Domine Deus Sabaoth

Contents

Introduction and Motivation

This paper was provoked by the following posting [slightly edited, as presented

here] made to my email list:

"I am interested what you and others

at this list think regarding the following biblical dilemma, with which

I have been wrestling, off and on, since I was about sixteen years age.

How can one reconcile the belief that

the whole of scripture is in all its parts inspired by God and inerrant

(at least as far as the spiritual truths therein contained), with the fact

that some of the books of the Old Testament are merely a bloody account

of the profane history of the hebrew tribes and the brutal subjugation

by them of the aboriginal peoples of Palestine, which brutalities are often

ascribed

to God Himself?

God supposedly ordered them to slaughter

whole towns [e.g. Jericho -ed], to kill the women and children and

animals, to rip the unborn babies out of their wombs, and then to rape

some of the virgins, and offer the rest up to God. I have asked several

clergy this question, over the years.

-

A bishop in Rome told me in 1973 that God ordered

no such things, that the Jews did these things themselves on their own

initiative, ascribing them to God in order to justify their unjust actions.

This would mean that the texts of those books have been altered by the

scribes already a long time ago, which is plausible.

-

Here in Holland, I have asked four priests what they

think:

-

one said simply to not read those passages,

-

the other three indignantly told me that I was an

anti-semite,

even for asking such a question!

I am less bothered by the acts of God done to save

the Jews from Pharaoh and his armies (though what the Book of Exodus describes

goes far beyond the duty of any God to help anyone, even the Jews!) than

I am bothered by the totally senseless, utterly cruel and thoroughly unjustifiable

deeds described in other books of the Old Testament:

-

the orders from God to wipe

out the native peoples of Palestine, for example;

-

or the story of Israel's slaughtering

all the women and children of the tribe of Benjamin and then Israel's kidnapping

the virgins of another tribe so that the Benjaminite men would have wives

and continue to reproduce [Jdgs 19-21].

-

Or the supposedly divine law to kill

a witch [Ex 22:18, Deut 13:1-5].

-

Or the very unedifying story of the daughter in law

disguised

as a whore so that she might have sex with her father in law

[Gen

38:6-26].

How can any of this be remotely inspired by a just,

good and holy God, and portrayed as spiritually beneficious for Christians

of today? The Church, by not reading most of these stories in Her Liturgy

of the Mass, shows her disapproval or at least embarrassment at these Old

Testament stories, in spite of Her teachings on inspiration and inerrancy.

I can understand why God would temporarily choose

a particular people - the Jews - for a particular purpose. But that choice

did not have to mean - and in my conviction could not have meant - that

God wished the Jews to treat the non-Jews worse than beasts.

I think that the God described in some of the

most primitive parts of the Old Testament is not the God which we believe

in: the Holy Trinity, but rather, the tribal

war god of the Hebrew tribes. The early Hebrews had more than one god,

and worshipped their gods in much the same way as the non-Hebrews. Many

traces are to be found of this in the primitive Old Testament writings:

references to household gods [e.g. Gen 31:34],

amulets and fertility ceremonies. In other texts, there is an amalgamated

god.

It seems to me that there is in the Old Testament

a gradual development from primitive worship of a devil like tribal war

god to a God of All Nations, who will come in the flesh as the

Messiah; but how can one consider some books, such as Joshua, to be

religious as all, let alone inspired? I know of heathen writings which

seem more divinely inspired. The later Old Testament books, such as the

Wisdom books, are indeed inspired and useful: though Ecclesiastes is

an odd one with its eat, drink and be merry for tomorrow we die like the

animals! I sometimes read this to cheer myself up.

It is not my experience that the Jews of either

biblical times or of today were or are any better or worse than other peoples

on the face of the earth at the time in which they have lived. The discussion

on the Old Testament is not at all about the Jews. That is what the three

Dutch priests on three different occasions did not understand when I asked

them what they thought about the Old Testament; and which is why they called

me an 'anti-semite' just for

daring to ask them! The discussion actually is

about God: what he is truly like; and about the Church: what She actually

believes regarding those books and passages in the Old Testament; and what

minimum She demands of us to believe.

I doubt whether the Church has reflected upon

the divinely ordered atrocities and the many divinely prescribed death

sentences of the Old Testament at all; She has been too afraid to reflect

upon them and therefore probably has no real view on them yet, which is

why nobody can come up with a satisfying answer.

This is one of the biggest problems within the

Church: to avoid an issue and to forbid one to ask questions is no solution,

but serves only to postpone the problem and cause it to fester like a wound

until the body begins to rot. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, example

gratia, dedicates one sentence to the whole problem of the Old Testament:

"The Old Testament is divinely inspired ....

even though

it does contain some imperfect and time bound

things''.

What an understatement! Neither in my years of theological

studies at a Pontifical University in Rome nor in my reading afterward

have I ever came across any catholic theological investigation into the

moral problems of the Old Testament and the repulsive portrayal of God

and His chosen people in some of its books. Why can questions not be asked

and things not be discussed? Is our faith so fragile and weakly founded?"

[A Catholic Priest, "B", (October 2005)]

I

think that the posting speaks for itself, without any need for comment

from me. Another correspondent replied:

I

think that the posting speaks for itself, without any need for comment

from me. Another correspondent replied:

"It seems to me that the principal issue

is how we are to define "inspiration."

As you and many others recognize, if we give God very great and direct

responsibility for all the words in the Hebrew Scriptures, and for the

expressions of His will that led to frightful acts of bloodshed, then we

end up with a highly unsatisfactory theology.

Was it God's will that the first-born

of Egypt be slain on a single night, or that the entire Egyptian army

and their horses be drowned in

the Red Sea, or that the aboriginal peoples of Palestine be exterminated?

No; but God allowed those stories to be written and preserved, because

they somehow reflect the truth of God's love for

Israel, and the importance of the covenant relationship.

Horrible stories such as the one about

Jephthah's daughter [Judges 11],

and, a favourite of mine, the one about the holy man of Judah [1

Kings 13], illustrate the awesome all-powerful

holiness

of God, and the reverence that human beings must feel for it; but they

should not be interpreted as saying positively that God desired and commanded

these things to be done.

Unfortunately, throughout history we have tended

to remain on the surface, and our wrong understanding of what the will

of God is has led to all sorts of terrible consequences. The Catholic Church

in its wisdom is selective in what passages from the Hebrew Scriptures

to include in its liturgy; so for the most part, in the Mass and the Office,

we do not stumble on very many corpses. For the most part; we do not suppress

Exodus, for example.

I am sorry that you are struggling with problems

of canonicity. By all means appeal to those who believe that Councils of

bishops have set all this straight, if it helps you; but I recommend a

more historical approach, which rejoices in all the rich literature that

is available to us, and which mourns the suppression or loss of so

much that we cannot see. I remind you of the practice of the authors of

the New Testament: when they wanted to quote from the Old Testament, they

most certainly did not restrict themselves to the Septuagint. They used

whatever Greek version they found convenient to their purpose, including

perhaps versions of their own out of Aramaic."

[A Catholic layman, "MS", (October 2005)]

Some incorrect or inadequate

solutions

The gravity of the dilemma expressed here has led various people to espouse

extreme solutions. I shall next review and criticize the main ones with

which I am familiar.

Gnosticism

There was a strand of Gnosticism which held that the creator god of the

Hebrew Scriptures was not at all the same as the Father of Our Lord Jesus

Christ. The latter is the true supreme God; the former is an incompetent

underling (the demiurge), who messed things up by creating matter. In this

tradition, the serpent of Genesis, is a hero who wishes to save humanity

from the mess that the demiurge created. On this basis, the whole of the

Old Testament; as received from the Jews is suspect and at best can only

be interpreted on the basis of a secret (arcane) and hidden (apocryphal)

knowledge (gnosis) that is not at all apparent either from the text or

the living tradition (of the Hebrew people) that gave rise to it.

The basic problem with this doctrine is that it makes out that all creation

is at root a mistake, that matter (and hence the body and sex is intrinsically

evil) and that (wo)man is pretty much irredeemable.

The creed of Toledo [Dz 28] anathematizes

those who say there is one god of the Old Testament and another of the

New.

This doctrine is also intentionally excluded by the Nicene

Creed:

"We believe in One God, maker

of Heaven and Earth; of all that is, visible and invisible."

In 1053 pope St Leo IX required Peter of Antioch to profess the same faith

in one divine author of Old and New Testaments [Dz

348]. Moreover, pope Clement VI makes it clear in his letter

to the Catholicos of Armenia that the books themselves and not merely the

dispensations are at issue:

"We ask if you believed and now believe

that the New Testament and Old Testament in all the books which the authority

of the Roman Church has handed down to us contain unquestionable truth

throughout". [Dz 570r]

The Oecumenical Councils of Florence [Dz 706],

Trent [Dz 783] and the Vatican all strongly

affirm the idea that there is one God jointly of both the Old and New Testament.

Marcionism

This was a more overtly Christian version of the same viewpoint. Marcion,

in the mid second Century, proposed that

Christians should accept as scripture only Paul's letters, and his

own de-Judaized form of the Gospel according to

Luke.

"Marcion went much further in his criticism

of the Old Testament than I would dream of going. He scrapped it completely,

even the 'good parts'. Even the fear of being considered a marcionite does

not dampen the voice within me that is asking the questions. Personally

- if this were merely a matter of taste annd choice - I too would scrap

the whole Old Testament; if that were the only way to get rid of the most

offensive parts of it. The Church's teaching that the whole Old Testament

(Septuagint version) is (in some sense) divinely inspired, forces us to

look for a less simple answer.

Unlike Marcion, I - and most Christians, I suspect

- have no big problems with the New Testamment. The Gospels - including

the infancy narratives - are for me historically and spiritually true (the

four Gospels are per se the life story of Our Lord in the flesh, and are

therefore historical, but more than historical, as they give us a history

that transcends facts and ordinary human conditions. The few factual discrepancies

between the Four Gospels reinforce the historical value, I find, rather

than detract. The supernatural details are no mere embellishments, but

belong to the essence of the narrative of Our

Lord's life, teaching, wonders, works, self-sacrifice and rising from the

dead. Religion without the supernatural is pointless.) But that is my view

- I do not know what the Church demands off us to confess as regards the

historicity of the Gospels."

[My original Priestly Correspondent, "B", (October

2005)]

Marcionism is open to more or less the same criticism and condemnation

as Gnosticism.

Dehebraicism

This is, perhaps, the conventional Catholic view. Basically, it is the

idea that Christianity and Judaism are more or less totally different religions.

The role of Judaism being only to prepare the way for Christianity, the

advent of which discontinuously replaced a "shadow belief" with "the true

substance of The Faith". On this view, the Jewish Scriptures exist only

to foreshadow the New Testament, and the Old Testament should always and

only be interpreted in the light of the New. Many great theologians, including

my hero Origen, held to this position.

It is well expressed in subsequent postings from "B", "MS" and "AC":

"It seems to me that the Old Testament

is the whole literary production of the early Hebrew people; which their

priests, being the natural keepers of the memory of the people, wished

to preserve for posterity. That collection of writings, both sacred and

profane, eventually acquired an aura of holiness, simply because it had

become so old and so familiar.

The Christian Church inherited the Old Testament

in toto in its Greek version, and considered the whole collection indiscriminately

to be sacred, because it had been used, venerated and quoted by Our Lord

and His Apostles. Thus we got stuck with both the good and the less good,

the useful and the less useful, the inspiring and the repulsive aspects

of the Old Testament. Those christians who actually read the Old Testament,

have been looking for an explanation ever since.

Historicity is the least of the problems regarding

the Old Testament. Its moral dilemmas are far more serious to me, and to

sincere seekers of the Truth, such as Simone Weil in the book 'Letter to

a religious', in which this young jewish philosopher expresses her

desire to be baptized a Catholic, but cannot bring herself to accept the

Old Testament!

I first read a copy of the Bible in the monastery,

when I was about sixteen or seventeen. Until then, I had only seen passages

of the Holy Scriptures in prayer books and in the Missal. I was shocked

to read in Leviticus that a man who sleeps

with another man should be outcast from society. Since I read the Bible

from the beginning, I quickly came across even worse sounding words in

my reading. This left a lasting impression upon me and put me off biblical

studies more or less up till now. I have always leaned towards Dogmatics

and Liturgy and Church History, and shunned biblical studies. I am now

rereading the Old Testament, to try to see it in another light.

However, I must confess, that the conversations

between Moses and God in Exodus sound frighteningly like the words of a

child who is trying to calm his somewhat confused, capricious, easily offended,

unpredictable, and potentially dangerous

alcoholic parent. This rereading of the Old Testament is not shedding

any positive light upon my questions.

For me the New Testament is the Holy Book of Christians

per se, whilst the Old Testament is more or less the background information

which we can consult in order to put the prophesied Coming of Our Lord,

His life and cultural/religious reference in its proper context and understand

it more fully. For ours is an incarnated God, and an incarnated religion.

The proper use of the Scriptures, as I see it, is to reverentially listen

to the relevant bits of it that are read or sung during the celebration

of the Liturgy of the Mass and the Divine Office.

My

faith as a Catholic does not depend directly upon the scriptures at all,

let alone the Old Testament. My belief in God depends upon the natural

revelation in nature and in my conscience. The further supernatural truths

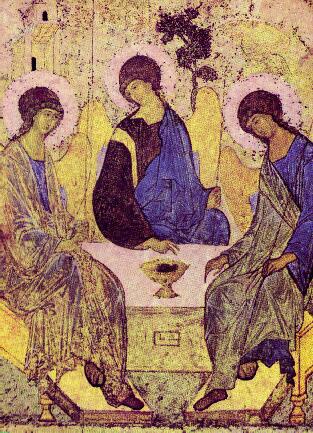

which God has wished to reveal about Himself: the

Trinity; the Incarnation; the Resurrection;

His

Virgin Mother; His Church; the

Eucharistic Sacrifice and Presence, these depend upon the Divine Revelation

as contained in the Living Holy Tradition,

of which the Liturgy is the privileged

place of expression, and the Holy Scriptures acquire their value and meaning

within the context of the Liturgy and the Tradition which it celebrates.

My

faith as a Catholic does not depend directly upon the scriptures at all,

let alone the Old Testament. My belief in God depends upon the natural

revelation in nature and in my conscience. The further supernatural truths

which God has wished to reveal about Himself: the

Trinity; the Incarnation; the Resurrection;

His

Virgin Mother; His Church; the

Eucharistic Sacrifice and Presence, these depend upon the Divine Revelation

as contained in the Living Holy Tradition,

of which the Liturgy is the privileged

place of expression, and the Holy Scriptures acquire their value and meaning

within the context of the Liturgy and the Tradition which it celebrates.

This is how see it, and this is why I write that

my faith does not depend directly and solely upon Scripture and the problems

which we are now discussing. Which means answers of any kind, or a lack

of answers, regarding the Old Testament, would not at all negatively affect

my Catholic faith, but honest and sincere answers could well have a positive

effect." ["B" (October 2005)]

"It is worth noting that we Christians have traditionally,

treated the Old Testament always as ancillary to the Christian revelation.

The first reading in today's Novus Ordo Lectionary is an excellent example.

Exodus 22:20-26 is from the long and complex legal code that give the Torah

its name. To Jews, this is the most important part of the Hebrew Scriptures,

the part that they spend the most time reading and discussing. To us, it

is mostly irrelevant, not to say boring, and we rarely look at it, privileging

much more the narrative portions of Torah, and the Prophets (including

the historical books and the writing prophets) and the Writings (especially

Psalms and the Wisdom literature). As is regularly the case, this passage

from Exodus has apparently been chosen to give something of an Old Testament

background to the Gospel lesson.

On the other hand, I think we never hear at Mass

Exodus 22:17-19, which is about three classes of people who must be put

to death (witches, people who have sex with animals, and people who offer

sacrifices to other gods); or Exodus 22:27-29, which is about offering

the first-born children to God, and the first-born of one's cows and sheep."

["MS"

(October 2005)]

"We have not to forget that the veil of the Temple

was torn apart at the moment of Christ's death. The Old Testament was

no more and the People of God are the baptised of the Church. The old

laws no longer have any validity. We Christians eat pork and seafood -

all the things that were purified by God (cf. St. Peter's vision of the

sheet containing "impure" animals for eating and the Angel's command to

kill and eat). Likewise, the old laws of the Torah are abrogated.

I

see the Old Testament is its allegorical and symbolic meaning - a preparation

for the Incarnation of Christ and the Redemption. The Holy Trinity is a

God

of love and the fulness of Revelation, for which the people of the

Old Testament were only prepared progressively. I have read the Bible entirely

cover-to-cover just once - I found much of the Pentateuch (apart from Genesis

and Exodus - with the Paschal theme) incredibly boring. What is

I

see the Old Testament is its allegorical and symbolic meaning - a preparation

for the Incarnation of Christ and the Redemption. The Holy Trinity is a

God

of love and the fulness of Revelation, for which the people of the

Old Testament were only prepared progressively. I have read the Bible entirely

cover-to-cover just once - I found much of the Pentateuch (apart from Genesis

and Exodus - with the Paschal theme) incredibly boring. What is

genuinely spiritual are the Prophets, the Wisdom

Books and the Psalms - that is something else, which have been sanctified

by Christ as were the old pagan mystery religions. I love the beautifully

erotic Song of Solomon.

For me, the beauty of Christianity is that it

is not merely a "Jewish heresy", but a recapitulation of the whole of human

experience, progress and aspiration, expressed in Paganism

and Judaism alike. The dogma of the Trinity "moderates" the stark monotheism

of Judaism and Islam, and gives us entirely different archetypes. Christianity

admits eroticism in the spiritual life, but Islam and Judaism

expect you to love (or rather serve

or submit to) God for absolutely nothing in return, as do many deformed

versions of Christianity."

[A second Clerical Correspondant "AC" (October

2005)]

As

I have made clear elsewhere, I largely repudiate

this position. While I accept that "MS" and "AC" are largely correct

in implying that for Catholics, the detailed regulations of the Mosaic

Law are almost entirely defunct; I must admit to finding the overall effect

and impact of the Liturgical Rubrics of Leviticus inspiring. Moreover it

must not be forgotten that neither the Ten Commandments nor the foundational

laws to "Love the Lord your God" and "Love

your neighbour" have been "abrogated"!

While not denying that "B" is right to raise the problem that he does,

neither claiming that it is at all easy to answer; nevertheless, for me:

As

I have made clear elsewhere, I largely repudiate

this position. While I accept that "MS" and "AC" are largely correct

in implying that for Catholics, the detailed regulations of the Mosaic

Law are almost entirely defunct; I must admit to finding the overall effect

and impact of the Liturgical Rubrics of Leviticus inspiring. Moreover it

must not be forgotten that neither the Ten Commandments nor the foundational

laws to "Love the Lord your God" and "Love

your neighbour" have been "abrogated"!

While not denying that "B" is right to raise the problem that he does,

neither claiming that it is at all easy to answer; nevertheless, for me:

The Catholic Religion is a developmental

continuation of the Judaic Tradition, not a replacement for it.

The New Testament should be read in the light of the Old Testament just

as much - if not more than - the Old should be read in the light of the

New.

Most "New Testament ideas" are in fact "Old Testament ideas" repackaged,

for example "Love your neighbour as yourself" [Lev

19:18,33].

Our Blessed Lord based his preaching on Old Testament themes and images.

For example:

".... while Jesus was standing there,

he cried out,

'Let anyone who is thirsty come to me, and let the one

who believes in me drink. As the scripture has said, "Out of the believer's

heart shall flow rivers of living water"'." [Jn

7:37-38] compare:

"Ho, everyone who thirsts, come to the waters;

and you that have no money, come, buy and eat! Come, buy wine and milk

without money and without price." [Is 55:1]

and also:

"A garden locked is my sister, my bride, a garden

locked, a fountain sealed. Your channel is an orchard of pomegranates

with all choicest fruits, henna with nard, nard and saffron, calamus and

cinnamon, with all trees of frankincense, myrrh and aloes, with all chief

spices a garden fountain, a well of living water, and flowing streams

from Lebanon." [Song 4:12-15]

"Come to me all who labour and are heavy laden,

and I will give you rest. Take my yolk upon you, and learn from me;

for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your

souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light".

[Mat 11:28-30] compare :

"Come close to me, you uninstructed .... I have

opened my mouth, and spoken: 'Buy her without money, put your necks

under her yolk, and let your souls receive instruction; she is not

far to seek.' See for yourselves, how slight my efforts have been to

win so much peace."

[Sir 51:23-30 NB this passage is not present

in all manuscripts of Sirach!]

Much of the Church's liturgical practice and ethical teaching originates

in the Old Testament.

Leviticus is the best justification for the elaboration of Catholic Ritual.

The psalms and Old Testament canticles are central to the Church's worship,

both in the Office and the Mass.

Some of the most profound insights of Scripture are to be found in the

Torah, see below.

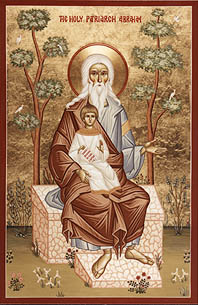

Many hugely inspiring examples of holiness and faithfulness are to be found

in the Old Testament: Abraham, Moses, Elijah, and Jeremiah to mention just

a few personal heroes.

"Let's not forget that the New Testament

is the maturity of the Old Testament. Just as little as we are going

to disregard the child in us now that we are mature, we equally can't disregard

the child of the Old Testament, now that we have the adult of the New.

The New Testament does not abrogate the Old Testament cultic code, but

gives it its fullest possible meaning. It's all about book (the Tanach)

versus person (Jesus Christ). Different paradigms, but the same phenomenon:

God's self-revelation to humans."

[A third Clerical Correspondent: "H" (October

2005)]

Spiritualization

The former position can give rise to the idea that the Old Testament has

to be "sanitized" in some manner; the "nasty bits" being radically re-interpreted,

almost as if they never meant what they manifestly did mean to their writers

and first readers. The great theologian Origen was especially keen to ignore

the plain meaning of Old Testament texts and to concoct mystical significances

for them, whether or not the literal meaning was problematic or not. For

Origen, God's inspiration of the text was only operative when it was read

within the Church by those with spiritual maturity and insight. The Word

of God was only present in the text for those able to rightly discern it.

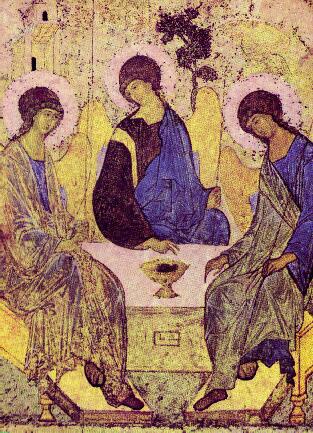

I believe that passages from either Testament can have secondary and

sometimes spiritual/mystical meanings which

may not have been either intended or apparent to their human authors, though

intended by God. For example, the deepest significance of the visit of

the three Angels to Abraham and of the encounter of Moses with God in the

Burning Bush was - I am sure - not realized by the author-editor(s) of

Genesis and Exodus. Nevertheless, I think that it is wrong simply to discount

the plain meaning of any Scriptural text. It seems to me that to do so

is to do violence to The Word of God - the core document of Sacred Apostolic

Tradition.

My Priestly Correspondent later enquired:

"Is the above supposed to connect to

the the immediately preceding long citation from me? I hope not, because

the whole point of my question is that the obvious, literal and primary

meaning of many Old Testament passages are offensive and need to be

taken seriously, not sterilized, spiritualized away, or analogized away

alla Origen. I do, of course, admit to several co-existing meanings, but

not in order to pretend that the originally meant meaning be conveniently

discounted." ["B" (October 2005)]

To which I respond that no such thought occurred to me! I said "can give

rise" not "will give rise". Of course, "B" has already said that he would

willingly excise those offensive passages (or even the Old Testament entire!),

if this was an option open to him.

Fundamentalism

This is easy to understand and express. It is the idea that whatever the

Bible says should always be taken literally, at face value. Hence, as the

Bible says that God on occasion commanded the Israelites to kill innocent

non-combatants, then one must accept that He did so and one must further

believe that this was a just and good thing to do; simply because God commanded

it. The basic problem with this "solution" is manifest: it makes God out

to be an arbitrary tyrant.

The following is a conflation of responses to our question from three

Fundamentalist-Evangellical web sites. I think that the text I present

is pretty representative of such thought.

Certain accounts within the Old Testament

depict God not as holy, kind, good, and merciful, but instead as unjust,

mean, vengeful and unforgiving.. It would seem, then, that the God of the

Old Testament is a God of wrath, and quite distinct from the God of the

New Testament.

The Extermination of the Canaanites

When the Israelites were commissioned to take the

land of Canaan, God instructed them to smite completely the native peoples,

and to show no mercy upon them. In fact, He is represented as having ordered

the destruction of entire cities, such as Jericho, just to allow the Jews

to have a homeland in the Middle East. How can this be reconciled with

the goodness of God?

Surely a loving God could not command

such a genocide.

Several things must be taken into consideration.

-

This argument is based on the unstated assumption

that the people whom God ordered destroyed were morally equivalent to the

Jews who replaced them. However, this is what the Bible says about the

people who were destroyed: "It is not for

your righteousness or for the uprightness of your heart that you are going

to possess their land, but it is because of the wickedness of these nations

that the Lord your God is driving them out before you, in order to confirm

the oath which the Lord swore to your fathers, to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob."

[Deut

9:5]

-

It must be noted that the Lord had been very patient

with these immoral pagan tribes for a long time. When Abraham first entered

Canaan, God promised that it would someday belong to his seed, but said

that it could not yet be theirs because "the

iniquity of the Amorite is not yet full" [Gen

15:16].

-

The Canaanite religion was a brutal system that may

have involved human sacrifice and even infanticide.

-

The destruction of these wicked people was for the

moral preservation of the nation of Israel.

-

God has the right to render judgement upon evil at

any time. No one has the right to criticize the moral activity of God unless

he can establish and defend some genuine moral standard apart from God:

and this no unbeliever can do!

The Biblical Imprecations

The "imprecatory" sections of the Scriptures are

those that contain prayers or songs for vengeance upon enemies, or which

end in triumphant praise at their destruction. How is it that such expressions

come to be part of divine revelation? These writings should not be viewed

as outbursts of vindictiveness characteristic of an inferior moral code.

It is wrong to take a low view of texts that were placed in the divine

record for a purpose. These prayers and songs express a zeal for God's

cause; a willingness to leave vengeance in His hands; and acknowledge that

punishment for sin is a part of the divine order.

-

The enemies of Israel were the enemies of Israel's

God.

-

Israel's defeat was a reproach to His Name.

-

The cause at stake was not merely the existence of

a nation, but the cause of divine truth and righteousness.

Unethical Actions by God

The Bible sometimes represents God as acting in ways

that seem to be unethical. For example:

-

concerning Pharaoh, God said: "I will harden his

heart" [Ex 4:21];

-

God says, apparently of the Mosaic Law: "I gave them

also statutes that were not good" [Ezk 20:25]!

-

and Jeremiah said: "Lord God, surely thou hast greatly

deceived this people" [Jer 4:10].

In order to correctly interpret such passages, one

must be aware of certain idiomatic traits of Biblical Hebrew. Active verbs

were used by the Hebrews to express, not just the doing of a thing, but

the granting of permission by an agent for a thing to be done; which the

agent is (mis)represented as doing. Hence, sometimes the Bible uses figurative

terminology, representing God as directly causing some action or effect,

when in reality He did not do so.

With reference to the examples cited above:

-

Pharaoh hardened his own heart, by yielding to the

enchantments of his magicians and refusing to listen to the testimony of

Moses.

-

When Ezekiel says that God gave statutes that were

not good, he means no more than that when stubborn people determined that

they did not want to abide by true justice, God permitted them to follow

the wicked statutes of the pagan nations around them.

-

When Jeremiah suggested that God deceived the people

of Israel, he meant only that the Lord allowed them to follow their own

paths of self deceit.

Those who respect the Bible as the Word of God must

realize that though certain passages of Scripture are difficult to understand,

there is always an explanation to be had. Many of the answers can be discovered

by means of patient and thorough research; and even where difficulties

remain, we must not charge God with error.

God in fact is not different from one Testament

to another. God's wrath and love are revealed equally in both Testaments.

Throughout the Old Testament we see God dealing with Israel in much the

same way as a loving father deals with an erring child. This is how we

later see God dealing with Christians "For

whom the Lord loves He chastens, and scourges every son whom He receives."

[Heb

12:6]. Throughout the Old Testament, we see

God's judgement and wrath poured out on unrepentant sinners. Likewise in

the New Testament we see that the wrath of God is still “revealed

from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men who suppress

the truth in unrighteousness” [Rom 1:18].

Even a quick reading of the New Testament makes it evident that Jesus

talks more about Hell than He does Heaven. Throughout the Bible we

see God lovingly and merciful calling people into a special relationship

with Himself, not because they deserve it but because He is a gracious

and merciful God, slow to anger and abundant in loving-kindness and truth;

yet we also see a holy and righteous God Who is the judge of all those

who disobey His word and refuse to worship Him.

While I think that there is some truth in the above, it is mixed in with

a lot of error!

Some first attempts at

an answer

My

third clerical correspondent wrote, addressing "B":

My

third clerical correspondent wrote, addressing "B":

"I battle, like you, to understand this.

I belong to a Calvinist-Reformed discussion group, and the moderator and

I have had a few interesting discussions about hell and why I find it unpalatable

to my sense of grace and mercy to believe in a "pizza

oven" where God fries little people like you and me for not wanting

to play with Him anymore.

This is a tough one, and I probably have more

questions than answers; but one thing I know is this: our human perception

of God taints and colours God. I think a whole lot of really 'primitive'

thinking by our Israelite ancestors in the faith is the source of these

odd descriptions of God. I simply cannot reconcile my understanding

and experience of God with a psychopathic tyrant who blows fire and smoke

from his nostrils.

What I think we need to learn from this

is that we need to allow God to reveal Himself to us as He is, and not

as We are. This is a fundamental perceptual principle:

We see as we are, and to change how

we see, we need to change who we are.

In Christ, we have been transformed into His likeness,

but the image is still lacking: good old Orthodox theology here! I think

we as fathers though we are evil (to use Jesus' words) know how to give

good gifts to our children because we empathize with them. Hence we should

not be surprised that God, too, knows this.

I so identify with what you are writing, you have

no idea, but let's not approach the problem with the idea of validating

or invalidating the Canon. This is not right. We have to engage with matters

such as these by keeping true to our Apostolic Faith. The Canon of the

Old Testament is inspired and is now part of our written Paradosis [=

Tradition - ed].

God speaks to us through it.

There must not be the slightest doubt

in our minds and hearts about this,

or else we loose connection with the Book

and its Tradition.

Our point of departure must be the perspective of

faith, or else we can just as well discuss the New York Times instead.

We see, in the pages of the Tanach [=

the Hebrew Bible - ed], many series of developments

and growth in understanding of the depositum fidei. Take for example

the almost 'primitive' use of the legendary and mysterious 'ephod' and

'urim and thummim' in the priestly office. By the end of the monarchy (certainly

by the end of the post-exilic period) the ephod (and probably also the

urim and thummim) were classified with the teraphim (household gods [e.g.

Gen 33:34]) and considered to be less than

acceptable for religious use. So, too, the early priestly function of providing

torah (oral instruction) to the people of God. Initially a priestly prerogative,

later disconnected from the Priesthood and administered by the Scribes

and Teachers of the Law, which also included lay people!

Things [seem to -ed] change

as our human capacity allows us to better understand.

No wonder Jesus pointed out to the Apostles that

even they could not bear to hear all there is to know, but that in the

age of the Paraclete, the revelation would become greater [John

16:12-15].

Although I honestly have few answers for you,

I have learned to marvel at how our own limitations are projected onto

God (the psychoanalyst in me, I confess!), and how easily we assume that

God is such and such because we are such and such. I think a society's

perception of God tells us who they were, and not who God is. God is, by

nature, unchangeable.

God needs no metamorphosis, we do.

I so love the words of Saint Paul in this regard:

"As

it is, to this day, whenever Moses is read, their hearts are covered with

a veil, and this veil will not be taken away till they turn to the Lord

.... and all of us, with our unveiled faces like mirrors reflecting the

glory of the Lord, are being transformed into the image that we reflect

in brighter and brighter glory" [2 Cor. 3:15-18].

It is in Jesus Christ alone that the transformation of the human soul takes

place and that a full and complete unveiling of the vagueness and uncertainties

of the past dispensations is experienced.

Our New Testament perspective of grace is the

point of departure we should use when reading the Old Testament, or else

we, like the Jews, read with our hearts "covered

with a veil".

["H" (October 2005)]

I am sure that a lot of what is going on in the Hebrew Bible's account

of God is in fact an account of (Wo)Man's developing

understanding of God. For this reason, it is important that we keep

tight hold of the whole account so that we remember how far we have come

and may get an impression thereby of how much further we may yet have to

go.

For example, I think it is unwise to remove all the sexist language

from the Bible. Not because I approve of the sexist attitudes of various

Biblical writers or because I think that they reflect the Mind of God:

no, but because this flawed language remains a

powerful witness to us that the whole of the language of Sacred Scripture

is human language - with all the glories and poetries

and inadequacies that this means. If St Paul could have culturally

(ill-)conditioned ideas about women, then he could have similarly inadequate

ideas about slaves or who knows what/who else.

And so could we!

Setting

the Context

Setting

the Context

It is vital to remind ourselves of the context of our question. Unlike

my correspondent "B", I find the Torah (otherwise known as the Pentateuch

or the Books of Moses) to be generally inspiring and profound documents.

I list below a few of the highlights:

-

God the Creator:

-

The Cosmos is created from nothing by an act of Divine Intellect [Gen

1],

-

by a separation of "positive from "negative" [Gen

1:4].

-

The Spirit of God is intimate with matter [Gen 1:2].

-

Hence, there is no "demiurge".

-

Hence also, matter is not intrinsically evil.

-

God is being-in-itself [Ex 3:13-15].

-

WoMankind is created in God's Image [Gen 1:26-27].

-

Gender and the Divine invitation to reproduce [Gen

1:27] pre-dates the fall.

-

Hence sex is intrinsically wholesome.

-

WoMen are not intended to be lonely [Gen 2:18-24],

but to have companions and live in community.

-

God the Redeemer, Friend and Lover of WoMankind:

-

God still cares intimately for WoMankind, even after they have sinned

[Gen

3:21].

-

God is willing to covenant and bind Himself to WoMankind [Gen

9:8-17; 15:17-20; 17:1-14 Ex 24].

-

God wants to dwell among the community of His people [Ex

29:38-46].

-

God is implacably opposed to human sacrifice [Gen

22:12 but cf Jdgs 11:29-40 Ezk

20:26 Ex 22:28-29].

-

God is a powerful deliverer and redeemer [Ex 12,

15:11-13, 18:10-12].

-

With God's help, it is entirely possible to defeat sin and to be a good

person

[Gen 4:6-7].

-

It is possible to become a friend of God [Gen 5:21-24,

Ex 33:11,18-34:9].

-

It is proper to argue [Gen 18:22-33] and fight

[Gen

32:24-32] with God.

-

God the Just Judge

-

The Ten Commandments [Ex 20:1-17].

-

Strangers and foreigners should be treated fairly and with consideration

[Ex

22:21-24].

-

Revenge is limited to like for like [Ex 21:24 Lev

24:20 Deut 19:16-21].

-

Love your neighbour as yourself, whether (s)he be Jew or Gentile [Lev

19:18,33].

Defining the Problem

Before

proceeding to attempt to formulate an answer to the problem at hand, it

is vital to clarify what exactly the problem is.

Before

proceeding to attempt to formulate an answer to the problem at hand, it

is vital to clarify what exactly the problem is.

-

God is sometimes represented as:

-

approving,

-

commanding, or

-

directly bringing about

-

actions that seem to be unjust, duplicitous or wicked.

-

Examples of God appearing (sometimes implicitly) to approve of wickedness

include:

-

God's acceptance of Jacob, after he had tricked his elder brother Esau

out of his birthright

[Gen 27-28].

-

The story of the young widow "Tamar" who disguised herself as a whore so

that she might have sex with her father in law, "Judah", who was refusing

to let her marry his youngest son, "Shelah", her brother-in-law who should

have been constrained to give her sons so that the name of her late husband,

"Er", would be preserved [Gen 38:6-26].

-

Moses' killing of the Egyptian overseer [Ex 2:1-5].

-

God's toleration of slavery and the abuse of slaves [Ex

21:20-21].

-

The duplicitous murder of Sisera, the general of a Canaanite army with

a tent peg [Jdgs 4,5] by Jael in the days

of Deborah the prophetess and ruling Judge of Israel.

-

The sacrifice of Jephthah's daughter [Jdgs 11:29-40].

-

Examples of the commanding of apparent wickedness include:

-

Abraham was ordered to cast out his concubine Hagar, and first born son

Ishmael, in favour of Sarah and Isaac [Gen 21].

-

Abraham was ordered to sacrifice his son Isaac [Gen

22].

-

God's injunction to execute all witches and mediums [Ex

22:18, Deut 13:1-5].

-

The Hebrews were ordered to wipe out the native peoples of Palestine, many

cities were to be put "under the ban" [Lev

26:7-8

Num 31:1-21 Deut 7:1-5; 20:10-18

Josh 7:16,18-21,25;8:1-2,7-8,19,22-29;10:28-43; 11:14-15].

-

The story of Israel's slaughtering all of the women and children of the

tribe of Benjamin in revenge for the murder of a Levite's concubine and

then Israel's kidnapping hebrew virgins from other tribes so that the few

Benjaminite men remaining might have wives and so continue their tribe

[Jdgs

19-21].

-

Examples of directly bringing about wickedness include:

-

The Flood [Gen 6-8]. However, this may have

been a natural disaster and only attributed to God's initiative: the punishment

of sinners.

-

The destruction of Sodom and Gomorra and the death of the wife of Lot

[Gen

19]. Once more, the destruction of the cities of the planes may

have been some kind of natural disaster, rather than an "Act of God" and

the story of the salinification of Lot's wife be nothing more than a fable.

-

God's abortive murder of Moses [Ex 4:24].

This is a very mysterious and garbled incident.

-

The plagues of Egypt, especially the Death of the Firstborn [Ex

6:28-12:32].

-

The drowning of Pharaoh's army [Ex 14:23-28].

It should be born in mind that this was a "them or us" situation.

-

God's commitment to wipe out the primitive populations of Palestine, including

the injunction to put many cities "under the ban" [Ex

23:23,27-30 Num 21:2-3,31-35 Deut 17-24;

11:23-25; 12:29; 20:1-4 Josh 10:10-11; 11:6-9,30].

-

God's anger towards the Hebrews after Aaron had set up the Golden Calf

for them to worship [Ex 32:1-14,35 Deut 9:13-14,19,25].

-

The death of two sons of Aaron [Lev 10:1-3].

-

The death of Korah and his men [Num 16].

-

The fiery serpents [Num 21:6-9].

-

Harsh threats to punish disobedience viciously [Deut

28:15-68; 31:16-21; 32:15-43].

-

The death of one prophet (who was killed by a lion) for having been deceived

another one [1 Kgs 13].

-

God gave the Hebrews "statutes

that were not good" [Ezk

20:25], commanding them to commit infanticide of their own firstborn

[Ezk 20:26, cf Ex 22:29, Lev 18:21].

The

following observations must be made immediately:

The

following observations must be made immediately:

-

Many of these incidents are reported in a partial and sometimes clearly

garbled manner.

-

The fact that the writer may seem to approve of something should not be

taken as meaning that God certainly does.

-

"God's approval" is sometimes only implicit or tacit; toleration might

be a better word to use than approval.

-

The fact that the text claims that something was explicitly commanded or

approved by God should not be taken as a definitive.

-

The distinction between "The priests or prophet commanded it in the name

of God" and "God commanded it to be done by the words of his priests or

prophet" was perhaps too subtle for the ancient Hebrews.

-

Sometimes events are ascribed to God in a quite arbitrary manner, see for

example [Num 11:1-2;33-34].

-

Given the rest of this chapter, it is pretty obvious that the phrase:

-

"the anger of the Lord was kindled, and the Lord

smote the people"

-

is a figure of speech meaning:

-

"something very unpleasant happened to the people".

-

I say this because

-

no pretext whatsoever is given to explain "God's anger" on the second occasion

-

and between the two incidents of "God's anger" there is a clear example

of God's gracious kindness, when He is presented as responding superabundantly

to complaints and moans from the Hebrews that they were fed-up of eating

manna and wanted fruit and meat and green vegetables instead [Num

11:4-6;10-11;18-20;31-32]!

Nevertheless, a number of serious issues remain to be dealt with. Later

on in this paper, I will attempt to do so, but first it is appropriate

to discuss how the canon of Scripture was established, and what is meant

by Scriptural Inspiration and Inerrancy.

How was the

canon of Scripture established?

The

following is a debate reported [October (2005)]

between my corespondent "H" and a Calvinist antagonist "C".

The

following is a debate reported [October (2005)]

between my corespondent "H" and a Calvinist antagonist "C".

[C] "What I am saying is that the canon

existed as an objective entity given by God from the moment each canonical

document was penned. The Spirit working in each canonical author imbued

the text with the necessary authority, and that same Spirit worked through

the text to impress that authority on any reader of the text: for one reading

in faith, this results in acceptance of its authority, and for one reading

in disbelief, a condemnation from on high. In either case, the authority

of the text is affirmed and confirmed by the Spirit speaking through the

text. This means that the locus of authority in determining or defining

the canon is not the church, but the Spirit."

[H] "You isolate the Spirit as if He were apart

from the Church, and as if the Church were merely accidental or even irrelevant

and unimportant to the work of the Spirit in defining the Canon. This is

not the Biblical teaching. Jesus promised to send to the Church “another

Paraclete” (advocate, intercessor, counsellor, support), 'the

Spirit of truth' [Jn

14:16] who will be 'with'

the Church, 'in'

the Church [Jn 14:17],

and 'on' the

Church [Acts 1:8].

In fact, the Spirit will also flow 'from'

the Church [Jn 7:38-39].

The Spirit is in the Church, and guides her into all truth [Jn

16:12-15].

It is in and with and through the Church

that the Spirit speaks.

To illustrate: the Canon of Scripture, Old

and New Testament, was finally settled by Athanasius in the East in 367

AD, and at the Council of Rome in 382 AD, under the authority of Pope Damasus

I. It was soon reaffirmed on numerous occasions. The same Canon was affirmed

at the Council of Hippo in 393 AD and at the Council of Carthage in 397

AD. In 405 AD Pope Innocent I reaffirmed the Canon in a letter to Bishop

Exuperius of Toulouse. Another council at Carthage, this one in the year

419 AD, reaffirmed the Canon of its predecessors and asked Pope Boniface

to 'confirm this Canon, for these are the

things which we have received from our fathers to be read in church.'

All of these Canons were identical to the modern Catholic-Orthodox Bible,

and all of them included the deuterocanonicals. This, surely, is a demonstration

of the Church's understanding of herself as vessel of the Spirit, and the

channel through which the Spirit speaks, and not as an obstacle or obsolete,

accidental bystander. The Canon was recognized under the guidance of the

same Spirit who inspired the Canonical writings."

[C] "In a way parallel to the private recognition

of the believer that the Gospel is true, so the church came to recognize,

through the working of the Spirit through the word, which documents were

canonical and which were not."

[H] "There was no canon of Sacred Scripture

in the early Church. There was no Bible apart from the Septuagint

Old Testament text. Of all the 'versions' of the Old Testament, this certainly

takes first place; since it is based on a pre-Masoretic Hebrew text. When

the Christians started citing not only Greek Epistles from her Apostles,

but also the Greek Old Testament, many Jews abandoned that text in favour

of the Hebrew version then current.

The Bible is the Book of the Church; She is not

the Church of the Book. Thus the Church has a Book and a Teacher: the Spirit

in the Church. It was the Church, guided by the authority of the Spirit

of Truth, which discerned which books were inspired by God. The Church

did not decide what the canon was going to be; she proclaimed what the

canon already objectively was. We agree on this.

Interesting discussion can be had over the 'protocanonicals'

and the 'deutoerocanonicals' of the New Testament, and how the Church's

Sacred Magisterium operated in this regard. What I don't understand is

what you mean by "the working of the Spirit

through the word". Shouldn't it be: "the working

of the Spirit through the Church"? Where does "The

Word" declare the canon of "The

Word"?

[C] "I believe that the great Oecumenical councils

can only claim the revelation of the Spirit derivatively through the word

of God, but that nonetheless their conclusions were thoroughly in accord

with the witness of the Scriptures."

[H] "Where do the Scriptures, then, define the

canon? If Councils only function 'in

accord with the witness of Scriptures'", then

where do the Scriptures witness to the content of canon? You are ignoring

how the Councils saw themselves. They clearly understood the Church to

be 'in the Spirit' when 'in Council'.

How can you accept as binding the Council's definition

of the New Testament Canon, and yet dismiss its definition of the Old Testament

Canon? Why, for the latter, do you prefer to accept the decision of a Synod

of Rabbinical Jews as authoritative?

We both know how complex a discussion of Canonics

can get, but a simple progression from primitive oral Paradosis is probably

as follows:

-

a pattern of teaching [Rom.

6:17],

-

traditions [2

Thes. 2:15],

-

a pattern of sound teaching [2

Tim. 1:13],

-

a deposit [2 Tim. 1:12],

-

a recognized canon.

Why do you assume that once the oral Paradosis or

Tradition gets to the "canonical stage", that the process

of Paradosis itself ceases? The Fathers know nothing of this!

St Francis de Sales wrote an article:

'The Protestant violation of Holy Scripture', [Burns and Oats: London,

(1886 AD)]. As an introduction paragraph he wrote: 'I

well know, thank God, that Tradition was before all Scripture, since a

good part of Scripture itself is only Tradition reduced to writing, with

an infallible assistance of the Holy Spirit. But, since the authority of

Scripture is more easily received by the reformers than that of Tradition,

I begin with the former in order to get a better entrance for my argument.'"

[C] "The word of God needs no external authority

to confirm its truth, only the Spirit speaking through the word."

[H] "You are not reflecting the Tradition of the

Fathers in your thinking. Whose Tradition are you reflecting, then?

The Spirit also speaks through His Church. It is from Holy Spirit and from

the teaching of the Holy Apostles, and their successors that we too come

to 'the knowledge of the truth'

and to 'true religion' [Tit.

1:1]. This is why the decisions that are made

when the Apostles (or Bishops) gather in Council are endorsed by the Holy

Spirit [Acts 15:28],

because it is in this manner that the Church exercises her witness, with

the Holy Spirit [Acts 5:32],

of the truth that is in Jesus Christ. Jesus promised to send the Church

'another paraclete, the Spirit of truth' [Jn

14:16].

Any

Bishop will tell you that individual opinions are relative in the absence

of Magisterial precedent. We are all free to think as we please, as part

of the vox populi in the Church, but when we put it all on the table and

the Church makes a definitive Magisterial statement, then individual opinions

are only indicative. Even if all the Fathers agreed in their writings on

some subject, these would be indicative only of their own private views

if the Church's Magisterium declared the opposite!

Any

Bishop will tell you that individual opinions are relative in the absence

of Magisterial precedent. We are all free to think as we please, as part

of the vox populi in the Church, but when we put it all on the table and

the Church makes a definitive Magisterial statement, then individual opinions

are only indicative. Even if all the Fathers agreed in their writings on

some subject, these would be indicative only of their own private views

if the Church's Magisterium declared the opposite!

Each protestant group has its own Paradosis that

directs its interpretation of Scripture and its practice, and it is this

unacknowledged 'tradition' that distinguishes each group from all others.

It is true that Jerome, and a few other isolated

writers, did not accept most of the deuterocanonicals as Scripture. However,

Jerome was persuaded, against his original inclination, to include the

deuterocanon in his Vulgate edition of the Scriptures. This is testimony

to the fact that the books were commonly accepted and were expected to

be included in any edition of the scriptures. Furthermore, in his later

years Jerome accepted certain deuterocanonical parts of the Bible. In his

reply to Rufinus, he arduously defended the deuterocanonical portions of

Daniel even though the Jews of his day did not. He wrote:

'What sin

have I committed if I followed the judgement of the Churches? But he who

brings charges against me for relating the objections that the Hebrews

are wont to raise against the story of Susanna, the Son of the Three Children,

and the story of Bel and the Dragon, which are not found in the Hebrew

volume, proves that he is just a foolish sycophant. For I was not relating

my own personal views, but rather the remarks that they [the Jews] are

wont to make against us'

[Against Rufinus 11:33].

Thus Jerome acknowledged the principle by which the

canon was settled: the judgement of the Churches. Other Fathers

that Protestants cite as objecting to the deuterocanon, such as Athanasius

and Origen, also accepted some or all of them as canonical. Athanasius,

accepted the book of Baruch as part of his Old Testament [Festal

Letter 39], and Origen accepted all of

the deuterocanonicals, he simply recommended not using them in disputations

with Jews!"

A Summary [much edited]

Apostolic authorship is the most obvious

and fundamental criterion for inclusion in the New Testament canon. But,

if you only use this criterion, you're in trouble: Paul's Epistle to the

Laodiceans was not included in the New Testament canon! One exception

to this rule is sufficient to sink it. The Apostle Paul is, in any

case, a real thorn in the flesh for anyone trying to maintain this as the

sole criterion for New Testament canonicity. Paul was not one of the

Twelve. The Twelve exercised their Apostolic Magisterium and judged

that Paul's teaching was of the Spirit [Gal.

2:2].

Apostolic approval, either explicit or tacit,

is another criterion for canonicity, but here again you are in trouble.

Anyone using this argument without reference to the Church's Magisterium,

perhaps to justify the inclusion of the Gospels in the canon, must also

include the writings of Clement, Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp of Smyrna

and possibly also Papias. These (excellent, wholesome and edifying) writings

were excluded on no other grounds than the judgement of the Spirit-inspired

Magisterium of the Bishops-in-Succession.

The idea that inspired texts make themselves apparent

to the reader is partly valid. In terms of the oral Paradosis: often the

'common sense of the faithful' is sufficient criterion for canonicity:

especially if that 'sense' is well informed by Paradosis. This best accounts

for the inclusion of the Gospels in the canon, for example. On this basis

alone, one cannot exclude the possibility of future addition to the canon,

if suitable documents were to be found. With all the textual finds of the

last few years, don't be surprised if '1 and 3' Corinthians appear from

somewhere to take their place next to our current '2 and 4' Corinthians!

Of course, the way in which the Old Testament

canon was quite different, and not all the writings of the Old Testament

are from prophetic sources either! Here, the only criterion was the Church's

discernment of what was true, under the guidance of Holy Spirit.

It is Holy Spirit in the Church, who

speaks to the Church, through the Church.

How is Sacred Scripture

inspired?

The following is heavily indebted to the article by J.H. Chrehan S.J. to

be found in "A Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture"

(Nelson, Edinburgh 1953), especially for the quotations, references

and outline argument. The original article is well intentioned and very

informative but, it seems to me rather complacent. In particular it glosses

over the teaching of pope Benedict XV ["Spiritus

Paraclitus"], which is generally incompatible with the thesis that

he wishes to propose and that I have taken further forward. As is now typical

of neo-conservative Catholics, Chrehan relies too much on - what was for

him - the latest teaching document to emerge from the Vatican, namely the

encyclical "Divino Afflante".

Jewish

understanding of inspiration

Jewish

understanding of inspiration

The Torah or Pentateuch was commonly held by the Jews to have come from

God entire, in much the way that Muslims believe that the Koran was given

to Mohammed. Even the final verses of Deuteronomy were sometimes thought

to have been dictated by Moses before his death, though generally it was

held that Joshua appended them. The prophets were thought to have been

less completely controlled by God than Moses in their utterance; while

the historians were accounted to have been merely assisted by God. The

foundation for the Jewish theory of degrees of inspiration is "If

there be among you a prophet of the Lord, I will appear to him in a vision,

or I will speak to him in a dream. But it is not so with my servant Moses

.... for I speak to him mouth to mouth and plainly: and not by riddles

and figures. He hath seen the Lord" [Num 12:6].

For the Jews, inspiration and inerrancy were tied up with the idea that

what

had been foretold by God's prophet would certainly happen: even though

sometimes

at least it did not! They regarded most of the books in their canon

as being prophetical: for Moses was the greatest prophet, the psalmist

was the royal prophet and even the Books of Kings were called prophetical.

Moses is presented as writing his canticle at God's dictation, [Deut

31:19]. Moreover,

"Baruch wrote from the mouth

of Jeremiah all the words of the Lord which he spoke to him, upon the roll

of a book",

[Jer 36:4].

Philo considered Scripture to have been written

by men in ecstasy.

[It was] "a god-indwelt possession and

madness." [The prophet] "uttereth nothing

of his own, but entirely what belongs to another who prompts him the while

.... The wise man is a resonant instrument, struck and beaten by

the unseen hand of God".

This inspiration was extended by him to the translators of the Septuagint,

in the well known story of its origin which he recounts. The Targum, too,

had its share of inspiration, for Jonathan ben Uzziel was said to have

composed the Targum of the prophets with aid from Haggai, Zechariah, and

Daniel! When it was finished, a voice from heaven asked: "Who

has revealed my secrets?"

The

Witness of the New Testament

The

Witness of the New Testament

The Apostles reaffirm the idea that the Scriptures are inspired. St Paul

famously says: "All Scripture, inspired of God, is

profitable to teach, to reprove, to correct, to instruct in justice"

[2 Tim 3:16]. St Peter, agrees : "Prophecy

came not by the will of man at any time: but men spoke on the part of

God; inspired by the Holy Ghost" [2 Pet

1:21]. This is an echo of an earlier impromptu sermon:

"God

hath spoken by the mouth of his holy prophets from the beginning of

the world" [Acts 3:21]. Of all the

New Testament writings, only the Apocalypse makes any claim to be inspired

[Apoc 1:19,22:6], but St Peter expresses some kind of belief in the inspiration

of "the epistles of our dearest brother Paul",

when he says: "The unlearned and unstable wrest these

epistles, as they do also the other Scriptures, to their own destruction".

The Witness of The Fathers

Pope St Clement I indicates that

he regard Paul's letters to Corinth as inspired:

"In truth it was by the Spirit that he

sent you a letter about himself Kephas and Apollos." [1

Clem 47:3]

The old man to whom St Justin ascribes

his conversion says:

"There were long ago men more ancient

than any of the philosophers now in repute, men who were happy, upright,

and beloved of God, who spoke by the divine Spirit and gave oracles

of the future which are now coming to pass. These men are called prophets.

They alone saw the truth and proclaimed it to men, not practising any restriction,

not made shamefaced nor swayed by boastfulness, but proclaiming that

and that alone which they heard and saw, being filled with Holy Spirit.

Their writings are still extant." [Dial. Tryph

3-7]

This shows that Christians of that time accepted the Old Testament as inspired.

In a passage dealing with parables St

Irenaeus says:

"If we cannot find explanations of all

things which require investigation in the Scriptures, let us not seek for

a second god beyond The One Who Is, for that would be the height of impiety.

We ought to leave such things to God who is after all our maker, and most

justly to bear in mind that

the Scriptures are perfect, being spoken by

the Word of God and by his Spirit,

while we, as lesser beings, and indeed as the

least of all, in comparison with the Word of God and with his Spirit, in

that proportion fall short of the understanding of God's mysteries."

[Adv. Haer. 2:4]

Athenagoras adopts the comparison of the

player and the musical instrument which occurs in Philo:

"The words of the prophets guarantee

our reasoning .... for they, while

the reasoning power within them was at

a stand,

under the motion of the divine Spirit, spoke forth

what was being wrought in them, the Spirit working with them, as it were

a piper who breathed into his pipe" [Legat.

9]

Theophilus of Antioch, writes:

"The men of God were spirit borne and

became prophets; being breathed upon by God himself and made wise, they

were taught of God, holy and just. Thus they were deemed fit to receive

the name of the instruments of God, and were enabled to hold the wisdom

of God by means of which they spoke about the creation of the world

and all else .... and there were not one or two of them but many, and all

spoke in harmony and accord with each other of those things which happened

before their time, or during their time, and also of what is now coming

to pass in our days ..... These statements of the prophets about justice

and

those of the gospels are found to be in harmony because their authors

were all spirit borne and spoke by the Spirit of God".

[Patrologia Greca, ed Migne: 6 1064,1137]

The Scholastics and Protestants

In general the Middle Ages took the question of how Scripture was inspired

for granted. However, Richard Fitzralph (Archbishop of Armagh c 1356),

did advance the discussion when he asserted in his dialogue with John the

Armenian, that Holy Spirit is the primary author of Scripture,

while the human writer is the immediate author.

The Catholic theologian Lessius rejected that understanding of verbal

inspiration which amounts to "divine ventriloquism" and Cardinal Bellarmine

supported him in this. In contrast to this sensible view, the Anglican

heretic Cartwright, held to a strict (almost Koranic) verbal inspiration

even to the exclusion of all textual corruption:

"Seeing the Scripture wholly both for

matter and words is inspired of God, it must follow that the same words

wherein the Old Testament and New Testament were written and indited by

the hand of God do remaine".

The Swiss "formula consensus" (1675 AD) has

it that all vowel points and accents were due to inspiration and that no

barbarisms of language could occur in biblical Greek or Hebrew! However,

it was not just heretics that held such views. The Catholic theologian

Banez did too! The Oecumenical Vatican Council, refrained from pronouncing

on the dispute between him and Lessius.

Modern

re-evaluation of the concept of inspiration

The Oecumenical Vatican Council explicitly rejected the idea that the Church

not only guarded the canon of Scripture but actually gave the books their

inspired character, adding that it was because they had God for their (principal)

author and as such were given to the Church that the books of the Bible

were to be regarded as inspired [Dz 1787].

Pope Leo XIII taught in "Providentissimus Deus" (1893) that inspiration

included both:

-

the arousing of the human author to write by the action of Holy Spirit;

-

and the assistance given by the Spirit in the work of composition,

so that those things only and wholly which He wished should be written

down [Dz 1952].

The Thomists developed an instrumental theory of Inspiration. As an

instrument is said to have no action at all except as moved or applied

by some higher agent, so the biblical authors are envisaged to be set in

motion by God to produce even such effects as might be within their natural

powers. In this view, inspiration is a divine action upon the intellect

under whose impetus it clearly perceives exactly what God wishes to be

written, and then sets about writing it. This replaces a word-for-word

Divine Dictation by a "total" Inspiration. On this theory, God is the total

author (and not merely principal) of the text while the human writer was

to be regarded as the total author, in his degree.

The Divine Condescension

Now, whereas the idea of instrumental cause surely applies to Inspiration,

it would seem that a mere instrument would be unintelligent and passive

in the hands of God. On the contrary, in the co-authorship of the Scriptures

God acts in and through the human author, as an author, and

not merely through him as an unskilled tool. We have already read that

the human authors themselves:

-

"spoke on the part of God"

-

"spoke by the divine Spirit and gave oracles of the

future"

-

"saw the truth and proclaimed it to men"

-

"proclaiming that and that alone which they heard

and saw"

-

"being breathed upon by God himself and made wise,

they were taught of God, holy and just."

-

"were enabled to hold the wisdom of God by means

of which they spoke"

-

"were all spirit borne and spoke by the Spirit of

God"

Hence the Thomist theory is inadequate. While God did work through

human writers to produce the Scriptures as through instruments (just as

John Damascene speaks of the Sacred Humanity of Christ being the instrument

of His Divinity); because the instruments were human God worked

in

them too; the human writers making full use of their intellect and will

as they co-operated with God's grace. Of course, the testimony

of Athenagoras is somewhat contrary to this.

This is well demonstrated by the language of the Second Book of Maccabees,

where the human author reflects on his labours of composition; their difficulty,

purpose, and method. While God often gave the prophets their theme by direct

revelation, so that they were well aware that they dealt with God, this

was not always so. God worked with different individuals for different

ends in different ways. He could just as well motivate a man to write a

summary of Jason's histories of Judas Maccabeus' revolt against Macedonian

rule, protect him from making any substantive error, and by condescension

allow him to give vent to his weariness; the compiler being entirely

unaware that he walked with God. Clearly the subjective experience of the

writer of the Apocalypse, who was acutely conscious of the fact that he

was being inspired will have been entirely different that of the writer

of the Second Book of Maccabees, who - pretty clearly - was not!

The collaboration of God and the human writers was by no means hypostatic!

In each case, there was a distinct and beloved human

person and identity involved in the work, alongside (but under the

direction of) Holy Spirit! God entirely respected the autonomy of the human

authors, allowing them to exercise their own skills, express their own

thoughts and manifest their own personalities as they wrote under His influence.

Divine condescension is so gracious in supporting the human author's autonomy

that it must be supposed that its only limit is set by the need that the

final outcome of the process be entirely fit for God's purpose. As Pope

Pius XII put it:

"Catholic theologians, following the

teaching of the holy fathers and especially of the Angelic and Common Doctor

have investigated and explained the nature and effects of divine inspiration

better and more fully than was the custom in past centuries. Starting from

the principle that the sacred writer is the organon, or instrument, of

the Holy Spirit, and

a living and rational instrument,

they rightly observe that under the influence

of the divine motion

he uses his own faculties and powers

in such a way that from the book which is the

fruit of his labour all may easily learn the distinctive genius and individual