Proud of Balochistan

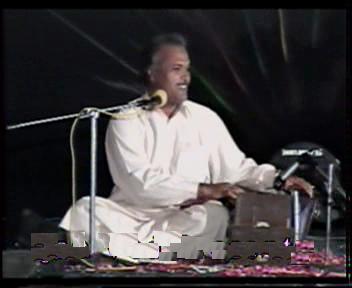

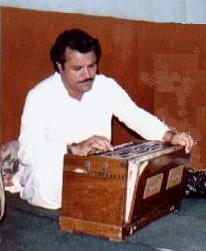

Noor Muhammad 'Nooral'

Singer Noor Mohammed Nooral, the most popular modern Balochi singer, has helped to rejuvenate the artistic heritage of his people.

He has brought Balochi poetry to the masses, reviving

the link between Balochi music and literature. He has breathed fresh life

into classical Balochi poetry and folk songs by presenting them in a new

way. He has helped to rejuvenate the artistic heritage of his people,

by giving a boost to poetry writing and encouraging cultural research.

Now, he has also taken up the task of projecting Balochi culture on a

wider scale. A trendsetter in many respects, Noor Mohammed Nooral is the

most popular modern Balochi singer.

A part from his contribution to the cause of culture, Nooral has also

played as important political role. In the late '70s and early '80s, the

political vacuum in the province was filled by the Baloch Students Organization

(BSO). In the absence of a towering personality to draw in the crowds,

the BSO employed a different technique to attract supporters. It began

to hold a series of Aashoobi Diwans, or revolutionary musical congregations,

where Nooral was the main attraction. His political songs were way a head

of common slogan-like songs doing the rounds at the time and were so popular

that even wedding ceremonies where Nooral performed became charged with

political electricity.

When Nooral first appeared on the Balochi music scene, it was flooded with pop and disco music. Imitations of Indian Filmi tunes, with facile tukbandi written by street poets with no literary talent, were also extremely popular, At the time, most political poetry that was set on music was either overly dramatic or superficial. Nooral chose to defy these trends and instead, opted for the work of well-respected and recognized poets'. The music to which he set these verses, too, was sober and melodious.

Nooral's decision to break away from the dictates of the market was discouraged by most of hiscontemporaries, who warned him that the popular demand was for catch pop numbers and discotunes. He responded by saying that while others might be content with the applause of their audience, he was singing for tomorrow. The doomsday predictions of his contemporaries were proved wrong, however, for Nooral did not have to wait long to taste success. His first studio-recorded cassette was an instant hit, and forever changed the face of Balochi music.

Nooral's astounding success proves that the "public" longs for quality entertainment. For instance, a rikshaw driver from lyari says that even though he does not understand' the poetry, the music is so melodious and effective that he feels it is the Balochi cassette he has even heard. Even though it is the public that is always blamed for its "bad taste", in fact, it is commercial-minded producer, themselves devoid of any kind of artistic sensibility, who promote low-quality music with the aim of making easy money.

Nooral's astounding success proves that the "public" longs for quality entertainment. For instance, a rikshaw driver from lyari says that even though he does not understand' the poetry, the music is so melodious and effective that he feels it is the Balochi cassette he has even heard. Even though it is the public that is always blamed for its "bad taste", in fact, it is commercial-minded producer, themselves devoid of any kind of artistic sensibility, who promote low-quality music with the aim of making easy money.

Nooral's success was not an over night miracle, however. Behind the instant popularity of his debut recording lies the formidable legacy of singers like Wali Muhammad Baloch who were undaunted by their political environment and recorded cassettes with serious music and poetry of high literary merit. But undoubtedly, the greater portion of his musical achievements can be attributed to his own long years of dedication.

Nooral's almost instant success did not go to his head; however. Realizing that he lacked a formal musical education, he began to search for a teacher. One day, walking out of Utad Beeday Khan's club, he ran into his earliest teacher, Ustad Umar, whose club had been disbanded. The Ustad invited Nooral to work with him, now that his club had been re-opened. Having found a teacher, Nooral embarked upon a rigorous regimen of training. He recalls that he sometimes sat from afternoon to evening, doing his riaz in a hot room with a roof made of asbestos sheets. During these exercises, he usually turned off the fan because its noise disturbed his concentration. Nooral also religiously attended Ustad Umer's evening lectures on different ragas and other aspects of music. Accompanied by practical demonstrations, these sessions went on until late into the night. In the early '70s, Nooral went to work in Dubai. Here, he met up with two music-loving brothers who have home been a kind of informal music club. Regular visitors to this gathering included Jagjit Sing, subsequently of the Jagjit-Chitraduo, who had not yet become famous. During his stay in the Gulf, Nooral continued to receive guidance from his teacher through detailed letters and audiocassette recordings.

Initially, Nooral sang Ustad ghazals at various gatherings all over the United Arab Emirates. In the early '80s, however, he was drawn back to Balochi music by the members of a social organization, Baloch Kumak-kar, with whom he also began to do social work. It was that the Nooral decided to quit Urdu and take up Balochi singing permanently. "It was a period of popular and disco music at home. "Nooral recalls, "but it did not influence me because I was so far away from it all." Soon thereafter, audiocassettes containing selections from Nooral's performance in the Gulf started appearing in the Pakistani market.

It was during a visit home in 1988, however, that Nooral recorded his first cassette in a studio. Following its massive success, the market was flooded with Nooral's cassettes. But the majority of these were bootleg Mehfil recordings, for which he did not receive any payment. Dealers were so keen to cash in on his popularity that one of them even released cassette titled Rafique OK in Nooral's style without the consent of the singer, who is one of Lyari's most popular stage artists. This tape was recorded at a wedding where Mr. OK, like other junior singers, sang several of Nooral's songs.

To date, Nooral has done eight studio- recorded cassettes. Of these, the most commercially successful is Ladoongay, a collection of wedding songs. In this album, Nooral sings traditional ditties that were rapidly being forgotten by the younger Baloch generation. He collected these songs from old women and rendered them in an up-beat tempo, accompanied by modern musical instruments. The popularity of this cassette is obvious from the fact that young Baloch girls-especially those from Karachi, who had become accustomed to singing Urdu wedding songs-have now turned to the Ladoongay numbers of their elders.

Nooral's singing has managed to revive a part of Baloch cultural heritage, giving new life to traditional songs, which were rarely heard. Another example of this kind of effort is the case of classical Baloch love stories which are preserved in long verses. These poems are still performed by traditional singers of Balochistan, called Pahalwans, in the classical style. But their archaic and difficult tune, combined with the obsolete diction of the verses, had made them almost unintelligible to the younger generation. Nooral recorded a few of these songs, especially poems about the most popular and mystical romantic couple, Hani and Sheh Mureed. Setting these old poems to new tunes, he breathed a new soul into their verses.

To unearth classical poetry Nooral has had to carry out

painstaking research. For example, he found seven different versions of

the legendary lovers, Keyya and Sadu's 'teetanali' from different parts

of Balochistan. Putting all of these together, he selected common themes

among them, and compiled eight different versions of the legend, which

he then recorded.

Sometimes, Nooral's research methods are more arduous, and quite unusual.

A word, 'kareba' appeared in one of his song. The karaba is particular

date, as well as the tree on which it grows. A gemstone, popular with

Baloch woman who traditionally adorned their jewellery with it, is also

known by this name. But this entire connotation did not make sense in

the context of Nooral's sons. He asked many Baloch elders about other

possible meanings for the word, but came up with nothing.

Not be daunted by his apparent failure, Nooral involved his listeners in this search. At a function held in Muscat, he put his query to the audience. The very next day, people started visiting or calling with various suggestions, none of which were satisfactory. Still more suggestions poured in through letters sent to Nooral or published in the monthly, Balochi.

After three years, an old man contacted Nooral, and finally

gave him the answer. This old man, now a permanent resident of Oman, hailed

originally from Shehran, a small town in Iranian Balochistan. Near the

town of Shehran flows a stream, on the banks of which stand 'karaba' date

trees. Resident of the area also calls this brook karaba. The old man

revealed that the poet of the verse under discussion belonged to the same

town. It seems that the word, karaba, refers to that stream, for the poet

claimed to have bathed his head in it.

Deeply appreciating the spirit of research revived by Nooral, the old

man informed the singer that it had now become a favorite pastime for

Baloch people in their gathering to discuss words that are no longer in

use, and try to find their meaning. Baloch women, especially those from

Iranian Balochistan, takes more interest in this search, add Nooral.

Owing the deep-rooted conservatism of Baloch society, Baloch women are

still not free to take part in musical activities, Nooral says with indignation.

Consequently, there is a dearth of female artists who can sing in Balochi.

It is for this reason that Nooral was compelled to record Ladoongay in

his own voice, even through female vocalist would have been more appropriate

for wedding songs.

Similarly, Nooral has collected a good number of 'chachs',

or riddles, which he would like to record with the accompaniment of music

so that they may be preserved. "I have been looking for a suitable

voice for them," he says, "but now I will record them in my

daughter's voice."

His admires believe that Nooral's contribution to Balochi music and culture

can be compared to that of an institution. But he has a few critics, too,

who accuse him of distorting Balochi music. They claim that Nooral's singing

is based largely on Indian ragas, while classical Balochi music is totally

different.

Nooral agrees with such critics, adding that Balochi is in fact closer to Arabic, Kurdish and Sudanese music. But, he says, "time brings changes into every thing and Balochi music is no exception." Nooral also point out that the modern Baloch poet has almost abandoned traditional forms of Balochi poetry and is mostly writing gazals, a genre borrowed from Persian literature, albeit with a new diction and modern metaphors. "So now can this new poetry be sung in the old way?" he asks.

"Every age has its own requirements, and music also has to go through the process of evolution, which requires adaptation," argues Nooral. He illustrates his point by mentioning the banjo, which was originally a Japanese instrument. After some changes made by the genius instrumentalist Bilawal Belgium, the banjo has now been incorporated into Balochi music. In fact, it has become such an integral part of Balochi music that someone unfamiliar with its background could not be blamed for thinking it is an authentic Balochi instrument.

The earlier part of Nooral's career saw him working in the Gulf, making sporadic visit to Pakistan to do recordings and give performances. Unable to balance both worlds indefinitely, Nooral has now returned to Pakistan and taken up singing full-time. He has also set up an organization, the Baloch Musical and Cultural welfare Society (BMCWS), which has held one function already and has planned several they for the future. Explaining the need for its establishment, Nooral laments the apathy of government institutions like Quetta TV and Radio, and the Balochistan Academy, which are meant to promote Balochi culture. "Quetta Radio receives a grant of five lakh rupees annually," Nooral reveals, " of which fifty thousand rupees are spent mostly on non-creative works, one-and a half lakhs are embezzled, and three lakhs are return to Islamabad." Given the incompetence of thje authorities, Nooral believes it is up to Baloch artists themselves for the preservation and promotion of their culture. The BMCWS is at present a one-man organization, Nooral dominates its decision making, and work without a proper team. Can one man, whatever his talents or reputation, take on a gigantic task, the likes of which has defeated even the mammoth governmental machinery? Nooral agrees with the critics who accuse him of distorting Balochi music. But, he adds, "time brings changes into every thing and Balochi music is no exception."