Ours was one of the rare families who lived inside the walled city, otherwise Pathan families usually lived in the suburbs or in the tribal areas. Now Karimpura and Ghanta Ghar seem to be a Pathan country. Peshawaris have moved to the relatively new housing schemes like Hayatabad, University Town and Gulbahar - no more new - selling their old abodes to the keen Pathans or to those who preferred to stay behind. I could not muster enough courage to visit my house where I spent my early years. The house had been demolished by the new owners and my parents, who made it a loving home, were not there. My father is somewhere in the sands of Bahrain and my mother is asleep close to her sister in a graveyard.

The narrow lanes of the old city have become more cramped because many of the old houses have been replaced by shopping plazas. You would not find a bhatyaran cooking for the wayfarers in the late evenings, which was a common sight in the days of yore. Nor would you see seekh kebab and tikka restaurants at the ground floor of houses in the lanes where water-men used to have their lunch. The music bands with their trumpets could be seen near the balconies of houses in the vicinity of Ghanta Ghar, waiting for a call to play at any ba’arat.

The florist who sat next to the Ghanta Ghar selling garlands of flowers for all occasions, is now selling garlands of currency notes. For the residents of Peshawar, it has been a centuries old tradition to attend happy occasions as well as sad incidents with flowers. They are not presented as bouquets, but are put in a string or a garland for the neck. If you were visiting an ill person, it was a must in the old days that you did that with a garland, even if it was only a single string. The road used to smell of roses in the spring as the vendors used to sell roses and rose petals in large baskets on the roadside. Heaps of spinach and other green vegetable have replaced the flowers, and women throng the vendors to get fresh supplies.

Centuries old public bath for women has also gone. It was a place frequented by Qazalbash women and my mother, who came from Afghanistan, also used to go there. I accompanied my mother to the bath a few times, but never dared to step inside. The public bath for women may have shifted to some other posh locality as more affluent Afghans are now settled in those areas.

Close to the Ghanta Ghar and in front of the Vegetable Market, there is a public toilet. There is another one in Saddar, close to the car parking in front of Koochi Bazaar (Kapra market). The municipality has imposed an entry fee of rupees two. It is clean with running water and flush system. There is a guard stationed outside, so that no man enters the toilet when a woman is using it.

Karimpura, where renowned artist Ismail Gulgee was born, has absolutely lost its old character. It is now a cloth market. Old houses are now replaced by shops. Nobody ever thought of, or suggested, declaring Gulgee’s birthplace as a national heritage. The only place in the old city that was declared as part of the national heritage was Mohalla Sethian with its big beautiful houses. Sethian Street is very wide and less winding as compared to other streets of the old city. The houses were built on the style of havelis with large entrance doors.

Sethi Karim Baksh’s house was built in 1900 its woodwork and walls decorated with frescoes looking like something from the other world. The Sethis had flourishing business ties with Shanghai, Kabul, Bombay, Amritsar, Karachi and Central Asian states. The socialist revolution of 1917 reversed their fortunes, and their millions in Russian currency became worthless overnight. They built spacious havelis for their families and participated in a lot of public welfare activities. Between Gorekhatri and Ghanta Ghar, there used to be a huge well of cold water known as Sethi Karim Baksh Well. It had many spools for pulling up water. In the scorching heat of Peshawar, many a time, I also drank the sweet and cold water from the well.

With the passage of time, their families expanded. Some of them moved to other cities and most of them shifted to new housing societies. Maintenance of these huge havelis had become very expensive for them. Though some of the old families are still living in the havelis, they use just a portion of it and keep the rest closed. Mr. Wasil Sethi was kind enough to provide me information about their family and photographs of part of the houses. I have been in and out of these havelis, as my classmates used to live in them. I even had the pleasure of having lunch in there. The ladies of the Sethi family used to make really delicious Mughlai dishes.

When residents from old city lanes moved over to the new houses, they took away their mentality, etiquette and mannerism. Not only that, they took the antiques from their old dwellings with them. One usually does find parts of antique chandeliers hanging from the roofs of modern houses. The most common sight is a carved wooden door with an old steel knob and chain placed in a new concrete wall. Affluent settlers from Afghanistan also added spice to the colorful culture of Peshawar. Afghani tikka and pillao restaurants have become an old story. One can now spot shops with white bridal gown (patronized by Afghan women) and accessories like decorative baskets for carrying wedding rings. One can see locals bargaining for these baskets. Young Afghan girls are adopting the ways of Peshawari girls, and vice versa. One can hear duets in public buses in Pushto and Persian. Inter-marriages are also taking place between Afghan and Peshawari families and now they are so integrated in Peshawar that only those would want to go back to Afghanistan who are housed in refugee camps like Jalozai.

Begum Kulsoom Saifullah, an eminent figure of Peshawar and mother of Saifullah brothers, narrated a similar story. She was talking to a group of people (It was after the Mujahideen had ousted the Russians from Afghanistan) and said that one day our Afghan brethren would go back to their land gracefully but a bearded man came over and said:

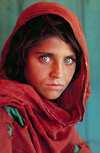

"The color of your eyes and mine is the same. We two have the same complexion and speak the same language. It means your forefathers must also have come from Afghanistan. Why do you think that we would want go back?"

Shamim Akhtar