| Our Political Beginnings | The Coming of Indepedence | The Critical Period | Creating the Constitution | Ratifying the Constitution |

Overview

The American system of government did not suddenly spring into being with the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Nor was it suddenly created by the Framers of the Constitution in 1787. The beginnings of what was to become the United States can be found in the mid-sixteenth century when explorers, traders, and settlers first made their way to North America. The French, Dutch, Spanish, Swedes, and others contributed to the European domination of this continent - and to the domination of those Native Americans who were here for centuries before the first Europeans arrived. It was the English, however, who came in the largest numbers. And it was the English who soon controlled the 13 colonies that stretched for some 1,300 miles along the Atlantic.

Basic Concepts of Government

The earliest English settlers brought with them knowledge of a political system - established laws, customs, practices, and institutions - that had been developing of centuries. The political system they knew was that of England, of course. But some aspects of that structure had come to England from other times and places. For example, the concept of the rule of law that influenced English political ideas had roots in the early river civilizations of Africa and Asia. More directly, the ancient Romans who occupied much of England from A.D. 43 to 410 left behind a legacy of law, religion, and custom to the people. From this rich political history, the English colonists brought to North America three ideas that were to loom large in the shaping of government in the United States.

Ordered Government

Those first English colonists saw the need for an orderly regulation of their relationships with one another - that is, for government. They created local governments, based on those they had known in England. Many of the offices and units of government they established are still with us today: the offices of sheriff, coroner, assessor, and justice of the peace, the grand jury, counties, township, and several others.

Limited Government

The colonists also brought with them the idea that government is restricted in what it may do, and each individual has certain rights that government cannot take away. This concept is called limited government, and it was deeply rooted in the English belief and practices by the time the first English ships reached the Americas.

Representative Government

The early English settlers also carried another important concept to America: representative government. This idea that government should serve the will of the people had also been developing in England for centuries. With it had coming a growing insistence that the people should have a voice in deciding what government should and should not do. As with the concept of limited government , this notion of "government of, by, snd for the people" found fertile soil in America, and it flourished here.

Landmark English Documents

These basic notions of ordered government, of limited government, and of representative government can be traced to serveral landmark documents in English history.

The Magna Carta

A group of determined barons forced King John to sign the Magna Carta - the Great Charter - at Runnymede in 1215. Weary of John's military campaigns and heavy taxes, the barons who developed the Magna Carta were seeking protection against heavy-handed and arbitrary acts by the king. The Magna Carta included such fundamental rights as trial by jury and due process of law - protection against the arbitary taking of life, liberty, or property. These protections against the absolute power of the king were originally intended only for the privileged classes. Over time, they became the rights of all English people and were incorporated into other documents. The Magna Carta established the principle that the power of the monarchy was not absolute.

The Petition of Right

The Magna Carta was respected by some monarchs and ignored by others for 400 years. During this time, England's Parliament, a representative body with the power to make laws, slowly grew in influence. In 1628, when Charles I asked Parliament for more money in taxes, Parliament refused until he signed the Petition of Right. The Petiton of Right limited the king's power in several ways. Most importantly, the document demanded that the king no longer imprison or otherwise punish any person but by the lawful judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land. It also insisted that the king not impose martial law (rule by military) in time of peace, or require homeowners to shelter the king's troops without their consent. In addition, the Petition stated that no man should be, "compelled to make or yield any gift, loan, benevolence, tax, or such like charge, without common consent by act of parliament." The Petition challenged the idea of the divine right of kings, declaring that even a monarch must obey the law of the land.

The Bill of Rights

In 1688, after years of revolt and turmoil, Parliament offered the crown to William and Mary of Orange. The events surrounding their ascent to the throne are known in English history as the Glorious Revolution. To prevent abuse of power by William and Mary and all future monarchs, Paliament, in 1689, drew up a list of provisions to which William and Mary had to agree. This document, the English Bill of RIghts, prohibited a standing army in peacetime, except with the consent of Parliment, and required that all parliamentary elections be free. In addition, the document declared "that the pretended power of suspending the laws, or the execution of laws, by regal authority, without cosent of Parliament is illegal. . . that levying money for or to the use of the Crown. . . without grant of Parliament. . . is illegal. . . that it is the right of the subjects to petition the king. . . and that prosecutions for such petitioning are illegal. . ." The English Bill of Rights also included such guarantees as the right to a fair trial, and freedom from excessive bail and from cruel and unusual punishment. Our nation has built on, changed, and added to those ideas and institutions that settlers brought here from England. Still, much in American government and politics today is based on these early English ideas.

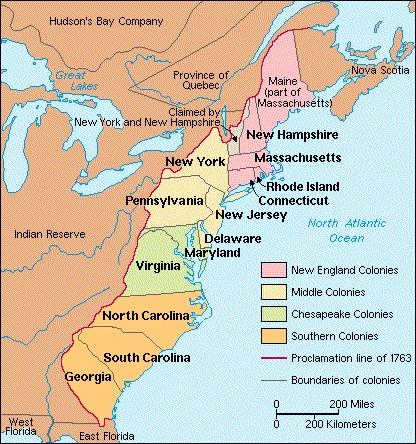

The English Colonies

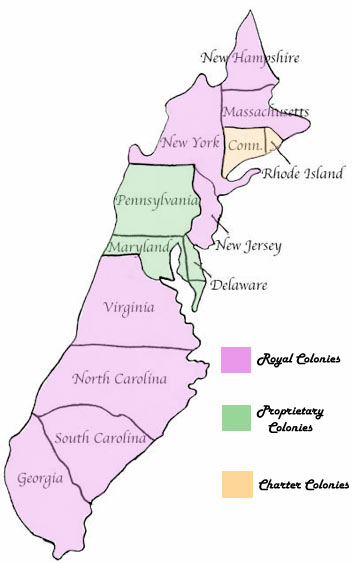

Each of the 13 colonies was established on the basis of a charter, a written grant of authority from the king. Over time, these instruments of government led to the development of three different kinds of colonies: royal, proprietary, and charter.

Royal Colonies

The royal colonies were subject to the direct control of the Crown. On the eve of the American Revolution in 1775, there were eight: New Hampshire, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. The Virginia colony did not enjoy the quick success its sponsers had to promised. So, in 1624, the king revoked the London Company's charter, and Virginia became the first royal colony. Later, as the orginal charters of other colonies were canceled or withdrawn for a variety of reasons, they became royal colonies. A pattern of government gradually emerged for each of the royal colonies.The king named a governer to serve as the colony's chief executive. A council, also named by the king, served as an advisory body to the royal governor. In time, the governer's council became the upper house of the colonial legislature. It also became the highest court in the colony. The lower house of a bicameral legislature was elected by those property owners qualified to vote. It owed much of its influence to the fact that it shared with the governor and his council the power of the purse - that is, the power to tax and spend. The governor, advised by the council, appointed the judges for the colony's courts. The laws passed by the legislature had to be approved by the governor and the Crown. Royal governors often ruled with a stern hand, following instructions from London. Much of the resentment that finally flared into revolution was fanned by their actions.

The Proprietary Colonies

By 1775, there were three proprietary colonies: Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. These colonies were organized by the proprietor, a person to whom the king had made grant of land. By charter, that land could be settled and governed much as the proprietor chose. In 1632 the king had granted Maryland to Lord Baltimore and in 1681, Pennsylvania to William Penn. In 1682 Penn also acquired Delaware. The governments of these three colonies were much like those in the royal colonies. The governor, however, was appointed by the proprietor. In Maryland and Delaware, the legislatures were bicameral. In Pennsylvania, the legislature was a unicameral body. There, the governor's council did not act as one house of the legislature. As in the royal colonies, appeals from the decisions of the proprietary colonies could be carried to the king in London.

The Charter Colonies

Connecticut and Rhode ISland were charter colonies. They were based on charaters granted in 1662 and 1663, respectively, to the colonists themselves. They were largely self-governing. The governors of Connecticut and Rhode Island were elected each year by the white, male property owners in each colony. Although the king's approval was required before the governor could take office, it was not often asked. Laws made by their bicameral legislatures were not subject to the governor's veto nor was the Crown's approval needed. Judges in charter colonies were appointed by the legislature, but appeals could be taken from the colonial courts to the king. The Connecticut and the Rhode Island charters were so liberal for their time that, with independence, they kept with only minor changes as State constitutions - until 1818 and 1843, respectively. In fact, many historians say that Britain allowed the other colonies the same freedoms and self-government, the Revolution might never have occurred.

Principles of American Democracy

12.1 Students explain the fundamental principles and moral values of American democracy as expressed in the U.S. Constitution and other essential documents of American democracy.

- Analyze the influence of ancient Greek, Roman, English, and leading European political thinkers such as John Locke, Charles-Louis Montesquieu, Niccolò Machiavelli, and William Blackstone on the development of American government.

Our Political Beginnings | The Coming of Independence | The Critical Period | Creating the Constitution | Ratifying the Constitution