THE HANDMAID'S TALE

Trivia ↓ Questions & Ideas ↓ Sources ↓ Links ↓

The Handmaid's Tale, first published in 1985, is probably Atwood's most famous work. Set in the not-too-distant future in the fictional Republic of Gilead (formerly the United States), it tells the story of the Handmaid Offred. As a Handmaid, Offred's only value to Gilead's ultra-conservative society is her potential fertility. She is no more than an indentured slave in the household of a bureaucratic Commander and his sterile Wife. Although she still remembers her former life of freedom, she must now endure a society in which women are not allowed to read, think, or love.

The book can be read on many levels-- as satire, as a cautionary tale, as a work of feminism or science fiction. Ultimately, it is all of these and more. It has been adapted for stage and screen, is taught in universities around the world, and has been translated into dozens of languages.

Trivia

![]() The original title was Offred.

The original title was Offred.

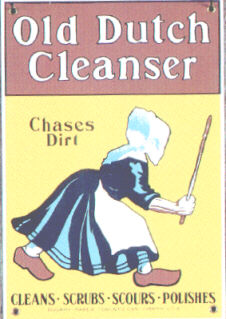

![]() Atwood�s inspiration for the handmaids� uniforms was apparently the label from Old Dutch Cleanser cans, which she remembered from childhood as particularly unsettling, since their faces were hidden (Sullivan, 327):

Atwood�s inspiration for the handmaids� uniforms was apparently the label from Old Dutch Cleanser cans, which she remembered from childhood as particularly unsettling, since their faces were hidden (Sullivan, 327):

![]() The word "handmaid" comes straight from the Genesis story used as the basis of Gilead's procreative program:

The word "handmaid" comes straight from the Genesis story used as the basis of Gilead's procreative program:

And when Rachel saw that she bare Jacob no children, Rachel envied her sister; and said unto Jacob, Give me children, or else I die. And Jacob's anger was kindled against Rachel; and he said, Am I in God's stead, who hath withheld from thee the fruit of the womb? And she said, Behold my maid Bilhah, go in unto her; and she shall bear upon my knees, that I may also have children by her. And she gave him Bilhah her handmaid to wife: and Jacob went in unto her. And Bilhah conceived, and bare Jacob a son. And Rachel said, God hath judged me, and hath also heard my voice, and hath given me a son� (Genesis 30:1-6)

![]() The dedicatees of The Handmaid's Tale are Mary Webster and Perry Miller. Webster was an ancestor of Atwood's -- a "witch" who survived a sentence of death by hanging in 17th century Connecticut. Miller was a professor whom Atwood met during her Harvard years. From him she learned about the religious mindset of early New England settlers, whose history influenced many aspects of the young republic of Gilead.

The dedicatees of The Handmaid's Tale are Mary Webster and Perry Miller. Webster was an ancestor of Atwood's -- a "witch" who survived a sentence of death by hanging in 17th century Connecticut. Miller was a professor whom Atwood met during her Harvard years. From him she learned about the religious mindset of early New England settlers, whose history influenced many aspects of the young republic of Gilead.

Questions & Ideas

![]() In her article on nature and nurture in The Handmaid's Tale, Roberta Rubenstein suggests that Atwood expands upon her perennial themes of victimization and survival by "inverting" images of nature and nurture. Do you think that her depiction of "female anxieties with fertility, procreation, and maternity" are at odds with her feminist message? (Rubinstein, 101).

In her article on nature and nurture in The Handmaid's Tale, Roberta Rubenstein suggests that Atwood expands upon her perennial themes of victimization and survival by "inverting" images of nature and nurture. Do you think that her depiction of "female anxieties with fertility, procreation, and maternity" are at odds with her feminist message? (Rubinstein, 101).

![]() Arnold Davidson calls the "Historical Notes" epilogue "the most pessimistic part of the book" (120). Why do you think this is?

Arnold Davidson calls the "Historical Notes" epilogue "the most pessimistic part of the book" (120). Why do you think this is?

![]() Atwood says that The Handmaid�s Tale was inspired in part by a trip to Afghanistan, and a subsequent dinnertime conversation about religious fundamentalism. The two questions Atwood wanted to consider were: �If women�s place is in the home, why aren�t they in it, and how do you get them back in? And: if you were going to take over the United States, what slogans would you use?" (Atwood, quoted in Cooke, 276).

Atwood says that The Handmaid�s Tale was inspired in part by a trip to Afghanistan, and a subsequent dinnertime conversation about religious fundamentalism. The two questions Atwood wanted to consider were: �If women�s place is in the home, why aren�t they in it, and how do you get them back in? And: if you were going to take over the United States, what slogans would you use?" (Atwood, quoted in Cooke, 276).

![]() Of Offred Atwood says: �The voice is that of an ordinary, more-or-less cowardly woman (rather than a heroine). Because I suppose I�m more interested in social history than in the biographies of the outstanding� (Atwood, quoted in Cooke, 276). Is Offred cowardly?

Of Offred Atwood says: �The voice is that of an ordinary, more-or-less cowardly woman (rather than a heroine). Because I suppose I�m more interested in social history than in the biographies of the outstanding� (Atwood, quoted in Cooke, 276). Is Offred cowardly?

![]() Erica Joan Dymond uncovers a running thread of pearl- and oyster-related imagery in the text, starting with Aunt Lydia's exhortation to "Think of yourselves as pearls" (145). (Also see chapters 24, 28, and 34.) There are many other instances of perverted images of fertility in the book. What is Atwood's point?

Erica Joan Dymond uncovers a running thread of pearl- and oyster-related imagery in the text, starting with Aunt Lydia's exhortation to "Think of yourselves as pearls" (145). (Also see chapters 24, 28, and 34.) There are many other instances of perverted images of fertility in the book. What is Atwood's point?

Sources

For further reading on The Handmaid's Tale, please see the article and book lists.

- Atwood, Margaret. "If You Can�t Say Something Nice, Don�t Say Anything at All� in Language in her Eye. Ed. Libby Scheier et al. Toronto: Coach House, 1990. 18-19.

- Davidson, Arnold E. "Future Tense: Making History in The Handmaid's Tale." Margaret Atwood: Vision and Forms. Ed. Kathryn VanSpanckeren and Jan Garden Castro. Carbondale & Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1988. 113-121.

- Dymond, Erica Joan. "Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale." Explicator 61 (2003): 181-183. [Available on EBSCOhost]

- Evans, Mark. "Versions of History: The Handmaid's Tale and its Dedicatees." Margaret Atwood: Writing and Subjectivity: New Critical Essays. Ed. Colin Nicholson. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994. 177-188.

- Hengen, Shannon. "Power Revisited: The 1980s' Texts." Margaret Atwood's Power: Mirrors, Reflections and Images in Select Fiction and Poetry. Toronto: Second Story Press, 1993. 87-102.

- Rubenstein, Roberta. "Nature and Nurture in Dystopia." Margaret Atwood: Vision and Forms. Ed. Kathryn VanSpanckeren and Jan Garden Castro. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1988. 101-112.

Links

Professor Paul Brians from Washington State University has prepared a chapter-by-chapter companion to The Handmaid's Tale which features lots of interesting questions to guide reading & analysis by students.

Here is a link to a site about The Handmaid's Tale: The Opera.

IMDb.com's page on the 1990 film adaptation.