ZEN : TO CUT A LONG SATORI SHORT

![]()

| BIG PICTURES of Japanese Buddhism |

|

Satori:

Japanese Zen keyword that means 'enlightenment';

Zen Buddhism was such a raging fad in San Francisco around 1960's, that no one is likely to need any more explanation of it today. People whose mission on this earth was to roam around aimlessly, get into hangovers that lasted for weeks, and write uncouth poetic attempts in the scanty soberer hours, such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and so forth, had left you enough Zen to misunderstand for life. But Zen used to be nowhere around pop culture, and even to misunderstand it you would have to climb mountains and descended gorges and swam mosquitoed rivers. The Beat Generation dug their Zen secondhandedly, i.e. from Japan. The Japanese Zen of course originated in nowhere else but China. And China was only able to concoct Zen because of India. The latter exported its best, a Buddhist preacher named Bodhidharma, to China in the year 527. This great man (literally) was the very first Zen Master in the Milky Way. Bodhidharma got off the ship in Guangzhou in the end of summer that year, then immediately endured an equally hazardous trip (compared to the sea voyage and its suspicious catering service) to Nanjing, the capital city of the Liang dynasty of Southern China. He did so because the Emperor, Liang Wuqi, was such a pious Buddhist (this religion came there in 200's), and summoned the Indian to further enhance his chance to attain Nirvana. According to the Zennists, the first encounter between them happened somewhere near the excessively-groomed bamboo grove at the palace, whereat the Emperor said "I have done a lot of good things in my reign here. I cause new temples to get erected, I've been taking care of priests and monks and preachers, and so on. Would you assess now how much goodness I have created?" To which the venerable (i.e. however irreverential this observation be, scary) holy man answered: "WHAT GOODNESS?" and lo and behold Zen was born, because nobody but a Zen Master would have talked like that to an Emperor right in front of dozens of palace guards without losing his head. However, Emperor Liang saved face by sending Bodhidharma away. The initiator of Zen then sailed across the river Yangtze and landed in Northern China, which was ruled by the Eastern Wei dynasty at the time. There, he came to a Shaolin temple on Mt. Song. And sat down facing the wall. And that was, for a long time, all. One of those silent days, a rather young monk named Shen Guang came by and insisted to turn Bodhidharma's face away from the wall. He said he wanted to be a pupil. It was winter, and Shen Guang was, by the time Bodhidharma reluctantly responded to his plea, kind of frostbitten. And he was refused anyway. "One can be Buddha in no time!" growled Bodhidharma, "But less than the greatest spirit will never make it in a lifetime!" To show the greatness of his spirit, Shen Guang cut off his frostbitten left arm (nobody could tell me where did he get the blade, so I can't say either). That was good enough for Bodhidharma. He accepted him as a pupil, and renamed him Hui Ke. Afterwards, a few other pupils came, and they all stayed together as Bodhidharma's private class until the year 532. That year, the Master went back to India. So far, it is China we're digging; so Bodhidharma doesn't have anything to do with Japan, right? You have never encountered the name 'Bodhidharma' in any Japanese Buddhist text, site, blog, book, movie, etcetera, right? Right. You know why? Because in Japan they don't call him 'Bodhidharma', despite the fact that it is his name. The Japanese call Britney Spears 'Buritenai Supiarse'; so, what could have stopped them from warping the name of THE Buddhist who's responsible for the Japanese Buddhism to begin with? This is what Bodhidharma has become when imported from China by the Japanese:

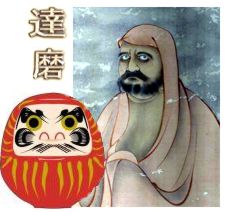

D A R U M A The

pic at the background is a portrait of Bodhidharma by a Chinese artist.

Luckily Hui Ke didn't know anything about that. Anyway, he got the legacy as the Second Great Master of Zen after Bodhidharma went home, and Hui Ke continued teaching, until he found a spiritual heir, a man who used to get shunned because of leprosy, named Seng Chan. This was the Third Great Master of Zen. One day, the new Great Master talked with a very young Buddhist monk who appeared to him to be really clueless.

The little monk, predictably, attained enlightenment there and then. He became the Fourth Great Master of Zen, and got a new name, Dao Xin. In time, he gave his robe (I forgot that there was a hereditary robe in this sect) to the Fifth Great Master, Hong Ren, who, when the time came, gave it to the Sixth Great Master, Hui Neng (638-713, see previous page for picture). Hui Neng's family name was Lu, born in the town of Lingnan, at the province of Guangdong, in Southern China. His dad used to be a rather high-ranked officer of the state. For some reasons, he was sacked and degraded into ordinary citizenship, at which point he died brokenhearted. Hui Neng was still a little boy. He got to support his mom by selling firewood and doing errands for the townsfolks and temples. So he never went to the Confucian school, and had to learn the ABC's and 123's by himself stealthily in-between hard jobs, which didn't happen often enough to give him mastery of the complicated Chinese system of writing. One day, he overheard someone reading the Diamond Sutra, that was written by the fifth Great Master Hong Ren. He decided to seek the man, and went to Henan in Northern China, far away from his hometown -- he got to walk for 30 days to get there. 'There' is a monastery named Huangmei. And he was treated as a barbarian there, for the Northern Chinese considered Southern China as some sort of neverland of the ignoramuses. Even Hong Ren himself said, "You're just a barbarian from a little Southern town. How in the world would you dare to wish to be Buddha?" and told his pupils "This barbarian has a sharp mind and a sharp tongue. Let him work the hardest." Eight months later Hong Ren announced that he would step down and give his robe to the next Great Master of Zen. He would do it the hip way: via competition. Everyone was told to write the characteristic Zen lines named gatha, and he would decide the winner from the result. At the time, the deputy teacher Shen Xiu was thought to be the heir already, so no one dared to challenge him. Shen Xiu wrote this on a wall: "The body is the tree of enlightenment. The mind is where the clear mirror stands at. Wipe it carefully everyday so it will keep on being clean, unpolluted by worldly dust." Hui Neng couldn't write his own name, let alone a philosophical musing. He asked someone to write next to Shen Xiu's lines: "Essentially there is no tree of enlightenment. There is no clear mirror and there is no place for such a mirror to stand at, either. Since the beginning everything is nothing; where the heck dust can get on?" It was the winner, of course. But Hong Ren sensed some unrest among his pupils, and pretended to scorn Hui Neng's gatha as something so un-enlightened that he even told them to clear the wall of it. But he did give his robe to Hui Neng, telling him to leave the monastery because someone might kill him for it. Hui Neng went away, and stayed in hiding for no less than 15 whole years, eluding the hunters for the robe who vied to cut his head off. In 676, Hui Neng went to the temple of Fa Xing in Guangzhou. That day a locally-celebrated Zen preacher named Yin Zhong was scheduled to give a public lecture, so people came flocking to the vicinity. It was there that Hui Neng 'beat' Yin Zhong in the typical Zen 'wordplay' to gain enlightenment (by Q&A known as 'koan'). Yin Zhong admitted he lost, and became Hui Neng's pupil. Then Hui Neng erected his own monastery in Caoxi, which temple was called Bao Lin. From this moment on, Hui Neng was known as the Great Master of the South. There was, as the term implied, the Great Master of the North, who happened to be the same Shen Xiu that you saw earlier. Shen Xiu enjoyed prosperity because he was favored by one of the most notorious Empresses of China, Wu Zetian, who reigned by the name of the Tang dynasty at Chang'an (her capital city would be copied by the Japanese who produced Nara in 600's). The difference between the two was, Shen Xiu applied vigorous meditations -- he said this would give you enlightenment step-by-step. Hui Neng never told his pupils to meditate like nuts; he said enlightenment is something that happens at once and directly attained at. The latter left five Chinese Zen Masters after he's gone: Nanyue Huairang (677-744), Qingyuan Xingshi (660-740), Yongjia Xuanjue (665-713), Nanyang Huizhong (677-775), and Heze Shenhui (670-758). Afterwards, there was the greatest of these post-Hui Neng Masters: Mazu Daoyi (709-788), from Chengdu, the Sichuan province. His pupil Bai Zhang continued his school after he died. It was Bai Zhang who codified the late Master's stuff, and made Zen Buddhism a real sect at last -- by writing down some rules and drawing a clear line between Zen and the rest of Buddhism. All the rules were simple and predictable, such as "thou shalt not kill" and so forth, plus monks and priests were not allowed to watch plays and dances, wear accessories, sing, keep gold and gems, eat when it wasn't the communal time to eat, and drink any alcoholic substance. The latter had to be specially mentioned there in the string of 'dont's', because some Buddhists already thought they were sacrificing stuff by turning vegetarians as Buddhism as a whole exalted this lifestyle, so they tended to forget that booze was just as bad as meat. The most famous thing about Bai Zhang is that he espoused a total divorce from the Indian Buddhism in practical daily living: "You got to work for your food," he never got tired of saying; "Stop begging for alms to innocent people. Otherwise you're nothing but a parasite." (Amen, I say.) Bai Zhang himself worked like nobody else could. Chinese people are always famous for their longevity, in which the most senior citizens are still active, so Bai Zhang didn't really get noticed for working in the fields with hoes and such at the age of 94. But the incurably lazier people of today of course marvel at it. Hui Neng was the greatest Great Master of Zen, and the wisest, of all times. His words -- such as "'Not depending on words' is just words. You can't depend on 'not depending on words', either" -- were recorded by his pupils inside a tome called 'the Altar Sutra'. It's the only Chinese work that is universally acknowledged as a Buddhist sacred book. Anyway, life wasn't to be Zen-like in the next chapter of Chinese Buddhism's bio. There was only one dynasty reigning at the Southern and Northern China: the Tang (618-907). In 845, Emperor Wu Zhong decided that the poverty that made the eyesore everyday to him was caused by Buddhist monks, priests and preachers, who begged for their daily food everywhere around his territory. So he made his own solution of this problem. He burned monasteries, temples and shrines after looting their gold and precious stones; 4,600 temples and 40,000 monasteries, to be faithful to the Buddhist historians' records. More than 260,000 monks and nuns -- who used to live in celibacy -- were forced to marry someone nearest and begot a family and work like 'normal'. There were also 150,000 monks (all male) chained into the Imperial Army and Navy as janitors and such. Every Buddhist sect went underground after suffering death-blows that somehow still couldn't kill them. Every one of them, except Zen. Bai Zhang's Zen survived because everyone in the sect worked for their living. The entire Zen 'tribe' survived because they didn't have nice temples adorned with emeralds and no Buddha's statue made of gold. They didn't lament the burnt sacred scrolls, because they didn't need written words. So they still thrived even under that inhuman reign. New Zen Masters kept on being made: Zhaozhou Chongshen (778-897), Tianhuang Daowu (748-807), Longtan Chongxin (d. 838), Dongshan Liangjie (807-869), Fayan Wenyi (885-958), Yunmen Wenyan (864-949). The latter is famous because of a personal quirk: he only spoke one single word every time around. Even when teaching.

In 900, there were 5 schools of Chinese Zen Buddhism that sprang out of Hui Neng's legacy. Nanyue Huairang's Gui-Yang and Linji, Qingyuan Xingshi's Chao-Dong, Yunmen, and Fanyan schools of Zen are what people mean today when saying 'the Five Chinese Zen schools'. The five schools only existed from this time on until 1279. Gui-Yang, Yunmen, and Fanyan came back to oblivion after the end of the Southern Song dynasty that year. Only Linji and Chao Dong survived the subsequent ages. Chao Dong is the dominant Zen school in China. Linji got exported to Japan, where it was re-baptised into Rinzai. In 1185, the Minamoto clan of Japan ascended. The first of their Shoguns, Minamoto Yoritomo, made Zen the Buddhism of the warrior-class for good. Zen is also the reference for picking up family or clan crest (click here for the basic family crests of Japanese samurai clans). Why Zen? Because Zen is among others the simplest, about simplicity, and espouses something that instantly reminds you (alright, not you, maybe just me) of Protestan Ethics that the Puritans dragged with them across the Atlantic on the Mayflower once upon a time. More precisely, because only Zen could smoothly get mixed together with the original belief of the Japanese that the Chinese called 'Shinto'. The two have been so perfectly mixed-up for the last thousand of years that only certain geeks care about what differ them.

This 'Warrior Zen' or 'Samurai Zen' started when a flock of largely illiterate soldiers came to the founder of the Jufuku temple of Kamakura, Eisai, in 1215, and asked him to teach them some 'enlightenment'. Teaching them Chinese stuff would have been useless, so Eisai made it as simple as possible and tried to fit his Zen into reality of the soldiers' lives. This splashed. Hence everyone learned Zen, which, now, was something installed into the minds of people who might die in battle after leaving the temple. Zen raged in the next era, too, under the Hojo Regency, although at the same time the most quarrelsome Buddhist sect in Japan -- Nichiren (click here for history and why I said it's 'quarrelsome') -- was making its own splash. The Minamoto years were characterized by sheer impatience regarding the culture of the sedentary that had been in vogue until their ascent. They simplified everything from clothes to religious rituals. With the arrival of the subsequent Chinese export cargo, the simplicity was further boldened -- the tea ceremony, for example, which grew from elaborate to very 'whatever may', throughout the Warring States of Japan. Tea ceremonies were not, as all other samurai non-lethal activities were not, diversions from wars; their function was exactly the contrary of a diversion. They put the samurai back into focus. Zen played a great part in all this. Its unmistakable exaltation of work and scorn towards idleness fit like a pair of your very own gloves into the soul of the Japanese samurai. The Tokugawa shogunate's rule, since 1638 (after the Shimabara Catholics revolted) until 1868, was the era of idle samurai. Samuraihood was not the way it used to be, no matter how hard some Shoguns tried to revive it (without jeopardizing their position). Under the Tokugawas, Zen changed into the languid, unintelligible, artistic verbal ejaculations like you know today. Even the kanji to write the word 'samurai' then was the one that also means 'scholar' -- justifying the excessively effeminate nature of the Tokugawa warrior class, who would, all along this era, flaunt the faked and sterilized samuraihood, just as the so-called 'way of the warior' of the Tokugawa, 'Bushido', which was a mummified remnant of the real thing belonging to the pre-Tokugawa times. Click here to continue to SAMURAI ZEN and the 3 major sects of Japanese Zen Buddhism. |

Manifestations of Zen in Japan

![]()

|

Japanese Zen-Shinto hybrid architecture

Japanese

Zen-Shinto sand garden |

|

[ CLICK HERE FOR PICTURES OF THE 3 SECTS OF JAPANESE ZEN BUDDHISM ]

What Zen Really Is

![]()

| 1. | You can't even start to comprehend Zen Buddhism with scientific or empiric analysis and vivisection. Zen can only get understood via anti-scientific methods, such as intuition. The point is, as long as you are thinking of everything within the dichotomy of Object and Subject, between the Observer and the Observed, you're lost. |

| 2. | Logic runs to the opposite direction from where Zen is. |

| 3. | You can't even get started in Zen without getting enlightenment (satori) first. |

| 4. | Getting enlightened is nothing special in Zen. It is not the goal of practicing Zen, either. |

| 5. | Enlightenment is a redundant personal experience. You'll get it again and again and again and again -- until, perchance, you attain the total enlightenment like what Buddha (Siddharta Gautama) got. |

| 6. | Don't buy the misled notion that Zen is 'a Buddhist sect characterized by vigorous meditations' as many sites have been saying. That's a total bull, and I mean it. The truth is this: Zen believes that there are certain tools which can help you to get enlightened. The first and the most widely practiced is meditation, called za-zen in Japanese, AKA 'samadhi' in Sanskrit. It's just one of a set of tools. It's not 'the main tool'. And no practician of Zen meditates longer or more often than other Buddhists. |

| 7. | The function of meditation is to make you to get used to seeing reality intuitively. How do you know you are there already? Just check the symptoms; in your intuition's eye, reality looks just the way it is, un-probed at all, and let to reveal itself. |

| 8. | You are seeing reality the way it is when it ceases to be an object to your mind. |

| 9. | The second tool is intuitive Q&A, or mondo in Japanese. The function is to tell whether you have been enlightened or not. You have to answer without thinking and at once. Example: "What is a bottomless bucket?" |

| 10. | The third tool is similar, called koan. The difference from mondo is that you seek the answer for the question via meditation. Example: "The Teacher said that his burnt bones embrace heaven and earth. Who is embracing the teacher's bones?" |

| 11. | Satori or enlightenment means a whole new way to see everything around you. It is essentially an event where you find your true self. This true self is to be found in relation to nature. When you and nature are no longer distinguishable, you got it. |

| 12. | There is no such a thing as conventional piety in Zen. Meditation is of the same value as daily activities and manual jobs. |

| 13. | If you are enlightened, you can't possibly tell the experience to anyone, and you can't show it to anybody either; the tools above will only hint at it and can't help anyone to reconstruct or demonstrate it. |

| 14. | Art works and artistic biz, like short poems (haiku), pictures (sumi-e), and tea ceremony (cha-no-yu), are manifestations of enlightenment in Zen, but they can only show a very limited hint at enlightenment. |

| 15. | So it is perfectly okay if you can't understand my enlightenment and I can't make sense of yours, because there is nothing to be understood or make sense of. |

| BIG PICTURES of Japanese Buddhism |

Oda

Nobunaga IN

Zen Buddhism

and the origin of his personal battle-banner & slogan

![]()

| CLICK HERE |

| Samurai's Zen | Big Pictures | Oda Nobunaga in Zen |

Site & Rap © 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 Nina Wilhemina

All rights reserved. Every borrowed image at this site is put for non-profit educational purposes only.

HOME

LINKS

LINKS

CONTACT

CONTACT

CREDITS

CREDITS

COMMENTS

COMMENTS