| Lange, ed. | Moment's Notice: Jazz in Poetry & Prose (1993) |

| Lees | Cats of Any Color: Jazz Black and White (rpt 2000; 1995) |

| Lees | Meet Me at Jim & Andy's (rpt 1990; 1988) |

| Litweiler | Ornette Coleman: A Harmolodic Life (rpt 1994; 1992) |

| McCarthy et al. | Jazz on Record: A Critical Guide to the First 50 Years, 1917-1967 (1968) |

| Maggin | Stan Getz: A Life in Jazz (1996) |

| Milkowski | Jaco [Pastorius] (1995) |

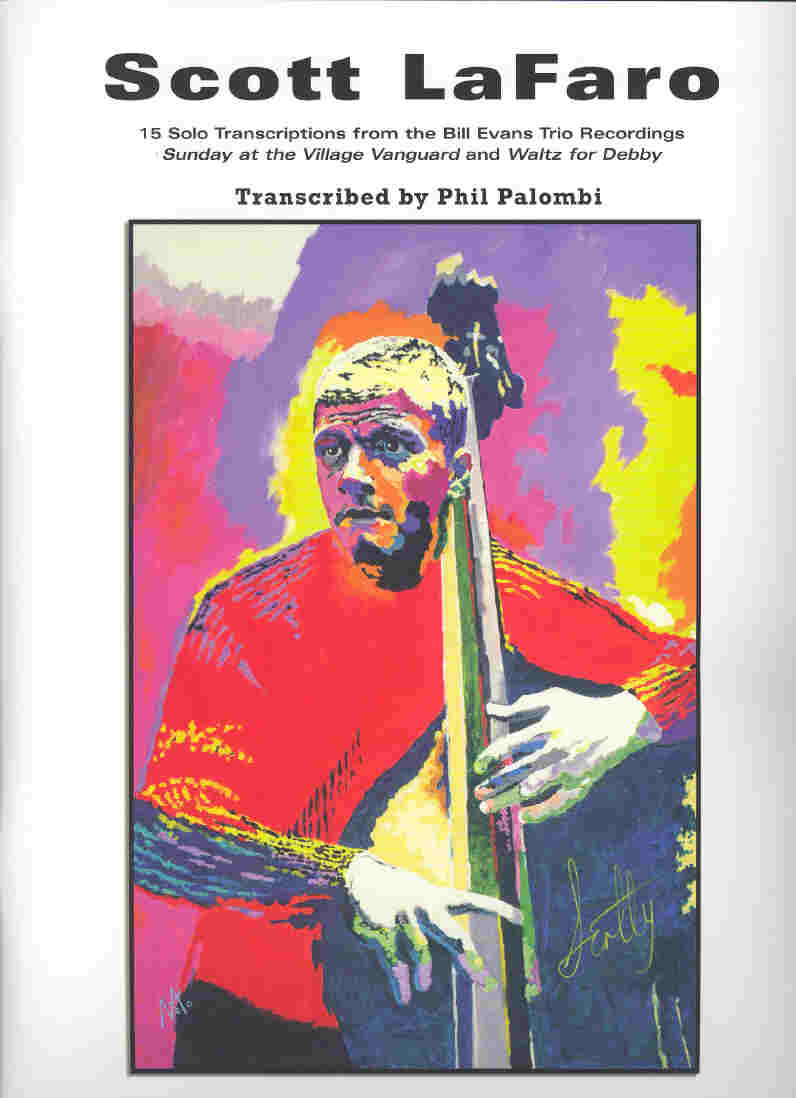

| Palombi | Scott LaFaro: 15 Solo Transcriptions . . . (2003) |

| Pettinger | Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings (1998) |

| Pleasants | Serious Music And All That Jazz (rpt 1971; 1969) |

| Porter | John Coltrane: His Life and Music (1998) |

Lange, Art and Nathaniel Mackey, eds. Moment's Notice: Jazz in Poetry and Prose. Minneapolis, MN: Coffee House Press, 1993.

Includes the poem "To the Pianist Bill Evans" by Bill Zavatsky (pp. 285-287), with allusions to LaFaro and to the automobile accident which ended his life but not his music. Poem was published first in Bill Zavatsky, Theories of Rain and Other Poems (New York: Sun, 1975). Full text of this poem will be found in the entry for Zavatsky's Theories of Rain (below).

Lees, Gene. Cats of Any Color: Jazz Black and White. [Cambridge, MA and New York, NY:] Da Capo Press, 2000. First published by Oxford University Press, 1995. "Introduction copyright 2001 by Gene Lees" (verso title page).

"The essays in this book first appeared, some of them in somewhat different form, in the Jazzletter, PO Box 240, Ojai, CA 93024-0240. This is the fourth collection of pieces from the Jazzletter to be published by Oxford University Press." ('Acknowledgements', p. vii)

Scott LaFaro is mentioned in several contexts:

At p. 16: Following Lees' description of growing up in Ontario, Canada, not far from Buffalo, NY, a "creature of the Great Lakes" (p. 7), becoming a newspaper reporter, moving in 1955 to Louisville, KY, and then in 1958 to Paris, France on a fellowship, returning in 1959 to New York to become the editor of Downbeat (until 1961), he lists "all sorts of black friends and acquaintances . . . and a lot of white friends, too. I met Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond then, and Phil Woods, Bill Evans, Gerry Mulligan, Scott LaFaro, Woody Herman, Zoot Sims. One day it struck me that since Louis Armstrong was still alive, I had met, and in many cases knew well, most of the great jazz musicians who had ever lived."

At p. 162: In the essay, "The Return of Red Mitchell", Mitchell in conversation with Lees, about Mitchell's experimenting with tuning the double bass as a cello (that is, changing from the 4-string E-A-D-G 'fourths' intervals of the double bass to the four-string C-G-D-A 'fifths' intervals of the cello but an octave lower), says:

'Gary Peacock and Scott LaFaro were both protégés of mine. I remember one session particularly in East L.A. when I showed them both this two-finger technique, which I had worked out in 1948 in Milwaukee, on the job, there with Jackie Paris.' Red was referring to the alternating use of the index and middle finger on the right hand to pull the strings.

At p. 179: In the essay, "Three Sketches" at its part 3, 'Jack in the Woods' with comments of drummer Jack DeJohnette:

"I guess the concept of the bass the way Scott [LaFaro] played it was not so much unusual -- people like Mingus were playing with the fingers before Scotty was discovered, " Jack said. "You had Jimmy Blanton. I think had Danny Richmond been a different kind of drummer, he might have had the kind of interplay with Mingus that you got with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian. People like Gary Peacock might have pre-empted that. That combination of Bill, Paul, and Scotty shifted the emphasis of time from tow and for. The way Paul broke up the time. He played sort of colored time rather than stated time. As opposed to what Miles would do. So that they made it in such a way that when they did go into four-four, it was kind of a welcome change. Then they'd go back into broken time."

"I remember the effect it had on rhythm sections in Chicago, because I was at the time a pianist, playing with a bassist who also played cello. We would sit up nights late, listening to the trio records. I noticed the rhythm sections in Chicago started playing that way. So I saw that influence start happening, where the time was broken up."

At p. 214, in the essay "Jazz Black and White" in context of Gene Lees' comments on the book, Miles: The Autobiography:

Quoting Miles Davis lamenting pianist Bill Evans's departure from Davis's 1958 quintet: "It's a strange thing about a lot of white players -- not all, just most -- that after they make it in a black group they always go and play with all white guys no matter how good the black guys treated them. Bill did that, and I'm not saying he could have gotten any black guys any better that Scott (LaFaro) and Paul (Motian), I'm just telling what I've see happen over and over again.'

Lees says that this is nonsense. Evans made his first trio album New Jazz Conceptions as leader in 1956. His next trio LP, Everybody Digs Bill Evans with Sam Jones on bass and Philly Joe Jones on drums. Moreover, Miles hired Evans back in April 1959 to record Kind of Blue.

Note: Helen LaFaro-Fernandez has a post card sent to her brother by Miles Davis. The image on the card is a black and white caricature of various instrumentalists. Davis asks LaFaro in his note: "Hey man, where's the bass?"

Lees, Gene. Meet Me at Jim & Andy's: Jazz Musicians and their World. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. (OUP paperback edition, 1990)

"All the material in this book [with the exception of the portrait of Bill Evans] appeared originally in the Jazzletter, a publication I founded in 1981. . ." (pp. xvii-xviii of the Introduction)

From the essay, "The Poet: Bill Evans" (pp. 142-175):

Something happened in the two years between New Jazz Conceptions (September 1956) [Evans's first recording under his own name] and Everybody Digs [Bill Evans] (December 1958): Bill found his way into the heart of his own lyricism. After that Bill formed a standing trio, with bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian, with which group Orrin Keepnews produced a series of Riverside albums that continue one of the most significant bodies of work in the history of jazz.

Bill wanted it to be a three-way colloquy, rather than pianist-accompanied-by-rhythm-section. And it was. LaFaro, still in his early twenties, had developed bass playing to a new level of facility. He had a gorgeous tone and unflagging melodicism. Motian, Armenian by background, had since childhood been steeped in a music of complex time figures and was able to feed his companions patterns of polyrhythm that delighted them both.

Pianists waited for their albums to come out almost the way people gather at street-corners in New York on Saturday night to get the Sunday Times: Portrait in Jazz, Explorations, and the last two, Waltz For Debby and Sunday at the Village Vanguard, derived from afternoon and evening sessions recorded live on June 25, 1961. These albums alone (which are best heard in the compact-disk reissue from fantasy, which have superb sound), if Bill had never recorded anything else, would have secured his position in jazz. Indeed, his solo on John Carisi's tune 'Israel', a soaring flight of breath-taking melodic invention, which is in the Explorations album, would almost have done that. There is a deep spirituality in those Riverside albums, the more astounding when you realize that Bill was at that time sinking into his heroin addiction, to Scott LaFaro's helpless dismay. If you look at the album covers in sequence, you find Bill's face getting thinner. (145-146)

. . .

When he [Bill] was you, he looked like some sort of sequestered and impractical scholastic. There is a heartbreaking photo of him on the cover of the famous Village Vanguard recordings, made for Riverside in the early summer of 1961. Whether that phot was taken before or after the grim fiery death of Scott LaFaro in an automobile accident ten days after the sessions, I do not know. But there is something terribly vulnerable and sad in Bill's young, gentle, ingenuous face. I knew Scott LaFaro only slightly, through Bill, and I didn't like him. He seemed to me smug and self-congratulatory. But he was a brilliant bass player, as influential on his instrument as Bill was on his, and Bill always said LaFaro was not at all like that when you got past the surface, which I never did. The shock of LaFaro's death stayed with Bill for years, and he felt vaguely guilty about it. This is not speculation. He told me so. He felt that because of his heroin habit he had made insufficient use of the time he and Scott had had together. LaFaro was always trying to talk him into quitting. After LaFaro's death, Bill was like a man with a lost love, always looking to find its replacement. He found not so much a replacement of LaFaro as an alternative in the virtuosic Eddie Gomez, who was with him longer than any other bassist. (p. 147)

Note: Lees captures a fundamental truth about Evans and LaFaro's musical and personal relationship. It was spiritual and it was loving. It is in their music. The other essays in this book are portraits of the artists: Duke Ellington, Artie Shaw, Woody Herman, Frank Rosolino, bassist John Heard (the painter); Paul Desmond, Art Farmer, Billy Taylor.

Litweiler, John. Ornette Coleman: A Harmolodic Life. New York: Da Capo Press, 1994. "First Da Capo Press edition 1994" An unabridged republication of the edition published in New York in 1992, by arrangement with William Morrow & Company.

Litweiler explores the interplay among Ornette Coleman and his "collaborators" as he says. He recognizes the forceful personalities of both Coleman and LaFaro and poses the question that many have asked, namely, what might have happened had these two inventive and original musicians worked more with each other.

p. 98 "There's no way of knowing whether additional experience in the quartet would have furthered the integration of Scott LaFaro's music, or how his and Ornette's forceful musical personalities might have gone on to affect one another; for the group did not perform again that winter [of 1960-1961], and soon LaFaro was working with Evans again. Six months after Ornette! LaFaro died tragically in an automobile accident. Meanwhile, Ornette replace him with Jimmy Garrison, and this Ornette Coleman Quartet recorded Ornette on Tenor in March [1961]."

p. 95 "For Free Jazz [Eric] Dolphy again chose to play bass clarinet, and Ornette's other collaborators on the recording's 'double quartet' were his latest quartet partners, [Don] Cherry, LaFaro, and [Ed] Blackwell; his former bassists and drummer, [Charlie] Haden and [Billy] Higgins; and Dolphy's roommate, young trumpeter Freddie Hubbard . . ."

p. 96 "January [1961] found the Ornette Coleman Quartet back at the Village Vanguard for two weeks, and then into the recording studio for the Ornette! session. Changes in Ornette's music were now quite evident, the most obvious being the abandonment of lingering links to material based on standard chord changes ('Embraceable You' had been the last) and the replacement of Charlie Haden's close empathy by Scott LaFaro's virtuoso accompaniments. Upon coming to New York in 1959, LaFaro joined the Bill Evans Trio at something near the pianist's peak. Apart from his work with Ornette, much of LaFaro's reputation rests on his gradually claiming the role of central voice in the Evans Trio. LaFaro was a strong player, possibly even as forceful as Haden, but his technical facility and his harmonic choices often made his lines appear merely ornamental, whereas Haden's had been integral. Thus much of this particular quartet's music leaves the effect of brilliant rhythmic interplay between Ornette and Blackwell, joined by brilliant and decorative bass."

pp. 96-97 "About LaFaro's personality, Ornette once said, 'He felt superior not only to Negroes but to whites as well," [footnote #29] while Haden remembers, 'I'd come home and Scotty would be on the bed, upset, saying, 'I'll never be good enough.' He was a perfectionist, though. I'd tell him how great he was, but he wouldn't be satisfied.' [footnote #30] These seemingly disparate attitudes about himself, far from being mutually exclusive, seem to be opposite sides of the same coin."

p. 97 "The most integrated work at the session was the fastest, 'The Alchemy of Scott LaFaro,' with quite fiery playing by Ornette and his bassist. 'T and T' is an excellent, West African-inspired drum solo-- Blackwell by then was already an experienced student of international percussion cultures--while the other three works originally released in Ornette! are all in a similar tempo and feature, for a change, extended soloing. The most remarkable performance, 'W.R.U.,' is slightly faster than the others, at a medium -fast pace that's an ideal stimulus to Ornette's eight-minute solo, which from a thrilling beginning moves through a world of vibrant melody, constantly challenged by Blackwell's ingenious rhythms; LaFaro's bass solo, with 'twisting sitar-like glissandos and double stops,' [footnote #31] is excellent, thought largely unrelated in mood to the rest of the performance. 'C and D' includes a similarly fine bowed-bass solo, this one suggestive of a classical music sensibility, while 'R.P.D.D.' is almost entirely a strong Ornette solo."

pp. 213-214 Litweiler provides a Coleman discography. which on these two pages, lists the Coleman sessions that included LaFaro:

December 19, 1960

New York CityGunther Schuller Orchestra

Ornette Coleman (as)

Jim Hall (g)

Alvin Brehm (b)

Scott LaFaro (b)

Sticks Evans (d)

The Contemporary String Quartet:

Charles Libove (violin)

Roland Vamos (violin)

Harry Zaratzian (viola)

Joseph Tekula (cello)

Gunther Schuller (conductor)

'Abstraction' (Schuller) Atlantic SD 1365

Note: This ensemble, minus Coleman, recorded Jim Hall's 'Piece for Guitar and Strings' at this session.

December 20, 1960

New York CityGunther Schuller Orchestra

George Duvivier replaces Brehm

add Eric Dolphy (as, fl, bcl)

Robert DiDomenica (fl)

Eddie Costa (vibes)

Bill Evans (p)

'Variants on a Theme of Thelonious Monk' ('Criss Cross') (Schuler) Atl SD 1365

Note: This ensemble, minus Coleman, recorded Schuler's 'Variants on a Theme of John Lewis (Django)' at this session.

December 21, 1960 Ornette Coleman Double Quartet

Don Cherry (pocket trumpet)

Freddie Hubbard (trumpet)

Ornette Coleman (alto sax)

Eric Dolphy (bass clarinet)

Charlie Haden (bass)

Scott LaFaro (bass)

Billy Higgins (drums)

Ed Blackwell (drums)

'First Take (Free Jazz)' Atl SD 1588

'Free Jazz' Atl SD 1364January 31, 1961 Ornette Coleman Quartet

Don Cherry (pocket trumpet)

Ornette Coleman (alto sax)

Scott LaFaro (bass)

Edward Blackwell (drums)

'W.R.U.' Atl SD 1378

'Check Up' Atl SD 1588

'T. & T.' Atl SD 1378

'C. & D.' Atl SD 1378

'R.P.D.D.' Atl SD 1378

'The Alchemy of

Scott LaFaro' Atl SD 1572

McCarthy, Albert [and others]. Jazz on Record: A Critical Guide to the First 50 Years, 1917-1967. New York: Oak Publications, 1968. Pp. 51, 95, 100.

At p. 95: Re: Explorations -- “This was in no way 'piano with rhythm accompaniment' for LaFaro's surging bass lines achieved unbelievable prominence at times.” [and]

“LaFaro was a difficult man to replace for he was a strong individualist and, in his way, almost as revolutionary a pioneer as was Jimmy Blanton.” Commentary by 'A.M.' [Alun Morgan]

Maggin, Donald L. Stan Getz: A Life in Jazz. New York: W. Morrow, 1996. “First Quill Edition”

Passim: 178, 189, 196, 198, 199, 205, 219, index 413.

At p. 178 – Re: LP Cal Tjader -- Stan Getz (8 Feb 58). “Stan contributed more than his horn, however, as he brought along two very talented discoveries of his – drummer Billy Higgins and bassist Scott LaFaro, both twenty-one at the time.”

At p. 189. Mentions Coleman's Free Jazz recording with LaFaro.

At p. 196. Re: three recording sessions of Stan Getz arranged by Norman Granz of Verve Records. Second session (New York: February 21, 1961) included Pete La Roca, drums; Steve Kuhn, piano; and Scott LaFaro, bass. Quoting Maggin: “LaFaro, now age twenty-five, seemed to have limitless potential. His technical facility was so great that he played the bass as others would a guitar; he created subtle, propulsive variations on the beat that every subsequent bass player copied, and he had mastered all three jazz idioms: chordal, modal, and free. LaFaro had been recorded with Ornette Coleman on the Free Jazz session of December 1960 and on a quartet date a month later, had participated in several John Lewis—Gunther Schuller third stream recordings, and since early 1959 had worked in the trio of pianist Bill Evans, which produced a couple of LPs that have become jazz classics. . . On the most exciting track of the session, the fast-paced `Airegin', the pianist, Kuhn, lays out for most of Stan's multi-chorus solo, and Stan's and LaFaro's voices mesh in a scintillating rapport similar to that which Stan had achieved a decade earlier with guitarist Jimmy Rainey.”

At p. 198. On Getz's quartet playing in clubs in Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York's Village Vanguard in the spring of 1961: “The youngsters LaFaro and Kuhn, fresh from their work with Coleman and Coltrane, stimulated him with their new ideas and great skills, and the veteran Haynes proved night after night that he was one of the most imaginative percussionists in jazz.”

At p. 199. On Getz's plan to record Eddie Sauter arrangements in an album to be called Focus, scheduled for recording in late July 1961:

Stan gave LaFaro Sunday, June 25, off to make a trio recording with Bill Evans at the Village Vanguard; they created a superb album, the culmination of all the work LaFaro had done with the pianist for two years. Stan again gave LaFaro time off after a triumphant set with Stan's quartet on July 3 at the Newport/New York jazz Festival; on this occasion LaFaro drove to the small city of Geneva in the north central part of New York State to visit his mother. Stan never saw him again. LaFaro, a notoriously reckless driver, was killed instantly on July 6, 1961, at age twenty-five when his car crashed into a tree in Geneva.”

Note: Scott's sister, Helene, has taken exception to Maggin's gratuitous statement about her brother's automobile driving. Scott was not a reckless driver, according to Helene, and, in fact, did not like driving all that much. Helene recalls that in Los Angeles, she would drive her brother and Victor Feldman to and from gigs. (in conversation, 1997)

At p. 205. Re: Getz recording with Bob Brookmeyer, Getz-Brookmeyer 61, with John Neves, bassist, who replace LaFaro.

At p. 219. Re: Getz's hiring vibraphonist Gary Burton who “like earlier bright young protégés such as Horace Silver and Scott LaFaro – . . . stretched Stan's imagination.”

Milkowski, Bill. Jaco: The Extraordinary and Tragic Life of Jaco Pastorius "The World's Greatest Bass Player" San Francisco: Miller Freeman Books, 1995 (paperback edition 1996).

This book is not indexed. At p. 76 is one (indirect) reference to Scott LaFaro where Milkowski quotes from Mark C. Gridley, Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, to wit: "He [Pastorius] walks persuasively, as he proved on 'Crazy About Jazz' (contained in [the recording Weather Report] Weather Report's eleventh album, which has the same title as their first [album]) He plays in the non-repetitive, interactive way [identified by Scott LaFaro], as evidenced on 'Dara Factor One' (also on [Weather report's] eleventh album) and 'Dream Clock' ([Weather Report's] Night Passage).

Although Jaco Pastorius, christened John Francis Pastorius III (01 December 1951 -- 21 September 1987 -- aet. 35), had a meteoric rise to fame as musician and self-proclaimed "world's greatest bass player". There is no report of Pastorius having listened to LaFaro, but these two musicians are linked by way of their shared musical experience with pianist Paul Bley and trumpeter-saxophonist Ira Sullivan.

Pastorius recorded with Bley (June 1974) on an album entitled simply Pastorius / Metheny / Ditmas / Bley (Milkowski, p. 57). LaFaro played with Bley at the It Club in Los Angeles (1958) but the recording of this ensemble unfortunately was never released and the recording's tapes were lost in a warehouse fire.

Pastorius recorded with Sullivan ( ) on the latter's Ira Sullivan (Milkowski, pp. 52-53). LaFaro played, but did not record, with Sullivan when both were in Chicago in late 1957.

Palombi, Phil. Scott LaFaro: 15 Solo Transcriptions from the Bill Evans Trio Recordings Sunday at the Village Vanguard and Waltz for Debby / [edited and] transcribed by Phil Palombi. [New York] Palombi Music [ www.palombimusic.com ] 2003. ISBN 0-9747617-0-2. 60 pp.

"Copyright 2003 by Palombi Music; Editor, transcriber, copyist: Phil Palombi; Layout: Andrew Green; Cover Art: Manny Fernandez" (verso title page)

"About the Author: Phil Palombi is a professional bassist residing in New York City. His performance and recording credits include such players as Toshiko Akiyoshi, Michael Brecker, Maynard Ferguson, Billy Hart, Etta Jones, Dave Liebman, Chris Potter, Claudio Roditi, Curtis Stigers, Lew Tabackin, Mark Turner, the Village Vanguard Orchestra, Chucho Valdes, and Walt Weiskopf.

Phil has recorded his first project as a leader, 80 East, which showcases his composing talents as well as his playing. The twelve-track disc features the all-star line-up of Harold Danko, Joe LaBarbera, and Walt Weiskopf. For more information please refer to Phil's website: www.philpalombi.com " (p. [3])

"Due to the complex nature of copyright laws, I am unable to publish the titles of the songs. I have left spaces where they can be written in. Since Scott's solos are so distinctive, this shouldn't be too difficult. However, if you have any questions, please feel free to email me through my Web site. (from the "Table of Contents", p. 7)

"Scott LaFaro is a monumental figure in the evolution of the bass and its role in jazz. He had a great sense of time and melody, as well as incredible facility on the instrument. Scott is probably best known for his solos and his 'loose' accompany style on the Bill Evans recordings Waltz for Debby and Sunday at the Village Vanguard [recorded in New York 25 June 1961], but that is only part of his story. He also had a reputation as a solid bassist who could really lay it down.

. . .

Scott liked to use the full range of the instrument when he improvised. To get into the upper register, he would often run up the G string, preferring to finger the octave G, rather than use the harmonic. He hit the jazz world with a new sense of what a bass could sound like due to his innovative rhythmic and melodic ideas. Scott also had a very powerful sound. He had very strong hands, which you can hear in the way he attacked the strings with his right hand and hammered the fingerboard with his left.

Every musician, no matter how unique he or she is, has been influenced by other players at some point in their development, and Scott LaFaro is no exception. He didn't just fall to earth -- he worked hard. He had an original voice on the instrument, but as I transcribed [his] solos, I found what I believe to be a little ray Brown influence. I imagine that almost every bassist has come under ray's spell at some point in their life. As I got deeper into Scott's playing, I began to notice diminished and whole tone patterns that reminded me of things Ray talked about during a lesson I had with him. He talked in depth about using these patterns over chord changes, and had great fingerings worked out for them. It seems to me that Scott digested ray's diminished and whole tone ideas and came up with something very unique.

If you study Scott's solo on 'Solar', for instance, you will notice just how much he used diminished patterns in his playing. You may also notice how many of his note choices in this solo contradict the chord changes. When you listen to this solo, you can't hear any 'wrong notes' because pianist Bill Evans drops out after the third chorus and stays out until the end of the bass solo. . . ." (from the "Introduction" pp. 8-9)

Includes a section (pp. 10-14) on "Notation" which articulates Phil Palombi's approach to transcription of notes "between two standard pitches" and 'X' notes or ghosted notes, which occur whenever LaFaro shifts position. It discusses other techniques known to bassists as "hammer-on, pull-off, and slide." (p. 12)

Pettinger, Peter. Bill Evans: How My Heart Sings. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998. Both cloth and paper back editions.

One of my favorite books about the music! Pettinger, an accomplished concert pianist himself, who recorded the music of his countryman, Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934), in addition to the works of other composers, looks at Evans through his myriad recordings, in chronological sequence, examining themes, harmonies, even the quality (or lack thereof) of the pianos that Evans played. Pettinger, who listened to Evans at Ronnie Scott's jazz club in London, but could not muster the courage to approach the jazz master to talk shop, tragically died prior to the fall 1998 publication of his book. With apologies to the late Mr. Pettinger, and to Yale University Press, below are some extensive quotations from the book as these describe the relation of Bill and Scott, and especially their too few recordings:

p. 90 Re: Tony Scott's 1959 (released 1986) recording Sung Heroes, "the session marked the first studio collaboration of what was to become a historic threesome: Bill Evans, Paul Motian, and a twenty-three-year-old bassist named Scott LaFaro. 'Misery', written by Tony Scott for Billie Holiday, is a four-minute gem, a deeply poignant composition given a fabulously beautiful opening by Evans, who focuses again on his lyricism, his spiritual domain. LaFaro plays a simple line while indulging a subtle variety of attack and timing, but the melding of that line with the piano, in its placement and tone, gives the number distinction. [My emphasis] Not much happens, but a wavelength is established. For Evans, having drifted for some months, 'Misery' offered a glimpse of a relationship to come."

p. 91 Re: Evans' search for a trio that (Pettinger quoting Evans) 'will grow in the direction of simultaneous improvisation rather than just one guy blowing followed by another guy blowing. If the bass player, for example, hears an idea that he wants to answer, why should he just keep playing a 4/4 background? The men I'll work with have learned how to do the regular kind of playing, and so I think we now have the license to change it. After all, in classical composition, you don't hear a part remain stagnant until it becomes a solo. There are transitional development passages--a voice begins to be heard more and more and finally break into prominence.' [footnote #7]

p. 91 "Evans, with some help from Miles Davis, began to search for the right fit of trio members in November 1959, first, at the newly-named Basin Street East club with bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Kenny Dennis, then with drummer Philly Joe Jones. As Evans said, "I went through four drummers and seven bass players . . . during that gig." [footnote #6] One of the bassists who sat in with Evans during the Basin Street East gig was Scott LaFaro who had been working nearby in a duo."

p. 92 "He [Evans] knew that if the stereotyped mold could be broken, beautiful music could be created. He was also conscious that he wanted to develop this ideal, not as a solo pianist, but with colleagues of like mind. Paul Motian had been on his wavelength for years, and now -- Eureka! -- Scott LaFaro was in the running as an equal voice." The new trio landed an extended engagement at the Showplace, and by a process of trial and error began to develop the group concept on the job. 'All I had to offer,' said Evans, 'was some kind of reputation and prestige that enabled me to have a record contract, which didn't pay much, but we could make records -- not enough to live on, but enough to get a trio experienced and moving. I found these two musicians were not only compatible, but would be willing to dedicate themselves to a musical goal, a trio goal. We made an agreement to put down other work for anything that might come up for the trio.' [footnote #8] The members formed, briefly, as it tragically turned out, one of the most important, one of the best-knit, and one of the most subtly inventive groups ever to exist in music."

p. 92 "When he [LaFaro] came to New York in April 1959, he toured briefly with Benny Goodman (ironically, in view of the Basin Street episode) before meeting up with Evans on Sung Heroes."

p. 93 Re: Recording of Portrait in Jazz: ['Periscope'] was the first number to be recorded, and LaFaro immediately homed in on the pianist in a special way. When Evans breathed between phrases for a bar or so, LaFaro filled in with a plunging line, the sound ample and resilient. Significantly, at such moments, the bassist had taken the initiative for propelling the performance as a whole; he was already an equal partner. His choice of notes on a walking bass was intriguingly unconventional, and an infectious swing was generated by all three players in rapport."

p. 92-93 "Maintaining the medium-tempo feel, 'Witchcraft' was next up. LaFaro created all manner of patterns from note one; during the first four bars alone he had climbed a ladder to dizzy heights, in sequences that sound roughly like triplets but are actually resolved in a quite independent meter. This sort of strategy bore out some remarks Evans made later: ' . . . that he was a marvelous bass player and talent [ed], but it was bubbling out of him almost like a gusher. Ideas were rolling out on top of each other; he could barely handle it. It was like a bucking horse.' [footnote #10]

p. 94 ". . . Elsewhere on [Portrait in Jazz], never satisfied, [LaFaro] can be heard trying out chording, a procedure made easier by the way his bass was strung: by lowering the height of the bridge, he brought the strings closer to the fingerboard than was the norm, making possible a more guitarlike technique. This unfailing enthusiasm for experiment was just what Evans wanted -- it was vital to his concept of interaction between the players. After the theme of 'Witchcraft' both players soloed in tandem, Evans initially dropping in and out of short phrases to allow LaFaro into the dialogue. The concept was beginning to work. The pianist's invention on these two tracks, with its instant execution, was staggering, the ideas direct and clear."

p. 94 "The notion of 'simultaneous improvisation,' incorporating call and response, emerged as planned procedure on two versions of 'Autumn Leaves.' One take (on which the stereo equipment was malfunctioning) was put on the mono release, the other on the stereo. On the mono 'preferred version' Paul Motian was a brilliantly equal third partner, and when the launch came he provided exhilarating drive. Equally, an up-tempo 'What Is This Thing Called Love?' demonstrated some formally planned interplay, as well as tight piano-and-drums riffing behind the bass solo, evolved during their Showplace club engagement. Evans's main solo was a joy and it is no exaggeration to say that the presence of Scott LaFaro had given him a new lease on exploratory life. Perhaps for the same reason, the pianist was inspired on ballads to erupt from his lyrical base into ecstatic flights of energy as though, childlike, he was unable to contain his wonderment."

p. 99 "From March to May [1960, the Bill Evans Trio was] featured on several early-hours transmissions from Birdland. In the early 1970 excerpts from these broadcasts came out on two bootleg LPs. The labels were Alto Records (A Rare Original) and Session Records (Hooray for Bill Evans Trio), just two in a huge series released by New York record collector-turn-executive Boris Rose.

. . .

p. 99 "In 1992 Cool n' Blue Records of Switzerland reissued this material on CD as The Legendary Bill Evans Trio: The 1960 Birdland Sessions. In addition to the material on the LPs, this release included closing-theme ('Five') tags and the restored MC Sid Torin's voice introducing 'the most talked about young man of piano jazz' and plugging the just-issued Portrait in Jazz. These were the Friday night editions of the Symphony Sid Show, running until five in the morning, with phone-in record requests invited. The trio sets went out live between midnight and on o'clock -- hence the Saturday dates listed."p. 99 "On the transmission of April 30, LaFaro introduced a new feature into 'Autumn Leaves,' namely a pedal note on the first sixteen bars, and he structured his first solo chorus correspondingly. Such pedal points were ripe for development in Evans' playing, too, and increasingly of late the last two bars of a theme statement (the 'turnaround') had received special special treatment. In the vast majority of songs, the last note of the melody falls on the first beat of these two link bars. Evans understood the true function of this breathing space (literally so, if the melody is being sung), and foresaw how anticipation of the first solo could be heightened by exploiting the insistent pull of the dominant. By encouraging his bass player to set up a reiterated dominant pedal note against the harmonies that revolved back to the tonic, he propelled the listener from the end of the tune into the improvising.

p. 99 "Increasingly, the first solo was coming from LaFaro. That night he was in an extroverted mood, strumming his instrument like a guitar and violently rattling gut on fingerboard. On 'Come Rain or Come Shine' his forging line pounded into the very earth. Evans always got straight down to business on this song, worrying away at the chords, wrenching them this way and that.

p. 104 "The trio reunited for a New Year's tour of the Midwest. At the end of the tour, in February 1961, they made a second album for Riverside called Explorations. According to Orrin Keepnews, there was tension in the air on the recording date. Evans and LaFaro were at loggerheads over some nonmusical matter, and Keepnews was fed up with their bickering. . . . LaFaro was grappling with a replacement bass while his usual Vermont-made instrument was being repaired. As a result he was shy of the high register and indulged less than usual in his personal brand of chordal experiment. . . . [T]here is a feeling of restraint in the trio's playing--an exploration of an elegant sound-world dedicated to the understatement. . . ."

p. 106 "Evan's achievement lay in consolidation, in the creation of a self-sufficient left-hand language--a 'voicing vernacular' peculiarly his own--based on the logical progression of one chord to the next while involving the minimum movement of the hand. This resulted in a continuity of sound in the middle register (still implied even when momentarily broken) that opened up areas for invention not only above but below it. The pianist's left hand spent much of its time around middle C, a good clean area of the piano where harmonic clusters are acoustically clearest. Thus was paved the way for the bass player's contrapuntal independence, an opportunity seized by Scott LaFaro."

p. 110 "Night after night at the Vanguard, Bill, Scott LaFaro, and Paul Motian honed their craft and refined their art. They were obviously in superior shape, and Orrin Keepnews pressed Evans to make his first on-the-job recording. . . . Evans liked [the Vanguard's] forty-year-old Steinway . . . The Vanguard's policy at that time was to schedule a Sunday matinee as well as an evening performance, and those afternoon sessions . . . were a focus for the most discerning jazz audience in New York City. On June 25, 1961, the trio played five sets -- two in the afternoon and three in the evening -- each one comprising four or five numbers and lasting about half an hour. The long day afforded the Riverside team generous leeway for whatever recording hazards might arise on site. . . . Two Albums resulted at the time: Sunday at the Village Vanguard and Waltz for Debby . . . "

p. 111 [The first set] included one new number, 'Alice in Wonderland,' [which] evinced [Evans'] fondness for the Disney waltz, his delivery at once floating, lithe, and tensile. Another recorded first for him was 'My Foolish Heart,' from the 1949 film of tat name. In the movie, Victor Young's full-bloodied [sic, in recté, full-bodied] score conveyed the love-theme as a leitmotiv, the melody welling up under every kiss. Here at the Vanguard, Evans's glowing ballad statement sustained a cooler romanticism, quintessentially his own. This sublime reading, the corporate sound unerringly molded, stands as one of the all-time classic Bill Evans Trio tracks."

p. 111 "In the second set 'My Romance' was alive in detail, yet serene in progression, a feeling helped by LaFaro's emphasis on a half-note, rather than a quarter-note, pulse. . . . The afternoon ended with 'Solar' by Miles Davis, Evans's solo starting as a long, octave-doubled single line, parallel fingers flashing in all manner of rhythmic guise. Scott LaFaro resolutely refused to 'walk' but improvised alongside, the duo tied together by Paul Motian's intertwining pulsations. Thus provoking astonishment and awe, the trio closed down until the evening."

p. 111 "The evening sessions opened with LaFaro's intriguing new composition, 'Gloria's Step.' Its irregular phrase lengths feel completely natural, testimony to LaFaro's creative flair. Evans was quite at home in it with his unassumingly melodic commentary and exemplary pedaling. On 'My Man's Gone Now' the piano solo was typically understated, LaFaro's strummed underpinning responsible for the broodingly intense mood.

p. 113 ". . . The [fourth?] set ended with Evans's only recorded shot at Miles Davis's 1958 modal classic 'Milestones,' which in due course panned out as a bass feature. By now LaFaro had his Vermont-made instrument back in service after the Explorations date. When on tour, Evans had noted, 'It had a marvelous sustaining and resonating quality. He'd be playing in the hotel room and hit a quadruple stop that was a harmonious sound, and then wet the bass down on its side, and it seemed the sound just rang and rang for so long." [footnote #5]

p. 113 "The final [fifth] set reworked earlier tunes, more deeply in the cases of 'Detour Ahead' and 'Gloria's Step,' less so Waltz for Debby' and 'All of You'. It was late, it had been a long day, and the stragglers were drifting home. Few were left to hear the final selection, 'Jade Visions'. It was the second LaFaro composition that day and was played twice in succession, first as a light cocktail, the 9 / 8 pulse floating, the touch delicate; then slower, digging deeper, a more velvet claret."

This is a wonderful book.

Porter, Lewis. John Coltrane: His Life and Music. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999 paperbound reprint; first hardbound edition 1998.

At p. 104, LaFaro discussed in the context of Ornette Coleman's approach to musical structure and John Coltrane's interest in Coleman's 'free' approach to jazz improvisation:

". . . Coleman had not rejected musical structure, contrary to the claims of his critics. He simply preferred to create a logical structure during his improvisation instead of relying on the given structure of a chord sequence and chorus length. And in fact, most of the time he swung over a walking bass. Coleman's accompanists followed him as they saw fit. The bassist -- usually Charlie Haden, but also Scott LaFaro and Jimmy Garrison -- provided a complementary melodic line but didn't always match Coleman's harmonic directions, so that at times there could be two tonalities suggested at once."

Chapter 15 "So Much More To Do", in which the above quotation appears, presents Coltrane's enthusiasm for the music of Ornette Coleman, even recording (June and July 1960) three of Ornette's tunes. As Porter says, "It is revealing that, perhaps feeling he was not yet ready for free improvisation, Coltrane chose for his session some of Coleman's earliest compositions that do have prearranged chord progressions." (p. 204)

LaFaro, according to the recollection of Los Angeles resident and jazz enthusiast David Berzinski, along with Roy Haynes sat in for Steve Davis and Elvin Jones respectively, played with John Coltrane in April 1961 at Lo's Zebra Lounge. Porter's "Chronology" (pp. 338-377) places Coltrane there "[p]robably May 9-14. Los Angeles. Zebra Lounge (Coda, June 14)" (p. 364). LaFaro and Haynes (and Steve Kuhn) were playing with the new Stan Getz quartet at that time in 1961.

Pleasants, Henry. Serious Music And All That Jazz: An Adventure in Music Criticism. New York: 1971 reprint, a Fireside Book; Simon and Shuster, 1969.

At p. 130, LaFaro is listed among others in an astounding paragraph:

“The consequences of the jazz musicians hazardous and precarious existence may be read in the appalling roll of premature deaths: Mildred Bailey, Shorty Baker, Bix Beiderbecke, Buddy Berrigan, Clifford Brown, Charlie Christian, Nat King Cole, John Coltrane, Tadd Dameron, Eric Dolphy, the Dorsey Brothers, Ziggy Elman, Herschel Evans, Irving Fazola, John Graas, Jimmy Harrison, Stan Hasselgard, Billie Holiday, Bobby Jaspar, Billy Kyle, Tommy Lanier, Scott LaFaro, Booker Little, Jimmie Lunceford, Wes Montgomery, Fats Navarro, Charlie Parker, Oscar Pettiford, Bud Powell, Otis Redding, Django Reinhardt, Art Tatum, Frank Teschemacher, Dave Tough, Fats Waller, Little Walter, Dinah Washington, Chick Webb, Lester Young, and so on and on and on.”