Khe Sanh Veterans Association Inc.

Red Clay

Newsletter of the Veterans who

served at Khe Sanh Combat Base,

Hill 950, Hill 881, Hill 861, Hill 861-A, Hill 558

Lang-Vei and Surrounding Area

Issue 47 Fall 2000

Short Rounds

![]()

Home

In This Issue

Notes from Editor & Board Incoming Health

Matters Memoirs

In Memoriam

Email A Sprinkling of Your Poetry

![]()

Articles in this Section

A Letter to Ray Stubbe

First Cavalry Troopers Steal Flag from Khe Sanh

MEMORANDUM for The PRESIDENT

The Rats of Khe Sanh

Dave "Doc" Steinberg

Charles Kelley 2/ 94th Arty The

Original KA-BAR

®

Ira D Wilson No

Small Things Armed and Ready

![]()

Written in 1993

Dear Ray,

A short letter to cover the enclosed writing I am sending you. For a long, long

time, it has been within me, unable to put down in words the images that are its

background. I have talked to "Charlie" quite a bit over the years.

Some of it I know comes from a guilt trip but part of it, too, I feel comes from

what it all represents. It was the end of an era for me, and the beginning of

another age. One in which I would struggle just as hard to sort out all the

confusion and questions. It is awfully easy to say I saw death, or, I

experienced the violence of it. To proclaim that one is a veteran of war. To be

knowledgeable of the whims of battle. But, too often many of us let it end

there. We hide behind the pain and anger of it. Not willing to take that one

anguish filled giant step that will begin the very slow ascent into not just

being veterans of it, but being veterans of what it means to us; our comrades;

our whole way of life. We are scared, and deservedly so, of the process of

transfusion from that old to our new selves. Unresolved conflicts, personal in

nature, litter the domain of our inner beings. To reach them, we must sort

through so much "clutter"--much of it that we wish better left

undisturbed. Disturbing them disturbs us. Causing much mental turmoil in the

process. We are forced to relive much that we thought we had left behind.

Unfortunately, many times it is the down side and not the upside that is

remembered.

The overwhelming nature of war is thus. Even the happy times with a lost comrade, are translated into sadness. His passing seems to have cast a pall of gray over all that is related to him. And yet, it should not be so. This is the clutter, the mayhem, the relegated trash that must be sorted through. The good times were good. The happy times were happy. The laughter genuine and real. A treasure of sharing and bonding. We must not let the loss offset or overburden that. We cannot surrender to war's circumstances the true memories and experiences of it. They are buried; buried deep and buried strong. We have a fear that somehow if we consider what happens good, then we are letting those who did not come back, down. But those of us who came back, we must force ourselves to suffer a little more. Overcome the hurdle, take the initiative to start a new push. Learn and grow from the tears of the heart. No greater pain is there, than the pain of the soul. No greater love is there, than the love from that pain.

The bonds of war are like a marriage--"till death do us part." And many times that is the way of those who do battle. But parting should not mean separation. Physically the loss is there, but in the mind, there is so much new source of inspiration, that separation need never occur. Most of those who I saw in their final stillness, I never knew, nor ever will I. Most were not combatants, but civilians whose presence in a war zone was the only reason that that was their home. Age, sex, religion, meant very little. The NVA and Viet Cong occupy the same niche in my being that Marines do. War's effects bring great equality to all those that suffer. This past weekend I watched a special on the Beirut bombing that caused a cynical smile to cross my being. The act of driving a truck loaded with 8 tons of TNT into the Marine Barracks was continually referred to as a terrorist act. My mind went back to the continual bombing from high altitudes by B-52's in and around Khe Sanh. Perception and so-called patriotism, provide how you perceive each action. To me there is no difference. Whether 241 Marines died, or 8000 Bru, they died needlessly. Victims of indifference on the part of those who could make a difference. And that is a role I see for a lot of us who have survived war. If we look to the real meaning war has left within us, are willing to endure the pain to let others know, then all of us can make some minute difference. Over the course of generations, the minuteness might grow, so that one day it will overwhelm those who have not learned, and refuse to learn, and the world will live in peace.

I should have known better when I sat down just to add a few personal notes to the enclosed writings. The mind is unpredictable, and sometimes just doesn't know when to stop. Thanks for letting me unload on you. I do not mean to cause you any pain by it. The world of thought can be a very lonely world at times, and it helps when there is someone who it can be shared with. Makes the endurance a mite easier.

Talis Kaminskis

![]()

First Cavalry Troopers Steal Flag from Khe Sanh

I remember the first time I landed at Khe Sanh during the siege. I contacted the Tower (actually a man with a radio in a hole in the ground) and received clearance to land and refuel. As we started to refuel the enemy started walking mortars towards us. I started to depart, calling the tower and got the reply, "YES, EVERY TIME ONE OF YOU ASSHOLES FLIES IN HERE, THEY START SHELLING US."

I replied, "You could've said something else, THIS IS MY FIRST TIME HERE."

B Company of the 229th AHB 1st CAV Division (Killer Spade) had been tasked to supply helicopter support to Special Forces (actually SOG) at Khe Sanh. The mission required two lift ships, one to do the mission and the second to rescue the first. Two gun ships would supply close gun cover during the missions. These were usually from D Company/ 229th (Smiling Tigers) but were sometimes from other units. The missions were usually to insert and/or extract six man teams into and out of Laos.

Shortly after the Khe Sanh Combat Base had been vacated, I arrived at the relocated Special Forces camp for a SOG Mission. A Special Forces captain informed me that the scheduled mission was canceled but that the NVA were flying their flag off the main flag pole at the former Khe Sanh Combat Base and then added. "What do you think of that?" Naturally, we would task ourselves with a new, self-appointed mission to "capture the flag." I was happy to be flying this day with a good pilot, Mike LaPierre. He was a new pilot and as he was flying enroute I would roll up the chart and hit him about the head to simulate stress. In the chase ship was another new pilot, Bob Hicks, who later became the unit safety officer. For some reason, we seemed to always have a high turnover rate for these missions.

Our gun team was Two Cobra AII-1G attack helicopters from the Smiling Tigers. As we approached Khe Sanh we could see the NVA flag. The gun ships started firing rockets, then 40 mm grenades hoping to destroy or detonate any booby traps. Unexploded ordnance could be seen lying on the ground. As we came closer, we started to orbit around the flag with our door gunners spraying the area with M-60 and the Cobras spraying miniguns. Just as I was about to nuke my move for the flag, My wing man broke the orbit first and hovered next to the flag. One of his door gunners reached out and wrapping the flag around his arm, pulled the flag from the pole with a sharp tug. I immediately thought of "trip wire." I pulled in full power trying to put some distance between us and the upcoming explosion. No explosion came and we made it back to the Special Forces Camp with our Prize.

I am very proud to have flown into and out of Khe Sanh during the siege and

to have helped in some way the many brave individuals who gave so much in the

service of our country.

I am very proud to have flown into and out of Khe Sanh during the siege and

to have helped in some way the many brave individuals who gave so much in the

service of our country.

Thomas I. Harnisher

US Army, B CO 229th AHB

1st CAV & C Troop 1st CAV

29 West 17th Road

Broad Channel, NY 11693

[email protected]

Photo Caption

(Second from left, CW2 Thomas J. Harnisher (Air Mission Commander); third

from left, CW1 Bob Hicks, pilot of 2nd helicopter; lower right, CW1 Mike

LePierre, pilot of lead helicopter)

![]()

MEMORANDUM for The PRESIDENT

Sunday, 21 January, 1968 6:30 AM

South Vietnam

Enemy contacts in the Khe Sanh area, 58 miles west of Hue, have increased and the intensity of the fighting appears to be increasing. US Marines engaged an enemy force near Hill 881, seven miles northwest of Khe Sanh and Marine reaction forces; moving toward the area of contact, engaged another enemy force. There was intermittent fighting for about four hours. The Marines killed 103 of the enemy while losing one Marine killed and 22 wounded.

In another sector of Khe Sanh, a US Army Special Forces patrol observed 30 to 35 enemy in a stream and called for artillery fire which resulted, in 10 enemy killed.

Yesterday a Popular Force platoon made contact with an estimated 200 enemy employing small arms and automatic weapons fire about 40 miles north-northwest of Hue. The Popular Forces were reinforced by an ARVN battalion and US Marines in amphibious tractors. Friendly casualties were five killed (2 Marines and 3 ARVN) and 28 wounded (17 Marines and 11 ARVN). The enemy lost 123 killed.

In Operation Saratoga, 18 miles north-northwest of Saigon, a US Army battalion received small arms, automatic rifle and rocket fire from an enemy force. Artillery and armed helicopters supported the friendly force and the enemy broke contact. Eight US were killed and 15 wounded. Enemy losses are unknown.

In Operation Mac Arthur, nine miles west of Dak To, two US Army companies made contact with an enemy force using recoilless rifle and mortar fire. Friendly forces were supported by artillery and tactical air strikes. Twenty-one of the enemy were killed and 26 US Army personnel were wounded.

North Vietnam

US Tactical aircraft flew 123 sorties over North Vietnam yesterday. Due to poor weather in the target areas, the strikes of special interest scheduled for last night were cancelled:

One US Air Force F-4C on an armed reconnaissance mission was downed by suspected ground fire approximately 15 miles north-northwest of Dong Ho. No chutes were sighted but search and rescue is in progress.

A US Marine A4E aircraft was downed by ground fire near Khe Sanh while flying close air support. The pilot has been picked up and is reported in good condition.

White House Situation Room

Charles E. Hayden

Briefing Officer

**********

MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT

Monday, January 22, 1968 6:30 AM

South Vietnam

Sharp fighting broke out near both ends of the DMZ over the weekend, with the heaviest action taking place around Khe Sanh.

On Saturday a US Marine rifle company in a defensive position on Hill 861 near Khe Sanh came under attack by an estimated 300-man enemy force. The enemy attack was repulsed, but sporadic enemy fire continued for about 12 hours. Fourteen enemy were killed during this action.

At about the same time the Khe Sanh combat base received a mortar attack. Enemy mortar fire continued for about seven hours. The ammunition dump was hit, but the extent of damage is presently not known. The airstrip was also cratered and one helicopter was destroyed and five others received damage. Repair of the airstrip is underway and at least 2000 feet is serviceable.

Then early yesterday morning the enemy began probing the perimeter wire defenses to the south and west of the Khe Sanh airstrip. A Marine rifle company in a defensive position in the area repulsed the attack, killing 14 of the enemy. Marine losses for these actions were 14 killed and 43 wounded.

US Marine aircraft flew 211 sorties in support of the base, accounting for 104 enemy killed.

We have just received a cable from Gen. Westmoreland giving his assessment of the situation at Khe Sanh and the actions he is taking to meet the enemy threat--cable attached.

On Saturday morning, a South Vietnamese sub sector headquarters seven miles southwest of Khe Sanh came under an enemy ground attack. During the attack 12 ARVN were killed and 25 wounded. The enemy lost 92 killed in this battle.

North Vietnam

US pilots flew 175 sorties over North Vietnam yesterday but poor weather hampered operations. No major targets were struck nor were any aircraft lost.

**********

MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT

Tuesday, January 23, 1968 6:30 AM

South Vietnam

US Marines in the Khe Sanh area continue to receive sporadic artillery, mortar and rocket fire from the enemy as the ground action has diminished. As a result of the fire, five marines were wounded.

Civilians are being evacuated from the village of Khe Sanh: 412 have been air-lifted to Da Nang; 300 to the refugee center at Camp Evans, 16 miles west-northwest of Hue; and 400 to Quang Tri City.

A US Marine battalion near Con Thien received 100 rounds of mortar fire and at the same time one mile north two Marine companies made contact with the enemy. After a brief fight the enemy withdrew leaving 3 killed. Marine casualties were 4 killed and 32 wounded.

A US Army company made contact with an enemy force 25 miles northwest of Saigon. After one hour of fighting the enemy withdrew leaving 12 dead. Two US Soldiers were wounded.

An observation post 10 miles west-northwest of Can Tho was attacked by the enemy using small arms and 82ram mortar fire. At the same time the district town of Phong Phu received 20 rounds of 82mm mortar fire. One ARVN was killed: and nine were wounded.

A US Marine F-4B aircraft was shot down by ground fire near Khe Sanh. Both crew members were recovered in good condition. Also an A-4E was hit by ground fire in the same area and the pilot landed inside the defense perimeter.

North Vietnam

Air activity over North Vietnam yesterday was limited to 148 sorties due to adverse weather. All Rolling Thunder strikes scheduled for last night were cancelled due to poor weather in the target area.

White House Situation Room

James L. Brown

Briefing Officer

![]()

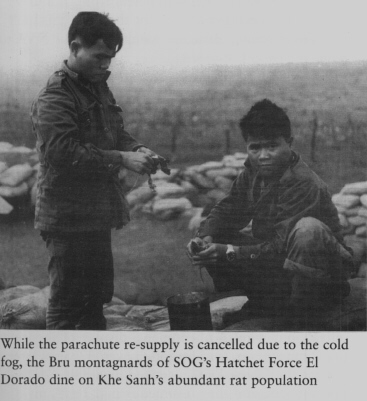

The Rats of Khe

Sanh

Bob Donoghue

As 1968 began to unfold, SOG's Forward Operating Base #3 (FOB-3) located on the Southeastern perimeter of the Khe Sanh Combat Base, began to switch from offensive to defensive operations. As the enemy intensified their indirect fire into the base, more and more time and effort was spent digging and building extensive trench and bunker complexes. Constructed of sandbags, lumber, and aluminum pallets these semi-subterranean complexes soon became home to two kinds of rats. Two legged fatigue-wearing men known as bunker rats and the four-legged hairy rodents known as "The Rats of Khe Sanh."

Khe Sanh's rats lived in the sandbagged bunker structures feeding off the remains of food found inside discarded C ration cans. As nighttime approached they would emerge from their nests to scurry about the area. Anyone trying to get some sleep at one time or another, had one of these critters run across their body. During this time period several people were bitten and had to undergo an extremely painful series of rabies shots.

The tide slowly turned against these rats due to the deteriorating weather conditions and the North Vietnamese Army. The only way to supply the troops with food and ammunition was by parachute drops. After several days of heavy enemy fire and lousy flying weather, the resupply drops tapered off creating a shortage of rations.

Our

indigenous troops, the Bru montagnards, soon devised a plan to supplement their

meager rations. First, they would take a small individual equipment net and

stretch it across the bottom half of a trench. They would then have two other

men start beating on the bunker sandbags with pieces of 2x4's. The rats, being

startled by the banging, would scurry out of the bunker and down the trench line

only to be entangled within the net. A short time later the Bru would be heating

up the water in a #10 can with pieces of C-4 explosive and throwing the captured

rats into the can to cook them. These Khe Sanh rodents provided fine dining at a

time when rations were limited. As the siege progressed it became harder and

harder for the Bru to find these fine tasting rodents.

Our

indigenous troops, the Bru montagnards, soon devised a plan to supplement their

meager rations. First, they would take a small individual equipment net and

stretch it across the bottom half of a trench. They would then have two other

men start beating on the bunker sandbags with pieces of 2x4's. The rats, being

startled by the banging, would scurry out of the bunker and down the trench line

only to be entangled within the net. A short time later the Bru would be heating

up the water in a #10 can with pieces of C-4 explosive and throwing the captured

rats into the can to cook them. These Khe Sanh rodents provided fine dining at a

time when rations were limited. As the siege progressed it became harder and

harder for the Bru to find these fine tasting rodents.

Bob Donoghue

FOB-3

![]()

I enlisted in my junior year of college and joined the U.S. Navy, as my father did in WWII. I was named after his brother 1st Lt. David Steinberg USMCR, assigned to 1/13 as a spotter pilot and based off the USS Saratoga. He was high in the sky spotting for his troops all through Days I & 2 of the Invasion of Iwo Jima.

At the end of Day 2 he was to land on the carrier Saratoga but could not land due to a Kamikaze hit on the deck of the grand 'ole lady. Instead he safely landed on the smaller carrier the USS Bismark Sea. The planes were quickly taken below still fueled and armed, to make way for additional craft off the burning Saratoga.

My Uncle David Steinberg was lost that day as the Bismark Sea took a direct Kamikaze hit mid-ship and sunk with many souls aboard. His remains lost at

sea. His name-sake joined the Navy and ended-up on another Hill, this one called 881S. I survived the entire siege with him looking down from the heavens, which it seemed sometime those of us on that 3,000 foot high hill could just reach out and touch.

And by the way, the brave weapons platoon assigned to 3/26 on Hill 881S, manning the 3 105's and the mortars, were from 1/13, the same unit my Uncle Dave served with so many years before.

Dave "Doc" Steinberg

3rd Plt. India 3/26

Hill 881S Jan-May 1968

![]()

The 2nd Battalion 94th Artillery arrived in Vietnam on 18 October 1966 and was under operational control of the Third Marine Amphibious Group. The 2/94th provided artillery support for the Third Marine Operations from Laos to the South China Sea.

Article from USARV-IO: Camp J.J. Carroll, U.S. Marines are fighting three North Vietnamese Army (NVA) divisions in Quang Tri Province with the aid of the Army's 175mm guns.

This camp, just six miles from the demilitarized zone (DMZ), is the base for the big guns of the 2nd Battalion 94th Artillery. Since the battalion fired the first rounds on Oct. 21, 1966, over 70,000 projectiles have been fired.

The artillery unit is the only Army unit of its type supporting the Marines. All fire missions in the area go through the 3rd Marine Division.

The battalion including Operations Hastings and Prairie and the recent fighting in the DMZ has supported ten Marine operations.

The 175's move around the province so that their 22 mile range can support the Marines, Special Forces, or the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) as they are needed.

Batteries have gone to Con Thien and Gio Linh to fire deeper into North Vietnam.

The big guns have fired across the DMZ since February 22. The targets are given by forward observers in Bird Dog spotter planes flown by Army, Marine, or Air Force pilots and by ground combat forward air controllers assigned to the line companies. Targets have been SAM missile sites, anti-aircraft emplacements, staging and assembly areas of troops, and convoys.

Information Office, US Army Vietnam: "U.S. Army Units in Vietnam Back the Marines with Action. The artillery men of these units along the DMZ don't talk much about how they live in mud filled bunkers and brave the incoming rocket and artillery rounds. They are too busy keeping the enemy busy ducking the shells and small arms fire they throw at him day after day." Actual accounts from Marines on 861A report that an undersized company of the 26th Marines (E/3/26) had not been set up long enough to have their defenses the way they wanted them to be. Early in February 1968, about 3:30 AM, two battalions of NVA regulars contested the Marines for the hill. 175mm supporting fire was called in immediately and continued until 7:00 AM. The 175mm fire support broke up the attacking Battalion and in the words of one of the Marines describing the action stated, "A bunch of pissed off young Marines took care of the rest." In addition to the attacking battalion the Marine FO then turned the fire to the reserve battalion of NVA and all but destroyed them. This combination of devastating 175mm fire support and bravery of the young Marines on 861A preserved the integrity of the hill so important to the defense of Hill 881N and Hill 881S and the Khe Sanh Combat Base. If 861 and 861A had fallen this would have left both 881 hills totally isolated.

A Marine FO from Kilo/3/26: Actual account about 861 and the 175's from Carroll is as follows: On 18 or 19 January 1968 (a day or two before the siege started) my Commanding Officer asked/ordered me to register targets in the ravines and likely approaches around 861. I registered and got target numbers from the 105's, 155's and the 8 inch guns at the base. In addition, I registered some targets on the northern slope of 861 using the 175's at Carroll. To this day, I still remember their call sign Colorado 1/9 and I never did speak directly to them because of the distance 18+ miles. My words and theirs were relayed from the base.

We got all friendlies out of the northern end of the trench line and then I registered the targets. Must have been three or four targets in all. In each case, the final rounds hit less than 50 meters outside our last strand of wire and that's when I cease fired and asked for Target Numbers. Man, those bad boys certainly crunched into the hillside less than 75 yards from my position! I knew the rounds were on the way from the "shot" and "splash" calls, but they still made my teeth rattle.

They fired in support of us again on the night of 20 or 21 January 1968 and I remember 861A using the 2/94th in that early February NVA attack. One

night in mid to late March, the NVA launched rocket after rocket into the base. These 122's were fired from behind 881N and they had to travel almost directly over 861 on their way to the base. I called Colorado 1/9 (through the relay) and gave them the grid squares of the two launch sites behind 881N. My request was that they saturate both grid squares in order to stop this huge, on-going barrage. These grid squares were 1000's of meters from us and would have been max range for the 175's but I felt that just reaching out there would cause the NVA to stop.

Less than three minutes later I was told that the first rounds were on the way. Within seconds, WHAM! WHAM! WHAM! Three or four rounds impacted less than 50 yards outside our wire! Scared the living hell out of all of us in the bunkers and the trench line. We even had a Listening Post right outside the last strands of wire, and those three guys must have shit their pants. Immediate "Check fire" on my part...one more round hit...then all was quiet.

Somehow, the 175mm people thought I had called for my target numbers to be fired, and they responded. Imagine, two and a half months after they were registered, and with no adjustments, and with cold tubes, and from over 18 miles. Those shells hit right outside our wire! A phenomenal display of shooting that I have never, ever forgotten even 32 years later. We got the Check Fire, corrected by a half a dozen grid squares, and they resumed firing. That's my memory of the big guns at Camp Carroll. I just realized that it was 32 years ago today or tomorrow that I registered those guns.

Actual accounts from Marines posted on the East Perimeter of the Khe Sanh Combat Base document a heavy ground attack that was turned with 6 rounds from the 175's on Carroll and Rockpile. Unconfirmed body count was 76. The Marines that were under the attack report smiles on their faces when they saw the 175's heavy destruction of the NVA Regulars that were trying to over run their positions.

Army perimeter defense units at Khe Sanh also report the importance of the 175mm perimeter support when needed expeditiously and were relied on heavily. "We relied heavily on the big 175mm guns at Camp Carroll and the Rockpile to lay in their fire missions at predetermined coordinates and suspected NVA positions."

Actual account of a C Battery 2/94th gunner: "We were always in a rush when we had a fire mission for Khe Sanh. We knew that they were in a very bad spot when they called for us to help them out. That was our job, and we knew that if we were in their place that we would want the most help possible as quick as we could get it, so we always pushed ourselves to see just how fast we could get the rounds out and on the way."

Actual account of a Marine that was around Carroll and Hill 881: "I was an 0311 with 'F' 2/3 from 11/66 to 10/67. I was at Carroll from 11/66 to 3/67. My company would rotate between Carroll and the Bridge down on Highway 9, I don't know if you remember the Bridge? On Feb 28,1967, we were involved in a battle at Cam-Lo. My squad became surrounded and we had to call for fire support from Carroll. I don't know if you were there then or you may have heard that we had to call the 175 rounds on our own position. The guys up at Carroll laid those four rounds right between us and the NVA, which was only a matter of 20 feet or so. Laying on the ground and hearing Carroll launch those 175's knowing they were coming right at us makes me numb to this day. Having those shells rip through the trees and impact right in front of us was the most amazing, scary, bone chilling experience you could imagine. I guess the NVA figured we were crazy because they broke off from us. There is no doubt in my mind that without those well placed rounds my name would be on the Wall. We depended on you guys at Carroll many times to get our butts out of a jam and you were always there."

Excerpt from the S&S Vietnam Bureau: A Marine convoy carrying supplies from Carroll to Khe Sanh was hit three miles from the Rockpile by 200 to 300 NVA Regulars. Many of the 109 communists that were killed were hit by air strikes and 175mm artillery fire.

By reports from supported troops, the NVA hated the big guns at Carroll, Rockpile, Gio Linh, Con Thien and any other places the big guns were assigned in the I Corps area. The big guns could target anti-aircraft firing on U.S. planes, fortifications, and infiltration routes in North Vietnam.

Account from a Marine that was part of the Marine contingent on Carroll during TET: "You may recall a situation where a Marine recon patrol ran into big trouble one late afternoon (March 5, I think). E/2/9 was pulled off the front of Carroll's line to go fetch the dead officer who had been left behind when the patrol was extracted out. But darkness fell before we could lift off the LZ. You guys fired all

night to keep Uncle Ho's Finest away until morning. You guys on the guns were always Johnny-on-the spot when it came to fire support. Thank you very much."I recall a day when my squad escorted a FAO out northwest of Cam Lo. He called in an air strike up in the DMZ and then we just cooled our heels awhile. His radioman carried 2 PRC-25s (wow!) so he could hear both sides of a conversation. Somebody who was awfully excited called in a fire mission. He really rattled it off fast. The FAO said his call sign put him in Khe Sanh. He had to say it all over again because he spoke too fast to get it all. He was asked what his target was and he said, "I got a battalion o' gooks in the open and running." When asked how far away they were, he said, "Fifty meters and closing!" It seemed like only a second before we heard guns open up and the FDC announced, "They're on their way!" Now that's service.

There was one night, though, that y'all really annoyed me. We got the word that Carroll was going to be overrun. So we were pulled back from our front line and placed in a tight perimeter along a dirt "road" directly in front of the 175s. I mean directly in front of the muzzles, about 20 feet!

Every time a gun captain would yell "Stand by!," I'd cover both ears, open my mouth wide, and lay flat on the hard-packed adobe. Then the damned thing would explode, scooting me back 6-8 inches, knocking all the wind out of me. And of course the first gasp only sucked in burnt cordite. Gag a maggot! Even my helmet, set alongside me, would tumble a foot or so. The ground was so hard it broke our Etools trying to scratch its surface. No joy there. I must have dozed and missed a warning order because one cannon went off without my preparations. I think it popped my eardrum, 'cause I got a little blood from it. At that, I just picked up my gear, sat behind the gun, and the NVA and USMC be damned! Of course, nothing happened that night. All plans and intelligence must first be cleared through Hanoi!

Charles Kelley

2nd Bn 94th Arty

![]()

United States Marine Corps

World War II Fighting Knife

"An American Legend"

The U.S.M.C. Fighting Knife is famous in its own right, and has an historical background behind it that is an exciting adventure story and is now an American Legend!

Ask some World War II Marines what kind of knife they depended on during the war and you will get only one answer: a KA-BAR! Back in 1941, after the start of World War II, KA-BAR submitted a Fighting-Utility knife to the United States Marine Corp that was accepted as the standard issue for the Corps.

KA-BAR started supplying these knives and they soon became the prized possession of every fighting Marine. They depended on it for a combat weapon and for such every day tasks as pounding tent stakes, driving nails, opening ration cans or digging foxholes their KA-BAR was constantly at their side.

During World War II, the KA-BAR Fighting Knife earned the greatest respect, not only of the Marines, but also of those who served in the Army, Navy, Coast Guard and Underwater Demolition Teams, who were eventually issued the U.S.M.C./KA-BARS.

Years later, during the Korean, Vietnam and Desert Storm conflicts, many KA-BARS were reactivated into military service, as World War II veterans, remembered how well the knife served them passed their personal KABARS along to their sons.

The dependability and quality of the wartime KABARS weren't the result of just a casual approach to the production of these knives. In addition to the constant quality control procedures of the U.S.M.C. Marine Corps and Navy Supply Depot inspectors, Dan Brown, then President of KA-BAR, and the entire KABAR Company was dedicated to making this knife their contribution to the war effort. As a result of this personal involvement, quality went into the knife that assured its meeting all types of tests without failing. Even tough Marine Corps and Navy tests were supplemented by additional trials, such as driving the knife deep into a 6" x 6" timber and straining the blade back and forth at extreme angles, constantly testing edge retention in cutting through all types of materials and submitting the leather handles to severe atmospheric and corrosion tests to be sure they would hold up under all conditions of cold, heat or jungle rot without loosening or decomposing. As a result, the many thousands of KA-BARS produced during World War II performed so well that the people at KA-BAR were very proud of the reports that came back from all areas of operations and the excellent reputation they had earned. World War II ended and KA-BAR Fighting Knives went out of production until 32 years later when the original

KABAR factory in Olean, New York and some of the craftsmen who worked on the original knife began production again to commemorate the 200th Anniversary of the United States Marine Corps. KABAR wanted to recognize this great milestone in U.S.M.C. history by issuing a "full dress model" of the original KA-BAR---a limited edition that would be most meaningful to the Marines.

Throughout the production of the Commemorative a few KA-BAR senior employees proudly performed the same tasks they worked on during the years 1942 to 1945 when KA-BAR was making its contribution to the war effort. As a result the completed knives were a true "work of art," but retained the look, feel and performance of a battle ready combat knife. KABAR was proud to present Serial No. 1 to the Commandant of the Corps destined to be displayed in the U.S.M.C. Museum at Quantico.

The U.S.M.C. Commemorative was so enthusiastically received that it became obvious that the old KA-BAR Fighting/Utility Knife had retained its notoriety throughout the years. The limited production Commemorative was very quickly taken up by Marines, knife enthusiasts and collectors and KABAR knew that it should now be returned to production, in its standard issue form, with all of the original specifications. Fortunately, they were available because the original blueprints were found in the company archives. So the "fighting KA-BAR" got back into its original gear and today it continues to be a favorite among Marines who adopt them as their own personal option knife and carry them into active service. But it's also a favorite of adventurers, survivalists, outdoor sportsmen and, of course, knife collectors who know that this knife--this "American Legend"--above all, deserves a place in their collection. And so it is, not only in America, but throughout the world.

When the name goes on the blade, it's not just called a "kabar", it is a KA-BAR.

ED. NOTE:

Reprinted from "Ka-Bar Was There," Ka-Bar Knives,

1125 East State St., Olean, New York 14760

![]()

Dear Editor:

My wife and I will not be able to attend, due to how close it is to my recent back surgery, but I want to wish all the best to those who do. Maybe we can catch you at the next one. I would appreciate you sharing some of my thoughts to all the guys who do get to go.

I'm still not allowed to ride in a car or an airplane at all, so travel is out for me right now. I am looking forward to meeting some of those whom we had to evacuate out of Khe Sanh Combat Base. I will be particularly interested in what they've done with their lives since.

You know, when we Air Evac'ed someone, most of the time we only had a very brief contact with them. I usually don't remember an~7one's name or face, but I can remember their wounds, and what I did to treat them. I remember calling in the C-123's and C-130's that it took to get them out, and I remember setting up a system that was unique to Khe Sanh. While I was there, our aircraft could still land, but due to enemy artillery fire, they had to keep taxiing very slowly while they off-loaded supplies. We had propositioned an Aero Med Evac Crew on the aircraft, and as soon as the cargo pallets were off-loaded, this crew would swing down the litter stantions, and stantion straps to be ready to receive the incoming patients. What we would do then is place up to 18 patients on the ground at about the position where the airplane's wing tip would pass over us as he taxied by. Since there were only 4 of us Air Force Medics there, we had to find volunteer Marines to help load the patients. The correct litter carry was to use 4 men, one on each handle. Then they would all start off in step, but for Khe Sanh we had to use only two men per litter because we had to run with them in a dead run. Our timing had to be close to perfect. When the wing tip passed over us, each litter team had to pick their patient up and run directly at the airplane fuselage. By the time we intersected with the path of the airplane, the back end was just passing us. Then we had to make a banking left turn with our litter and jump up on to the tail ramp, as it was still moving. The guy on the front of the litter had the advantage in that he could see the ramp as he jumped up the nearly 18" to get on the ramp. He knew if he missed the step, the guy in back was going to ram that litter right up on him. But the guy in back had the tougher job, because he had to give that litter a real hard shove to help the guy in front get up on the ramp and less than a second later he had to jump up on the ramp himself. If the guy in front made a mistake, and missed the ramp, he would crash down on the ramp and the litter would be driven right up his back. Although we wore flack vests, I still have scars on the back of my neck where the bar underneath the litter hit me in the back of the head. I also have scars on both of my shins where I missed the step up onto the ramp and hit it. That was in our learning stage, but we finally got to where we could hit the ramp at full gallop and run our patient all the way to the front litter tier. We would set him down in the stanchions, while the onboard medics would snap them in place. Then we would make a U-turn and run back out and jump back off onto the ground, before the airplane made the turn at the far end of the ramp. When he made that turn, the loadmaster was closing the door, and as he entered the active runway, he was picking up speed for the takeoff. I am sure that this system of getting patients loaded onto a moving airplane has never been done before or since.

We could usually get about 18 wounded on the aircraft if our timing went well, and we were able to keep up with the pace of the number of wounded we had to move. We weren't too picky though, if an Army or Marine helicopter had room on it, we would send as many patients as possible out on it. The C-123's and C-130's were able to carry so much more that we welcomed them and the opportunity move the bulk of our patient load. At one point while I was there, our bunker took a direct hit, but as I recall we didn't loose anyone. It just scared the hell out of us. But the entire bunker had to be rebuilt. It seemed like we spent as much time refilling sand bags as we did taking care of patients.

By the way, I met Chaplain Stubbe several times when he came over to our bunker and visited our wounded. I have a picture that I think is of him riding on a captured motorcycle. If you see him there, I'd like to know if that was him. The picture is just from the back, but I think I was taking it of him.

Hope you all have a great reunion, and that you'll remember all the ones we didn't get to save. They and their families are the ones that I have the most feelings for, because we didn't have a chance to bring them home. Although most of us didn't get decorated for just doing our job, I believe that every man there was a hero. Even though at the time, nobody wanted to be called one, and maybe most of us still don't, but we did our jobs under very difficult circumstances. We few are a precious band of brothers. I know one thing from all this, my experiences at places like Khe Sanh changed the way I look at life. I treasure every minute of it now. I love being with my two sons and their wives, and especially my grandkids. I love most of all being with my sweet wife, who stood by me all those 13 years I was flying patients around the world. A lot of the guys weren't so lucky. Our divorce rate was astronomical. Most wives couldn't take all the absences. So I'm glad I married an Air Force Nurse, who at least understood what I was doing while I was away. I lost my right lung, and it knocked me off flying status, or I guess I would have still been in AeroMed Evac Units until I retired. Sometimes God just has different plans for you than you do for yourself. Now, I try to go with His flow, and not mine. May God richly bless each and every one of you who attends this reunion.

Semper Fi,

Ira D Wilson

![]()

by Mike Worth

Each year around Mother's Day, I try to visit my Mom in Asheville, North Carolina. Mom, the one who worried as she watched the nightly news, while I was in Vietnam. Wrote faithfully, sent "care" packages, and prayed for my safe return. As she counted the days, she also wrote condolence letters to other parents; those of my boyhood friends and those of too many Echo Company brothers. She said it was just a small thing and the least she could do.

This year I arranged to take a little side trip to Simpsonville, South Carolina to visit with one of my personal heroes, John "Doc" Lancaster, Echo 2/26. Some may remember Commander John Lancaster, USN (Ret) from the dedication at Jefferson Barracks last year--but he is always" Doc" to me. "My" Doc, who when I was wounded on 27 October 1968, ran through a hail of bullets to get to me and patched me up. We spent a day at Laurens High School where Doc Lancaster is now the director of the JROTC program. In his classes, Vietnam became the lesson of the day. The scars from where the bullet went through my arm ( having fortunately missed my head) and Doc's fancy patchwork became the "show and tell" for these interested, pulled together and well mannered young people.

Part of our plan was to also visit the parents and the grave of another Khe Sanh Veteran, Stan Pettit, E 2/26, who survived Khe Sanh, but was Killed in Action later at LZ Margo. Stan was our friend and brother then, remembered still--and John is the Doc who tended to Stan when he was killed by machine gun fire as he walked point on 15 September 1968. And so, we traveled along Liberty Highway to a sleepy rural area between Easton and Liberty, South Carolina to visit Stan's parents, Paul and Colleen Pettit. Stan's brothers, Ray and Eddie and sisters, Paula and Kathy, were at a family wedding rehearsal this day, so maybe next time.

Mrs. Pettit is ill and confined to her bed, but we hoped the flowers brought a touch of cheer and a splash of brightness to her day. Sadly, Mr. Pettit tells us that Mrs. Pettit has never quite gotten over the loss of Stan, their oldest boy.

In a devastating set of circumstances, the Marine Corps failed

to inform the Pettits in a timely manner of the death of their son. The Pettit

family first  learned

of Stan's death when they received a letter of condolence from a Marine in

Stan's squad. Hoping it was a mistake, it was only after Mr. Pettit asked his

Congressman to investigate that they finally received the heartbreaking

confirmation.

learned

of Stan's death when they received a letter of condolence from a Marine in

Stan's squad. Hoping it was a mistake, it was only after Mr. Pettit asked his

Congressman to investigate that they finally received the heartbreaking

confirmation.

Photo Caption

Stan Pettit. 3rd Sqd., 3rd Plt., Echo Co., 2nd Bn 26 Marine Regt, 3rd Marine Div

June-July 1968, Con Thien area near the DMZ

Mr. Pettit, a WWII Marine, who worked in Naval Intelligence and took jungle training in Panama, Central America, is a very warm and most engaging guy, with strong political views and an acute and accurate memory. Paul Pettit is also a loving father whose son fought and died for this country. This father's deep love is evident in the accompanying poem, inspired by a photo of Stan that was sent to the family by a buddy, and was written two days after he buried his eldest son, Stanley.

When we visited Stan's grave, which is in the very center of a small church cemetery near the Pettit home, the roots of the patriotism and sense of duty that was so obvious in Stan, were movingly clear. Rising to nearly 15 feet above the grave with the simple bronze headstone reading Cpl. Stanley R. Pettit, E Co 26th Marines, is a flagpole bearing an American Flag. This powerful symbol of freedom and sacrifice, standing vigil in remembrance of one brave Marine, has flown there for 32 years. For 32 years, Paul Pettit has maintained the grave, reinforced the flagpole, and replaced each fading or tattered flag with a new one. For 32 years, Stan's father has ensured that anyone who visits or drives by this humble churchyard will see this flag--and know that it proudly waves over the resting place of one who gave his life for his country. He says it is just a small thing and the least he can do.

For 32 years this flag tells of duty, honor and sacrifice. May it always fly. May Stanley R. Pettit and so many other brave hearts always be remembered. It is just a small thing and the least we can do.

Author's Note:

The Pettit Family would like to hear from anyone who knew Stan or even has

memories of those times to share. Stan's youngest sister, Kathy Pettit Finley,

will be the Pettit family point of contact and will distribute to all. PH:

864/843-6556, email. TREBKathy2@aol. com Poem used by permission.

Mike Worth

![]()

I stepped on a mine in late February 1968 on Hill 558. My medivac route was from Hill 558 to Dong Ha to DaNang. Each stop included various medical procedures to ensure that I wasn't in pain, the bleeding was controlled and fresh bandages were applied to prevent infection. At Dong Ha, they took off my uniform as added protection from infection.

At DaNang I remember being placed on a stretcher, carried into a building and being set down on a table. I don't remember why. Shortly a rocket attack hit DaNang and they took all the wounded and placed us on the floor. I remember the corpsmen saying that we were probably more used to "incoming" than they were. At DaNang the doctor who examined me took one look at my shattered foot and said, "this one goes afloat." This meant I was headed for the USS Repose, where my foot would be amputated.

For some reason the chopper flight to the Repose didn't take place until nightfall. It was very dark and the flight was crammed with wounded troops. I was placed on the floor and I remember feeling the cold of the steel beneath me, as all I was wearing was a blanket and a huge bandage on my foot. The flight seemed to take forever and once we were over the Gulf of Tonkin, the cold air also entered the cargo (or I should say the meat locker) area. It was so cold I was shivering.

We landed on the Repose on the stern where a landing pad had been built. It took some time to unload the wounded and in my case, since I was targeted for surgery, I was sent immediately to the "preop" (pre-surgery) room. Again all I had on was that blanket. One corpsman took off my bandages and after receiving my approval took pictures of my foot, I guess, for medical textbook purposes. After he was gone I was alone for a while and began to warm up, as I was finally indoors and out of the cold air.

After several minutes a Navy nurse came to see me to prepare me for surgery. She was the first Caucasian woman I had seen in five months and beautiful. I was at least on morphine and probably something stronger by then, but my male senses said this was a gorgeous creature that was about to examine and prepare me for surgery.

In a quick movement she undid the blanket I was wearing and there I was--ARMED AND READY. She took one look at me and said with a smile: "Well, there's definitely nothing wrong with your reactions." I don't remember my response, but I'm sure it was something cute. That night I had the surgery and spent three more days on the Repose recovering before being flown to Japan for additional rest. During those three days on the Repose, I never saw that nurse again as the Navy obviously had separate personnel for separate duties and the nurses who worked pre-op and surgery did not work the recovery wards.

I do remember being out of bed for the first time in a wheel chair and having dinner. After eating I was playing chess or checkers with a "candy striper" who were young teenage girls that were there for comfort purposes. I guess I was too weak to be up so soon, as after about a half hour I promptly threw-up in the candy striper's lap. But, that's another story for another time.

Sure wish I could find that nurse today in my old age. I still have my reactions.

Joe Olszewski

ED NOTE:

Joey, Joey, Joey. Be careful about what you brag on in front of these strange

fellows. Some of 'em are liable to call you on it.

![]()