was unusually short, located no further than a fifteen-minute walk from the vicinity of the synagogue. It was fortuitous for the community that, at the time of the town's first great fire, more than 300 years ago, the crown had allotted the Jewish community land for a burial site. In 1626 the area was surrounded by empty fields and meadows, a fair distance from the nearest habitations.

For a Jewish community to own that relatively small parcel of land, not too far from the town’s perimeter, was fairly unusual at the time and in stark contrast to the locations of European Jewish cemeteries in general. Commonly, kehilloth had to purchase their burial sites with substantial difficulties and at great costs.

Beyond the entrance with its wrought iron gate, one arrived at the house of the chazzan and at the Beth Tahará, the house of purification, variously known as Friedhofshalle, Trauerhalle or Leichenhalle, serving as mortuary where the deceased could be prepared for burial. The old cemetery had a slight rise in the center, where a few old gravestones from the Polish period of Schneidemühl had remained. In the years after the First World War the gravestones’ writing was no longer decipherable, nor were the old graves distinguishable.

In keeping with Jewish law, a tall brick wall had surrounded the old and new sections of the cemetery to prevent desecration and damage to its graves by outsiders. (For some of the town’s gentile youngsters, however, the wall presented more of a challenge than a deterrent.)

Rich in vegetation in later years, there one found birch, poplar and beech, and wild ivy gave many a grave the dignity it deserved. The cemetery’s orderly division into neat rectangular fields can be viewed as early attempts to emulate the customs and conventions of the community’s Prussian Gentile neighbors.

The earliest burial date recorded was that of Meyer b. David Baer who was laid to rest in field III. He had died on Thursday, 23 November 1854 (2 Kislev 5615) and, contrary to most other names, we know nothing else about him or his lineage. Separation of burials for men, women or children was not evident in surviving records, hinting that at least since the newer sections of the grounds were in use, the community did not adhere to strict Orthodox burial rites.

Strict Jewish custom allows no display of pomp on its matzevot, its gravestones. While Jewish gravestones used to lie flat on the ground in cemeteries before the Middle Ages, and epitaphs were only in Hebrew, in the course of the following centuries markers were placed upright and inscriptions became longer and more eulogistic; in the nineteenth century the vernacular began to feature more often.

Today, these few extant photographs give us but a glimpse of this once beautiful cemetery. An example of an epitaph with elaborately rhymed text, embodying an acrostic, was that of Louis Kronheim, father of the community's popular house doctor Emil Kronheim.

.

(Photo courtesy M. Cohen, USA)

Hebrew inscriptions on grave stone of Louis Kronheim (centre)

Below, the Erb-Begräbniss,

a family grave, of Salomon and Ernestine Simonstein differed from a

traditional burial site. Salomon

Simonstein had died in 1904 at the age of fifty-six; his widow

Ernestine, née Lösser, was laid to rest there beside him a

quarter of a

century later in 1929. The slender but ornate wrought-iron enclosure,

laid out in the Art Nouveau style of the day with its love for natural

forms, defined the perimeter of these graves. Facing the

graveside were the traditional Hebrew inscriptions with the dates and

name of the deceased’s father.

.

(Photo courtesy M. Cohen, USA)

Hebrew inscriptions on grave

markers

of

Salomon and Ernestine Simonstein, née Lösser

Salomon and Ernestine Simonstein, née Lösser

.

(Photo courtesy M. Cohen, USA)

Facing the opposite direction, the reverse showed the German

inscriptions on grave markers of Salomon and Ernestine Simonstein,

née Lösser, — plainer and less detailed, alluding to liberal burial influences.

(Photo courtesy M. Cohen, USA)

Facing the opposite direction, the reverse showed the German

inscriptions on grave markers of Salomon and Ernestine Simonstein,

née Lösser, — plainer and less detailed, alluding to liberal burial influences.

.

(Photo courtesy M. Cohen, USA)

German inscriptions on

gravestone of

Sarah Jacob,

née Lösser

.

(Photo courtesy Henny Nossig, née Simonstein, Brazil)

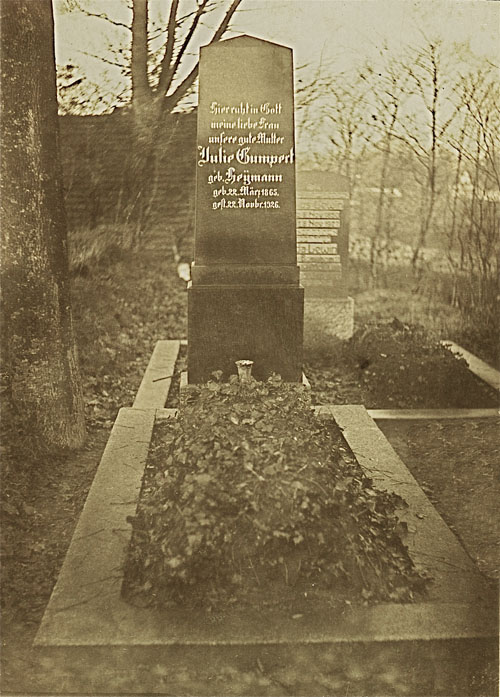

German inscriptions on grave stone of Julie Gumpert, née Heymann

.

(Photo courtesy Henny Nossig, née Simonstein, Brazil)

German inscriptions on grave stone of

Moritz Simonstein and his second wife Henriette, née Lewin

.

(Photo courtesy J. Rosenberg, Chile)

Graves of Jacob and Bertha Rosenberg, née Simonstein

These photographs are but

some of the precious few remaining witnesses to the existence of the

once fine Jewish cemetery of

Schneidemühl. Some emigrants

had the foresight to photograph a number of the graves of their immediate families before immigrating

to the United States in 1935.

Beholding

these photos nearly seventy years later, one can sense the

sentimentality expressed by those who used to visit there

regularly—they knew the language of the gravestones, they knew that the

cemetery was the collective memory of the community.

The razing of the cemetery points directly to the fierce anti-Semitic climate that had prevailed in Schneidemühl during the late 1930s. Even the community’s dead were not safe from the Nazis and the town's denizens' hatred and contempt that knew few limits.

The cemetery’s desecration was one of the town’s Nazis’ last and particularly spiteful, despicable acts toward the town's Jewish community. On 6 March 1939, the break-up of the high cemetery wall began. Thereafter, the graves of twelve generations of the Jewish community were obliterated, the gravestones plundered by the town's people.

Many stones were recycled as tombstones for other cemeteries, others were used for profane purposes—a travesty reminiscent of events in the Middle Ages and the Crusades.

As one witness recalled decades later: “… the Jewish cemetery was soon flattened and turned into a park with flowerbeds and benches for the public. Now only the strong tall trees bear witness to the old times.”

The razing of the cemetery points directly to the fierce anti-Semitic climate that had prevailed in Schneidemühl during the late 1930s. Even the community’s dead were not safe from the Nazis and the town's denizens' hatred and contempt that knew few limits.

The cemetery’s desecration was one of the town’s Nazis’ last and particularly spiteful, despicable acts toward the town's Jewish community. On 6 March 1939, the break-up of the high cemetery wall began. Thereafter, the graves of twelve generations of the Jewish community were obliterated, the gravestones plundered by the town's people.

Many stones were recycled as tombstones for other cemeteries, others were used for profane purposes—a travesty reminiscent of events in the Middle Ages and the Crusades.

As one witness recalled decades later: “… the Jewish cemetery was soon flattened and turned into a park with flowerbeds and benches for the public. Now only the strong tall trees bear witness to the old times.”

.

(Photo P. S. Cullman, Canada)

"Beware of well-kept lawns!"

In the renamed Polish town of Piła, this is what remains today of the

one-hundred-and-fifty-year old cemetery that used to belong to

the former Jewish community of Schneidemühl.

Fourteen generations lie buried here.

(Some of the above material has been excerpted from the recently published book

History of the Jewish Community of Schneidemühl: 1641 to the Holocaust)