Why

Eternal Punishment?

Why

Eternal Punishment?Return to Theological Thoughts.

At the one extreme, the Gnostics taught that Man doesn't need God in order to be good. Either (wo)men are all basically good or can easily gain an adequate idea (knowledge or gnosis) of what it is to be good and can then become so with some effort. Such a belief is liable to be linked with the "universalist" view: that whether or not damnation is possible in principle, in fact no-one is ever damned.

At the other extreme, Luther taught that Man is utterly wicked and remains so even with God's help. Such a belief is liable to be linked with Calvinist doctrine: that few people escape damnation, and that those who do escape do so by the arbitrary whim of God.

Although original sin - the degree of separation from God that all humans experience from the start of their lives in this world - does not involve any radical depravation of human nature, it denies (wo)men the only context and environment in which they can prosper and attain their true potential. Rapidly, concupiscence sets in as the conscience becomes malformed by habituated mistaken judgements that are the inevitable consequence of ignorance and short-sightedness.

Nevertheless, even without specific Divine help, (wo)men are capable of objectively just acts. The conscience is not absolutely vitiated by concupiscence. Very often, very many people, have a very good idea of what is kind and loving and just. Very often they have the complete competence to act on this perception. Very often nothing stands in the way of their accomplishing the good deed that would naturally follow from such a perception.

It

seems to me that Hell (or "the

destructions", in Jesus' words) exists simply and only because it

is an option chosen by some sinners. Rather than to repent (change

their life style and philosophy, not just regret and so apologize for past

actions) and endure the stressful reformation of his will: the hard-hearted

offender against justice prefers to live eternally by his own subjective,

mistaken and false values and to refuse to adopt objective, true and so

wholesome values. In the last analysis, the only sin that matters is conceit.

This

is "the sin against Holy Spirit that cannot be forgiven", because it

asks for no forgiveness. It is self-satisfied with its poor lot. It

prefers its own poverty to the abounding riches of God, for it will not

admit that it is mistaken in its judgement.

It

seems to me that Hell (or "the

destructions", in Jesus' words) exists simply and only because it

is an option chosen by some sinners. Rather than to repent (change

their life style and philosophy, not just regret and so apologize for past

actions) and endure the stressful reformation of his will: the hard-hearted

offender against justice prefers to live eternally by his own subjective,

mistaken and false values and to refuse to adopt objective, true and so

wholesome values. In the last analysis, the only sin that matters is conceit.

This

is "the sin against Holy Spirit that cannot be forgiven", because it

asks for no forgiveness. It is self-satisfied with its poor lot. It

prefers its own poverty to the abounding riches of God, for it will not

admit that it is mistaken in its judgement.

It is uncongenial to modern minds to conceive of Hell as a place or at least condition of unending (but not necessarily thereby infinite or unlimited) suffering. However, this is the overwhelming testimony of, Scripture, Tradition and the Magisterium. I take this to be so manifest that I shall not bother to quote any authorities. However, I think the case is not as clear cut and quite so "horrid" as many pre 1960's Catholic propagandists or preachers might have had one believe.

Why

Eternal Punishment?

Why

Eternal Punishment?"Abraham believed God, and it was reckoned to him as righteousness" [Rom 4:3].So this system, arrangement or economy was just as operative both before and under the Mosaic dispensation as under the New Covenant. In the book of Wisdom we find it written:

"....thou art merciful to all .... and thou doest overlook men's sins, that they might repent. For thou hast loathing for nothing that thou hast made, for thou wouldst not have made it if thou hadst hated it. How would anything have endured if thou hadst not willed it? Thou sparest all things, for they are thine, O Lord who lovest the living"There is no notion here that a single sin necessitates Divine vengeance, but rather that God "bends over backwards" to excuse and forgive: because He loves all that He has made and wants sinners to repent.[Wis 11:23,24,26] .

The notion of "Justification by Faith through Charity" is not specific to the Gospel, but is part of the general dispensation available to all men of good-will [II Tim 2:4]. God's grace can work within the heart of any sinner, given an attitude of faith, to effect the necessary reformation by nurturing the additional "Theological Virtues" of Hope and, pre-eminently, Charity. Still, a degree of Faith, Hope and Charity are necessary preconditions for anyone to be a "friend of God". If they are lacking, Purgatory is no option, and Hell is the only prospect facing the recalcitrant sinner.

As

I've already mentioned, there is a paradox here. God, who is all-powerful

and all-loving, desires everyone to be saved. To this end, God gives all

(wo)men "sufficient grace" to be saved. Yet not all are saved. Why? As

I understand it, there are three generic answers to this problem. The

controversy generated has generally been heated and given rise to extreme

degrees of ill will: simply because the issues involved are very delicate.

For myself, I well recall being sent into a serious three day depression

by a Priest of Opus Dei, who insensitively and almost gleefully argued

(as best I recall) that those who have not had the Gospel preached to them

explicitly have no chance of being saved!

As

I've already mentioned, there is a paradox here. God, who is all-powerful

and all-loving, desires everyone to be saved. To this end, God gives all

(wo)men "sufficient grace" to be saved. Yet not all are saved. Why? As

I understand it, there are three generic answers to this problem. The

controversy generated has generally been heated and given rise to extreme

degrees of ill will: simply because the issues involved are very delicate.

For myself, I well recall being sent into a serious three day depression

by a Priest of Opus Dei, who insensitively and almost gleefully argued

(as best I recall) that those who have not had the Gospel preached to them

explicitly have no chance of being saved!

Grace is not an Aristotelian substance. It is a process; an engagement; an encounter with God. It is the helping hands offered by parents to their child who is learning to walk. It is the roar of approval from the crowd of supporters at the sports stadium or fans at the rock concert. It is the compassionate caress or smile of encouragement offered to the person who is suffering. It is the conversation of sharing between friends. It is the embrace of lovers.

Many graces given by God do not result in the entire effect toward which they are directed, while other graces do elicit the effect that was envisaged. Graces of the first kind are calledsufficient graces. They give the potential to do good, without necessarily bringing the good act itself to pass, since the recipient could and did in fact resist them. Graces of the second kind are calledefficacious. They not only give us the potential to do some good, but in fact enable us to actually accomplish it.

"If any one saith, that all works done before Justification, in whatsoever way they be done, are truly sins, or merit the hatred of God; or that the more earnestly one strives to dispose himself for grace, the more grievously he sins: let him be anathema." [Oecumenical Synod of Trent: session VI: canon 7]According to Pelagius' mortal enemy St. Augustine of Hippo, the Englishman believed that (wo)men were naturally capable of pleasing God and so earning His approval. Hence, Pelagius (I think rightly) believed that it was possible for those who have never heard the Gospel to be saved:

“.... the human race .... if it is self-sufficient for fulfilling the law and for perfecting righteousness [as the Pelagians falsely contend], ought to be sure .... of everlasting life, even if in any nation or at any former time faith in the blood of Christ was unknown to it .... Before, however .... the actual preaching of the Gospel reaches the ends of all the earth .... what must human nature do .... but believe in God who made heaven and earth, by whom also it perceived by nature that it had been created, and lead a right life, and thus accomplish His will, uninstructed with any faith in the death and resurrection of Christ [the Pelagians say]?The (I think correct) belief of the early Church that (wo)men can do no salvific good work without grace was so firm that Pelagius found it necessary to argue that the natural gift of human free will itself, or the recollection of the forgiveness of sins, or of the good example of Christ is the grace without which we can do no good.[St Augustine of Hippo: "On Nature and Grace"]

“Pelagius’ book contains and asserts this view .... where he says that he ought not to be reputed as defending free will as unhelped by the grace of God, since he says that the ability 'to will and to do' .... any good has been implanted by our Creator in our human nature, and that manifestly this was the grace of God, as understood by the doctor of grace himself, which is common to pagans and Christians, wicked and good, unbelievers and believers.” [St AugustineThe local Council of Carthage, held in 418 AD in the presence of St. Augustine and later confirmed by Pope St. Zosimus, non-infallibly (but I think correctly) condemned the proposition (attributed to Pelagius) that: wo(men) can with difficulty "do good, in a way that fulfils the purpose of the Law and produces the fruit of salvation" without any grace:of Hippo: letter 186]

“Also it has pleased, that if anyone shall have said, that the grace of justification is given to us so that we may be able to fulfil easier through grace what we are commanded to do through free choice, as if, were grace not given, even without it we would be able to fulfil the divine commandments, although not indeed easily, let him be anathema. For the Lord spoke of the fruit of the commandments, where He did not say, without Me ye are able to do with a greater difficulty, but he said: ‘without Me ye can do nothing’.”[Council of Carthage: AD 418, Canon 5]

Well, if this could have been done, or can still be done, then for my part I have to say what the apostle said in regard to the law: ‘then Christ died in vain’. For if he said this about the law, which only the nation of the Jews received, how much more justly may it be said of the law of nature, which the whole human race has received, If righteousness come by nature, ‘then Christ died in vain’.Taking St. Augustine literally, one would have to conclude that Enoch, Abraham, Moses, Elijah, and St John the Baptist, among many others, are all damned. Indeed if the phrase "and the sacrament of the blood" is insisted on, then even "the repentant thief" must now be in Hell: in direct contradiction with the explicit testimony of Our Blessed Lord! Any interpretation that is placed upon At Augustine's words which makes it possible to avoid this conclusion: and I am pretty sure that he would not have wanted his words to be understood in this way, will inevitably open up the possibility of other (wo)men of good being graciously redeemed on the basis of an implicit faith in Christ, and an implicit desire for Baptism and Holy Communion.

If, however, Christ did not die in vain, then human nature cannot by any means be justified and redeemed from God's most righteous wrath .... except by the faith and the sacrament of the blood of Christ.”[St Augustine of Hippo: "On Nature and Grace"]

Nevertheless, it is certainly true that some early theologians (I think very wrongly) explicitly rejected any such possibility:

"Grace is not properly esteemed by any one who supposes that it is given to all men, when not only does The Faith not pertain to all, but even at the present time some nations may yet be found to whom the preaching of The Faith has not yet come. But the Blessed Apostle says: ‘How then are they to call upon Him in whom they have not believed? or how shall they believe in Him whom they have not heard? but how are they to hear, without preaching?’ Grace, then, is not given to all; for certainly they cannot be participants in that grace, who are not believers; nor can they believe if it is found that the preaching of The Faith has never come to them at all."However, the teaching of even a good number of such authorities cannot be taken as determinative of Apostolic Tradition. This is mainly because it is clear in reading their works that they are not considering all the issues and possibilities, but simply giving a naive reaction to an inadequately posed question.[Synodal Epistle of St. Fulgentius and other African Bishops]

Often, the question is seen as one of justifying God's seemingly unreasonable and unkind actions in terms of a narrow legalism:

"[The Lord] says to Moses, 'I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.' So it depends not upon man's will or exertion, but upon God's mercy .... So then he has mercy upon whomever he wills, and he hardens the heart of whomever he wills."[The Apostle Paul: Rm. 9:15-18]

"Faith, then, as well in its beginning as in its completion, is God's gift; and let no one have any doubt whatever, unless he desires to resist the plainest sacred writings, that this gift is given to some, while to some it is not given. But why it is not given to all ought not to disturb the believer, who believes that from one all have gone into a condemnation, which undoubtedly is most righteous; so that even if none were delivered therefrom, there would be no just cause for finding fault with God."Such arguments are correct as far as they go, but entirely miss the point at issue![St Augustine of Hippo: "Predestination of the Saints" Ch 16] "God wills to manifest his goodness in men: in respect to those whom he predestines, by means of his mercy, in sparing them; and in respect of others, whom he reprobates, by means of his justice, in punishing them .... Yet why he chooses some for glory and reprobates others has no reason except the divine will. Hence Augustine says, 'Why he draws one, and another he draws not, seek not to judge, if thou dost not wish to err.'"

[St Thomas Aquinas: "Summa Theologica I:23:5" ,citing St Augustine: "Homilies on the Gospel of John 26:2"]

St. Augustine's book "On Grace and Free Will" is largely a exposition of his conviction that (wo)men can do no "good works", without grace:

“And therefore he makes strong the flesh of his arm who supposes that a power which is frail and weak (that is, human) is sufficient for him to perform good works, and therefore puts not his hope in God for help.....In all of the above, the saint fails to clarify whether the good acts that he is discussing are merely objectively just or also subjectively charitable: good works proper, and so meritorious. Moreover, the saint never deals with the issue as to whether sanctifying grace can exist apart from an explicit faith in Christ and explicit adherence to His Church.

So now let us see what are the divine testimonies concerning the grace of God, without which we are not able to do any good thing....

So that a man is assisted by grace, in order that his will may not be uselessly commanded....

Nevertheless, lest the will itself should be deemed capable of doing any good thing without the grace of God, after saying, ‘His grace within me was not in vain, but I have laboured more abundantly than they all’, St. Paul immediately added the qualifying clause, ‘Yet not I, but the grace of God which was with me’.....

Were grace only to withdraw itself, man falls, not raised up, but precipitated by free will. Wherefore no man ought, even when he begins to possess good merits, to attribute them to himself, but to God, who is thus addressed by the Psalmist: ‘Be Thou my helper, forsake me not’. By saying, ‘Forsake me not’, he shows that if he were to be forsaken, he is unable of himself to do any good thing.....

Here John the Baptist says of Christ: ‘Of His fulness have we all received, even grace for grace’. So that out of His fullness we have received, according to our humble measure, our particles of ability as it were for leading good lives.....

For when the command is given ‘to work’, their free will is addressed; and when it is added, ‘with fear and trembling’, they are warned against boasting of their good deeds as if they were their own, by attributing to themselves the performance of anything good.....

But when a man knows sin, and grace does not help him to avoid what he knows, undoubtedly the law works wrath. And this the apostle explicitly says in another passage. His words are: ‘The law worketh wrath’....

Not that the law is evil; but because they are under its power, whom it makes guilty by imposing commandments, not by aiding. It is by grace that any one is a doer of the law; and without this grace, he who is placed under the law will be only a hearer of the law.”[St Augustine of Hippo: "Grace and Free Will", Ch 6, 7, 9, 12, 13, 21, 22, 24]

It should already be apparent that I am no enthusiast for St. Augustine's doctrine of the relationship between grace and free-will. I believe that in his wholesome zeal to defend the Apostolic Tradition from the Pelagian error that (wo)men could earn or merit God's approval without God first deciding to reach out to them, he came at least close to the error that Origen warned against and which I will quote once more:

"This Epistle to the Romans is accounted more difficult to understand than the other Epistles of the Apostle Paul, this arises in my judgement from two reasons. One of these is the fact that he uses language which at times is involved and wanting in precision. The other is that in this Epistle he raises many problems, and especially those on which the heretics usually rely in their attempts to show that the reason of each of our actions must be assigned not to intention, but to some natural peculiarity. From a few texts in this Epistle they attempt to overthrow the meaning of the whole of Scripture, which teaches that freedom of will was bestowed upon man by God."[Origen: Preface to Romans, in "Selections from the Commentaries and Homilies of Origen", p 120-121 translator: R.B. Tollinton]

"as often as we do good God operates in us and with us, so that we may operate"and it never compromises the freedom to resist, as is taught infallibly by the Oecumenical Synod of Trent:

[Second Council of Orange, canon 9]

"If any one saith, that man's free will moved and excited by God, by assenting to God exciting and calling, nowise co-operates towards disposing and preparing itself for obtaining the grace of Justification; that it cannot refuse its consent, if it would, but that, as something inanimate, it does nothing whatever and is merely passive; let him be anathema."The Jesuit theologian Molina maintained that when grace is efficacious, it is so by virtue of human consent, foreseen by God. We shall shortly see that this theory is rejected by the Thomists, on the grounds that it implies a passivity in God relative to human Free Will.[Oecumenical Synod of Trent :Session VI ,canon 4]

"The idea that God does not allow anyone to perish for want of grace is crucial for a Molinist. The Jesuit theologian Pohle answers the question 'how God provides for the salvation of the heathen' in his book 'Grace Actual and Habitual' by first stating that whereas the Catechism says that six distinct revealed truths must be believed for salvation, it is not certain that anything other than a belief in God and that He is a rewarder of virtue is necessary for salvation. He then argues that even if the stricter view is true the six revealed truths need only be believed 'implicitly'.

The scholastics maintained that one must explicitly believe in the Trinity, Incarnation, Redemption and the Church in order to be saved, and that other doctrines need only be believed 'implicitly', in perhaps a general act of faith.

Molinists extend this principle and argue that in order to be saved, one need not explicitly believe anything identifiably Christian, but that it suffices to be a person of good will.

Pohle then discusses three commonly proposed hypotheses, as to how God might elicit explicit faith in a person of good will if, as the Thomists assert, this be required:Pohle assumes that many heathen will be saved, because (as has been for some time the common view of theologians) God grants to all (wo)men sufficient grace to be saved. Hence he rejects the three hypotheses as manifestly absurd because they are clearly not in fact “the ordinary means of conversion”.

- by directing a missionary to them,

- by sending an angel to them or

- by illuminating them internally.

[Closely based on a text by Thomas Sparks]

"The implicit faith theory is far more plausible, for it postulates no miracles, implicit faith being independent of the external preaching of the Gospel, just as the baptism of desire is independent of the use of water .… Some theologians hold that those to whom the Gospel has never been preached, may be saved by a quasi-faith based on purely natural motives.... For the rest, no one will presume to dictate to Almighty God how and by what means He shall communicate His grace to the heathen. It is enough, and very consoling, too, to know that all men receive sufficient grace to save their souls, and no one is eternally damned except through his own fault."On the one hand, this view neatly exonerates God from responsibility for damning anyone, and suggests that it is only wilful obduracy that prevents anyone obtaining Eternal Life. After all, Jesus taught that all it took to "enter the Kingdom" was to receive the Gospel "like a child" [Mk 10:15] and to keep the commandments [Mk 10:19]. He did not think this task impossible, at least not in whatever sense He meant it to be understood by the rich young man who asked him "what must I do to inherit eternal life?" We can see this in the fact that "Jesus looking upon him, loved him" [Mk 10:19-21], when he claimed "Teacher, all these I have observed from my youth." If the task was truly impossible, then the young man would have been either lying or mistaken, and in neither case would Jesus have failed to correct him.[Joseph Pohle SJ "Grace Actual andHabitual" 1914, p185-6]

On the other hand, it is difficult to see how God can be said to be Almighty, if his grace is so easily frustrated by human Free Will. Couldn't God astutely organize circumstances for each of his creatures so that their Free Will never came into conflict with His grace? In fact it seems that reality is far removed from such a cosy arrangement. While some people have quite easy lives, with few challenges to their faith; others have to contend with emotional, material and spiritual turmoil that tends directly to confound their faith and commitment to justice. Of course, it is not necessarily those who experience the easy option who are "faithful to the truth", and those who suffer many difficulties who fall by the wayside: a life of few challenges can result in complacency, a life full of disasters can result in someone clinging stubbornly to God, the only steadfast refuge in a volatile world.

"According to the catholic faith we also believe that after grace has been received through baptism, all baptised persons have the ability and responsibility, if they desire to labour faithfully, to perform with the aid and cooperation of Christ what is of essential importance in regard to the salvation of their soul. We not only do not believe that any are foreordained to evil by the power of God, but even state with utter abhorrence that if there are those who want to believe so evil a thing, they are anathema."Calvinists believe that when God gives a (wo)man the grace that enables him to come to salvation; they always respond, and never reject this grace. This is the doctrine of irresistible grace. It amounts to the idea that God forces people to come to him, against their will. This doctrine is contrary to Scripture, which gives clear indication that grace can be resisted. Stephen Protomartyr tells the Sanhedrin, "You always resist the Holy Spirit!" [Acts 7:51]. For this reason some Calvinists prefer the term "efficacious grace." According to Blaise Pascal, this idea: that God's enabling grace is intrinsically efficacious so that it always produces salvation is common territory with Jansenists (a form of Calvinism that grew up within the French Catholic Church) and Thomists.

[Second Council of Orange: Concluding Statement]

This is the principal issue between Thomists and Molinists. The former claim that enabling grace is efficacious by its very nature: because of the kind of grace it is, it always produces the effect of salvation. Molinists claim that enabling grace is only sufficient of itself: it is then made efficacious by man's free assent, co-operation and consent.

"If any one saith, that man's free will moved and excited by God, by assenting to God exciting and calling, nowise co-operates towards disposing and preparing itself for obtaining the grace of Justification; that it cannot refuse its consent, if it would, but that, as something inanimate, it does nothing whatever and is merely passive; let him be anathema."[Oecumenical Synod of Trent :Session VI ,canon 4]

This is, it seems to me, an attempt to "both have one's cake and eat it". If God does not want anyone to be damned, why doesn't God give everyone "efficient" grace? Is there some quota or limited supply of the stuff? Why doesn't God arrange circumstances in such a way in fact that all people are saved? If God can't do this, then it would seem that the Jesuit position is recovered. If God could do so but in fact chooses not to, the Calvinist position is recovered.

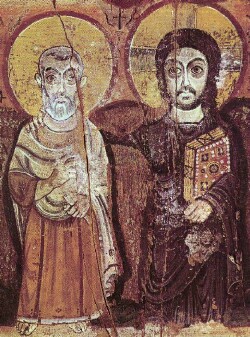

Byzantine

theology

Byzantine

theology"We believe the most good God to have from eternity predestinated unto glory those whom He hath chosen, and to have consigned unto condemnation those whom He hath rejected; but not so that He would justify the one, and consign and condemn the other without cause. For that were contrary to the nature of God, who is the common Father of all, and no respecter of persons, and 'would have all men to be saved, and to come to the knowledge of the truth'; [1 Timothy 2:4] but since He foreknew the one would make a right use of their free-will, and the other a wrong, He predestinated the one, or condemned the other.

And we understand the use of free-will thus:

The context of this document is important. A certain Cyril Lucar became the Patriarch of Constantinople in 1620 AD. Before this, he had studied for a while in western Europe. In 1629, a "Confession of Faith", written in Latin and ascribed to Cyril, was published in Geneva.that the Divine and illuminating grace,

But to say, as the most wicked [Calvinist] heretics do .... that God, in predestinating, or condemning, had in no wise regard to the works of those predestinated, or condemned, we know to be profane and impious. For thus Scripture would be opposed to itself, since it promiseth the believer salvation through works, yet supposeth God to be its sole author, by His sole illuminating grace, which He bestoweth without preceding works, to shew to man the truth of divine things, and to teach him how he may co-operate therewith, if he will, and do what is good and acceptable, and so obtain salvation. He taketh not away the power to will: to will to obey, or not obey him.(which we call preventing grace) being as a light to those in darkness,

to those that are willing to obey this

by the Divine goodness imparted to all;(for it is of use only to the willing, not to the unwilling)

there is consequently granted particular grace;

and co-operate with it, in what it requireth as necessary to salvation,which, co-operating with us,

But those who will not obey, and co-operate with grace;

and enabling us,

and making us perseverant in the love of God,

that is to say, in performing those good things that God would have us to do,

and which His preventing grace admonisheth us that we should do,

justifieth us, and maketh us predestinated.and, therefore, will not observe those things that God would have us perform,

and that abuse in the service of Satan the free-will, which they have received of God to perform voluntarily what is good,

are consigned to eternal condemnation.But than to affirm that the Divine Will is thus solely and without cause the author of their condemnation, what greater calumny can be fixed upon God? and what greater injury and blasphemy can be offered to the Most High? For that the Deity is not tempted with evils, [cf. James 1:13] and that He equally willeth the salvation of all, since there is no respect of persons with Him, we do know; and that for those who through their own wicked choice, and their impenitent heart, have become vessels of dishonour, there is, as is just, decreed condemnation, we do confess.

But of eternal punishment, of cruelty, of pitilessness, and of inhumanity, we never, never say God is the author, who telleth us that 'there is joy in heaven over one sinner that repenteth' [Luke 15:7]. Far be it from us, while we have our senses, thus to believe, or to think; and we do subject to an eternal anathema those who say and think such things, and esteem them to be worse than any infidels.

["Decree III of The Confession of Dositheos, Patriarch of Jerusalem",

being Chapter VI of the Acts and Decrees of the Synod of Jerusalem (A.D. 1672)]"We believe man in falling by the original transgression to have become comparable and like unto the beasts, that is, to have been utterly undone, and to have fallen from his perfection and impassability, yet not to have lost the nature and power which he had received from the supremely good God. For otherwise he would not be rational, and consequently not man; but to have the same nature, in which he was created, and the same power of his nature, that is free-will, living and operating. So as to be by nature able to choose and do what is good, and to avoid and hate what is evil.

For it is absurd to say that the nature which was created good by Him who is supremely good lacketh the power of doing good. For this would be to make that nature evil: than which what could be more impious? For the power of working dependeth upon nature, and nature upon its author, although in a different manner. And that a man is able by nature to do what is good, even our Lord Himself intimateth, saying, even the Gentiles love those that love them. [Matthew 5:46; Luke 6:32]

But this is taught most plainly by Paul also, [Romans 2:14] and elsewhere expressly, saying in so many words, 'The Gentiles which have no law do by nature the things of the law.' From which it is also manifest that the good which a man may do cannot forsooth be sin.

For it is impossible that what is good can be evil. Albeit, being done by nature only, and tending to form the natural character of the doer, but not the spiritual, it contributeth not unto salvation thus alone without faith, nor yet indeed unto condemnation, for it is not possible that good, as such, can be the cause of evil. But in the regenerated, what is wrought by grace, and with grace, maketh the doer perfect, and rendereth him worthy of salvation.A man, therefore, before he is regenerated, is able by nature to incline to what is good, and to choose and work moral good. But for the regenerated to do spiritual good - for the works of the believer being contributory to salvation and wrought by supernatural grace are properly called spiritual - it is necessary that he be guided and preevented by grace, as hath been said in treating of predestination; so that he is not able of himself to do any work worthy of a Christian life, although he hath it in his own power to will, or not to will, to co-operate with grace."

["Decree XIV of The Confession of Dositheos, Patriarch of Jerusalem",

being Chapter VI of the Acts and Decrees of the Synod of Jerusalem (A.D. 1672)]

"In its eighteen articles [it] professed virtually all the major doctrines of Calvinism; predestination, justification by faith alone, acceptance of only two sacraments (instead of seven, as taught by the Eastern Orthodox Church), rejection of icons, rejection of the infallibility of the church, and so on. In the Orthodox church the Confession started a controversy that culminated in 1672 AD in a convocation by Dositheos, patriarch of Jerusalem, of a church council that repudiated all Calvinist doctrines and reformulated Orthodox teachings in a manner intended to distinguish them from both Protestantism and Roman Catholicism." [The Encyclopaedia Britannica]

Why then did God create Lucifer? Once He did, why did He put Lucifer in such a position that he "failed the test": why, for that matter, was there any need to risk corrupting his initial good will?

The only answer that can possibly be made to these questions is "because of Love", but this is itself problematic. While it is loving "to create", and loving "to give freedom to", and even loving "to allow to fail" (in order to allow the one who fails to learn from their failure) it doesn't seem loving "to allow to fail absolutely" (and so for no purpose).

The

other side of the question is, of course, just as problematic: "Given his

position and access to God; why did Lucifer sin?" One presumes that

in order to constitute the Angels as His Friends, God had to give them

(as all sentient beings) the chance to choose for or against him of their

own Free Will. This amounts to deciding in a state of partial ignorance

and so on the basis of doxa: faith; rather than on the basis of episteme:

full and clear knowledge. Given such a real choice, it would seem inevitable

that some should take the wrong option. If none had turned away from God,

then it would seem that no real choice was available. Even the Incarnate

Word of God was subject to such an option. Though it was impossible

that the Son should rebel against or be separated from the Father, nevertheless

in His sacred humanity Jesus experienced the ultimate doubt regarding God

and a total loss of whatever episteme he may have habitually enjoyed. Hence

He cried out in utter distress: "My God, My God,

why hast thou forsaken me?" Whereas the Christ passed this test

(as was inevitable, given his divinity) at the cost of ultimate anguish,

and so become the Head of Creation; the original "chief creature", Lucifer,

failed: even though the crisis that he had to endure was much less and

was well within his capabilities of winning through.

The

other side of the question is, of course, just as problematic: "Given his

position and access to God; why did Lucifer sin?" One presumes that

in order to constitute the Angels as His Friends, God had to give them

(as all sentient beings) the chance to choose for or against him of their

own Free Will. This amounts to deciding in a state of partial ignorance

and so on the basis of doxa: faith; rather than on the basis of episteme:

full and clear knowledge. Given such a real choice, it would seem inevitable

that some should take the wrong option. If none had turned away from God,

then it would seem that no real choice was available. Even the Incarnate

Word of God was subject to such an option. Though it was impossible

that the Son should rebel against or be separated from the Father, nevertheless

in His sacred humanity Jesus experienced the ultimate doubt regarding God

and a total loss of whatever episteme he may have habitually enjoyed. Hence

He cried out in utter distress: "My God, My God,

why hast thou forsaken me?" Whereas the Christ passed this test

(as was inevitable, given his divinity) at the cost of ultimate anguish,

and so become the Head of Creation; the original "chief creature", Lucifer,

failed: even though the crisis that he had to endure was much less and

was well within his capabilities of winning through.

If God hadn't made Lucifer, it would have been possible to accuse Him of a kind of cowardice or censorship or conceit. How could God "know" that such a glorious being would "go bad", unless He gave him a chance to prove himself? God should have given reality to he who was conceived in the Divine Mind, and let him answer for himself. Nothing else would be fair! For God to chose to deny being to a potential creature just because He "knew" that Lucifer would rebel, would have been conceited!

Moreover, it may be that there is no real difference between God conceiving of a possibility in the abstract and God making that possibility real. In which case the question "Why did you make this mess of a Cosmos?" makes a lot less sense, as it is totally unreasonable to blame an infinite and omniscient God for considering all self-consistent possibilities. What matters in justice is that, given the fact of our Cosmos, God has done everything possible to aid and help and save all those sentient creatures that it contains.

Perhaps our Cosmos is not all that God has made. Perhaps there are Worlds that God has made in which Lucifer did not fall. Perhaps we will never know this; perhaps it is not our business to know.

My

attempt at a solution.

My

attempt at a solution."The sin of the first man has so impaired and weakened free will that no one thereafter can either love God as he ought or believe in God or do good for God's sake, unless the grace of divine mercy has preceded him ...." [Second Council of Orange: Concluding statement]"For every salutary act internal supernatural grace of God (gratia elevans) is absolutely necessary"

[Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma: Dr Ludwig Ott IV.I.8]"as often as we do good God operates in us and with us, so that we may operate"

[Second Council of Orange, canon 9]"man does no good except that which God brings about"

[Second Council of Orange, canon 20]."Whoever says that without the predisposing inspiration of the Holy Ghost and without his help, man can believe, hope, love, or be repentant as he ought, so that the grace of justification my be bestowed upon him, let him be anathema" [Oecumenical Synod of Trent: session VI: canon 3]

"[The Lord] says to Moses, 'I will have mercy on whom I have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I have compassion.' So it depends not upon man's will or exertion, but upon God's mercy .... So then he has mercy upon whomever he wills, and he hardens the heart of whomever he wills." [Rm. 9:15-18]Moreover, the offer of friendship is always at God's initiative and on His terms. Fallen, finite and sinful (wo)man is in no position to make the first move!

"If any one saith, that all works done before Justification, in whatsoever way they be done, are truly sins, or merit the hatred of God; or that the more earnestly one strives to dispose himself for grace, the more grievously he sins: let him be anathema." [Session Six: Canon VII]in conformance with the wholesome doctrine of the Confession of Dositheos. Nevertheless, none of these are significant as far as the eternal destiny of that person is concerned: unless they are subjectively motivated by an (implicit) faith in and love of Justice Itself: God. In which case, their agent is already a friend of God, though without knowing it. This love of Justice is sanctifying grace, and being God itself is entirely from God HimSelves. It is certainly not merited by any human action, rather it is disclosed as being already present in someone's life, unmerited and unexpected."If any one saith, that the fear of hell (whereby, by grieving for our sins, we flee unto the mercy of God, or refrain from sinning) is a sin, or makes sinners worse; let him be anathema." [Session Six: Canon VIII]

"If any one saith, that by faith alone the impious is justified; in such wise as to mean, that nothing else is required to co-operate in order to the obtaining the grace of Justification, and that it is not in any way necessary, that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his own will; let him be anathema." [Session Six: Canon IX]

"The true light that enlightens every man was coming into the world."

[The Gospel of John: Chapter 1 verse 9]"The Kingdom of Heaven is like treasure hidden in a field,

which a man found and covered up;

when in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field."

[The Gospel of Matthew: Chapter 13: verse 44]"The Kingdom of Heaven is within you: and whosoever knoweth himself shall find it."

["New sayings of Jesus", discovered at Oxyrhynchus 1903,

trans. Greenfell & Hunt, pub 1904, OUP: for the Egypt Exploration Fund]

"Raise the stone and thou shalt find me. Cleave the wood and I am there."

["The Logia", discovered at Oxyrhynchus 1897,

trans. Greenfell & Hunt, pub 1904, OUP: for the Egypt Exploration Fund]"as often as we do good God operates in us and with us, so that we may operate"

[Second Council of Orange, canon 9]"We also believe and confess to our benefit that in every good work it is not we who take the initiative and are then assisted through the mercy of God, but God himself first inspires in us both faith in him and love for him without any previous good works of our own that deserve reward, so that we may both faithfully seek the sacrament of baptism, and after baptism be able by his help to do what is pleasing to him."

[The Second Council of Orange, Concluding Statement]

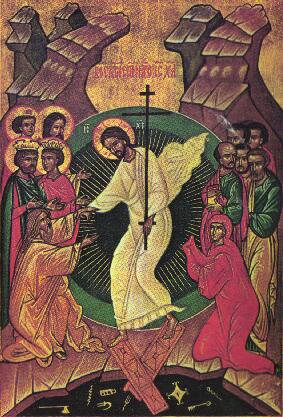

God

is the Great Seducer of Souls

God

is the Great Seducer of Souls"God wills to manifest his goodness in men: in respect to those whom he predestines, by means of his mercy, in sparing them; and in respect of others, whom he reprobates, by means of his justice, in punishing them .... Yet why he chooses some for glory and reprobates others has no reason except the divine will. Hence Augustine says, 'Why he draws one, and another he draws not, seek not to judge, if thou dost not wish to err.'"Taken literally, Thomas' teaching is simply true: except that the notion of "punishment" itself is complex and problematic. St Augustine is wise in warning against attempting to understand why God's invitation to some is effective and to others ineffective. We cannot possibly fathom what it might mean for One who is outside time to "choose" anything, still less to understand why He chose one option rather than another! Nevertheless, the uncritical use of the word choose is dangerous. It could be taken to mean that God chooses not to go the extra mile with some people: as if he decided beforehand that some were simply not worth bothering with.

[Summa Theologica I:23:5, citing Augustine, Homilies on the Gospel of John 26:2.]

An extreme version of this interpretation is "double predestination", a heretical doctrine constitutive of Calvinism. This claims that, in addition to positively electing some people to salvation (in consideration of their response to His sufficient prevenient grace); God also purposefully and deliberately causes others to be damned, (seemingly in order that Hell should be well stocked). A less extreme version is "passive reprobation": a doctrine characteristic of Thomism. This claims that while God positively predestines some people to salvation by lavishing on them infallibly self efficient grace, He simply passes over the remainder: granting them only "sufficient" grace that inevitably turns out to be ineffective. They do not come to God, but it is because of their sin, not because God positively damns them.

I find the Thomist stance distasteful in the extreme. I readily admit that trying to understand why God does and doesn't do things is a forlorn endeavour. We simply don't have the required extra temporal perspective: still less the wisdom to appreciate what we would learn if somehow we were to impossibly gain this viewpoint! Nevertheless, the impression that lingers in my heart after coming up against the idea of "passive reprobation" is of an arbitrary and capricious deity: rather than Substantial Love, who wills that all (wo)men be saved.

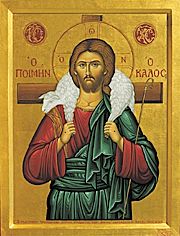

God

is indiscriminate

God

is indiscriminate"....thou art merciful to all .... and thou doest overlook men's sins, that they might repent. For thou hast loathing for nothing that thou hast made, for thou wouldst not have made it if thou hadst hated it. How would anything have endured if thou hadst not willed it? Thou sparest all things, for they are thine, O Lord who lovest the living"God's offer of friendship to a sinner is unmerited. It cannot be elicited. Hence, in some sense God could be choosy about who He invites to be His friends; though given that no-one deserves this grace, it is difficult to see how God could be choosy without being both irrational and unjust. In fact God is indiscriminate. Jesus socialized with the dregs of society: whores and fraudsters. It is fairly clear that the Tradition has it that God offers everyone His friendship, see Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma: Dr Ludwig Ott IV.I.11.2c. This is clearly the teaching of the Confession of Dositheos:[Wis 11:23,24,26] .

"the Divine and illuminating grace ..... by the Divine goodness imparted to all; to those that are willing to obey this ..... and co-operate with it, in what it requireth as necessary to salvation, there is consequently granted particular grace; which .... justifieth us, and maketh us predestinated."

"Then he said to his servants, 'The wedding is ready, but those invited were not worthy. Go therefore to the thoroughfares, and invite to the marriage feast as many as you find.' And those servants went out into the streets and gathered all whom they found, both bad and good; so the wedding hall was filled with guests.One should first note that party invitations were sent out indiscriminately, and then that the wedding hall is neither "Heaven" or "The Church Triumphant": it contains "both bad and good". The "man who had no wedding garment", for whatever reason, himself believed that he had no valid explanation for the fact. We are told that when challenged: "he was speechless". I have heard this explained by saying that wedding garments were provided by the host at the door, and to enter without donning one was an act of great discourtesy; but no matter!

But when the king came in to look at the guests, he saw there a man who had no wedding garment; and he said to him, 'Friend, how did you get in here without a wedding garment?' And he was speechless. Then the king said to the attendants, 'Bind him hand and foot, and cast him into the outer darkness; there men will weep and gnash their teeth.' For many are called, but few are chosen." [Mat 22:8-14]

Even though the unsuitably attired wedding guest is forcibly expelled from the marriage feast, the king addressed him as "friend". Moreover, our Lord does not say that the man is to remain in "the outer darkness" for ever, but only that: "there men will weep and gnash their teeth".

Our Lord seems to be saying that God invites (almost?) every (wo)man to be His friend; but that some (too many?) fail to respond in an appropriate way: by taking up the free offer of the wedding garment (God's gracious offer of forgiveness and transformation) and so exclude themselves from the Good Things that God has stored up for His Faithful.

The "called" are then those whom God wants to befriend. The "chosen" are those that select themselves, as in the story of Gideon's choice of shock troops:

"And the LORD said to Gideon, 'The people are still too many; take them down to the water and I will test them for you there; and he of whom I say to you, "This man shall go with you," shall go with you; and any of whom I say to you, "This man shall not go with you," shall not go.' So he brought the people down to the water; and the LORD said to Gideon, 'Every one that laps the water with his tongue, as a dog laps, you shall set by himself; likewise every one that kneels down to drink.'It may even be that the real choice is positive, for some specific purpose; rather than negative, as in damnation and a final rejection.

And the number of those that lapped, putting their hands to their mouths, was three hundred men; but all the rest of the people knelt down to drink water.

And the LORD said to Gideon, 'With the three hundred men that lapped I will deliver you, and give the Mid'ianites into your hand; and let all the others go every man to his home.'"

[Jdgs 7:4-7]