By S. Amjad Hussain

Jeffers wrote an article with the above title about Dr. John H Watson. The venerable Watson of Sherlock Holmes fame was an army surgeon in the second Anglo-Afghan War. He sustained a bullet injury during one of the campaigns in 1880, was rescued and brought to Peshawar where he remained for a while before his return to London.

"How are you?... You have been to Afghanistan, I perceive." are the first words spoken by Sherlock Holmes to Dr. Watson (Doyle, "A Study in Scarlet" [1881]). "How on earth did you know that?" Watson asks. This was the first of many displays of Holmes's deductive powers to the always admiring Watson

Surgeon-writer S. Amjad Hussain of Toledo, Ohio was born in Peshawar, near the Afghanistan border, along the Northwest Frontier of Pakistan, and in this article contributed to the Sarhad Conservation Network, he suggests a somewhat different interpretation.

second Afghan War in 1880 at Maiwand, a town about 50 miles from the southern Afghan city of Kandahar. The British were roundly defeated in that battle, as they were in all their engagements with the Afghans, and retreated to the British side of the still unmarked border between Afghanistan and British India.

We are not told how Watson made it to Peshawar after his faithful

companion Murray picked him up. They could have taken the southern route to Peshawar or could have traveled north within Afghanistan to reach the Khyber Pass in the Suleman Koh (mountain) ranges and then made his way through the Afridi country down to the frontier town of Peshawar. Since the Khyber route was well traveled and relatively safe, the British troops would have used that route.

Though they have been in India for over a century, the British came to

the Northwest Frontier in 1849 under the command of Sir Walter Gilbert. They laid the foundation of a new garrison town - 'cantonment' in the subcontinent lexicon - in the marshland west of the old walled city and settled down to a 100-year uneasy rule over the Frontier.

In 1895 the British took advantage of a weak Afghan king, Abdur Rahman Khan, to force border demarcation between Afghanistan and British India. The new border known as the Durand Line, was drawn west of the Khyber Pass slicing through Suleman and Hindu Kush Mountains and tribal homelands instead of the age old geographic line following the Indus River 80-miles to the east. This brought Peshawar valley, the area between the Indus River and the Khyber Mountains, in British control. After the partition of the Indian Subcontinent into India and Pakistan, Afghanistan demanded the return of the area and for the next 32-years the issue remained a bone of contention between the two countries. The Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in 1979 changed the equation in favor of Pakistan. In 1880 when Watson visited Peshawar, the city was still claimed by Afghanistan.

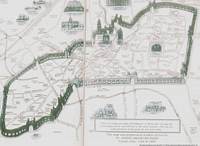

Watson is believed to have been brought to the Balahisar Fort located

just outside the city (1-see map). The imposing fort was originally built by the Mogul emperor Babur in 1530 and subsequently rebuilt by Hari Singh Nalwa, the trusted general of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1830’s. The British reinforced it with brick and made it their head quarters. ‘Here, I rallied’, says Watson about his recuperation at Peshawar. If he were indeed at the fort he would have a fantastic panoramic view of the city and the surrounding countryside.

Mr. Jeffers in his article says that Watson, knowing his adventurous spirit, would have ventured in the old city to ‘explore the fascinating settlement outside’.

He further says that Watson would have entered the city through Gunj

Gate, one of the 18 gates that sheltered the walled city from outside. If Watson were to go to the city from the fort he would have gone into the city through Asamai gate (2), the nearest gate to the fort and not through the Gunj gate (3) which happens to be on the opposite (eastern) part of the city.

After entering the city, Watson would have passed by the imposing Mahabat Khan Mosque, built a century and half earlier by the Mogul governor of Peshawar of the same name. He would have found that the top cupolas of the mosque minarets had been removed leaving the top of the minarets flat. When the Sikhs captured Peshawar in 1826 they destroyed, as was their custom, the top of the minarets.

He would have also learnt about the cruelty of the Sikh governor of

Peshawar, an Italian mercenary by name of Avitabile, who ruled the area with an iron fist. Every morning before breakfast he would have a few of the Muslim 'true believers’ hurtled from atop the minaret to ‘teach the unruly people a lesson’.

His ruthless cruelty has passed on into the local folklore where even

today mothers in the inner city of Peshawar scare their naughty children from the wrath of Abu Tabela, local corruption of Avitabile.

A short uphill walk from the City Square, later called Chowk Yaadgaar or the Memorial Square, he would have come to the hill top citadel of

Gorkhatree (4).

The Moguls built this ancient structure as a caravan sarai but in the

beginning of the Christian era it housed the begging bowl of Lord Buddha.

Avitabile lived in this citadel and according to another local folklore kept an eye on the citizens from his hill top residence with the help of a powerful telescope.

The era records do not show the presence of a full-scale hospital within

the fort. But there was a British run hospital on Egerton Road (5) within

the walled city that catered to the needs of the local population and

possibly the needs of the British soldiers as well. It is quite possible that Watson recuperated at the Egerton Road facility. This would have given him the opportunity to leave the hospital in the company of Murray and enjoy the sight and smells of the city. He probably drank from the famous cold water well of Shahbaz (Shabaz-da-Khoo) within sight of the hospital on Egerton Road.

Before refrigeration came on the scene in the early fifties, the city dwellers depended on ice cold water drawn from the deep wells in the suffocating summers months.

A short westwardly walk from the hospital would have brought him to the fabled bazaar of Storytellers or the Kissa Khani Bazaar (6). Lowell Thomas the famous American traveler called this bazaar the Piccadilly of Central Asia. In its tea shops and caravan sarais travelers from all parts of the world leaned against the carpet cushions and traded stories over the cups of green tea.

Watson would have certainly enjoyed the steaming hot dishes of chapli kabob, resin pilaf and fried mahsher fish from the Indus.

Close to the bazaar of Story Tellers on the bank of the tiny Bara River

stood a magnificent Peepal tree that had stood guard for 2000-years. In the days of King Kanishka in the first century AD Buddhist pilgrims came from all over the eastern world to pray at the site and visit the begging bowl on the hilltop.

Little did he know that within 100-years of his visit to Peshawar the tree

would be mercilessly cut down by the city fathers without any regards for its history.

I also think that Watson would have wandered the city disguised as a

fair-skinned traveler from the Caucuses rather than an Englishman. To do otherwise would have meant courting personal injury and even death.

Though Peshawar was at the time, unlike the turbulent frontier, in firm control of the British, the colonial masters never mixed with the local population and never visited the city without an escort. A solitary Englishman was liable to have a Khyber knife driven through his heart if found roaming the labyrinthine streets and alleys of the old city.

In the past century Peshawar has changed in many ways. Overpopulation, influx of two million Afghan refugees, economic hardships, uncontrolled urban sprawl and the resultant urban decay has changed the face of this historic frontier outpost. But more than any city in the subcontinent Peshawar remains an exciting place where while taking a walk through its narrow streets and alleys, one sees the past merge seamlessly with the present and hear the echoes of a drama that has been unfolding here for over three thousand years.

One could imagine myriad scenarios for Watson’s visit to Peshawar. It is of course pure conjecture. But then conjecture is not a new concept for Holmes or the Sherlockians. In The Empty House Sherlock Holmes says: ‘Ah! My dear Watson, there we come into the realm of conjecture where the most logical mind may be at fault. Each may form his own hypothesis upon the present evidence, and yours is as likely to be correct as mine."

S. Amjad Hussain

The author S. Amjad Hussain is a columnist on the op-ed pages of the Daily Toledo Blade and a Clinical Professor of Surgery at the Medical College of Ohio. He can be reached at:

< [email protected] >