Click above to return home, or click below for more information.

Chapter 1: What control was there before the Light Console?

Chapter 2: What were the reasons for the invention of the Light Console?

Chapter 3: How did the Light Console work?

Chapter 4: What was the Light Console like

to use?

Chapter 5: Why did the Light Console seem to disappear so suddenly, along with most of its ideas?

This is a copy of my Dissertation on the Light Console. Please feel free to use this information as you wish. I am always looking at adding things to the Dissertation, so if you think I have missed something, or need to remove something, please let me know, here. You may also be interested to know that I helped restore the Theatre Royal, Bristol's Light Console, with Nick Hunt as part of my Degree. I have now played Colour Music, and even used it to control a moving light.

Please also see Nick Hunt's webpages on the Light Console, here.

Last updated: 28/08/2007.

Originally completed in 2002.

Fred Bentham was born on the 23rd of October 1911 in Harlesden, Middlesex. He was very opinionated, and had many a strong word to say about lighting, he saw it as an art form. He was to work for the same company, Strand Electric, for forty years. He started work in the showroom, which displayed all of Strand Electric’s hire products. He later moved on to demonstrate the lighting that they sold, then he became in charge of a new department in R&D (Research and Development). Amongst many other things during his time with Strand Electric, he designed the Hook Clamp and produced a new catalogue for Strand Electric in 1936. Many of the items listed only existed in its pages, but could be made if and when requested. He also designed the first mass-produced lanterns in 1952, which are still in common use today.

Bentham’s biggest contribution to stage lighting was a lighting control called the Light Console, in 1934/5. The Light Console was very similar in appearance to a Cinema Organ, but never played a note of music. It used many parts from another manufacturer, and the quality of workmanship was very high. As it was not designed as a commercial control, it is doubtful that Strand Electric ever made any money on it. The Light Console was very expensive to buy and they took a long time to manufacture, so they could not sell large quantities.

The Light Console was in fact the result of Bentham’s passion and hobby of Colour Music. Colour Music involved changing lighting on a 3-dimensional object, or plain cloths and drapes, by varying the intensities of lights, in time with the moods of music, from Classical to Jazz. From this hobby, he designed a lighting control that changed the basics of controlling stage lighting forever.

I have been particularly inspired by how the Light Console was operated, and have been able to look at a Baby Light Console in much detail. Compared to a modern lighting control the Light Console’s interface seems to be simple, yet it requires a trained operator. The Light Console had a complex way of working and this was passed onto its controls. Compared with modern computerised controls, which offer just “GO” buttons, the Light Console had the ability of synchronising lighting effects with the action on stage during a live performance, which has not yet been surpassed. However, as the lighting “states” (a state, or picture, is a term for a freeze frame of a lighting design, and a cue is the transition between them) could not be memorised by the Light Console, it had to be operated live each and every performance.

There are many important dates in the history of the Light Console. In 1935, the first Light Console was made and installed in the Strand Demonstration Theatre. The first theatre-based installation of the Light Console was in the San Carlos Opera House Lisbon, Portugal in 1940, much to Bentham’s surprise “War or no war, someone wanted a Light Console!”[1] English manufacturers were encouraged to export at this time, so it is not surprising that the first is abroad, many later controls were also sold abroad. It could have been the last as well, as Bentham had been very ill with pleurisy. It was a difficult installation, due to poor transportation in the Second World War, and the language barrier. Bentham and a team were over there for six months, but it was a success.

Back in London, two bombs destroyed the Demonstration Theatre on the 10th of May 1941, but amazingly, the Light Console survived, as it had been placed under a balcony when the War broke out. This Light Console was re-installed in the Palladium later that year, where it probably became the most overworked Light Console installation. It was replaced in 1949, and the new Light Console was to last over 17 years, and carry out over 265,200 cues. The largest installation of the Light Console was in the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1950. There were an amazing 216 channels, and yet the Light Console and the single operator were able to cope. Each installation had different requirements, therefore the features available on the Light Consoles varied, but they were all essentially the same.

Chapter 1: What control was there before the Light Console?

With so many displays on modern controls, it is possible to get obsessed with the information displayed, rather than the lighting on the stage. There was hardly any information involved with early electrical stage lighting. There were considerably fewer lights, and no high accuracy dimmers available. The channels were labelled by location around the theatre, and the label was the colour of the light the channel produced. The need for circuit numbers only arose when the style of lighting changed in the 1950’s, when lights could be moved around the theatre a lot more, and Battens were not used as often.

Fig. 1. Inset: Gas Battens, Main Picture: Early Electric Battens.

Early electrical lighting was actually a

direct descendant of the gas system, which had rows of gas jets. Electrical

lamps were used instead of the gas jets to generate light. After 1920,

electrical lighting usually consisted of rows of floodlights above the stage,

called “Battens”. These Battens would later have compartments, about 30cm

square, so that each light was separate from its neighbour. This meant that

different colours could be used in each compartment, and a common system was to

have one without colour (open white) and two colours.

With open white and two colours, there

was less choice of colour, but more lights to each colour. With open white and

three colours, there was more choice, but fewer lights to each colour. Amber may

seem an odd choice, as it is not a primary colour, like the others are. It was

chosen because it could be used to create sun effects. Green would be used in

cinema lighting to allow mixing of the primary colours on plain sets for special

live shows. This variation seems

not to have been a problem, and different styles of performance would prefer its

own style of Batten lighting. The colours in the Footlights would probably have

been the same as in the Battens.

There were a few additions to

supplement the Batten lighting, namely, a few lanterns Front of House, possibly

a few Arc Follow spots. There was often the facility for practicals (a light as

part of the set that works, i.e. a desk lamp) or additional lanterns on stage

with Stage Dips. These are sockets hidden under the surface of the stage, so

that a lantern can be plugged in without a long cable. It should be understood

that the lighting at this time was very simple. As most of the lanterns were

fixed, design choices would have been limited to the colour required on stage,

therefore, there was no lighting designer, as we understand them today.

Lighting design today has lots of

options available, but there is only one person that makes them, the Lighting

Designer. Before this role was established in the 1950’s many people would

have designed the lighting, and there would have been fewer choices to make.

This is interesting because there was a revolution happening in lighting as a

whole in the 1950’s. The Battens and Footlights were becoming unpopular and

were replaced with mass-produced, and more importantly, focusable lanterns,

increasing the amount of choice for the design. In addition, the style of shows

being put on was changing to more period plays.

The original collaborative lighting design would not have ended at design, as there were many people required to operate the controls. The lighting control was often put in a perch position (a location above one of the wings). The view from here was not very good, and there are cases of lighting control being in a completely separate room, or under the stage. From the 1920’s, a theatre could have had one of many varying styles of dimmers and controls, with one thing in common, their size.

Early dimmers were very large indeed,

and some had live switches on the front. Roy Castle recalls an electrician being

electrocuted and thrown across the room while operating lighting; please see

Appendix 1 to read the entire recollection. I am confident that these controls

hold the origin of the term Dead Black Out (D.B.O.), which is still in use

today. A major development from this was “Dead Front” controls, where the

entire front panel was insulated from the conductors behind it.

Variations of this include a system of “Tracker” wires connecting liquid dimmers (which used a salty solution of water to dim the lights) to a remote control. Unfortunately, as an ideal salty solution was urine, they soon adopted the nickname of “Piss Pots”. Therefore the remote control idea might have been due to the smell of these dimmers, and not a choice to operate remotely! However, it was more common to find the control in the perch position, directly above the dimmers at stage level. Fig. 2. shows a simple liquid dimmer designed for amateur theatre, it utilises the same principal; the only difference is that proper theatres would use a wheel control, instead of the hooks.

Fig. 2. A simple diagram of a liquid dimmer.

Fig. 3. A German Tracker Wire control.

The advantage of remote control given

by the tracker wire seemed to go unnoticed. Nobody thinks to place the operators

in a location Front of House, where they can see the whole stage. This was

probably due to the high cost of routing the tracker wires from the dimmers to

the control, let alone through the theatre. Therefore, the remote control idea

took a back seat until Fred Bentham and a few more inventions outside of the

theatre came along.

The Grand Master was a directly operated, “Dead Front” lighting control, made by Strand Electric, and was the most popular control in England in the 1930’s. The principle of the Grand Master was that channels were connected to the dimmers behind the panel by a linking rod. The dimmer had 80 or more contacts that were connected to elements, or resistors, and an arm would move across them, connecting the lanterns to the elements. The dimmers were matched to the lanterns, so a 2,000-Watt dimmer had to have a 2,000-Watt lantern connected to allow the dimmer to work properly. A later invention called the “Auto-Transformer” would allow any load to be placed on a dimmer.

Fig. 4. A Grand Master Element Dimmer.

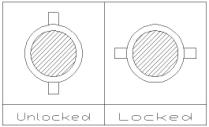

A wheel on a shaft controlled the dimmer, and a handle, which could be rotated, was used to lock the wheel onto a shaft. A Tommy bar through the middle of the handle indicated if they were locked onto the shaft or not.

Fig. 5. Diagram example of a Grand Master handle.

When they were locked onto the shaft, the channel would move when the master wheel was rotated. There was a shaft per colour in the Battens above the stage and in the Footlights. This meant there were four shafts for the open white and three colour system; in addition, there were two shafts for any independent lighting. Consequently, there was a minimum of six shafts, set around a large wheel that was turned to control the lighting change.

Fig. 6. A 60 channel Grand Master.

The sheer size of some of the Grand Masters meant it was often impossible to have only one operator. This led to the problem of having to pay many staff to control it, and if the show did not require lots of lights, or many complicated changes, then some operators would not be required, and therefore be out of work for the run of that show. Bentham’s goal was to invent a control on which one person could operate hundreds of channels, with two hands and feet, and that it was remote from the dimmers. The idea of remote control meant that the lighting operator could see and hear exactly what was happening on stage. It also meant that the dimmers could be located anywhere, often in a room of their own, near to the mains intake, creating more space at the side of the stage. This remote operation is now the base of stage lighting control today.

This is the vary basic operation for a cue on the Grand Master:

Select, and lock onto the shaft, (by turning its handle by ¼ of a turn) the channels required to move in this cue.

Select the direction of travel for the shaft.

Turn the large wheel at the rate of the cue. (The amount of force required to turn this wheel would vary with the amount of channels changing.)

De-select the channels, and repeat above process for the next cue.

There were many drawbacks of the Grand Master, and one of the most important was that it was impossible to have different channels locked onto the same shaft to travel in opposite directions in the same cue. This meant that one set of channels would have to fade, and then be released from the shaft, before the channels going the other way could be set onto the shaft and moved in the other direction. However, individual dimmers could be moved by hand in the opposite direction to the shaft. Channels on different colour shafts could move in different directions at the same time.

Chapter 2: What were the reasons for the invention of the Light Console?

The main inspiration for the Light Console, and indeed Colour Music, happened long before Fred Bentham came to work for Strand Electric. When he was about 12 years old, he would go and see films in the cheap matinees at his local cinema. At that time, most of the films were silent so an organ and player were used to play music in time to the moods and action of the film. Bentham would go just to see the organist at work. There was a fashion for colour mixing lights in the décor of Cinemas during the interludes. Lights were concealed around the screen and in the ceiling of the cinema, and the colours would slowly change, but not in time with the music being played.

This mixture of the organ and the changing colours left a big impression on him, as he built his own model theatre, using low voltage lamps, Meccano, and variable rheostats to play around with ideas. At the time, the lighting in the cinemas was considered part of the decoration; Bentham wanted it to become an art itself and came up with a concept of Colour Music. Bentham was by no means the first person to consider linking music with colours. It has been looked at for over two hundred years, but most of these ideas have not worked very well.

Fig. 7. Examples of Colour Music: a) On material, b) On a 3-Dimentional Object.

Beforehand, it was thought that it was possible to link each note of a scale, or a chord, to a colour. The problem with this is that it can be a very personal opinion. One person may see one colour and another person a different colour, for the same note. They are probably both right, as it is what the individual sees and it cannot be forced onto them. This is probably why the other attempts did not work. Bentham changed the lighting with the emotions and moods of the music, not with each note played, and the colours were not necessarily linked. He was also not the first person to play Colour Music, or to link with the organ idea. In 1895, A. Wallace Rimington demonstrated his “Colour Organ”, which accompanied a piano or an orchestra, with a play of colours on a screen. Major Adrian Bernard Klein introduced a “Colour Projector” in 1921, with a control that looks very close to an Organ. He also wrote a book called “Colour Music – The Art of Light” in 1926. Another attempt was the “Clavilux”, by Thomas Wilfred in 1919 - 1925, although it does not quite look like an organ. Bentham heard of these attempts, but dismissed them. In reference to Colour Music, he said, “There is no direct relationship between the music we hear and what we may expect to see.”[2]

Fig. 8. Rimington’s Colour Organ.

Fig. 9. Bernard Klein’s Colour Projector and control.

Fig. 10. Thomas Wilfred’s Clavilux.

Fred Bentham had quite a bit of interest in using Strand Electric to make a Light Console. It would take quite a bit of time to realise his dreams, but eventually the perfect opportunity was found to construct one, demonstrating the lighting equipment that Strand Electric sold. It was obviously not economical to show the lights under “normal”, theatrical conditions, as this would require a cast to be ready to perform a show at anytime someone came in to look at the equipment for sale. The Light Console could always be ready to show what each type of light could do, and give some ideas to people on how to use lights in a more interesting way.

Perhaps the first step to the first working Light Console was not the cinema organ itself; Bentham knew that an organ would work, but how would it control the dimmers? The answer was in another invention, the Magnetic Clutch by Moss Mansell, circa 1931. Essentially, the Magnetic Clutch is composed of two pairs of electromagnets. When electricity passes through an electromagnet, it acts as a magnet. When there is no electricity, it does not act as a magnet. They could therefore be used to grip onto a rotating wheel, and release, instantly at the flick of a switch. To put it simply, the clutches were used to replace the handles on the Grand Master, but the clever part was to use two clutches. One clutch raised the level of a dimmer; the other clutch lowered the level. All of this was possible on a shaft that was constantly rotating in the same direction.

Fig. 11. Two dimmers with Magnetic Clutches, on the same shaft.

Fig. 12. Diagram explanation of Clutches in Fig. 11.

Fig. 13. Diagram to show how the dimmer was moved by the Clutches.

This new invention effectively permitted remote control of a Grand Master. This was tried in the Covent Garden Opera House in 1934. However, the control was designed at short notice, and had many poor features. There was no motor to drive the dimmers, so two wheels under the control, one geared for slow fades, which are popular in Opera, and the other for faster fades, were turned as before. The channels could only be selected to move up, down, or stay in the same position. The Light Console could also be classed as a remote operating control for the Grand Master, but the way which you used the Light Console was revolutionary.

Fig. 14. Covent Garden Opera House’s control of 1934.

The choice that Bentham made to use an organ was influenced by the way that all of the controls were within reach of one operator. He made a further choice to utilise Compton Organ’s components and manufacturing techniques, manly because of the way they worked. Wurlitzer Organs used other methods of control, which would not have worked with the Magnetic Clutch. This is a classic example of what happens in theatre, technical advances are made for another industry, and the theatre can adopt them and use them to invent new things. Most importantly here, it combined remote control of the dimmers, with the ability to play the lighting. Bentham also had a distinct hatred for the Grand Master, which was often specified up to the 1950’s even though his Light Console was available.

There was originally no market for the Light Console, theatres were reasonably happy with their Grand Masters. They certainly would not require an upgrade so soon, or be able to afford the change. Bentham would have to create a market for it first. Therefore the Light Console might not have started off as well as it could have, if there had been a demand for one. It is quite possible that the Light Console was ahead of its time. Most importantly, the Light Console was actually designed for cinemas, not theatres. This is not surprising, as if it had not been for the demand for lighting from cinemas, Strand Electric would have collapsed before Bentham started to work for them. Most of the equipment Strand Electric produced in the 1930’s went into cinemas.

Chapter 3: How did the Light Console work?

Fig. 15. Light Console compared to a Grand Master, with Fred Bentham at the console.

As discussed in previous Chapters, the Light Console was loosely based on the Grand Master type of control. A variable speed motor replaced the main wheel, and Magnetic Clutches replaced the selection method of the channels. The Electromagnets were simply energised, and gripped onto the metal of a wheel on the shaft, and by a series of links, pulled the dimmer to and fro.

The Light Console used the same basics of operation as the Grand Master. The channels were selected, the channel direction was selected, and the speed set. The Light Console was direct action, any adjustment made to the channels on it would affect the lights on the stage. The difference of the Light Console was that many additional facilities were available, for the first time. Changing the position on a switch called a “Stopkey” made the channel selection, the direction of movement in the cue was chosen by pressing a “Master” key, and a pedal set the speed.

The stopkeys ran across the top of the Light Console, and selected the channels that would be changing in a cue. As with normal organs, these stopkeys were double touch, which in effect meant there were two switches in the space of one. When the stopkey was taken to first touch, which only took the weight of your finger, it would select the channel. If taken to second touch, which required pressure from your finger, it would isolate that channel from any others selected. From here, this channel’s level could be adjusted, or read from a dial. The second touch was momentary, so as you removed your finger, it would revert to first touch. When the channel was not selected, the level would not change, even if other channels in the same colour group did.

The stopkeys were coloured and the standard colours used were White Red, Blue, and Green, as they represented the colours in the Battens. The independent lights were spread over the colour groups by location, (i.e. Spot 1 on Red, Spot 2 on Blue, and so on) and not by the colour of the light produced. This might have been confusing, as the Grand Master had two extra, separate, shafts for these lights. The colours corresponded with the colours on a keyboard, which is known as a “Manual” on an organ. This is the point where the Light Console can be played. The keys were divided up according to what they did, and then organised in colour order. There were three types: Blackout/Dim, Raise/Dim, and Full-on/Raise. These keys were called the “Masters”, as they controlled all of the channels and were also double touch, so to use the first function, the finger was lightly pressed on the key. To obtain the second function, (after the slash) extra pressure was required. At first sight, it seems that some of the functions have been duplicated on different keys, but this is not the case.

The first key, Blackout/Dim, on first touch would operate a contactor at the dimmer, and the lights selected would instantly Blackout, until the key was released. On second touch, it would instantly Blackout the channels, then, run all of the selected dimmers down to zero. The next key, Raise/Dim, on first touch would raise the levels of the selected channels until the key was released. On second touch, it would dim them, until the key was released. This Master may have been flawed, as to get to the Dim function, you had to pass through the Raise function. This might mean that the dimmers would rise for split second before dimming. If the dimmers took a bit of time to react, it might not have been a problem. In theory it might have been noticeable when trying to adjust the levels of dim lights, or entire states, as changes in light are more apparent to the eye at low levels. The last key, Full-on/Raise, on first touch would operate a different contactor at the dimmer, and the channels selected would go instantly to full on, until the key was released. On second touch, selected channels would go instantly to full, and then the dimmers would be raised to full on.

Fig. 16. A two Manual Light Console in the Theatre Museum Store.

On larger Light Consoles, if the number of channels was over thirty-six, they were divided over three sets of Masters. There was the left Master, controlling one set of 36 channels, and a right Master, controlling the other set. In the middle of these, there were the Centre Masters, which controlled both the left and right Masters at the same time. When there were over 72 channels, a second manual was used, and so forth. The Light Console was able to control colour changers when fitted, without taking up extra space. The channel stopkeys also selected the colour changers. Then one of the black keys in the manual was pressed to change to the colour. There was also one pedal to each manual, which controlled the speed of the change.

The pedal of the Light Console was balanced, which meant that it stayed in place once set, it was not used like an accelerator in a vehicle. However, this seems to be the weakest part of the Light Console, in my opinion. The pedal, and therefore the speed, was not infinitely variable; it operated a series of switches, which selected the speed of the motor. On the smaller Light Consoles there were five speeds, on the larger ones there were seven speeds. The speed selected was indicated on the Light Console by a series of lights that would light up to the level selected. The range was from 3 to 40 seconds, a slow fade would have to be done in small steps, inching the levels around. Faster cues would have to use the contactors. I suspect that there were mechanical restrictions in the dimmers, which led to the limits imposed. If a Light Console was used today, with modern dimmers, with no moving parts, this limit would no longer be valid. A modification to the pedal, and this problem would be eliminated completely.

The feet were not left idle while operating the Light Console, and there were many functions available on “Toe Pistons”, some were even double touch. Although the Light Consoles varied, some of the functions available were: Dead Blackout/General Dim, Motor Stop (could be used to help with very slow fades, and rough presetting), and Reverse. Most of these tell their own story, but Reverse is interesting. It allowed channels of the same colour group, to move in the opposite direction to that of the Master key being pressed.

To use it, the toe piston was pressed, then the required channels were taken to second touch, then the toe piston was released. When the Master keys were pressed, the normally selected channels would move one way, and the specially selected ones would go the other. If the Raise/Dim key was pressed to first touch, the normal channels would raise their levels, but the Reversed channels would dim. To clear this function, the selected stopkeys would have to be turned off, and when they were used again, they worked normally. This would not have been possible on the Grand Master, and was very useful. However, it did mean that no other stopkeys could be taken to second touch, even if they had not been selected to reverse, so no levels could be read. Bentham must have spotted this, and added a “Reverse Sustainer” Toe Piston, which was used while pressing the desired stopkey to second touch. This is a good example of the occasionally complex operation.

There could be so many channels on the Light Console that it could become hard to select the channels that were going to move. This would have been particularly evident when the cues were quite close together. Therefore the Light Console had a form of presetting, but not in the same way that modern lighting control does it. The Light Console utilised some more of Compton’s equipment, this time in form of the “Group Memory Box”, as used in the real musical organs from 1929.

Fig. 17. Group Memory Box (actually from a later control, but would have looked similar).

It was a mechanical storage device, using many solenoids, which could be “programmed” to remember the selections of channel stops, but not the levels. To program it, the channels required were selected to first touch, and then a toe piston called “Setter” would be pressed and held while a “Combination Piston” was pressed. This would program the Combination Piston, which when required, was pressed and the stopkeys went to their programmed places. The Combination Pistons were located in the keyslips (this is the area below one manual) This feature was only available on the large Light Consoles, on the smaller ones, a “Hold” switch would allow the operator to set up the next selection of stopkeys while the current selection would remain active.

Fig. 18. The 1949 Palladium Light Console, showing the Combination Pistons under the manuals, and the foot controls. It controlled 152 dimmers and 80 colour changers.

The more channels the Light Console had, the more Combination Pistons were available. They worked in a way that could be directly linked to the binary storage system used today in digital technologies, such as computers. Any one Binary Digit is either “On” or “Off”, exactly like the stopkeys. This system pioneered the idea of memory control, with the later addition of the level of the lights; we arrive at the basic control available today.

Chapter 4: What was the Light Console like to use?

A Light Console operator, situated in the

ideal position, would always be able to look at the stage, and make amendments

to the levels if required, or leave them alone if it was okay. Fred Bentham

classed operators as artists in their own right, varying the lighting each

performance, with the action on stage. A modern argument here is that a lighting

designer designs the pictures of light on the stage, and the control

consistently replays them identically each time. If the operator modifies these

pictures then it becomes their design and not the lighting designer’s.

As the Light Console was designed to have one person controlling it, no button was out of reach, and the soft motion of the stopkeys meant that they could be selected with ease, and whole areas of stopkeys turned on or off with a swipe of a hand. The ergonomics of the Light Console were so well thought out that everything was easy to find and clearly labelled. Many original operators have reminisced about using a Light Console and most say it was pleasure to use.

The simple operation of the Light Console

is as follows:

Select

channels but putting their stopkeys to first touch.

To

have channels move in the opposite direction, press the “Reverse” Toe

Piston, and select channels with second touch.

Select

the speed of the cue by moving the pedal(s) to the required position.

Press

a Master key on a manual of required function to first or second touch as

appropriate.

When

the lights are at the required level, either release the Master key, or if

the lights have to be dropped off at different levels, de-select their

channel stopkeys.

Repeat

for the next cue.

This is a very simple guide, as some of the

advanced functions were more complex, but very simple to do once you got the

hang of it. Fred Bentham likened it to driving a car, it took a while to learn

how to use, but after time, it became second nature. As soon as a fault was

spotted with the lighting, the offending channels could be selected and be

modified without delay. This is a function that many modern controls lack, as

they do not have a fader to each channel. Something that was slightly harder

with the Light Console was the plotting session. After the states had been

created, it would take the operator a while to work out how the cue would

actually be controlled, and then make a note of it. This could have led to many

mistakes, and this problem would ultimately be solved with memory controls, as

all of the plotting was calculated and stored automatically.

One such plotting problem with the Light Console was that a state might be any combination of previous states. Not a problem visually, or in the way the Light Console worked or was being used, but it could be a problem in rehearsals. If the operator was required to jump around the cue list without going sequentially, the state brought up on stage could be wrong. This would mean that it took time for the operator to see what had happened in the last few cues so that the state could be recalled correctly. Memory control would remove this problem by storing all of the information about which lights were on, and at which level.

Fred Bentham wrote

“If it is a switching

or fast cue and the control is not a Preset type, do not ask for a large number

of existing channels to change to an entirely unrelated series.”[3]

I am unsure if he was referring to the Light Console with this statement or not,

but it could be important. Was this an additional weakness of the Light Console?

It could control a lot of channels, but if they could not be operated in quick

succession, then a show that needed lots of big changes might have found it

hard. The Combination Pistons would have helped with this, but only if they were

fitted. The memory controls would eliminate this problem, as there was no need

for channel selection.

Having said this, the Light Console had

many features that were lost when memory controls were designed, and are still

missing today. It is still hard to cue lighting that depends on a live flame and

cue on stage. For example, imagine that 3 candles have to be blown out one after

the other, and the state on stage must dim each time. Three cues are programmed

into the modern lighting control, and the “GO” button is pressed when each

is blown out. As is now standard practice, the Deputy Stage Manager (DSM) cues

the lighting operator. However, by the time the DSM has passed on the command

and the lighting operator has pressed “GO”, there is a delay.

Now imagine that one candle looks like it

has gone out but suddenly it relights, the DSM has already cued the operator,

and the “extinguish” cue has happened. The operator could decide to press

the “BACK” button, but has to put this past the DSM, and in the time it

takes for this to happen, the candle has been blown out. The Light Console, and

an operator on the ball, could cope with this problem without difficulty. The

state or special lanterns are selected, and the cue is played. If a candle

relights, a quick change of pressure to change the touch, and the lights come

back on, ready to go out again. This would only be possible if the operators

could make their own decisions.

The role of the DSM is very important, they

make all of the decisions when the show is running. This was not quite the

practice many years ago, and Light Console operators could make their own

decisions, and change the lighting when they thought it was right to. The modern

way of being cued is basically fine until something goes wrong, either a cue is

missed, jumped or something goes wrong with the lighting. The DSM may not know

what can be done, and it is here that I suggest that the lighting operator of

today should take a bit more control of the lighting. After all, theatre is all

about live performance, some good, and some not so good, so why should the

lighting stay the same regardless? Lighting can really add something to a dull

performance or make a good one even better.

The Light Console was more convenient than any of the other contemporary controls to operate. Yet, it could also be harder to use, as it was unlike the controls people were used to. I have discovered that quite a bit of pressure was required to keep the Master keys at first touch, even more so at second. On longer cues, fatigue sets in and the possibility of accidentally taking the keys to the wrong touch increases. Many modern lighting controls specifically designed for Rock and Roll and music events, have many features that are more playable than other modern controls. Their operation can be linked to the Light Console, but no lighting control today offers operation via a musical keyboard.

Chapter 5: Why did the Light Console seem to disappear so suddenly, along with most of its ideas?

The Light Console seems to have had a very short production life. They lasted well in the theatres that had them, but there were only 17 Light Consoles ever made. The Light Console was partly designed for the Batten style of lighting, but when the style changed to lots of lanterns, in various locations, the Light Console’s method of grouping may not have been suitable. I stated earlier that the Light Console might have been ahead of its time; it is possible that when the time for it came along, people wanted other things from a lighting control.

One of these requirements was presetting. There was a demand for presets since the 1930’s, but the mechanical technology of the time would not allow it. When more solid-state (solid-state means there are no moving parts, it is all electronic) dimmers became available, presetting was possible. The idea of presetting is that the next state can be set up before it is required, and then one fader can be used to operate the cue. The major advantage of this was that the level of the lights could also be set before the cue took place, a feature that was limited on the Light Console. It was possible to hold the Blackout contactors in, and by using many other controls, set the level of the lights roughly by looking at the four dials. However, by using the contactors, the only way to move into the state just set up was instantly, therefore, it was probably not very useful. The reason for the limited presetting is that Fred Bentham wanted the operator to see the actual lighting state on the stage, and not via the dials on the Light Console.

The drawback of presetting is that the lighting installations were getting so big, that there could be well over 200 channels. This means that it would be very hard to have one operator set 200 or more levels on the next preset, particularly if the cues were close together. The simplest solution would be to employ a second operator to load the presets, but that was a step backwards. Another was to have more presets, normally 3 to 4, but sometimes up to 10. The problem with more presets would have been the actual size of the control, as all of the channels would have to be included on each preset. For the example above, it could mean 2,000 faders, and with that amount, it would be hard to find space for the control.

A rival manufacturer to Strand Electric, Siemens, tried to miniaturise the size of the preset faders. This was quite a good idea in principle, but there were many problems. It was very hard change the levels live during the scene, it was also very hard to see levels when plotting, and the grounds for setting the wrong faders must have been higher. Despite the miniaturisation, it still required quite a large space. You could put a large control in the auditorium, but it would take up too many seats, so could it be put somewhere else in the theatre?

I believe that this is the origin of the control box. As stage lighting technology advanced; it could move itself around the theatre a bit. The start of this shake up would probably be due to the follow spots no longer needing to be noisy Arc. Before, they were separated from the audience in a room of their own, at the back of the theatre behind glass. If the theatre had silent electric lamps, the follow spots could go outside into the auditorium, at the sides of the Balcony or Gallery, and not take up too much space. This meant that the room where the follow spots were could house the lighting control. It seems an ideal location, as a clear view of the stage would be available, because the follow spots could light it before. The only disadvantage of this was that the stage could be seen, but not heard, so it might have been a case of two steps forward and one back. One of the important ideas of the Light Console was that you could see and hear the stage, this could also be the point when the role of the DSM changed to cue the lighting as well. Even with today’s modern video and audio links, it is still preferable to have the control within eye and ear range of the stage.

With the advent of microprocessors and the computer, it would not take long for the theatre to adopt the technology, to store all of the information of the states, and times of the cues. The advantages of computer controls over presets are that the states can be played back instantly, in any order, and there are no levels to set during the show. The term for the levels in a state would be called a memory, but was the same principle as a preset. As all of the levels were stored automatically, there was no need to write a plot for the lighting, therefore saving time. This new technology must have been exciting to designers, as suddenly, the room for operator error was reduced dramatically.

As mentioned before, a state on the Light Console might be a combination of previous states. The memory controls removed this problem by recording every channel’s intensity, even if it was off. This entire recording of the state would also lead to the other advantage that the levels would always be right, each time the show was performed. It could also mean that the use of faders was not needed during playback, and some controls eventually used a keypad for most of the data entry and operation.

The theory of the keypad is that it’s easier to find your way around ten keys (0-9) plus operation keys (the “at level” button for example) than it was to remember the location of all of the faders. Even Fred Bentham was led to write “The truth is that with a memory system, we should not use positional faders at all.”[4]. This statement is very interesting, as he liked the idea of having instant access to the lighting channels, which both faders and the Light Console gave. It takes slightly longer to press buttons in sequence than it does to move a fader. However, with 200 or so faders, it might take the same amount of time to find the fader first. This method of data entry by keypad is still with us today.

The ideas of keypad entry, and screen displays are fantastic, but I felt that they instantly made operators and to some extent, the lighting designers become more interested in the numbers on the screen rather than the lighting on the stage. I studied how a lighting designer composed her states recently. She would ask to bring up some lights slowly until she thought they looked right. She then asked for their intensities, which she did not write down, and moved onto the next set of lights. I questioned her about this after the plotting session, and she explained that she wanted to know that their intensities matched what she was seeing on the stage. Therefore, she was interested in both the numbers on the screen and the lighting on the stage; and sometimes paused to add Neutral Density gel to the lights, so that they could be full on, but the light produced was dimmer. This example proved me wrong, and I was impressed that she was using the information available to further balance her lighting states.

In the 1950’s and 1960’s, Television was starting to take off, particularly when the BBC was about to have a rival with the launch of Independent Television. The BBC wanted to have a new form of lighting control, and asked Strand Electric to come up with a control for the new Thyristor, or Silicon Controlled Rectifier dimmers (the base of most modern dimmers). They came up with the system C/AE (Console/All – Electric) that was based on the Light Console, but had more presetting features, and no keyboards. It was not a computer memory control, but it ensured that Strand Electric would continue to lead the market in lighting control for a little while longer.

Fig. 19. A System C/AE Control.

Fig. 20. The Prototype Q-File.

Fig. 21. The DDM Control.

The costs of looking into all of this modern computer and solid-state

technology made Strand Electric run into financial difficulties. When the Rank

Organisation bought them in 1968, it must have been a mixed blessing. The

obvious advantage was that there was more money available, which ultimately led

to the development of computer-based controls such as IDM (Instant Dimmer

Memory), and DDM (Digital Dimmer Memory). Both controls were partly designed by

Fred Bentham, but the later was his last with the company, and ironically, it

used rockers to select channels, which directly compared to the stopkeys on the

Light Console. The DDM and Q-File represented memory control in 1970, and ever

since, the development of new controls have become faster. One control was made

by Rank Strand in direct competition with Q-File,

called MMS. MMS stood for Modular Memory System, and controls could be

customised to the particular requirements of the client my adding or removing

features

The disadvantage of the take over was

that the management of the company now called Rank Strand seemed to change every

few months. This annoyed Bentham quite a bit and he eventually left Rank Strand.

This ultimately meant that Rank Strand had no major force directing it into

researching and developing their systems to compete with all of the rivals, and

subsequently no major advances were made. Other companies started to lead the

design, and with the advent of the moving lights, controls are getting very

complicated indeed.

Perhaps the biggest downfall was that

the Light Console was Fred Bentham’s individual solution to his own problem of

“playing” Colour Music, but this wasn’t really a problem for the rest of

the theatre industry. If he had asked the industry what they wanted from a

control, in addition to working on his own wonderful idea, the Light Console

might have been a huge success and we might be using their direct descendants

today.

The development of stage lighting has

taken a long time, and was often totally reliant on technology advances outside

of the theatre. It has been fascinating to see how much work went into the

design of the Light Console and other parts of stage lighting, and how much we

take for granted today. Once developed, the types of lantern have stayed the

same for half a century or so now, it is the control side that has been refined

more, and giant leaps seem to be made today, but is the theatre any better for

it? I believe that the audience would not notice what lighting control was being

used, but the people working in the theatre would be aware if a straightforward

or problematic control was being used.

The Light Console was ahead of its

time, with its innovation of remote control, but relied on an old technology to

work, which had major limiting effects, and meant it could not compete with the

later developments in electronics and computing. Other limiting factors to its

popularity included the lack of presets, and poor control of timing. I strongly

believe that the basic functions of the Light Console could still be used today.

It could be particularly useful in venues where the lighting has to be

“busked” or made up on the spot.

Fred

Bentham died on the 10th of May 2001. Although there were so few

Light Consoles made, his legacy of remote control will live on forever.

© Robert Oxlade 2007

[1] Fred Bentham, Sixty Years of Light Work – An Autobiography, 2001, Page 148

[2] Page 21, “Organo Ad Libitum, Or Prometheus Not Yet Unbound”, in TABS, Vol. 35, No. 3.

[3] Fred Bentham, The Art of Stage Lighting. London: Pitman, 1976. p 192.

[4] Fred Bentham, The Art of Stage Lighting. London: Pitman, 1976. p 162.

Roy Castle, the late entertainer, recalls working in the Victoria Theatre in Burnley, circa 1947, and talks about a Dead Black Out:

“DBO means Dead Black Out and leaves the audience in no doubt that this is the end of the sketch. I was in charge of giving the electrician his cue to throw the switches. He was a short, thin-set individual with steel-rimmed goldfish-bowl glasses and in need of a shave. He was wearing thick rubber gloves as he prepared to throw two ancient mains levers. He took great pains to clear the way behind him which had me quite bewildered. We reached the end of the sketch and I gave him the cue. He threw the switches and there was an almighty flash. As my eyes gradually returned to their normal duty, I saw no sign of our electrician. A groan from the back wall attracted my attention and there he was in a creepled hump. He picked himself up, staggered back to his switchboard and flashed the switches back on. He was not thrown quite so far this time. I couldn’t believe it, my chin was on the floor.

'Phew that was close. It really threw you back that time.’

He replied with a thick Geordie accent. `Why man, it always does that!’

There were three more DBOs in the first half – and no safety net!”

Page 22 – 23, Now and Then, An Autobiography. London: Macmillan General Books, 1995.

Fig. 1. Page 180, Theatre Lighting in the Age of Gas. London: The Society for Theatre Research, 1978.

Fig. 2. Page 119, Practical Stagecraft for Amateurs. London: George G. Harrap & Co, 1936.

Fig. 3. Page 111, Stage Lighting. London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd, 1950.

Fig. 4. Page 382, Sixty Years of Light Work - an Autobiography. Hertfordshire: Entertainment Technology Press Ltd, 2001.

Fig. 5. Diagram drawn on AutoCAD LT by the author.

Fig. 6. Page 86, Stage Lighting. Ibid.

Fig. 7. a) Page 121, Sixty Years of Light Work - an Autobiography. Ibid.

b) Page 21, "Organo Ad Libitum Or Prometheus Not Yet Unbound" in TABS, Vol. 35. No. 3., Autumn 1977.

Fig. 8. www.adh.brighton.ac.uk/schoolofdesign/MA.COURSE/LColour01.html

Fig. 9. Page 209, The Oxford Companion to Music. 9th Ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1955.

Fig. 10. Page 209, The Oxford Companion to Music. 9th Ed. Ibid.

Fig. 11. Page 113, Stage Lighting. Ibid.

Fig. 12. Diagram drawn on AutoCAD LT by the author.

Fig. 13. Diagram drawn on AutoCAD LT by the author.

Fig. 14. Page 114, Stage Lighting. Ibid.

Fig. 15. Page 111, Sixty Years of Light Work - An Autobiography. Ibid.

Fig. 16. Photo taken by the author at the Theatre Museum Store, Battersea, 2001.

Fig. 17. Photo taken by the author at the Theatre Museum Store, Battersea, 2001.

Fig. 18. Page 131, Stage Lighting. Ibid.

Fig. 19. Page 244, Sixty Years of Light Work - An Autobiography. Ibid.

Fig. 20. Page 94, The ABC of Stage Lighting. London: A & C Black, 1992.

Fig. 21. Page 33, The ABC of Stage Lighting. Ibid.

Books

| Banham, Martin, ed. | The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | Stage Lighting. London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons Ltd, 1950. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | The Art of Stage Lighting. 2nd Ed. London: Pitman, 1976. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | Sixty Years of Light Work. London: Strand Lighting Ltd, 1992. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | Sixty Years of Light Work - an Autobiography. Hertfordshire: Entertainment Technology Press Ltd, 2001. |

| Bergman, Gösta. M. | Lighting in Theatre. Sweden: Almqvist & Wiksell International, 1977. |

| Brandon-Thomas, Jevan. | Practical Stagecraft for Amateurs. London: George G.Harrap & Co, 1936. |

| Castle, Roy. | Now and Then, An Autobiography. London: Macmillan General Books, 1995. |

| Corry, Percy. | Lighting the Stage. 2nd Ed. London: Sir Issac Pitman and Sons Ltd., 1958. |

| Cunningham, Glen. | Stage Lighting Revealed. Cincinnati, Ohio, USA: Betterway Books, 1993. |

| Fitt, Brian & Thornley, Joe. | Lighting Technology. Oxford: Focal Press, 1997. |

| Griffiths, Trevor. R. | Stagecraft. London: Quarto Publishing Ltd, 1982. |

| Hindley, Geoffrey, ed. | Larousse Encyclopaedia of Music. London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd, 1971. |

| Hoggett, Chris. | Stage Crafts. London: A & C Black, 1975. |

| Keller, Max. | Light Fantastic. Munich/London/New York: Prestel Verlag, 1999. |

| McCandless, Stanley. | A Method of Lighting the Stage. 4th Ed. New York: Theatre Arts Books, 1958. |

| Mobsby, Nick. | Lighting Systems for TV Studios. Hertfordshire: Entertainment Technology Press Ltd, 2001. |

| Morgan, Nigel. H. | Stage Lighting for Theatre Designers. London: The Herbert Press Ltd, 1995. |

| Pilbrow, Richard. | Stage Lighting. 2nd Ed, 3rd Impression. London: Cassell Ltd, 1985. |

| Rees, Terence. | Theatre Lighting in the Age of Gas. London: The Society for Theatre Research, 1978. |

| Reid, Francis. | The Stage Lighting Handbook. 2nd Ed. London: A. & C Black, 1982. |

| Reid, Francis. | Discovering Stage Lighting. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Focal Press, 1998. |

| Reid, Francis. | The ABC of Stage Lighting. London: A & C Black, 1992. |

| Ridge, C. Harold. | Stage Lighting. Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons Ltd., 1928. |

| Sandström, Ulf. | Stage Lighting Controls. Oxford: Focal Press, 1997. |

| Scholes, Percy.A. | The Oxford Companion to Music. 5th Ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1942. |

| Scholes, Percy.A. | The Oxford Companion to Music. 9th Ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1955. |

| Walters, Graham. | Stage Lighting Step By Step. London: A & C Black, 1997. |

| Vasey, John. | Concert Sound And Lighting Systems. London: Focal Press, 1989. |

Magazines / Journals (Arranged by Date/Issue)

TABS

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Towards An Ideal Lighting Control" in TABS, Vol.23. No.4., December 1965, pp. 16-23. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Ideals And Realism In Lighting Control (I)" in TABS, Vol.24. No.1., March 1966, pp. 13-18. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Ideals And Realism In Lighting Control (II)" in TABS, Vol.24. No.3., September 1966, pp. 18-21. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Saturday Night And Sunday Morning At The London Palladium" in TABS, Vol.24. No.4., December 1966, pp. 25-29. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "At Last Or No Longer A Luxury" in TABS, Vol.25. No.2., June 1967, pp. 15-20. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Light And Lighting" in TABS, Vol.27. No.1., March 1969, pp. 20-28. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Lighting The Hardware Way" in TABS, Vol.27. No.2., June 1969, pp. 26-31. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Only Presets Will Do" in TABS, Vol.29. No.1., March 1971, pp. 14-15. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Theatre Lighting 2000: A Darkling View" in TABS, Vol.29. No.1., June 1971, pp. 49-55. |

| Southon, Laurence. | "Piano Keyboard Modification For SP80" in TABS, Vol.31. No.4., December 1973, pp. 186-187. |

| Dawe, Frank. | "Lighting On The Move" in TABS, Vol.32. No.2., Autumn 1974, pp. 8-9. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Organo Ad Libitum Or Prometheus Not Yet Unbound" in TABS, Vol. 35. No. 3., Autumn 1977, pp. 19-21. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Famous Strand Jobs Of The Past, Or I Was There!" in TABS, Vol.38. No.1., June 1981, pp. 20-22. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Famous Strand Jobs Of The Past Or I Was There" in TABS, Vol.39. No.1., May 1981, pp. 20-22. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "I Was There!" in TABS, Vol.41. No.1., March 1984, pp. 21-23. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "I Was There!" in TABS, Vol.43. No.1., Feb 1986, pp. 20-22. |

CUE

| Baldwin, Chris. | "Symphony In Red" in CUE, September/October 1979, pp. 18-19. |

| Corry, Percy. | "Basic Wood And Technological Trees" in CUE, November/December 1980, pp. 6-7. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Replayed With Interest" in CUE, Nov/Dec 1980, p. 27. |

| Plinge, Walter. | "Between Cues, The thoughts of Walter Plinge" in CUE, May/June 1981, p. 32. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "A Colour Music Hall" in CUE, May/June 1982, pp. 15-18. |

| Plinge, Walter. | "Between Cues, The thoughts of Walter Plinge" in CUE, May/June 1983, p. 24. |

| Reid, Francis. | "Frederick Bentham, First Fellow Of The ABTT" in CUE, Jan/Feb 1984, p. 12. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "Odd Enough Or Down In Ringmer Some One Stirred" in CUE, July/August 1984, pp. 13-15. |

| Reid, Francis. | "Control Board Alphabet, an A B C for 1987" in CUE, Jan/Feb to Nov/December 1987. |

| Bentham, Frederick. | "A Chromatic Diversion In C Or D" in CUE, March/April 1988, pp. 10-14. |

FOCUS

| Laws, Jim. | "Feature" in Focus, May 1994, pp. 3-5. |

| Pilbrow, Richard. | "Frederick Bentham (1911 - 2001)" in Focus, June/July 2001, pp. 3-8. |

| Williams, Julian. | "FPB And His Light Console, And Their Final Cue." in Focus, June/July 2001, pp. 9-10. |

Other Items

| Burgess, Francis. | "The Organ at Southampton Guildhall" Reprinted from The Organ, July 1937. |

| Collier, Andy. | "Fred Bentham 1911 - 2001" in ABTT Update, No.38, June 2001, p. 6. |

| Craig, Edward Gordon. | "Colourific Music And Its Early Protagonists" in The Mask, Volume Thirteen, 1927, pp. 158-160. Reissued |

| Morley, Mark. | A Guide To Theatre Lanterns. Ringwood: AJS Theatre Lighting and Stage Supplies Ltd., October 1990 Revised Edition. |

| Strand Electric. | Lighting Control. London: Strand Electric & Engineering Co., Ltd. Circa 1939. |

| Strand Electric. | Light Console Manual. London: Strand Electric & Engineering Co., Ltd., Circa 1940. |

Web Pages

| "The Association of British Theatre Technicians" | Accessed 19th November 2001 | www.abtt.org.uk |

| "The Association of Lighting Designers" | Accessed 19th November 2001 | www.ald.org.uk |

| "Rhythmic Light" | Accessed 13th January 2002 | www.rhythmiclight.com |

| "The Stage" | Accessed 13th January 2002 | www.thestage.co.uk |

| "Joost Rekveld Files" | Accessed 5th March 2002 | www.lumen.nu/rekveld/files/newart.html |

| "Rimington's Colour Organ" | Accessed 5th March 2002 | www.adh.brighton.ac.uk/schoolofdesign/MA.COURSE/LColour01.html |

| "Thomas Wilfred's Clavilux" | Accessed 5th March 2002 | www.gis.net/~scatt/clavilux/clavilux.html |

| "The Strand Archive" | Accessed 6th March 2002 | www.strandarchive.co.uk |