| Our Political Beginnings | The Coming of Indepedence | The Critical Period | Creating the Constitution | Ratifying the Constitution |

Overview

The First and Second Continental Congresses rested on no legal base. They were called in haste to meet an emergency, and they were intended to be temporary. Something more regular and permanent was clearly needed. In this section, you will look at the first attempt to establish a lasting government for the new nation.

The Articles of Confederation

Richard Henry Lee's resolution leading to the Declaration of Independence also called on the Second Continental to Propose "a plan of confederation" to the States. Off and on, for 17 months, Congress considered the problem of uniting the former colonies. Finally, on November 15, 1777, the Articles of Confederation were approved. The Articles of Confederation established "a firm league of friendship" among the States. Each State kept "its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction, and right... not... expressly delegated to the Untied States, in Congress assembled." The States came together "for their common defense, the security of their Liberties, and their mutual and general welfare..." The Articles did not go into effect immediately, however. The ratification, or formal approval, of each of the 13 States was needed first. Eleven States agreed to the document within a year. Delaware added its approval in February 1779. But Maryland did not ratify until March 1, 1781, and the Second Continental Congress declared the Articles effective on that date.

Governmental Structure

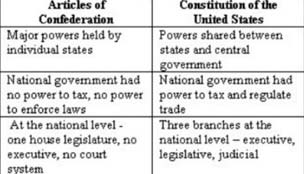

The government set up by the Articles was simple indeed. A Congress was the sole body created. It was unicameral, made up of delegates chosen yearly by States in whatever way their legislatures might direct. Each State had one vote in Congress, whatever its population or wealth. The Articles established no executive or juducial branch. These functions were to be handled by committees of the Congress. Each year the Congress would choose one of its members as its president. That person would be its presiding officer, but not the president of the Untied States. Civil officers such as postmasters were to be appointed by the Congress.

Powers of Congress

Several important powers were given to the Congress. It could make war and peace; send and receive ambassadors; make treaties; borrow money; set up a money system; establish post offices; build a navy; raise an army by asking the States for troops; fix uniform standards of weights and measures; and settle disputes among the States.

State Obligations

By agreeing to the Articles, the States pledged to obey the Articles and acts of the Congress. They would provide the funds and troops requested by the Congress; treat citizens of other States fairly and equally with their own; and give full faith and credit to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other State. In addition, the States agreed to surrender fugitives from justice to one another; submit their disputes to Congress for settlement; and allow open travel and trade between and among the States. Beyond these few obligations, the States retained those powers not explicitly given to the Congress. They, not the Congress, were primarily responsible for protecting life and property. States were also accountable for promoting the general welfare of the people.

Weaknesses

The powers of the Congress appear, at first glance, to have been considerable. Several important powers were missing, however. Their omission, together with other weaknesses, soon proved the Articles inadequate to the needs of the time. The Congress did not have the power to tax. It could raise money only by borrowing and by asking the States for funds. Borrowing was, at best, a poor source. The Second Continental Congress had borrowed heavily to support the costs of fighting the Revolution, and many of those debts had not been paid. And, while the Articles remained in force, not one State came close to meeting the financial requests made by the Congress. Nor did the Congress have the power to regulate trade between the States. This lack of a central mechanism to regulate the young nation's commerce was one of the major factors that led to the adoption of the Constitution. The COngress was further limited by a lack of power to make the States obey the Articles of Confederation or the laws it made. Congress could exercise the powers it did have only with the consent of 9 of the 13 State delegations. Finally, the Articles themselves could be changed only with the consent of all 13 of the State legislatures. This procedure proved an impossible task; not one amendment was ever added to the Articles of Confederation.

The Critical Period, the 1780s

The long Revolutionary War finally ended on October 19, 1781. America's victory was confirmed by the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. Peace, however, brought the new nation's economic and political problems into sharp focus. Problems, caused by weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, soon surfaced. With a central government unable to act, the States bickered among themselves and grew increasingly jealous and suspicious of one another. They often refused to support the new central government, financially and in almost every other way. Several of them made agreements of the Congress, even thought that was forbidden by the Articles. Most even organized their own military forces. George Washington complained, "We are one nation today and 13 tomorrow. Who will treat with us on such terms?" The States taxed one another's goods and even banned some trade. They printed their own money, often with little backing. Economic chaos spread throughout the colonies as prices soared and sound credit vanished. Debts, public and private, went unpaid. Violence broke out in a number of places as a result of the economic chaos. The most spectacular of these events played out in western Massachusetts in a series of incidents that came to be known as Shays' Rebellion. As economic conditions worsened, property holders, many of them small farmers, began to lose their land and possessions for lack of payment on taxes and other debts. In the fall of 1786, Daniel Shays, who had served as an officer in the War for Independence, led an armed uprising that forced several State judges to close their courts. Early the next year, Shays mounted an unsuccessful attack on the federal arsenal at Springfield. State forces finally moved to quiet the rebellion and Shays fled to Vermont. In response to the violence, the Massachusetts legislature eventually passed laws to ease the burden of debtors.

A Need for Stronger Government

The Articles had created a government unable to deal with the nation's troubles. Inevitably, demand grew for a stronger, more effective national government. Those who were most threatened by economic and political istability - large property owners, merchants, traders, and other creditors - soon took the lead in efforts to that end. The movement for change began to take concrete form in 1785.

Our Political Beginnings | The Coming of Independence | The Critical Period | Creating the Constitution | Ratifying the Constitution