During the fourteenth century, it was not uncommon for nobles to go without shoes inside buildings or at “high society” events (reference Grandes Chroniques de France; folio 3v The crowning of Charles VI). Likewise, we may reference images such as /i>Le Songe du Verger; folio 1v The Churchman and the Knight Debate, to see that the knight and the “Churchman” are wearing only hose in an out of doors setting before a royal court. Albeit an illumination of a dream, the artist must have been familiar with such practices in his everyday life.

I have as not yet been able to discover a clear-cut practice as to which occasions called for shoes. My best speculation is quite a simple one; shoes were worn to protect hose from moist earth or perhaps to add a layer of insulation to the feet at colder times or terrain. I chose the term moist as it is very evident large numbers of the shoes illuminated from this period do not appear to be water resistant anywhere but their soles. Their low cut sides, perforated decorations, or the occasional fabric-top styles would do no more to keep out water then our similar motifs today.

A healthy number of shoes illuminated in manuscripts and other artwork of the 1300’s tended to be free of decoration and either dark brown or black in color. I have noticed a trend for illuminators to show decorated shoes on the feet of the central figures in their works. One may presume this refers to the fact that the higher ones social class the more decoration they were allowed to have or afford. Since we do know of sumptuary laws restricting the use of certain material and decoration in dress of this period, it is a logical theory.

The extended point of the toes on shoes (and patyns) were referred to as either Crackowes, after the city of Crakow (Poland), or poulaines derived from the word Poland. The latter of these two terms was most widely used in texts of the day. This new fashion trend is thought to have been introduced to Western Europe with the marriage of Richard II and Anne of Bohemia as Poland was, at that time, under Bohemian rule.

General Fabrication:

The turn-shoes before you are not based on any one pair found in history; instead they are a conglomerate based upon the information gathered in my research. I created the base design around the concept of water / mud resistant footwear. While the lower cut side (associated with the Latchet type or category) was a common shoe of the 14th-century, I chose a design drawn from manuscript Roy 14E, III. from the British Museum. The wearer is described as a traveler. The shaping of the shoe appears to be divided down the top arch of the foot. The vamp appears to remain solid on the instep and opens on the outside to be more reminiscent of the lower cut shoes described above. These shoes are not detailed with any decoration nor do they show a method of closure. Since there are no laces depicted in the illumination I referenced for the shoe design, I was left to presume either a button or buckle was used to keep the strapping tight over the foot. A button closure is illustrated with in the same manuscript on an apparent servant holding a decanter of sorts, but ultimately I was forced to choose the closure blindly. There does not appear to be enough finds as of 1988 in the excavations in London to merit a category for button closures in Shoes and Pattens, but I decided to use them for this entry anyway. Since the shoe itself is not a common design, I felt the use of a button closure as rare as it seems to be, would not be outside the realm of possibility on it. I will continue research towards find another example of their use for future reference. I was also fond of an embellishment shown on a scabbard from early-to-mid 14th-century and chose to use it to “cap” the vines decorating each shoe. I based my carvings very tightly on these images. The materials I used are as follows: 5-6 ounce bovine leather X-acto blade Glover’s needles A pin vice (to hold a glover’s needle and pierce holes prior to stitching) Linen Bee’s wax (for linen) 1/4" steel rod (for forcing the poulaine right-side out) A swivel knife Oil based dye Neat’s-foot oil As with most of my projects, there are several points of interest that I have discovered in this venture. Below are the most significant or helpful to first time shoemakers. Turning the poulaine right side out is very difficult. It will take a great deal of force and effort on even a shorter length such as mine. I have heard the argument that the longer shoes did not have their vamp and sole sewn together up the full length of the shoe. I do not personally agree with that for the reasons stated below the image, but I am by no means an expert on medieval shoes. If you note the area designated by the red arrow, you can see a distinct change in the visibility of the stitches holding the shoe together. This is one point those who believe the poulaine tip is finish stitched after turning. I have noted if you stretch the seam enough during the turning process or pack in too much stuffing trying to give the poulaine it’s shape, this effect can be duplicated. Additionally, at the tip of the poulaine you can see a conspicuous lack of stitches. During the turning of my shoe, I experienced a phase that duplicated this appearance just prior to the last bit of the vamp rolling over. In my experience, the pucker designated by the blue arrow was caused by an internal stitch (i.e. made prior to turning).

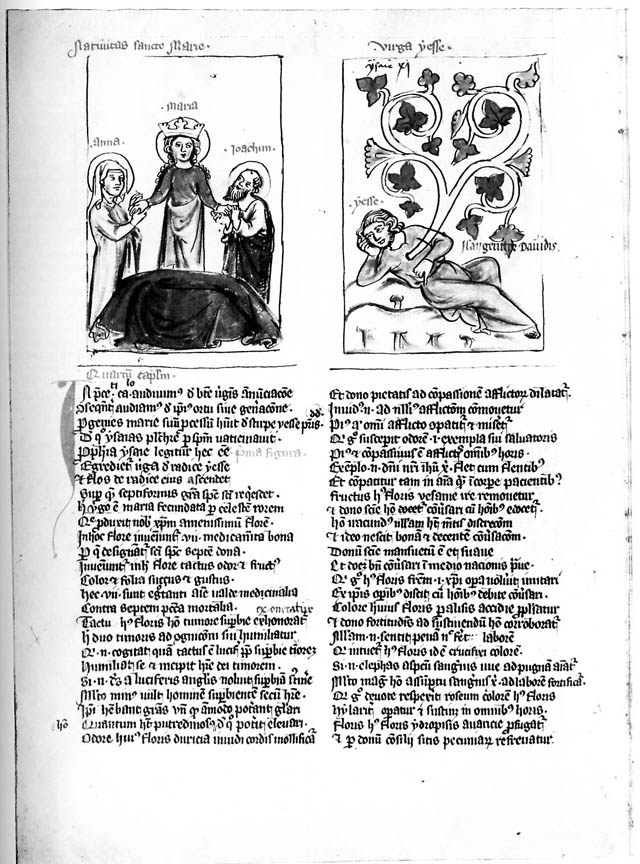

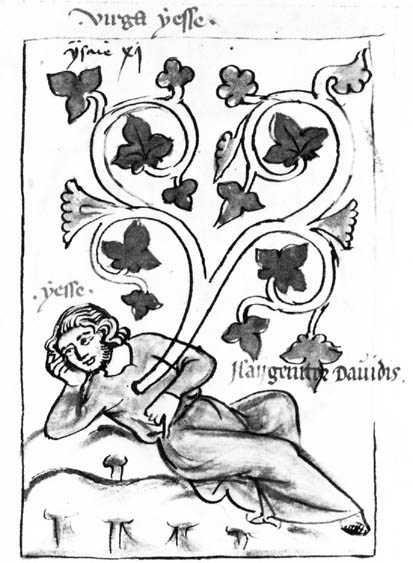

Now that the design and closure method was decided, I turned to the beatification process. As everyone in the SCA is considered a noble rather then a peasant, I felt my shoes should have decorations to emulate my SCA social class. I viewed countless pages of illuminations, photographic images of surviving objects and redrawings of finds such as the scabbards depicted at the end of Knives and Scabbards. My intent was to find period beautifications and patterns that I could then pick from or base my embellishments on. I chose to stay with a floral motif since my patyns these will occasionally be worn with these shoes and they are already completed using such. A leaf and vine pattern shown in Speculum Humanae Salvationis seemed to be the ideal choice to enhance the floral blossoms stamped into my pattens. A pattern very similar to this can also be seen in The Luttrell Psalter.

Speculum Humanae Salvationis,1395

Pierpoint Morgan Library, M.140

Ivy patterns, The Luttrell Psalter, 1345

Detail from Speculum Humanae

Salvationis(upper right image)

Second and third ivy patterns considered, The Luttrell Psalter, 1345

The last choice made was what color to dye this project. Though black seems to be very popular for non-embellished shoes, I did not note a single color to be dominate on adorned ones. I am not personally a fan of bright colors or wearing what we now consider “clashing” colors, despite it being considered fashionable in period to do so. Because of this I went with a basic brown stain to be versatile with all my current garb.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

When adding the 1/8” extra to the pattern for a turn-shoe do not add it to the sole! I was told to “add the extra to your pieces so the shoe is not too small when you flip it right side out”. The speaker presumed I knew not to add the extra to the sole but this being my first pair I had no reason to know. I did not realize the error until I was about 85% through sewing the sole on and could not figure out why my vamp was not matching the sole near the poulaine (in common terms, why the extended toe of the sole didn’t match the portion that covers the top of the foot). The two pieces looked like a pair of scissors with the vamp’s poulaine pointing to the right and the sole’s to the left. I had to pull all my stitching and cut the 1/8” of the parameter of the sole, then start sewing all over again.

Late 14th-century side latched shoe. Detail of poulaine tip

If possible, it must be easier to carve or punch your décor into the vamp and quarters (basically the area from under ankle around heal to other ankle) prior to assembly then it was post assembly. However, I do not know how carved leather will react during the turning process where it is literally soaked with water. After my next pair of shoes I will relate more. Until then, I advise you experiment with scrap. Besides, you can never have too much edge/flesh seam practice, especially edge/flesh butt seams!

Sources:

Shoes and Pattens by Francis Grew & Margrethe de Neergaard (Medieval Finds from Excavations in London #2 by Museum of London)

Textiles and Clothing 1150-1450 by Elisabeth Crowfoot, Frances Pritchard & Kay Staniland (Medieval Finds from Excavations in London #4 by Museum of London)

Gothic and Renaissance Art in Nurembeg 1300-1550 by Mwtropolitan Museum of Art

Illuminated Manuscripts; Treasures of the Pierpoint Morgan Library in New York By Abbeville Press

Manuscript Painting at the Court of France by George Braziller

Knives and Scabbards by J. Cowgill, M. De Neergaard, N. Griffiths, Margrethe De Neergaard, Francis Grew (Medieval Finds from Excavations in London #1 by Museum of London)

What life was Like: In the Age of Chivalry (Medieval Europe AD 800-1500) by Time Life Books

Medieval Costume in England and France; The 13th, 14th and 15th Centuries by Mary G. Houston

The Luttrell Psalter by Janet Backhouse (Medieval Manuscripts in the British Library)

Medieval Manner of Dress by Else Marie Gutarp

Medieval Costume and Fashion by Herbert Norris

Knights by Andrea Hopkins

History of Costume by Milia Davenport

Illuminated leafs from Die Miniaturen der Manesseschen Liederhandschrift (the Manesse Codex) and The Luttrell Psalter.

* Special thanks to Mr. Bechmann (who has personally handled Honnecout’s trebuchet sketch(s) in his studies) for his recommendations on which of his works, with specific pages, would best suit my research goals.