Khe Sanh Veterans Association Inc.

Red Clay

Newsletter of the Veterans who

served at Khe Sanh Combat Base,

Hill 950, Hill 881, Hill 861, Hill 861-A, Hill 558

Lang-Vei and Surrounding Area

Issue 47 Fall 2000

Memoirs

![]()

Home

In This Issue

Notes from Editor & Board

Incoming Health

Matters Short Rounds

In Memoriam Email

A Sprinkling of Your Poetry

![]()

Articles in This Section

Return to Vietnam

With My Dad Of Madness and

meaning My Buddy Kenny

The Bond

![]()

Returning to Vietnam with my Dad

by Tara Ford

As a young girl growing up, I used to thank God in my prayers for making me a girl. As a child, my perception of reality was that all boys went to war when they grew up. Both of my grandfathers had fought in WWII and my father was a Marine in Vietnam. Although no stories of the wars have been passed down, I instinctively knew that war was Hell. When my grandfather, Gerard "Rocky" Ford, suddenly passed away in 1995 I realized that I didn't know much about him. I didn't know much about the WWII Marine whose picture was on the cover of the NY Times in 1943. I didn't know much about his life experiences, which undoubtedly shaped the man he became. And when he passed, I realized that I didn't know much about my own father's history. My quest to unfurl my father's past began at that moment. My father never spoke about Vietnam. I only knew that he had enlisted in the Marines, received 2 Purple Heart Awards and that a bullet still remained lodged in his leg. I also had no idea the depths of which Vietnam still haunted our society. I didn't know about Agent Orange, B-52s, Napalm, Ho Chi Mirth, POWs, My Lai, TET Offensive, Khe Sanh or even which side the Americans were fighting for. All I knew was that Americans didn't like to talk about the Vietnam War, nor did they like to teach it in school. Unfortunately, all I learned was that Vietnam was something you didn't talk about.

In 1998. I accepted a teaching position in Japan which brought me closer to Vietnam. Vietnam was now my neighbor and not some evil secret. I wanted to visit Vietnam but I couldn't imagine going with friends. I wanted to see my father's Vietnam. I knew I had to go with my father. Asking my father to return took a lot of courage. I was nervous about how he would react. But I was encouraged by the strides he was taking on his own in rediscovering his past. He had begun attending Khe Sanh Reunions, which enable Veterans to rekindle ties with the brothers they fought so valiantly to protect. It was at a reunion in 1996 that he met Ed Zimmerman. "Zimmo" was awarded a Bronze Star for his bravery in saving my father's life the night he was shot. That was the first time the two had met since April 7th 1968, the day he was shot.

During a conversation with my father while I was in Japan, I asked him if he'd ever want to return to Vietnam. It was then that he told me about his desire to return to Vietnam and more specifically Khe Sanh during peacetime. I was elated to hear this response and then asked him to accompany me. We were both overwhelmed at the possibility and the uncertainty of planning such a trip. For Father's Day last year, I sent him a Vietnam travel book. We began planning for our trip the very next day.

We arrived in Vietnam on March 18th, 2000. In the following two weeks, we traveled from Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) up North to Hanoi. Along the way we met many curious and friendly Vietnamese people. Some took us into their homes and others shared their life stories with us. All of them had stories about the "American" war. All of them continue their struggle to survive in a country marred by poverty and corruption. All of them touched our hearts in a way that will never be forgotten.

During those two weeks we visited Saigon, DaNang, Hue, Dong Ha, Khe Sanh, Lang Vei and Hanoi. After spending three emotionally and physically challenging days in Saigon, we escaped from the city and arrived at the beautiful beaches of DaNang. My father didn't realize we were staying on China Beach until he looked out of our hotel window and instantly recognized Monkey Mountain to the North, where he had done many patrols. It was hard to believe that 30 years earlier, this same beach was littered with armored tanks and overflowing with American soldiers. The pristine coastline is now littered with hand-woven, circular fishing boats, although my father did find a rifle butt lying in the sand.

While sitting on China Beach, I was approached by an amiable looking, broad-grinned Vietnamese man. He politely inquired about our travel plans and offered his services in helping me accomplish them. His knowledge of the area was impressive and his sincerity was refreshing. He thought we were traveling alone. When he met my father he was impressed that we had traveled to his country together and that my father was sharing his past with me. After spending one day with Van, we hired him to drive us all the way to Khe Sanh. We were together for the next 6 days.

During those days I learned more about Vietnam than I had ever hoped. Van is an honest, hard working, intelligent man who was prohibited from attaining a salaried position because his father was an officer in the South Vietnamese Army. Both he and his father had been imprisoned in "Re-education camps." Van was imprisoned for 3 years because he tried to flee Vietnam by boat at the age of 16. Van's presence was a blessing and our friendship continues through letters since leaving Vietnam.

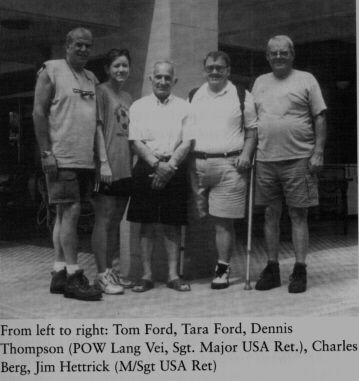

The

same night that we met Van, we met three other American Veterans who had just

come from Khe Sanh. Charles Berg, Jim Hettrick and Dennis Thompson were all

friends from their days in the US Army Special Forces. Charles Berg was a

Sergeant in FOB-3 at Khe Sanh and has been returning to Vietnam for years. He

helps the Bru tribe, a minority tribe located near Khe Sanh and the Laos border,

in digging wells and education. My father had already met him at a Khe Sanh

reunion and I remembered reading about his efforts in a magazine. I was shocked

though, when I realized that he was missing a leg. Jim Hettrick is a retired

Army Master Sergeant and Dennis Thompson is a retired Sergeant Major in the

Army. Dennis Thompson was captured in the battle for Lang Vei and was a POW for

61 months. He had been captured 4 times yet managed to elude his captors for 8

days, living without food and suffering from septic wounds while trying to make

it back to the Khe Sanh base. Coming across Veterans on the same mission as us

was a shock, in and of itself. But after hearing their stories, I realized that

I was in the presence of true American HEROES. For the first time, I was able to

see my father as a soldier. I looked at these great men before me and I was

overcome with a feeling of pride. A pride so thick, causing a lump in my throat

and tears in my eyes. I watched these men as they embraced like long lost

brothers with the moonlight dancing in the tears in their eyes.

The

same night that we met Van, we met three other American Veterans who had just

come from Khe Sanh. Charles Berg, Jim Hettrick and Dennis Thompson were all

friends from their days in the US Army Special Forces. Charles Berg was a

Sergeant in FOB-3 at Khe Sanh and has been returning to Vietnam for years. He

helps the Bru tribe, a minority tribe located near Khe Sanh and the Laos border,

in digging wells and education. My father had already met him at a Khe Sanh

reunion and I remembered reading about his efforts in a magazine. I was shocked

though, when I realized that he was missing a leg. Jim Hettrick is a retired

Army Master Sergeant and Dennis Thompson is a retired Sergeant Major in the

Army. Dennis Thompson was captured in the battle for Lang Vei and was a POW for

61 months. He had been captured 4 times yet managed to elude his captors for 8

days, living without food and suffering from septic wounds while trying to make

it back to the Khe Sanh base. Coming across Veterans on the same mission as us

was a shock, in and of itself. But after hearing their stories, I realized that

I was in the presence of true American HEROES. For the first time, I was able to

see my father as a soldier. I looked at these great men before me and I was

overcome with a feeling of pride. A pride so thick, causing a lump in my throat

and tears in my eyes. I watched these men as they embraced like long lost

brothers with the moonlight dancing in the tears in their eyes.

At that moment I wanted to reach in and wipe away their memories of the war. I wanted to take away their anger, guilt and pain. For in those brief moments, I was able to see the young, frightened soldiers they once were and the hardened, mature men they have grown to be. Through the tears and the pain, I still felt their PRIDE. You saw it in their eyes and you saw it on their faces. They believed wholeheartedly in fighting for their country. The character amongst them was powerful and it was a moment that I will never forget. After meeting these men our spirits were boosted. And the goal of reuniting my father with Khe Sanh was in sight. On March 28, we finally arrived. It was hard to imagine that 32 years earlier my father was living in the hills that now looked so beautiful and peaceful. Nothing is left of the combat base except for a small building which serves as propaganda-filled museum. The information depicted was so disturbing that I was moved to tears. For my father's blood was spilt on this land and everything written in the museum was nothing more than Communist lies. We left the museum quickly and my father pointed out the remains of the airstrip, which was vital for the soldiers survival in 1968. On January 21, 1968, a week before the TET Offensive began, the siege on Khe Sanh started. My father arrived about a week after the siege had begun. Khe Sanh was in such a precarious situation that convoys weren't able to re-supply the men with food or ammunition. Their only means of survival was from the sky. Cargo planes carrying men, food and weapons often came under fire and airdrops were sometimes all that could be done. The Marines had no choice but to "dig in." Unknown to my father at the time was how dangerous a predicament he was placed in. President Johnson followed the developments at Khe Sanh closely and vowed never to lose the combat base. At one particular time it is estimated that more than 30,000 North Vietnamese Army Regulars had surrounded the American base of only 6,000 Marines. In order to defend Khe Sanh, the US mounted the most intense bombing in the history of the war. The equivalent of 5 Hiroshima-sized bombs were dropped within a mile radius of Khe Sanh. General William Westmoreland even considered the use of tactical nuclear weapons. The siege lasted 77 days and in the end, the combat base was still under American control. It was near the end of the siege that my father was shot while trying to rescue a corpsman that lay wounded in the enemy's lines. After 6 weeks of operations and physical therapy in Japan, he was back on the front line where he remained for the rest of his 13-month tour. Thirty-two years later, I stood on the hard red clay earth with my father trying to imagine the chaos that once enveloped the area. None of the stories my father had been telling me before our arrival seemed plausible for the mountainous area is serene and peaceful now.

Moments after leaving the museum, my father pulled out an old map of Khe Sanh and with his compass we headed into the coffee plantations that now surround the area. When we emerged from the plantations we followed a dirt road that split the mountain range. We followed this road, which didn't exist 32 years ago, as my father pointed out the different hills that he remembered and the numbers that were used to identify each hill; 950, 1015, 558, 861, 861a, 881 and hill 700. We also passed a schoolyard and met up with a group of 15 middle school students who were walking home for the day. Our methods of communicating were restricted to sign language and gestures. It was quite easy for them to understand that my father was a GI. We walked for over an hour with the students following our every move. When my father stopped to tell me stories about the different hills or to take pictures, the children would stop and giggle. It was quite a moment when my father pointed out hill 700, that was the hill that he was shot on. It was mid-afternoon and the sun was glaring down on us. The heat was oppressive and the air was stagnant. As he recounted the story, I closed my eyes and tried to imagine the horrifying scenario. The way the hills bled into one another enabled me to picture the constant danger that lay beneath the thick brush. But I couldn't imagine the sheer horror and terror felt by all that were there. Neither one of us could believe we were there. Nor could we comprehend the entourage that now followed us. The children's nervous laughter was infectious and their curiosity has becoming. Their presence was comforting to me as it was a constant reminder that life in the barren area did go on.

We stopped our trek once we reached their village. The children were part of the Bru tribe, the people that Charles Berg helps. Their tiny houses are made from bamboo. There was no electricity nor was their running water. We stood in the ville and received curious smiles from small children and older folks alike. My father paused and stared off into the hills. I knew that he was tempted to run back into the hills to reclaim apart of his youth that he had tried hard to forget. As I stood there watching him a wave of emotions came over me. I was so proud of my father for returning to the land that took the lives of many of his comrades and nearly his own. I also felt extremely lucky to have a father so willing to share such a painful part of his life with me. We stood there for a few minutes then wiped away the tears, said goodbye to the children and headed back to the base.

From Khe Sanh we drove out to Lang Vei where Dennis Thompson was captured. Bomb craters pockmark the earth and banana trees thrive next to crumbled bunkers. My father told me the story behind Lang Vei and again I was moved to tears. In the final days of our trip, we visited the infamous Hanoi Hilton where Dennis Thompson was imprisoned as well as Sen. John McCain. We also visited Ho Chi Minh's Mausoleum. It is here that the embalmed former Prime Minister of VN has rested since his death in 1969. Hordes of Vietnamese people flock to his tomb on a daily basis. It was strange walking by the man who was once at the center of the Vietnam conflict, but died before witnessing his dream come true of Vietnam as one country. I couldn't help but wonder if the dire straits many Vietnamese live in now is what he wanted for his country.

Vietnam is a beautiful country with a fascinating ancient history. Although extreme poverty and corruption hinders its beauty. There is no animosity held towards American tourists or returning American Veterans. POW Dennis Thompson remarked, "Everyone and everything in Vietnam has moved on, but us. They have gotten over it, so why can't we?" This statement struck a chord in my heart and made me wonder why we (Americans) can't get past the Vietnam War.

From my travels and research, I feel I can understand the fear that communism created in the 1960s and the political reasons why we entered the war. I can also understand why many Americans protested against the war. But I cannot, nor will I ever, understand why America's bravest were spit on, defamed and deemed morally bankrupt by their peers upon returning to their country. For there is nothing immoral about standing up to serve for one's country. Three million brave men and women returned from Vietnam to have their character questioned and their voices silenced. Thirty-two years later, my father is finding his voice, as many other veterans are too. Vietnam Veteran Association memberships are rising. Enabling veterans from all over the country to come together to find long lost comrades; to laugh, to cry and most importantly, to remember.

On behalf of my generation, I would like to support Veterans in sharing their stories and experiences with others. America needs to hear about the individual sacrifices that each soldier made in his life. The heroic stories about young men and women risking their lives to save others are inspirational.

Vietnam will always remain an integral part of my life as well as the lives of many other Veteran's children. However, many of "us" haven't learned about Vietnam. We are curious about our fathers' experiences and their lives, but we don't know enough to ask. I urge educators to find the importance of teaching this chapter of American history. I am lucky that my father has broken his silence. I am inspired by his life and by the lives of other Veterans we I have met. For I have learned the value in teamwork, perseverance and strength. For standing fast in the face of adversity, fear and pain. And for knowing that 1 need not be ashamed of fighting for what I believe in. That is what I've learned from my father, a Vietnam Veteran. For better or worse, his experiences in Vietnam have influenced my own life. Rediscovering his past together has helped me discover my own future. Those are the lessons we've learned from Vietnam.

Thanks Dad and WELCOME HOME.

ED NOTE:

Tara Ford is a 23-year-old Lindenhurst (New York) native and graduate of the

State University of New York at Albany. She is currently teaching English in

Japan. Her father, Tom Ford of Lindenhurst, served in the Marines in Vietnam for

13 months.

Tom Ford served with F company 2/26th

Email: [email protected]

![]()

It is rarely comforting to recognize that the dubious distinction of participating in the entire siege fell to our lot. Those were the most desperate days of my short life, up to that point. Presently, I feel ancient. I have become a pastor by trade in the ensuing years. I am currently unemployed because the war has invaded me to the point of ministerial distraction and dysfunction. Thus, this sabbatical "year" has left me with time to ponder, to muse over the concept of meaning and the war for me personally.

Much of the human philosophy that is penned in the pages of the Red Clay magazine leaves me cold or puzzled and especially saddened. I move away from too many of the articles and poems more hurt than before I mentally entered them. Many of us are left to the questions of what do I make of those days, now? What did they really mean? Was the death and destruction really worth the effort expended in the larger scheme of things ? Why is my life coming unglued after so many years? I'm sure none of us would have retreated an inch looking at the small picture we were given of things then. On my own, I come to confused reasoning; muddled thinking or no "comment." I feel incapable of discovering "true, truth" as Francis Schaeffer called it. My unexpected and unscheduled sabbatical has shown me who I really am, as a person. I do not like what I see. I am left staring at the effects of my falleness[?] and Khe Sanh upon me. Nothing outside of Scripture that I read satisfies my soul, and I read voraciously as I am able. My studies in Seminary and out have proved vastly "thin." So I am left to find meaning for that year of unorganized chaos as I can.

I am trying not to speak as a professional clergyman. I am speaking as a human being, hurt deeply as a former Marine. I desperately need answers; real "meat" for thought that feeds and fuels my inner man. "Textbook" answers leave me flat because textbook writers seldom "lived" as we did. None of my school mates, almost all younger than I, or my fellow pastors know anything of how to respond to my desperation. And my fellow Marines are often as confused as I am in these weighty matters. In other words, shut up. Eat, drink and be merry because there are no real satisfying answers out there. There is no unguarded truth to be had except as you make it yourself. Please don't bring your dead Marine buddies in here." I recoil at that. I found it waiting for me in the church as well as grad school as well as at work.

Now, so no one will wonder if my search is purely existential and vastly unintelligible, I believe there is an answer for "those days." A meaning, if you will; true truth. I stumbled across it in conversation but left it alone to stew on its own, in its own juices. But I keep returning to it. "If I make my bed in Hell, You are there." David, Israel's warrior King, penned those words. Having studied the subject for years, I am convinced that Biblical Scripture is inerrant truth. So I can trust its words. Not everyone is so inclined. I would ask you to hear me as a man who is hurting, in need of a healing salve. This is what I believe I have found.

I return to those words because they tell me that my God, Jesus Christ, went before me to the hell of my war. Let's settle there for a moment. I did not realize that for some 30 years, I believed that God was absent from the Vietnam I knew and was avoiding. He wasn't there. Why would He want to be in Hell ? All those years I thought I was alone with 5500 Marines. Where did I think God was? I thought He was at least on R & R. Hell is no place for Deity. That's only logical but it's not good theology. God, the True God, says He was there on all those rainy ambushes; all those days of incoming; all those days of hunger and sleeplessness and so much more. We made our beds in Hell and He was there or He's a liar. So, if God was there, Jesus Christ, by reason of His Personal Presence, was there. The place has meaning because God has meaning or He isn't God. I have to deal with that. Vietnam had meaning, not because of who died, but because of who was there. Logic? Biblically so. That means I find truth where I didn't look. I kept looking at the pain and death for meaning. Not in a Personal Person.

Now, just set all the terrible things that we experienced aside for a moment. Someone in time-space history said that God was where I was convinced He wasn't; didn't want to be; had no place being. Is that possibly true? Was He there in Vietnam? With me? I'm not asking you the question. I'm asking myself the question. I desperately need to know. Was I left hanging; all alone? Or was there some reason why I got out, alive? The questions won't go away. I can't defer to why someone else didn't make it, but was God possibly there so that He is the Personal reason I made it? I am perplexed. Either I have to alter my preconceived ideas about God and Vietnam or remain rigid and my existence sadly meaningless.

If God was actually there on the battlefield, then the killing ground, the place of unspeakable terror and horror, was of necessity, holy because God is Holy. It was a place set apart, conquered, if you will, by the very presence of God. Christ sanctified or set apart Vietnam for me to redeem me from it via His

Personal incarnation there. What a mouthful. I have trouble with a place of death being holy; holy to anyone, much less God. But I still have to deal with the implications of the statement, "If I make my bed in Hell, You are there." That is to say, without Vietnam, I would not have come to put my trust in Him as the personal God of the battlefield as I did in 1972. Now, that is not a leap. Such truth doesn't make God a monster, it simply gives the place of madness real, true meaning. Doesn't it?

Do I still hurt? Yes. Do I still have bad days? You bet. Too many of them. Is life still a kind of hell? Well, I went to 4 years of college, 4 years of Seminary, 8 years of pastoral ministry and 3 years of Campus Crusade for Christ. Now I'm sitting on the bench. I've been in the hospital 3 times, all PTSD related. You tell me if life is still a kind of hell? My wife wants to do me in some days the way I act. And yet, it has meaning. God is still the God who is with me when I make my place in hell. Semper Fi.

Jim Carmichael

Echo, 2/26

861 Alpha

60mm mortars

![]()

Kenny Orton and I had lived in the small summer resort town of Guerneville, California. Guerneville is located on the Russian River seventy miles north of San Francisco. We weren't real close friends like my buddy George and I were, but we always seemed to be hanging around with the same crowd of kids. Kenny had been raised around Guerneville all his life, but I'd only lived there during seventh, eighth and ninth grades. We had moved there shortly before my Dad retired from the Army. He had been stationed at Fort Mason in San Francisco.

Kenny, George, Jessy, Steve and I were the local terrors of the seventh grade. We all hung out together, and would for the next few years. One good thing about living in a place like Guerneville was there was always something to do and ways to get into trouble! The bad thing though was everybody always found out when you did something wrong. You couldn't get away with anything in that small summer resort town!

Kenny was a short skinny kid who was pretty much a follower. If a group of kids were hanging around Kenny would always be there, but he'd be standing back just a little. He was never the kid in charge. Kenny's father owned Johnson's Beach. It was a small section of sandy beach located on the Russian River and was directly across the street from my house. That's where I met Kenny in the summer of 1961. I knew some local girls who worked in the snack shack at Johnson's Beach and I'd spend a lot of my time there trying to act cool. Kenny was always running up and down the beach yelling and complaining about having to load little kids into paddle boats his father rented or about having to unload supplies at the snack bar. He just wanted to hang around the girls visiting his father's beach. Work was the last thing on his mind!

It was a known fact that Kenny was always about one step away from getting into trouble. I was usually only one step behind that! While in the eighth grade, Kenny, Steve and myself got caught borrowing our elementary school's pick up truck. They always left the keys in it so we would take it out for a joy ride on the many back roads around town. We got away with this for many a Friday night until one time we forgot to turn off the headlights. By Monday morning the battery was dead! To this day I don't know how we got caught, but by ten in the morning we were all standing in front of the principal. Punishment was swift in those days. Within the hour we were all bending over holding our ankles as the giant wooden paddle with the holes in it rang out in the name of justice!

Freshman year found us at Analy High School in Sebastopol, twenty-seven miles from Guerneville. Kenny would always show up at my door looking for a ride to school. It wasn't cool to ride the bus. Kenny never had his own car, but could always be found sitting in the back seat of someone else's. Every morning it would always be the same. Kenny would start with, "where are we going today?" Not, "lets go to school," or "hurry up, we'll be late!" It was true, most of the time and for sure on Fridays, my old blue 1951 Ford (it had "Mr. Blue" written on each front fender) just couldn't seem to head in the direction of Analy High. Instead it headed toward the ocean, fifty-miles in the other direction, stopping in Guerneville only long enough to pick up more kids. That was the Kenny Orton that I knew!

I left high school in 1963 during my junior year. I was so excited about joining the Army, I don't even think I said good-bye to Kenny. Joining the Army was something I had always dreamed of doing that I didn't even think of my school or childhood friends.

The next time I saw Kenny was six-years later in the summer of 1969. I was standing in the motor in a place called Xuan Loc in a strange country Vietnam. I was watching my crew changing a Worn out road wheel on our tank when I heard, "Jack? Jack Stoddard, is that you?"

I turned around to see a young skinny soldier who was about three inches taller than me just smiling. I knew that smile! My mind searched all the faces from my past. Then it clicked! "Kenny, you old son of a bitch! What are you doing here?" It was great to see him. I couldn't even remember the last time that I had run into anybody from home. And to find an old friend in Vietnam was twice as nice.

After work we spent most of the night drinking beer and talking about the good old days on the Russian River. Kenny updated me on the happenings of all our friends. It seemed like most of them were in college trying to avoid the draft. That kind of upset me, but at least my friend Kenny was in the Army. It felt great that he was here with me. We spent a lot of time together and soon became even closer then we had been back in the world. I think the 'Nam had a way of doing that.

We were in different units, me as a tanker, and Kenny working in the Chemical Corps. His job was to help purify the drinking water for our whole base camp. Kenny wanted to be a combat soldier like me, but I told him his job was even more important then mine. A lot of men counted on that water and without it we couldn't do our jobs. I joined the ARPs about three months later. Kenny also tried, but his commander wouldn't let him go from his unit. It really upset Kenny as he wanted nothing less than to get into the action. He still wanted to become a combat soldier! He wanted that first fire fight.

We still remained good friends and would get together about once a month. I was now stationed out of Bien Hoa and Kenny was still at Xuan Loc. Six months later I would leave Vietnam and once again I didn't get to say good-bye to my old friend. It was December 1969. Merry Christmas, Kenny. A soldier like me didn't last long back in the world and by March 1970 1 was once again riding a tank through the rice fields of Vietnam. This time I was way up north in a place called Quang-Tri.

About halfway into my second tour our unit was working around Khe Sanh. Just holding onto this piece of land had a reputation of being hard and dangerous work. Myself and my crew were just about worn out from the long hours, lack of sleep and constant off and on contact with the enemy. It had been a really long two weeks and we had just pulled back into the base camp and parked the Double Deuce next to the shower point. I was in the process of getting my shaving kit from the bussel rack of the tank when I heard, "Jack? Jack Stoddard, is that you?"

Right away I recognized the voice and turned around expecting to see the same old friend I had left in Xuan Loc nine months earlier. What I saw sort of looked liked Kenny only much older, tired and scared looking! I was taken aback by my friend's appearance, but I still managed to jump off of my tank and give this stranger a big and long hug. My awaiting hot shower no longer seemed important to me. I yelled up to Jim, my gunner, to throw us down two cold beers from our Mermite can.

Kenny and I sat on a large boulder and sipped our beers in silence for what seemed like an eternity. Then Kenny started to speak. He explained that he had finally become a combat soldier. He also had extended in Vietnam and had volunteered for sniper school. You could hear the excitement in his voice as he slowly started to sound like the Kenny I had always known. He told me all about the special weapons he so proudly carried and the training they had to go through. Then he started to shake and turn away from me as he started to tell me his terrible story.

My dear friend Kenny had just returned from the worst mission in his life. I really don't want to tell you his story. I can't, not even today. But what I can tell you is that four snipers had left Khe Sanh the night before and early this morning only Kenny had walked back in. He was now crying and asking for my advice on what he should do next. Should he quit or go back out? I took a long drink from my now warm beer. I told him if it was me I'd have to go back out at least one more time. Kenny just sat there nodding his head, yes, as if in agreement. We talked for a while longer, but I could see that my friend was far away in a different place and time. Soon Kenny, without saying a word, stood up gave me a long hug and walked away. I never saw or heard from him again.

In 1998 while doing research for my book, I found the phone number of my friend George and decided to call. After a while the conversation turned to Kenny. George said that Kenny had called him the year before around Christmas time. Kenny had made it home from Vietnam and graduated from college four years later. He became a successful design engineer. George said everything was going well for Kenny until he started getting flash backs of Vietnam, then everything fell apart. He had become an alcoholic and lost his job, home and money. George thinks Kenny lives with his parents somewhere in California. He wouldn't leave his address or phone number with George.

I miss that skinny kid, even if he did manage to keep me in constant trouble! I'd give anything if it could be the way it used to be. Kenny and I skipping school, laughing and telling jokes as old Mr. Blue carried us off to the ocean.

The preceding piece is an excerpt from the book "What Are They Going To Do, Send Me To VietNam?" Written by Jack Stoddard. If you enjoyed this chapter you can purchase the entire book from Jack at: Sunrise Mountain Publishing, 5397 E. Washington Ave., Las Vegas, Nevada 89110. Phone: 702-459-4233. E-Mail [email protected]. The price is $16.00 which includes shipping and handling.

![]()

On a night quite dark, I sat and waited your coming. Who you were, I didn't know then, and I don't know to this day. Although since our meeting that night, you have been quite a part of my life. Many a time I have sat and talked to you; invited you into my home; shared the tales from that long ago past. I had you at quite a disadvantage that night. Waiting for you wasn't an accident, or a chance occurrence. You had done everything but issue me a written invitation, complete with road map. Broadcasting your coming appearance, we were well prepared to take you up on your offer. As I sat and waited, I gave very little thought to you at the time. Part of my thoughts drifted to my far off home. A home alien to the lifestyle I now led. Changing to memories of childhood friends whose antics seemed more like fairy tales. All the while though, a part of me kept attune to the serenade of, the night all around me. Taking nothing for granted, experience had given insight as to what belonged and what didn't. What didn't; did not necessarily mean danger, but it did bring instantly a return to complete alertness. Erasure of all non-vital senses. Quickly the mind went to work evaluating the intruding clues. What is was; how far away; the duration of it; the direction; the possible relationship of what I was doing out there. Without words everything was gathered, sifted, and rated. Wordlessly shared with the companion by my side. Thus it was the barking of dogs let us know you were on the move long before your arrival. Very soon, I knew with a certainty that my wait wound not be in vain. What little alterations needed to be made to my position, I made, and then settled down for the final wait. No more letting the mind drift; no more movement. My comrade and I were as still as the night had become around us. In the darkness not ten feet away, I watched the first of your party pass silently by. Armed and dangerous, we were not concerned with him. We had come here for you, and patience gained from many other nights like this, kept our growing highs in check. And then--then it was your turn. Very close, carrying rice, you and your remaining comrades, made your last fateful steps. They brought in range of two M16's. Lightweight, deadly, you had no inkling they were there. Both sighted, so that their paths of human destruction would cross just where you happened to be. I imagine that a few of the people with you were also your friends, but that, like so much of your life, is only conjecture on my part. Your small party crossed into our established killing zone. I knew I had you. No doubts, no qualms, no misgivings. It wasn't hard at all. The squeeze of the triggers made no sound, and by the time any reaction on your part was possible, the first magazine was empty and the second finishing the task. The joint effect of our actions was devastating. I was entranced by consequences of what was happening. The bullets swept your group like a tractor at harvest. Only you were caught in the criss-cross of our two weapons. Like a puppet on a string, your body jerked and danced. A slow motion performance, the bullets keeping you up. Unable to fall, my fascination grew. Never had I been privy to such a private and intimate occurrence. The rice you had carried, pitched and flew to fall; again and again. A pseudo snow like vision to blanket your diminishing stage. I saw and remember quite literally everything that night. Everything but your face. Everything but who you were. But then again, maybe I did not want to see it. I didn't hate you. I didn't even know you. Up until that time, you were a nobody to me. I had no regard for your emotions, your feeling. No respect for the same fear that you and I probably shared. Never thought about your home and family; the love that ended for them that night. No, to me you were only a job that had to be done, a stranger who had come a calling. And I had answered in a very deadly way. Much more deadlier than I had planned. Somehow with the passing of your life, I realized the futility of mine.

A year and a half of my young life, I had spent seeking to end the lives of others. I had seen blood run like water from a spring. Listened to the sounds of the maimed and the scared. Walked many a step hoping each would not be the last. And now, this night, with the chance meeting with you, it all reached my own private crescendo. I knew inside that my usefulness in this game was over. Just as it was for you, it now was for me. In that instant I lost the edge that had protected me for so long. My mind, my body were tired. Slowly I stood, holding my empty weapon in one hand, a full magazine that would never be loaded in the other. With a resigned relief I faced in the direction of your point man. Already I could see the evidence of the gun he carried. The tracer rounds gave his position away, but I no longer cared. Closer and closer, the points of light came. There was no fear, no anger, no pleading to keep on living. Just a waiting release from all the pain and anguish. A rest from the strain that had so long been kept in check. But alas my dear friend, your destiny was not to be directly mine. The bullet I sought, came and went. And I still stood. Stood shocked that I lived, stood shocked at my wait. A hammer blow had hit me, and brought me back to the living. The suddenness and force of the blow, a message to run and live. And so I ran, a fist sized hole in my back. A permanent reminder to carry, to remember you by. Ran with the vision of our meeting, with the thoughts of my deed, ran with my blood watering the ground. Seeing you now, as I saw you that night, you have not aged, neither have you changed. We have become good friends discussing so much. Many a night we have shared without light. So come in and enter, any time that you wish, my house is yours, and the bond between us means so much.

Talis Kaminskis

![]()