Guest

Author:

August Hunt

August

Hunt, (1960), published his

first short stories in his high school

newspaper, THE WILDCAT WIRES. These were

followed by stories and poems in THE

PHOENIX literary magazine of Clark

Community College, where he received a

writing scholarship. Transferring to THE

EVERGREEN STATE COLLEGE in Olympia, WA,

he continued to publish pieces in local

publications and was awarded the Edith K.

Draham literary prize. A few years after

graduating in 1985 with a degree in

Celtic and Germanic Studies, he published

"The Road of the

Sun: Travels of the Zodiac Twins in Near

Eastern and European Myth".

Magazine contributions include a cover

article on the ancient Sinaguan culture

of the American Southwest for Arizona

Highways. His first novel, "Doomstone",

and the anthology "From Within the

Mist" are

being offered by Double Dragon (ebook and

paperback). August, a member of the

International Arthurian Society, North

American Branch, has most recently had

his book "Shadows in the

Mist: The Life and Death of King Arthur"

accepted for publication by Hayloft

Publishing. Now being written are

"The Cloak of Caswallon", the

first in a series of Arthurian novels

that will go under the general

heading of "The Thirteen Treasures

of Britain", and a work of Celtic

Reconstructionism called "The

Secrets of Avalon: A Dialogue with Merlin".

|

Faces of Arthur is a

part of Vortigern

Studies

|

Faces of Arthur Index

Vortigen Studies Index

|

|

click here

|

The Spirit

of the Wood

August

Hunt

|

WHO

WAS MERLIN – or, rather, what was

Merlin?

This

question has intrigued and vexed countless students of

the Arthurian tradition for centuries. Was he

someone who panicked and ran away from the Battle of

Arfderydd? Who lost his sanity in the battle and

lived like a wild beast in the woods? Had he really

been a great bard of the chieftain Gwenddolau? If

he were a madman, by what mechanism did his insane

utterances become recognized as prophecies? Why was

he also called Llallogan or Llallawg? Why was he

dealt a triple sacrificial death akin to that meted out

to the god Lugh (Welsh Lleu)?

These

questions are important in and of themselves, of course.

But for our purposes they take on a more profound

significance. For by answering them to the best of

our abilities in an objective way, can we say

definitively that originally Merlin had belonged to a

class of druidic priests? Or that he had performed

some vital function for such a priesthood?

In Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the

Kings of Britain, Merlin (= the Welsh Myrddin) is

associated with Amesbury’s Stonehenge on Salisbury

Plain and with Mount Killaraus (= Killare next to the

Hill of Uisneach, the center of Ireland), while in

Geoffrey's Life of Merlin the great sage is placed atop a

mountain in the Scottish Caledonian Wood.

Fragments of the Life of St. Kentigern

tell of a madman/prophet named Lailoken, who is

explicitly identified with Merlin, and who is found on a

"rock" at Mellodonor (modern Molindinar Burn)

within sight of Glasgow and at Drumelzier (modern

Dunmeller) in Scottish Borders. Lailoken is said to have

been buried near Drumelzier.

Before Geoffrey introduced Merlin into the

Arthurian saga by substituting him for Ambrosius of Dinas

Emrys (a hill-fort in Gwynedd, Wales) and Wallop,

Hampshire, the madman/prophet had divided his time

between Carwinelow (the fort of his lord Gwenddolau, near

Longtown in Liddesdale, known now as the Moat of Liddel),

nearby Arthuret (scene of the Battle of Arfderydd, in

which his lord was slain and he went mad), the Lowland

Caledonian Wood with its mountain and the court of King

Rhydderch Hen/Hael. Rhydderch belongs at Dumbarton in

Strathclyde, although Geoffrey makes him a Cumbrian king.

In Geoffrey the Caledonian mountain

remains unnamed. This is unfortunate, in that by finding

this mountain we might learn a great deal more about

Merlin’s identity. And, incidentally, we would

have a much firmer fix on the location of Arthur’s

seventh battle, which occurred in the Caledonian Wood.

Merlin’s Caledonian Wood mountain is

mentioned in one other source: the 13th century

French verse romance by Guillaume Le Clerc entitled Fergus

of Galloway. The Fergus romance is

distinguished by the author’s knowledge of Scottish

geography. To quote from Cedric E. Pickford in Arthurian

Literature in the Middle Ages:

“His [Guillaume's] Scottish geography

is remarkably accurate... In the whole range of Arthurian

romance there is no instance of a more detailed, more

realistic geographical setting.”

The modern translator of Fergus,

the late D.D.R. Owen, has made similar remarks on this

romance. The notes and synopses in his translation also

remind the reader that various elements of the Fergus

mountain episode were adapted from Chretien's Yvain

and Perceval and the Continuations of the latter.

But it remains true that only Fergus

actually names Merlin's mountain and purports to give us

directions on how to get there. The hero Fergus starts

his journey to the mountainn not as Nikolai Tolstoy (in

his The Quest for Merlin) claims at the Moat of

Liddel, where Merlin fought and fled in madness, but at

Liddel Castle at Castleton in Liddesdale. Tolstoy

uses 1) Guillaume's directions and the placement of King

Rhydderch at Dumbarton 2) Merlin's affinity with the stag

in Geoffrey's Life of Merlin 3) the incorrect

identification of Merlin's Galabes spring/s (these are at

Wallop in Hampshire, not in the Scottish Lowlands) and 4)

the great height of the Black Mountain to select Hart

Fell at the head of Annandale as Merlin's mountain.

There are marked problems with each of

these "guidelines" used by Tolstoy. Firstly,

the directions given are incredibly vague and hence can

be used to chart a course from the Moat of Liddel to just

about anywhere:

“[Fergus] comes riding along the edge

of a mighty forest... Fergus comes onto a very wide plain

between two hills. On he rode past hillocks and valleys

until he saw a mountain appear that reached up to the

clouds and supported the entire sky...”

Secondly, Fergus's mountain is given two

names, neither of which match that of Hart Fell:

Noquetran (variants Nouquetran, Noquetrant) and Black

Mountain. The latter is obviously a poetic designation

only, the primary name being Noquetran.

And thirdly, there is no edifice of any

kind atop or on the flanks of Hart Fell which could have

been referred to as ‘Merlin’s Chapel’.

As described, this edifice must be an ancient chambered

cairn. Such monuments are often associated with

Arthurian characters.

The

hill-name Noquetran looks to me like a Norman French

attempt at a Gaelic hill-name, with the first component

being cnoc, English knock, “hill”. As the

French render English bank as banque and check as cheque,

Cnoc/Knock became Noque-.

The

secret to correctly interpreting the –tran component

lies in a closer examination of Professor Owen’s

notes on the Fergus romance. For lines 773-93 he

writes:

This

adventure [of the Noquetran] is largely developed from

elements in C.II [the Second Continuation of

Chretien’s Perceval]. There Perceval fights

and defeats a Black Knight in mysterious circumstances.

Earlier, he had found a fine horn hanging by a sash from

a castle door. On it he gave three great blasts,

whereupon he was challenged by a knight, the horn’s

owner, whose shield was emblazoned with a white lion.

Perceval vanquished this Chevalier du Cor and sent him to

surrender to Arthur. At his castle he learned of a

high mountain, the Mont Dolorous, on whose summit was a

marvellous pillar… fashioned long ago by Merlin.

For

lines 4460 ff, Owen writes:

Mont Dolorous, which also appears in C.II (see

note to II. 773-93 above), is here associated with

Melrose and is probably to be identified with the nearby

Eildon Hills…

In

the Fergus romance, the Noquetran episode comes first.

The horn hangs from a white lion (cf. the lion on the

knight’s shield in the Perceval Continuation)

in the Noquetran chapel, where Merlin had spent many a

year. In front of the chapel is a bronze giant,

apparently a statue, whose arms are broken off by Fergus,

causing the giant’s great bronze hammer to fall to

the ground. Later in the romance, Fergus goes to

the Dolorous Mountain or the Eildons and encounters there

a club-wielding giant in the Castle of the Dark Rock (reminiscent

of the Black Mountain name applied to the Noquetran).

As

it happens, the Eildons are noteworthy for having three

major ancient monuments atop two of their three hills.

On the Eildon North Hill is the largest hill fort in

Scotland, the probable oppidum of the Selgovae tribe. Here

also is a Roman signal station. On Eildon Mid Hill

is a large Bronze Age cairn. The CANMORE database (of

the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical

Monuments of Scotland) has this on the cairn:

This

cairn is situated on the SW flank of Eildon Mid Hill

about 100ft below the summit, at a height of some 1285ft

OD. It has been much robbed and now appears as a low,

irregular mo und of stones, about 50ft in diameter, from

which a few boulders protrude to indicate the possible

former presence of a cist.

Merlin's

Chapel, the Bronze Age Cairn Atop Eildon Mid Hill (Photo

Courtesy John Young)

More

remarkable was the presence below the cairn of the

following (also from CANMORE):

A

group of seven bronze socketed axes, found on the lower

western slopes of Eildon Mid Hill in 1982, is now in the

Royal Museum of Scotland (RMS). More can be found on the

axes in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries

of Scotland, Volume 115 (1985), pp.151-158. An

abstract of this article follows:

A group of bronze socketed axes

from Eildon Mid Hill, near Melrose, Roxburghshire

Brendan O'Connor and Trevor Cowief.

In 1982, a group of seven

socketed axes was found on the lower western slopes of

Eildon Mid Hill, Ettrick and Lauderdale District, Borders

Region. Although recovered from redeposited soil, the

axes probably represent a hoard of the Ewart Park phase

of the late Bronze Age. The find reinforces what appears

to be a significant local concentration of contemporary

metalwork around the Eildon Hills.

CIRCUMSTANCES OF

DISCOVERY

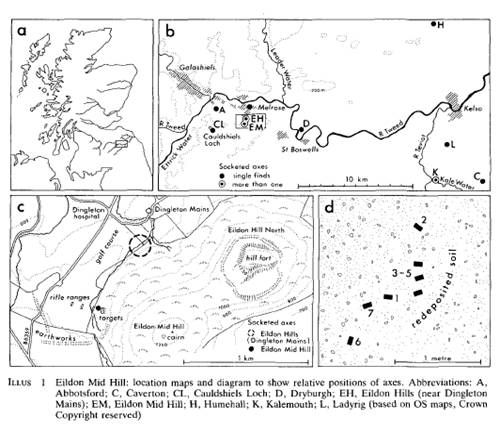

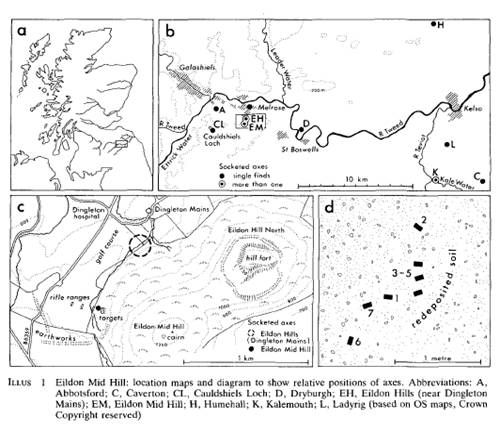

On 9 August 1982, several bronze

socketed axes were discovered by Messrs W and A Wilson (uncle

and nephew) on the margin of the rifle range on the lower

western slope of Eildon Mid Hill, the central and highest

of the three peaks which form one of the most conspicuous

landmarks of the Scottish Border country (illus 1 -2).

They were intending to use Mr William Wilson's metal

detector slightly further uphill in order to search for

shell-cases and cartridges in the area of the targets.

While they were walking up the roughly trodden grassy

path on the northern margin of the range, with their

detector switched on but not consciously in use, their

conversation was interrupted by a signal from the machine.

The tone indicated a non-ferrous metal, and closer

scanning with the detector suggested that there were at

least four soil anomalies within a small area. The

Wilsons decided to investigate the source of these

signals: clearance with a trowel of a small patch of the

tenacious turf revealed, to their surprise, not spent

ammunition but a socketed axe of bronze (catalogue no 7);

a second discrete signal was found to emanate from a

further axe (7) also lying on its own just under

the turf. The source of a third signal was revealed to be

a cluster of three axes lying close together (3-5). Realizing

the growing archaeological significance of their find,

and not wishing to disturb the site further, the Wilsons

responsibly left undisturbed in the ground the sources of

what by then appeared to be two further signals of a

similar nature. They replaced the disturbed turf as best

they could to mask the site, and immediately reported

their discovery to the Ancient Monuments Division of the

Scottish Development Department, one of whose Inspectors,

Dr N Fojut, in turn notified the National Museum. On 17

August, one of the writers (TGC) visited the finders to

inspect the axes already recovered and to view the site

of their discovery, and the following day, he and Mr lan

Scott of the NMAS, with the assistance of Aidan Wilson,

investigated the immediate area of the find (NGR NT

542325).

A

small trench, 2m by 2m, was set out centred on the find-spot

of the cluster of three axes already removed (cf illus 1,

d). Following removal of the coarse turf, the points from

which the five axes had been retrieved became clear:

these showed up as irregular depressions in what appeared

to be the natural subsoil of reddish clayey loam with

plentiful stones (mostly the local felsite). Scanning of

the trench with the detector relocated the positions of

the two signals not investigated by the Wilsons the

previous day. One of these emanated from a slightly

darker patch of humic soil: on removal, this proved

simply to be a deeper pocket of topsoil, occupying a

slightly damper, clayier depression in what seemed once

again to be the natural subsoil. A further socketed axe (6)

lay at an angle on the side of the depression 10-15

cm below the present ground surf ace: perhaps on account

of the damper matrix, the axe was in a noticeably more

corroded condition than the others when found.

Surprisingly, the source of the

final signal appeared to emanate from natural subsoil

with no obvious trace of any feature on its surface.

Removal of a small area of this supposedly natural 'subsoil'

revealed the source of the remaining signal to be a

further axe (2) and threw some light on the context of

the group of axes as a whole. It became clear that this

last axe was not, as first thought, lying in undisturbed

ground, but rather was lying in compacted redeposited

soil apparently occupying the side of a natural gully or

channel in the hillside. In the time available, it was

not possible to excavate the presumed channel nor

determine its width or depth, but the circumstances which

led to the incorporation of redeposited soil in natural

features seem clear enough for the construction of the

rifle range must have involved considerable smoothing out

of the contours and irregularities of the hill-slopes.

Churning up of the ground, the infill of erosional

features such as gullies caused by water run-off, and the

compaction of the area by machines could account for the

formation of the deposit on and in which all seven axes

lay. Indeed, gullies of the type envisaged can be seen

elsewhere on the slopes of the Eildons (see illus 2). The

axes are likely to have been moved bodily in a load of

earth and soil, dumped and then slightly dispersed (axes

2 and 6 were separated by a distance of 1-5 m). Following

the removal of the final two axes, the excavated soil and

turf were replaced and the site restored to its original

appearance as far as possible. Finally the surrounding

area was scanned with the metal detector, but no further

non-ferrous anomalies were noted…

THE ORIGINAL DEPOSITION

OF THE AXES

In view of their discovery in

redeposited soil we cannot be absolutely certain how the

axes were originally deposited. However, their number,

their proximity and their similar condition all suggest

that they came from a hoard, probably close to their

eventual find-spot. Whether the seven axes recovered in

August 1982 comprised the whole hoard remains uncertain.

On the other hand, it is possible, though less likely,

that more than one separate deposit was originally

involved…

I

would see in ‘Noquetran’ or Noquetrant a Gaelic

cnoc or Anglicized ‘knock’ plus one of the

following:

G.

dreann – grief, pain (cf. Irish drean,

sorrow, pain, melancholy)

G.

treana, treannadh – lamentation, wailing

In

other words, Noquetran is merely a Gaelic rendering of

the Old French Mont Dolorous!

The

bronze hammer Fergus causes to be dropped near

Merlin’s Chapel on the Noquetran is a folk memory of

a bronze socketed axe being deposited on the slope below

the Eildon Mid Hill cairn or, more probably, of such an

axe being found on the site prior to Guillaume Le

Clerc’s writing of the Fergus romance.

Merlin’s Noquetran chapel is the Eildon Mid

Hill Bronze Age cairn.

Melrose

Mountain, Black Mountain and Castle of the Dark Rock are

all designations for the Eildons. The hill-name

Eildon is found in 1130 (_Place-Names of Scotland, 3rd

Edition, James Brown Johnston) as Eldunum and in 1150 as

Eldune. While various etymologies have been

proposed, the most commonly favored one is G. aill,

“a rock, cliff”, plus OE dun, “a

hill”. The “Fergus” romance’s

“Castle of the Dark Rock” (Li Chastiaus de la

Roce Bise) may stand for the hill-fort on Eildon North

Hill, with Eildon being perceived as composed of aill,

rock, plus not dun, “hill”, but instead - “OE

dun, a colour partaking of brown and black; ME dunne,

donne, dark-coloured: Ir. Dunn, a dun colour: Wel. Dwn,

dun, swarthy, dusky: Gael. Donn, brown-coloured”

[From Toller’s and Bosworth’s Anglo-Saxon

Dictionary]

So

why were the Eldons identified with the Dolorous Mountain/Noquetran?

The answer may lie in part with Nikolai Tolstoy’s

astute observation that the lion Fergus thinks should be

roaming over the mountain-top, but which he finds inside

the ‘chapel’ is an error or substitution for

the god Lugos (Welsh Lleu, Irish Lugh). In Welsh,

Lleu’s name could sometimes be spelled Llew, and the

latter is the normal spelling for the Welsh word

“lion”. Merlin’s associations with

Lleu will be briefly discussed below. For now,

suffice it to say that the Dolorous Mountain undoubtedly

got its name because Lugos or Lugh was at some point

wrongly linked to Latin lugeo, “to mourn, to lament,

bewail”. Such mistakes in language could

easily have occurred when going from Celtic to Old French.

The

Dolorous Mountain is thus, properly, “Lugos

Mountain”. And the Lugos/Lugh/Lleu mountain is

particular is Eildon Mid Hill, the highest of the Eildons,

with its Bronze Age cairn. Such an

identification of the Dolorous Mountain has implications

for the Dolorous Garde of Lancelot, especially given that

Lancelot himself is a late literary manifestation of the

god Lugh, something first discussed long ago by the noted

Arthurian scholar Roger Sherman Loomis.

We

know of five Lugh forts in Britain, four known and one

unlocated. Of the former there is Dinas Dinlle in

Gwynedd, Loudoun in East Ayreshire, Luguvalium or

Carlisle in Cumbri and Lleuddiniawn or

“Lothian”, land of the Fort of Lugh.

Luguvalium has been interpreted as containing a personal

name *Lugovalos, ‘Lugos-strong’, but I believe

this name is instead a descriptive of the fort itself as

being ‘Strong as Lugh’. Dr. Graham Isaac,

a Celtic language specialist at The National University

of Ireland, Galway, agrees with me that this could well

be the case.

Then

there is the Lugudunum or “Hill-fort of Lugh”

of the Ravenna Cosmography. This place is (see

Rivet and Smith’s “The Place-Names of Roman

Britain”) situated somewhere roughly between Chester-le-Street

and South Shields. The only good candidate would

seem to be Penshaw Hill, which the Brigantes Nation

Website calls “the only triple rampart Iron Age hill-fort

known to exist in the north of England.”

Penshaw Hill is associated with the famous Lambton Worm,

a monster not unlike the two worms or dragons of

Lleu’s hill-fort of Dinas Emrys in Gwynedd, Wales.

The

Eildons are noted for the stories of “Canobie”

or Canonbie Dick and Thomas the Rhymer of Ercildoune.

Canonbie is near to both the Carwinley of Myrddin’s/Merlin’s

lord Gwenddolau and Arthuret Knowes, the scene of the

Battle of Arfderydd in which Myrddin was driven mad.

The 13th century Thomas is credited with

meeting an elf-woman under the Eildon Tree (whose

location is now marked by a stone) and being taken under

the Eildons to the land of Faery. He is also

credited with a prophecy concerning Merlin’s grave

at Drumelzier:

When

Tweed and Powsail meet at Merlin’s grave,

Scotland and England that day ae king shall have.

[According

to P.C. Bartrum in “A Welsh Classical

Dictionary”, under his entry for Llallogan, this

prophecy was first published by Alexander Pennycuick in

1715.]

The

story of Canonbie Dick presents Thomas as a wizard from

past days, and I will quote it in full:

A

long time ago in the Borders Region there lived a Horse

Cowper (trader) called Canobie Dick. He was both admired

and feared for his bold courage and rash temper. One

evening he was riding over Bowden Moor on the West side

of the Eildon Hills. It was very late and the moon was

already high in the night sky.

He had been to market but trade that day had been poor

and he had with him a brace (pair) of horses, which he

had not been able to sell. Suddenly, he saw ahead of him

on the moonlit road, a stranger. The stranger was dressed

in a fashion that had not been seen for many centuries.

The stranger politely asked the price of the horses.

Now Canobie Dick liked to bargain, and was not worried by

the strange man's looks. Why, he would have sold his

horses to the devil himself, and cheated him as well,

given half a chance. They agreed a price which the

stranger promptly paid.

The only puzzle was that the gold coins he used to pay

were as ancient as his dress. They were in the shape of

unicorns and bonnet pieces (Scottish coins from 1400s and

1500s). However, Canobie Dick shrugged his shoulders.

Gold was gold. He smiled to himself, thinking that he

would get a better bargain for the coins than the

stranger had got for the horses.

When the stranger asked if he could meet him again at the

same place, Canobie Dick was happy to agree. But the

stranger had one condition: that he should always come by

night and always alone.

After several more meetings, Canobie Dick became curious

to learn more about his secret buyer. He suggested that 'dry

bargains' were unlucky bargains and that they should seal

the business with a drink at the buyers home.

"You may see my dwelling if you wish," said the

stranger; "but if you lose courage at what you see

there, you will regret it all your life."

Canobie Dick was scornful of the warning, after all he

was well known for his courage and the stranger seemed

harmless enough. The stranger led the way along a narrow

footpath, which led into the hills between the Southern

and central peaks to a place called the Lucken Hare.

Canobie Dick followed but was amazed to see an enormous

entrance into the hillside. He knew the area well but had

never seen before such an opening or heard any mention of

it.

They dismounted and tethered their horses. His guide

stopped and fixed his gaze on Canobie Dick. "You may

still return," he said. Not wanting to be seen as a

coward, Canobie Dick shook his head, squared his

shoulders and followed the man along the passage into a

great hall cut out of the rock.

As they walked, they passed many rows of stables. In

every stall there was a coal black horse, and by every

horse lay a knight in jet black armour, with a drawn

sword in each hand. They were as still as stone, as if

they had been carved from marble.

In the great hall were many burning torches. But their

fiery light only made the hall more gloomy. There was a

strange stillness in the air, like a hot day before a

storm. At last they arrived at the far end of the Hall.

On an antique oak table lay a sword, still sheathed, and

a horn. The stranger revealed that he was Thomas of

Ercildoun (Thomas the Rhymer) the famous prophet who had

disappeared many centuries ago.

Turning to Canobie Dick he said, "It is foretold

that:

He that sounds the horn and draws that sword, shall, if

his heart fails him not, be king over all broad Britain.

But all depends on courage, and whether the sword or horn

is taken first. So speaks the tongue that cannot lie."

The stillness of the air felt heavy. Canobie Dick wanted

to take the sword but he was struck by a supernatural

terror, such as he had never felt before. What, he

thought, would happen if he drew the sword; would such a

daring act annoy the powers of the mountain?

Instead he took the horn and with trembling hands put it

to his lips. He let out a feeble blast that echoed around

the hall. It produced a terrible answer. Thunder rolled

and with a cry and a clash of armour the knights arose

from their slumber and the horses snorted and tossed

their manes.

A dreadful army rose before him. Terrified, Canobie Dick

snatched the sword and tried to free it from its scabbard

(sheath). At this a voice boomed:

"Woe to the Coward, that ever he was born,

Who did not draw the sword before he blew the horn"

Then he heard the fury of a great whirlwind as he was

lifted from his feet and blasted from the cavern. He

tumbled down steep banks of stones until he hit the

ground. Canobie Dick was found the next morning by local

shepherds. He had just enough trembling breath to tell

his fearful tale, before he died.

A

similar story is told of Alderley Edge in Cheshire, only

in that version the wizard is Merlin and the sleeping

knights are King Arthur and his men. My guess

is that in the case of the Canonbie Dick story, Thomas

the Rhymer has taken the place of Merlin. This is

not a new supposition, but combined with my

identification of Myrddin’s Noquetran with Eildon

Mid Hill as the Dolorous Mountain, the argument is

significantly strengthened. For “Fergus”

was written around 1200 AD, while Thomas is thought to

have lived c. 1220-1298. At some point Thomas was

substituted for Merlin at his chapel/cairn on Eildon Mid

Hill.

If I am right and the Eildons are

Merlin’s Mountain at the center of the great

Celyddon Wood, then we can allow for the Celyddon as

being thought of as the ancient woodland which covered

much of the area surrounding the Eildons. When we

combine this with the fact that Merlin was obviously

wandering in the wood in the vicinity of Drumelzier when

he was captured by Meldred, it is fairly obvious that the

Celyddon, which in this context means merely a great

forest of the Scottish Lowlands, extended at least to the

Lammermuir Hills in the north and perhaps as far as the

Cheviots in the east.

As the Roman Dere Street crosses the

Teviot near Jedburgh and the Tweed at Newstead, and four

of Arthur’s other battles were fought on or near

Dere Street, it is likely that Arthur’s Celyddon

Wood battle was fought in part of this ancient woodland

on or near Dere Street somewhere between Teviotdale and

Lauderdale.

Indeed, there were four great ancient

forests surrounding the Eildon Hills: the Jedforest,

whose Capon Tree oak is one of the oldest such trees in

all of Britain; Teviotdale itself, which was covered by

huge oaks and ash trees in the 12th century;

the Ettrick Forest of Selkirkshire; the Lauder Forest, an

immense forested track encompassing Lauderdale that still

existed up until the 17th century.

Apples, or rather crab-apples, the very species of tree

Merlin takes refuge under in the early Welsh poetry, were

also present in this region. The St. Boswell’s Apple

is thought to be 150 years old and is the largest of its

kind in Scotland. Thomas the Rhymer, taken to

Fairyland at the Eildons, is given an apple by the Queen

of Fairy.

We may be able to pinpoint the location of

the Coed Celyddon battle for precisely. Although

Geoffrey of Monmouth has been justly criticized for

producing stories of early British kings rather than

histories, we cannot discount the possibility that at

least occasionally his account of Arthur’s reign may

preserve accurate historical traditions. When he

has Arthur face the Saxons in the Caledonian Wood, he

tells us that

“Arthur… ordered the trees round that part

of the [Caledonian] wood to be cut down and their trunks

to be placed in a circle, so that every way out was

barred to the enemy. “

This circular palisade Arthur constructs

in the Caledonian Wood made me think of the semi-circular

Catrail dyke. To quote the description of the

Catrail from the Royal Commission on the Ancient and

Historical Monuments of Scotland (courtesy Mark Douglas,

Principal Officer for Heritage and Design, Planning and

Economic Development, Scottish Borders Council):

“This is the linear earthwork,

known as the Catrail which runs from Robert’s Linn

to Hosecoteshiel and embraces the entire head of the

Teviot basin from the Slitrig to beyond the Borthwick

Water. It is not continuous, in the sense that is

incorporates streams or woodland, and its engineering, in

short sectors clumsily joined and imperfectly aligned,

stamps it as a product of somewhat inexperienced communal

effort. The date of its construction is doubtful,

though it is certain that it fits only Anglian

territorial dispositions. Oman notes the opinion

that it might mark a political boundary after

Aethelfrith’s victory at Degsastan in 603, and this

is indubitably the earliest possible date for such a work.”

As the date of the construction of

the Catrail is “doubtful”, could we not propose

that it was built slightly earlier, say in the 6th

century, the time of Arthur? The Catrail runs

through what was the great Ettrick Forest, an extensive

woodland which according to Nicola Hunt, Projects Officer

of the Borders Forest Trust (private communication),

‘covered from Dumfriesshire to the Galashiels

area’. Thus this forest was very near to

Merlin’s Eildon Mid Hill.

The derivation of the name Catrail

has been disputed. The most commonly disseminated

etymology is Cymric cad or cat, ‘battle’, plus Cymric

rheil or rhail, wrongly defined as ‘fence’,

probably for a presumed wooden palisade that may have

once existed atop the dyke’s bank.

Unfortunately, as rheil or rhail does not mean

‘fence’. It is ‘rail, track’

and is not attested in Welsh until the 18th century.

According to Professor Richard Coates (Onomastics and

Director of the Bristol Centre for Linguistics at UWE,

and Hon. Director of the Survey of English Place-Names) rheil/rhailis

doubtless a borrowing from English and so Catrail cannot

be derived from Cat + rheil/rhail.

A cad/cat + rhigol (the ‘rhill’

mentioned below), the latter being Welsh for ‘rut,

groove, (long narrow) channel; trench, furrow, ditch,

gutter’, cannot have become Catrail – even

through a process of Anglicization. Rhigolis

pronounced something like “wriggle”.

Again, Professor Coates has assured me that a

hypothetical Cad + rhigolcannot have become Catrail.

This is so despite the attractiveness of “Battle-ditch”

as a meaning for the earthwork’s name.

Dr. Andrew Breeze, the Celtic onomastic expert in Pamplona,

has assured me that rhigol “is unknown before the

sixteenth century and is a loan from English”.

Helen Darling, Part-Time Local

Studies Librarian, Library Headquarters, St. Mary’s

Mill, Selkirk, was kind enough to send me the following

on this feature-name:

“KENNEDY, William Norman:

Remarks on the ancient barrier called "The Catrail",

with plans In Proceedings of the Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland 1857-1860 pp117 - 121

Considerable diversity of

opinion exists as to the derivation of the term, it being

variously stated by different authors. Chalmers

calls it "the dividing fence", or "the

partition of defence"; Jeffrey, "a war fence or

partition - Cat signifying conflict or battle, and Rhail

a fence"; others from Cater a camp, and Rhail a

fence, a dividing fence among the camps; others, again,

from Cud a ditch, and Rhail a fence, the ditch fence or

boundary; while another class call it "the Pictswork

ditch", attributing the formation of it, and all

other ancient artificial remains in the district through

which it passes, to the Picts, - a race regarding

whom very mythical traditions continue to float

about and receive credence; but almost all writers concur

in attributing its formation to the Britons, subsequent

to the withdrawal of the Romans from this country.

CRAIG-BROWN, T. The

History of Selkirkshire or Chronicles of Ettrick Forest.

Vol. I The Shire - The Parishes of Ettrick, Kirkhope,

Yarrow, Roberton, Ashkirk, Innerleithen, Peebles, Stow,

and Galashiels. Edinburgh: David Douglas, 1886, page

47

Concerning the origin of the word

"Catrail" there have been as many different

suggestions as about its purpose:

CHALMERS. - Cad, a striving to keep;

and Rhail, a division. Together - the dividing

fence.

JEFFREY. - Cat, a struggle; and Rhail.

Together - a war-fence.

MACKENZIE. - (Quoted by Gordon).

An old Highlandword signifying wall or ditch of

separation.

VARIOUS. - Cater, a camp; and Rhail.

Cud, a ditch; and Rhail. Cad-rhill - war-trench.

MISS RUSSELL. - Cader (Welsh), a

defence; and Rail.

An amateur philologist has

ventured to suggest the Saxon words camp-trail as at all

events a possible origin, but the probabilities are in

favour of a British or Cymricderivation; and we incline

to cater-rhail, a camp fence. Cater, Celtic for

camp, as in the celebrated Cater-thun, is undoubtedly

derived from the Latin, castra. Until the Romans

came, there was no need for such a word in the native

vocabulary, and it must be kept in mind that the diggers

of the Catrail were Romanised Britons.

That there was along the Catrail

a terrible struggle for supremacy between the Cymriand

the Saxons may be inferred from the frequent occurrence

of names beginning with the word "Cat", or

"Cad", Cymric for battle or conflict. Nor

far from its northern end is Cat-pair, and nearer, Cat-ha(?).

Caddonwe have seen derived from Cad afon, battle river.

Cat Craig is a hill on Tinnis farm in Yarrow, traversed

by the Catrail. A little further up is Catslack,

and there are pools near by known as Cat Holes.

Finally, near the end of the trench is Catlee. It

is necessary, however, to be on one's guard against

etymological inferences, and these names are submitted

with due reserve.”

The noted Scottish place-name expert

Watson said that the Catrail name ‘may be compared

with Powtrail [now Potrail], the name of a head-stream of

Clyde’ whose ‘meaning is obscure’.

As Henry Gough-Cooper of the Scottish Place-Name Society

confirmed, the Pow- of Powtrail is almost certainly Cymric

pwll, ‘pool’, but also ‘stream’.

After noticing on the map that the Powtrail

has many pronounced bends or turns, I would follow

Professor Richard Coates’ (Onomasticsand Director of

the Bristol Centre for Linguistics at UWE, and Hon.

Director of the Survey of English Place-Names) suggestion

of Welsh traill, ‘turn, a turning’, as the

stream’s second component, supplying us with a

meaning of ‘stream that turns’ or the ‘turning

stream’.

There is precedence for connecting traill

with a stream or river-name: Chepstow’s earlier

Welsh name was Ystraigl or Ys-traigl, ‘a turn’,

this being a reference to the bend of the River Wye at

the site of the town.

However, such a derivation for Powtrail

does not help us with the Catrail name.

Henry Gough-Cooper of The Scottish

Place-Name Society has informed me that Alan James

prefers a different etymology for the Powtrail. In

his paper ‘A Cumbric Diaspora?’ (in ‘A

Commodity of Good Names’, ed. Padel and Parsons,

Shaun Tyas 2008), James mentions the Catrail in a

footnote on Powtrail, which he speculates may be Cumbric

“*polter-eil ‘stream of a wattle fence of

woven hedge’: for *eil see ‘The Poems of

Taliesin’, ed. I. Williams (Dublin 1968), pp. 85-6.”

According to Gough-Cooper, *Polter is

stream-naming word found in northern Cumberland, parts of

the Solway basin and south-west Cheviots, e.g. see EPNS

Cumberland I, 8, 24, 62; II, 373; plus Polterkened in the

Lanercost Cartulary. Alan James suggests perhaps *pol +

extension *duvr, the latter being the word for ‘water’.”

One might compare for this last element the river-names Kielder

and Calder, both from Welsh caled, ‘hard’, and dwfr

(OBrit dubro-), ‘water, stream’.

Williams, on the pages cited by James,

says that:

“Eil was used of any sort of construction

involving plaiting, wattling, and

presumably would denote a defensive construction... Cf.

perhaps Irish aile, ‘a fence’…”

The problem with the –ail of

Catrail being the word for ‘fence’ is what to

make of the first component, Catr-.

I would propose that the first

component was derived from Gaelic cathair, 'fort'. Even

though, as Dr. Richard Coates has made clear to me, the

medial th in cathair is silent (cf. Welsh caer, 'fort')

and should not have yielded Catr-, in Highland Scotland

we do find the Brown and White Caterthun (cathair + dun)

forts. If cathair could become cater in these names,

certainly it could have become the Catr- of Catrail.

But if the Catrail is the ‘Fort-fence’,

what fort are we talking about?

John Barber, Elaine Lawes-Martay and

Jeremy Milln (in “The Linear Earthworks of Southern

Scotland; Survey and Classification”, Transactions

of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and

Antiquarian Society, Series III, Volume LXXIII, 1999),

summarize their study of the Catrail thusly, bringing the

dyke into connection with the fort next to Merlin’s Eildon

Mid Hill, the center of the Celyddon/Caledonian Wood:

“The natural segmentation

of the Scottish landscape into separate territories may

also account for the relative absence of sites used as

local-administration boundaries. These administrative

units are usually fairly clearly defined by the nature of

the terrain and separated from each other by distinct,

natural features, such as ranges of hills of mountains.

This factor may also account for the paucity of lengthy

earthworks. Of those examined in this study only the

Catrail seems likely to have functioned as a large scale

territorial boundary. In association with other natural

features, it may have functioned in respect of the

hillfort of North Eildon Hill in the same role as the

earthwork called ‘The Dorsey’ seems to have

functioned in respect of the royal site of Eamhain Macha

(Lynn 1981). The discovery that the line of the Dorsey is

continued across an apparent gap, once bogland, by a

wooden palisade perhaps points to new avenues of approach

to similar areas on the Catrail.”

In the same Transaction of the

DGNHAS the Catrail is described in detail:

| The Catrail by Jeremy Milln Prior to this

report, as many as fifty writers have mentioned

the Catrail, the most recent being the RCAHMS

which, in the autumn of 1945, carried out the

only previous systematic survey (RCAHMS, 1956).

All those portions given credence by RCAHMS (and

many other earthworks which have on occasion been

hypothesized as forming part of the Catrail),

were re-surveyed by the CEU in 1984. The major

part of the earthwork examined in 1945 had

survived, but increasing land-use pressure includingforestry,

drainage and cultivation, has been responsible

for a rapid deterioration in its overall

condition. The erroneous but popular concept of

an earthwork extending for some 86 kmin a broad

arc from Peel Fell on the border with

Northumberland to Torwoodlee, north of Galashiels,

was first expressed in the Itinerarium Septentrionale

(Gordon 1726, 102-4). Chalmers (1886, 240-3)

regarded it as having formed a frontier between

Romanized Britons in the west and the Saxons in

the east, running from the Forth to the Tyne, and

including the Northumbrian Black Dyke. Murray (1864,

37-8) seems to have been the first to point out

that the Catrail incorporates two separate and

distinct earthworks. Craw’s plan of 1924 (Craw

1924, 42) shows one segment running from Roberts

Linn to Hoscoteor possibly Clearburn, and a

second, the Pictswork, extending from LinglieHill

to Torwoodlee near Galashiels.Some succeeding

writers were prepared to accept the curtailed

Catrail, but Smail (1879) and particularly Lynn (1898)

adhered in detail to the older theory. Lynn’s

account is the more meticulous, but he was unable

to distinguish between the true linear earthwork

and the intermittent remains of old 80 GAZETTEER

OF GROUP 1 SITES roads and field-boundaries; most

notable is his misinterpretation of branches of

the Minchmoor Roadin Selkirkshire, which have

since been clarified (Inglis 1924, 205-6). The

RCAHMS account of the course of the Catrail (1956,

479-83), as well as for the Pictswork (1957, Nos

126-7), is questionable only in matters of minor

detail. The course of the Catrail is shown in Fig.

3. The following account examines it sector by

sector beginning at its alleged origin at Peel

Fell, on the border (Gordon 1726, 102). Earlier

reports suggest thatthe Catrail ran for about 9

kmfrom Peel Fell to Roberts Linn via the Wormscleuch,

Liddel, Dawston and Cliffhopevalleys. The only

definite linear earthwork now visible on this

line is an indeterminate fragment at CaddrounburnCulvert

(152). As the RCAHMS survey points out (1956, 480),

the topography of the steep-sided Roberts Linn

forms a convenient natural break to its course

here.

With the exception of a 350 m gap to the west of

the Langside Burn (281) the earthwork from

Roberts Linn is continuous as far as the head of Barny

Sike(282) and it is only beyond this point that

uncertainty occurs. Smail (1879, 113), following

Gordon and Chalmers, asserts that it crossed WhitehillLower

to the north of the enclosure; there is indeed a

linear earthwork at this height (201), but no

evidence of a connection past Pyot’sNest (NT

4817 0530). Furthermore, this earthwork is

markedly off line with the bank on the south side

of the ditch. This suggests that it is one of a

number of linear outworks delimiting the ground

around Pyots’ Nest fort on its landward side

where it is overlooked by Whitehill. A short

length of linear outwork passing close to the

south-west side of the enclosure at the Dod (NT

4727 0602) is aligned on 201 and could perhaps be

considered part of the Catrail (Ian Smith, pers comm),

but it is isolated and nowhere recognized in the

literature. Elsewhere, the line of the Catrail

incorporates streams, suggesting that the course

from the head of Barny Sikemight be along Barny Sikeitself

and the DodBurn. The next section would thus seem

to be 283 and, though this earthwork is

discontinuous, for the most part its character is

similar to that recognized elsewhere. RCAHMS (1956,

No 481) suggests its sudden extinction above Priesthaughmight

be explained by an area of valley side scrub

carrying the work to the top of 284, 900 mto the

north. It is debatable whether the short stretch

of bank from Peel Brae to the Dod-Priesthaughroad

continued west across the road to the earthwork

on the Allan Water; though Lynndoes record a cropmarkin

the cultivated field (Lynn 1898, 79). The

connection with the Allan Water, which almost

certainly maintained the line to Doecleuch, might

alternatively be made by a 300 mlength of

earthwork, consisting of a ploughed-down bank,

running along the valley floor north of the farm

at Priesthaugh (288). The next surviving fragment,

285, lies on the north-west slopes of DoecleuchHill,

and continues the RCAHMS Inventory entry (1956,

No 481), which cites a point (NT 460 061) on the

south-east of that hill. The area is disturbed by

rig and furrow and it was not discernable in the

present survey. It is possible however,that the

work ran from the steep lip of Doecleuchat NT

4609 0634 to join the truncated end of 285 at the

DodBurn-TeindsideRoadand part of the line of this

is preserved by an old footpath. 285 may have

continued as far as Chapel Cleuch, just south-west

of Old Northhouse (it is marked on a plan of 1857

inthe library of the Society of Antiquaries of

Scotland), but the area is now marshy and no

earthwork can be distinguished. The course of the

Catrail, as far as the Muselee Burn, continued by

the Northhouse and TeindsideBurns and 286, has

never been disputed. Lynn (1898, 73) claimed that

a short length was to be seen on the west side of

the MuseleeBurn opposite the north-west end of

286, but he seems to have been misled by a track.

By implication, it ran north/north-west across

the rough pasture to pass close by the west side

of the enclosed earthwork at Broadlee. As the

latter certainly belongs to the enclosure, there

can be no doubt that the work was continued to

the Borthwickvalley by the MuseleeBurn. THE

LINEAR EARTHWORKS OF SOUTHERN SCOTLAND 81 Many

writers (Smail 1879, 113; Lynn 1898, 78; Craw

1924, 42) assume that 134 continued the earthwork

from the head of a dry gully above the Hoscotepolicies.

The RCAHMS rightly recognizes this as a work of a

completely different trend and follows Kennedy (1860,

121) in accepting 287 as bridging the hiatus

between the south end of this earthwork and the HoscoteBurn,

with a course meeting the burn at NT 3845 1115.

The case for accepting 287, though, is not proven,

as this earthwork shows evidence of recent

modification, perhaps as a field boundary, and

the characteristics of the Catrail, if they

existed, are obscured. Lynn’s idea of a

‘branch line’ continuing north-west

past Hoscoteshielto include 12 should therefore

be dismissed. Murray’s theory (1864, 37)

should also be mentioned here, namely that the

work terminated not on the Dean Burn but on the

Clear Burn. Two earthworks, Quarry Rig (14) and

Clear Burn (10), carry on the line from near the

upper end of the HoscoteBurn to a point just

above the head of Buck CleuchLinn. The remains of

both earthworks are badly damaged by drainage and

afforestation, but their alignment and character

are similar to that of the Catrail proper (see

below). The sectors of the ‘core

monument’, to which the name Catrail has

been restrictedare as follows - 281 Catrail (NT

5385 0262 to NT 5005 0365; 259-322 m OD; 4140 m)

Roberts Linn - LangsideBurn The largest

continuous portion of the true Catrail. Runs west

from the mouth of Roberts Linn across the north

ridge of Leap Hill to the west/north-west as far

as the Langside Burn, a distance of c 4 km.

Crosses 11 small burns flowing north into the Slitrig

Water and the spurs and ridges between,

irrespective of contour. Clearly visible, but in

poor condition.On steep slopes its character has

been degraded by natural surface drainage and on

the more level ridge tops it has been obscured by

the accumulation of peat. Consists of a low,

rounded bank with a ditch, generally the more

noticeable feature, on the uphill side.Today it

rarely exceeds an overall width of 6 mand height

of 0.5 m. Peat accumulation may account for some

of the considerable diminution since it was first

recorded 250 years ago. RCAHMS notes a

counterscarp bank in one place which has vanished

since 1945, but generally the work is not badly

affected by human activity. Entire portion now

covered by plantations within which it occupies a

generous corridor, although a number of narrow

surface drains cut the work, but vulnerable to

damage in the course of thinning and felling and

by heavy machinery using the break in which it

lies. 282 Catrail (NT 4975 0405 to NT 4815 0502;

30-451 mOD; 1970 m) Foot of the Pike - Barny SikeThis

earthwork, visually the most impressive surviving

portion of the Catrail proper, extends from the

upper limit of once cultivated land to the west

of the LangsideBurn. Runs steeply across the

ridge of the Pike, across the PenchriseBurn and a

further, lower ridge of high ground to terminate

at the head of the Barny Sike, a feeder stream of

the DodBurn. Largely as described by RCAHMS with

a definite ditch traceable over most of its

course, flanked on the north/north-east by a main

bank and on the south/south-west by a slighter

counterscarp bank. It is obscured by peat moss on

the more level ground at the summit of the Pike,

in the valley of the PenchriseBurn, and on the

moor to the west of the modern track from Peelbraehopeto

Stobs, but the general character of the work is

clear, with overall dimensions of 5.5-6.5 mwide

and 0.7-1.2 m high. Between the top of the Pike

and the modern track the earthwork is followed

closely, and at points crossed by, the present

boundary between the lands of PenchriseFarm and

those of the Forestry Commission. The

latter’s land was ploughed and planted in

1981 and it is evident that despite this portion

being scheduled, it has been badly disfigured, particularilyin

the area near the PenchriseBurn. 82 GAZETTEER OF

GROUP 1 SITES 283 Catrail (NT 4825 0575 to NT

4770 0590; 305-366 m OD; 480 m) Head of dry

hollow west of the DodBurn - Shoulder of Peel

Brae The position of this earthwork is somewhat

dislocated from the Catrail, but similarities in

its course and character allowed its acceptance

by the RCAHMS. Running from the head of a dry

linear gully to the west of the Dod Burn, it

ascends the ridge of Gray Coat along a slightly

sinuous course, is crossed by the property

boundary along the spine of that ridge and

finishes abruptly on the shoulder overlooking the

Allan valley. Consists of a ditch with a bank to

the north.RCAHMS suggests that its segmented

appearance is due to its construction in short

sections, however, the occurrence of localized

patches of moss and the considerable disturbance

wrought by an old track, the ‘Thieves’

Road’, and banks associated with 185 render

this observation most uncertain. 284 Catrail (NT

4675 0535 to NT 4630 0440; 259 m OD; 90 m) Foot

of Peel Brae - Modern Dod/Priesthaughroad

Consists of a broad low bank some 4 macross. No

ditch. Runs from near the foot of the steep Peel

Brae ridge where it has an abrupt, round terminus,

to the Dod/Priesthaugh road, by which it is

clearly cut. The RCAHMS has followed the received

opinion that it is part of the Catrail, although

the differences in form suggest that its position

and alignment may well be fortuitous. Abutted

near its upper end by a length of eroded head-dyke

running south. 285 Catrail (NT 4561 0672 to NT

4535 0672; 256-305 m OD; 340 m) DoecleuchHill/Gray

Hill - Old NorthhouseSwamp Visible on the west

side of the Teindside-Priesthaughroad between DoecleuchHill

and Grey Hill. Runs west, down to the edge of the

boggy ground south-east of Old Northhouse. Consists

of a ditch with a bank on the north and a slight

counterscarp bank to the south. Best-preserved at

east end near the road.There is a reduction in

the vertical dimension of both themainbank and

ditch to the west end, with the lowest 20 mmuch

modified by run-off and artificial drainage. Both

sides currently being eroded by ploughing.286

Catrail (NT 4133 0960 to NT 4047 1038; 271-297 m

OD; 1140 m) TeindsideBurn - MuseleeBurn Visible

in the moss at the head of the TeindsideBurn as a

large ditch, probably enlarged by seasonal

erosion. Runs north-west to the parish boundary

by which time the ditch is 0.35 mdeep: the main

bank to the north-east, 2.5 mwide and 0.25 mhigh,

and a counterscarp bank to the south-west, 1.6 mwide

and 0.1 mhigh. Easily traced to its termination

on the MuseleeBurn, with dimensions similar to

those above, though the counterscarp bank is

discontinuous. Towards the north end where the

work, unusually, is overlooked by high ground to

the north-east, the main bank changes to the

south-west side. Broken in four places by droving

tracks. Has suffered erosion from livestock.Obscured

by an area of peat moss just north-west of the

parish boundary. 287 Catrail (NT 3890 1160 to NT

3735 1135; 259-283 m OD; 520 m) North-east corner

cultivated lands of Girnwood - Tributary of the

Dean Burn Commences at the track which passes to

the north of the cultivated lands of Girnwoodand

borders a new conifer plantation. Runs north/north-west

across two small tributary streams of the Dean

Burn to end abruptly at the bank of a third.RCAHMS

regards only the southern two-thirds of this

length to THE LINEAR EARTHWORKS OF SOUTHERN

SCOTLAND 83 be part of the Catrail (NT 3890 1160

- NT 3796 1216) dismissing the remainder as being

‘probably an agricultural division’.

However, the line is unbroken and on the same

alignment, suggesting a common usage if not

origin. The ditch is 2.5 mwide, very shallow, and

with a bank on the east/north-east side and in

the former section only is an exiguous bank. The

main bank at some 0.8 mis surprisingly high,

which suggests that if this earthwork belongs to

the Catrail it has been raised and the ditch

widened, giving credence to the RCAHMS suggestion

that it was used as an agricultural division; the

current boundary, a stone wall, runs alongside.

Much of the earthwork now runs within a young

conifer plantation and the drainage ditches

associated with this development cut it in a

number of places. 288 Possibly Catrail: Priesthaugh

(NT 4646 0480 to NT 4660 0510; 219-223 mOD; 300 m)

Runs from the edge of a small copse of deciduous

trees across the valley floor north of PriesthaughFarm

to a thicket. Consists of a low, rounded bank,

much reduced by cultivation, and a very slight

ditch on its east side.The bank is nowhere

greater than 0.3 mhigh, its cropmarkbeing some 3

mwide. Runs along a gap in the line of the

Catrail, but it may simply represent an old

drainage dyke. 289 Possibly Catrail: DoecleuchHill

(NT 4562 0640 to NT 4561 0672; 305-312 mOD; 310 m)

Runs from the south end of Gray Hill along the

ridge of DoecleuchHill just east of its crest,

through a mature conifer plantation towards the

middle of a large field of improved pasture.

South end severely damaged by cultivation. North

end overrides the filled ditch of the Catrail (285)

and abuts its bank close to the modern road

between Teindside and Dod.

Where both are still visible, the bank (2 mby 0.25

m) lies on the east side of the ditch (1.5 by 0.3

m). Badly damaged by ploughing and plantation

trenches, the only well-preserved section being

the 15 m at the north end used as a field

boundary at present.Probably an early

agricultural dyke and not part of the Catrail.

|

THE NAME MYRDDIN

The best derivation for the name Myrddin

has been proposed by Dr. G. R. Isaac of The National

University of Ireland, Galway:

"The attested name MYRDDIN reflects

an earlier, not directly attested

*MYR-DDYN, with the second element DYN 'man, person', and

the first element

MYR- which is found in the name of the Old Irish goddess-type

figure

MORRIGAIN (who also prophesies), and in English night-MARE,

and also in

several Slavic words (see Indogermanisches etymologisches

Woerterbuch p.

736). The basic meaning was 'supernatural being, elf,

goblin, phantom' or the like. So *MYRDDYN was

originally something like 'elf-man'. Note his

patronymicon MYRDDYN FAB MORFRYN 'elf-man son of elf-hill'.

"The form Mórrígain with long vowel

in the first syllable, so 'Great Queen',

occurs from the Middle Irish period on, due to folk

etymology, as we call

it (the alteration of a form due to the mistaken belief

in a false

etymology). T. F. O'Rahilly thought this was the best

form, and enshrined

it in his EARLY IRISH HISTORY AND MYTHOLOGY, followed by

some later

commentators. However, O'Rahilly is no reliable source

for linguistic

analysis, and in this case, he is certainly wrong. As

Thurneysen had

already demonstrated in his DIE IRISCHE HELDEN- UND

KÖNIGSAGE, the form with long first vowel is late, and

the earlier, correcter, form is

Morrígain with a short vowel in the first syllable,

which cannot be

connected with the adjective mór 'great' which has a

long vowel (and of

which the earlier form is már in any case)."

This Myr-ddyn > Myrddin is a much more

satisfactory explanation than the previously offered

theory that Myrddin was derived from the city name of

Carmarthen, ancient Caerfyrddin, Roman Moridunum. This

last notion derives from the fanciful HISTORY OF THE

KINGS OF BRITAIN by Geoffrey of Monmouth. In this source,

Myrddin is found as a boy at Carmarthen. The whole story

is Geoffrey’s alteration of Nennius’s tale of

the boy Ambrosius being found at Campus Elleti in

Glamorgan.

THE CELYDDON WOOD AS THE LAND OF

SPIRITS

The ancient Classical writer Procopius (in

his HISTORY OF THE WARS, VIII, XX. 42-48) said:

“Now in this island of Britain

the men of ancient times built a long wall, cutting off a

large part of it; and the climate and the soil and

everything else is not alike on the two sides of it. For

to the south of the wall there is a salubrious air,

changing with the seasons, being moderately warm in

summer and cool in winter… But on the north side

everything is the reverse of this, so that it is actually

impossible for a man to survive there even a half-hour,

but countless snakes and serpents and every other kind of

wild creature occupy this area as their own. And,

strangest of all, the inhabitants say that if a man

crosses this wall and goes to the other side, he dies

straightway… They say, then, that the souls of men

who die are always conveyed to this place.”

From the Welsh poem "The Dialogue of

Myrddin and Taliesin" (BLACK BOOK OF CARMARTHEN), we

learn that at Myrddin’s Battle of Arfderydd:

Seven score chieftains became gwyllon

;

In the Wood of Celyddon they died.

Gwyllon or "Wild Ones" is a word

deriving from gwyllt, "wild". The Welsh epithet

for Myrddin is, of couse, Gwyllt. Myrddin Gwyllt is

Myrddin "the Wild".

But as Tolstoy pointed out, there is

something odd about these two lines. The gwyllon or

“Wild Ones” are equated with the

warriors who died in the battle! The word

“died” in the poem’s second line is Middle

Welsh daruuanan. Modern Welsh has darfyddaf or

darfod, which according to the authoritative

“Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru” (A Dictionary of

the Welsh Language) has the following meanings:

To come to an end, end, conclude, finish,

complete, terminate, cease; expire, die, languish, weaken,

fail, fade, decline, perish

There is thus no ambiguity in the poetic

passage we are considering. The warriors who became

“Wild Ones” did not simply “go away”

or “disappear” – they died.

In this context, then, to become gwyllon means to become

a roving spirit that has left its battle-slain body

behind. To exist as a “Wild One” is to

exist in spirit-form after the death of the body.

The Christian medieval mind either could

not accept this notion of wandering spirits or, just as

likely, misunderstood it. The gwyllon were

transformed into living madmen who leapt or

flitted about the forest much as did their Irish

counterpart, Suibhne Geilt.

In another Myrddin poem, "Greetings"

(BLACK BOOK OF CARMARTHEN), we are told by Myrddin

himself:

The hwimleian speaks to me strange

tidings,

And I prophesy a summer of strife.

Hwimleian or "Grey Wanderer" is

yet another word for a spirit or spectre.

Myrddin "the Wild" was thus the

soul of a dead man, wondering the woods of Celyddon. We

must presume that it was believed that certain

individuals with necromantic skills could communicate

with or perhaps even channel such spirits and thus

extract from them information only available to the dead,

e.g. prophecies.

Difficult as it is for us to believe in

this modern age, ancestral spirits were once

worshipped or placated with offerings. The 'Dis

Manibus' or "For the Divine Spirits of the Dead"

was a common heading for Roman period memorial stones. Morddyn

the "Elf-Man" may have been such a spirit of

the dead.

In the case of Merlin, then, we have a

warrior-bard who is slain in battle at Arfderydd.

His spirit wandered the Lowland Scottish forest, but had

its proper home atop the Lugh Mountain of Eildon Mid Hill.

There, in “Merlin’s Chapel”, the Bronze

Age cairn whose interior symbolized the Otherworld/Underworld

and which was also a portal to the Otherworld, the

spirits of the dead who had worshipped Lugh in life

congregated. Although thanks to Geoffrey of

Monmouth and others Myrddin/Merlin came to be conflated

with Lugh or perhaps seen as a human avatar of the god,

the most judicious interpretation of the early sources

does not warrant such an identification of ghostly

warrior-bard with divine entity.

LAILOKEN

We need now address the problem of Myrddin's

identification with the madman Lailoken, W. Llallogan or

Llallawc. In his edition of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Life

of Merlin, Basil Clarke proposes that Myrddin was

originally a certain Llallawg or Llallogan who went mad

at Arfderydd. Lailoken/Llallogan, suggests Clarke, may

derive from a placename similar to the Gaulish village

Laliacensis, which was named after the family of Lollius

Urbicus, a second century Governor of Britain.

However, the word llallawc/llallogan (linked

to W. llall, "other", a reduplicated form of

ail/eil) is used in Welsh poetry, where it denotes

something like "lord" or "friend" or

"dear friend". W.F. Skene, in his The Four

Ancient Books of Wales, translates the word as "twin

brother". Ifor Williams translates it as "friend"

in The Poems of Llywarch Hen. Egerton Phillimore and A.O.H.

Jarmon make a case for it being a true personal name.

The crux of the issue is found in the

Welsh poem, "The Prophecy of Myrddin and Gwenddydd,

His Sister". There Gwenddydd addresses her brother

Myrddin as both Llallogan (once) and Llallawc (several

times). The question then is: are we to see Llallogan/Llallawc

as merely a term of endearment applied to Myrddin or as a

separate person with whom Myrddin was identified?

The MS. Cotton Titus A. XIX contains the

tales of "Kentigern and Lailoken" and "Meldred

and Lailoken". Jocelyn's 12th century

Life of St. Kentigern also mentions Lailoken in its last

chapter. In both, Lailoken is identified with Merlin.

In the story of Meldred and Lailoken,

Merlin suffers a triple death at the hands of Meldred's

shepherds. The triple death is a motif found in

Celtic literature and was a special kind of death meted

out to kings, heroes and gods alike. It is, in

essence, a form a human sacrifice, made sacred by the use

of three simultaneous methods of killing. In their

book The Life and Death of a Druid Prince, Anne

Ross and Don Robins hypothesize that each method of

killing was sacred to a specific god. The three

Celtic divinities in question have been tentatively

identified with Taranis the thunder god, Esus the lord

and master and Teutates, the overall god of the people.

Doubtless there were regional counterparts to these

deities.

Nikolai Tolstoy used the example of

Lailoken's triple death to more closely link Merlin with

the god Lleu/Lugh, as Lleu in Welsh tradition also

suffers a triple death.

The true importance of Merlin's triple

death on the Tweed near the Dunmeller of Meldred has been

overlooked, however. For it clearly demonstrates

that by the time of the composition of the Life of St.

Kentigern, any memory of the poetic device which

employed a state of madness to represent a post-death

spectral existence had been lost. No one understood

any longer that Merlin or, rather, Myrddin, had died at

the Battle of Arfderydd. And because his madness

was taken literally, a story was concocted which sought

to demonstrate his divine nature by making him the victim

of a three-fold human sacrifice.

That such a form of human sacrifice was

actually practiced has been proven by examination of the

Lindow Man, who was struck in the head by an axe, choked

with a garrote and drowned in a pool (see again The

Life and Death of a Druid Prince). By

undergoing such a sacred killing, the Lindow Man was

acting the role of a god like Lleu. And by acting

such a role, he became the god – a sun god who was

seasonally killed and reborn.

The corollary of the three-fold death

was, of course, resurrection. The god Lleu, who in

death is represented as a Jupiter-eagle in an

oak tree, was brought back to life by Gwyddion. The

Lindow Man as Lleu or a similar sun god, by

dying, helped insure the seasonal rebirth of the sun god.

For as the sun died each year, so was it reborn.

There cannot be life without death.

Merlin under his nickname Llalogan thus

becomes the god in death. But in life, he was a

warrior serving his lord Gwenddolau, who also perished at

Arfderydd.

The model for Myrddin’s/Lailoken’s

death at Dunmeller may have been borrowed from another

“elf” figure. In Welsh tradition we find

a character called Gyrthmwl Wledig (variants Gwerthmwl,

Gwrthmwl, etc.). In Triad 1, he is mentioned as

Chief Elder of Penrhyn Rhionydd in the North. Arthur is

Chief Prince of the same place, while Cynderyn Garthwys [St.

Kentigern] is the Chief Bishop. We have seen above that

Lailoken was brought into connection with Kentigern.

In Triad 44, immediately after mention of

the Arfderydd battle is made, Gyrthmwl's sons are said to

have ridden onto Allt or Rhiw Faelawr or Faelwr in

Ceredigion. This is the site of the fort known as Dinas

Maelawr (modern Pendinas), the home of the legendary

Maelor Gawr or Maelor "the Giant". Dinas

Maelawr is also called Castell Maylor and was built upon

a high hill or ridge beside the river Ystwyth.

Gyrthmwl’s sons ride up the hill to avenge their

father, whom Maelor is said to have killed.

We have seen that the Life of St.

Kentigern places Merlin at Dunmeller, modern

Drumelzier, on the Tweed. It is here that he is captured

by the chieftain of Dunmeller, Meldred (cf. Maldred, the

name of the early 11th century Scottish Lord

of Carlisle and Allerdale in Cumbria), and it is

Meldred’s shepherds who kill him.

The chieftain Gyrthmwl in Triad 63 is

referred to as "Ellyll Gyrthmwl Wledig", the

word ellyll meaning "spirit, phantom, ghost, goblin,

elf, fairy". In her note to Triad 63, Rachel

Bromwich suggests that the word ellyll in this context

may be related to that of the Gwyllt epithet used for

Myrddin and the Irish Geilt epithet used for the madman

Suibhne.

To quote the relevant Triad in full:

Tri Tharv Ellyll Ynys Brydein:

Ellyll Gvidawl

Ac Ellyll Llyr Marini

Ac Ellyll Gyrthmvl Wledic

Three Bull-Spectres of the Island of

Britain:

The Spectre of Gwidawl

The Spectre of Llyr Marini

And the Spectre of Gyrthmwl Wledig.

Ellyll is cognate with Irish Ailill, a

personal name with the same meaning. Rather

remarkably, the best etymology for ellyll and Ailill is

yet another reduplicated form of ail/eil,

“other”. To quote from Professor Daniel

Melia of the University of California, Berkeley (personal

communication):

“I’m citing CELTICA3, 1956,

which reads as follows in its entirety:

‘The contracted form of Ailill gen.

Ailella in all the manuscripts of the genealogies which I

have read (Rawl. B 502; Laud 610 ; LL ; BB; Lec. ; H 2.7)

is always Aill-, Aill-a. These contractions are

quite abnormal.

Ailill is without a doubt cognate [1]

with Welsh ellyll "ghost, elf, etc." and this

suggests that the older form of the name was Aillill

which became Ailill with the same kind of dissimilation

we find in cenand < cenn-fhind and menand < menn-fhind.

[2]

Aill-, Aill-a would be perfectly

normal contracted forms of Aillill, Aillilla and probably

go back to a time when these were the current forms.

[1] Unless the absence of syncope points to its being

borrowed; but in that case we should expect it to be

indeclinable.

[2] Mennand Wb. 9 c 34 may be a pre-dissimilation form.

‘

The Geiriadur Prifysgol Cymru agrees with this meaning (perhaps

influenced by O'Brien's article, however.) They see

a connection, as do you, with a reduplicated form of

proto-celtic *allo- "other" as in the Gaulish

tribal name "Allobroges" < *allo "other"

+ bro- "border" -> "country".

The Wurzburg glosses on the Pauline Epistles (Wb.) date

from ~600-~750, so the form "Aillill" would

presumably, by O'Brien's argument, have still been

current, at least amongst literate intellectuals, in that

period.”.

Dr. Ranko Matasovic of “The

Etymological Lexicon of Proto-Celtic” (again via

private correspondence) says

“Welsh ellyll is indeed cognate with

Mir. Ailill, but these names cannot be related to English

elf, which is frfom Germanic *albiyo-. It is

certainly possible that these words contain the stem *al-

(actually *h2el-, in a more modern notation), the plain

pronominal stem that meant ‘other, different’ (Lat.

alius, Gr. allos, etc.). I would add that Alladhan,

the name given to Llallogan in the Irish Suibhne Geilt

story, would appear to be from Irish allaid,

‘wild’. The most likely etymology for

allaid is the same al- root, as an ‘Other’ is

someone who lived beyond the civilized world and was

hence barbarous or ‘wild’, a stranger or

foreigner or an enemy, i.e. someone deemed dangerous

because he did not belong to one’s native land. The

evolution of meaning would be similar to the development

from Latin silvaticus, ‘belonging to woods’ to

French sauvage.”

Dr. Graham Isaac of The National

University of Ireland, Galway, and Professor of Celtic

Thomas Charles-Edwards of Jesus College, Oxford, both

agree with this derivation for ellyll/Ailill.

In my article Camelot and Other

Arthurian Centres (Vortigern Studies Website), I

showed how Camelot derives via the Old French from an

earlier Romano-British Campus Alletio. Alletio is

the name of a god whose name contains the same ail/eil

root. Anne Ross has suggested Alletio may,

therefore, be the ‘God of the Otherworld’.

If so, it is rather remarkable that this divine name

would appear to be similar is not identical in meaning

with both Llallogan/Llallawg and ellyll/Ailill (and with

Irish Alladhan; see below).

The first version of the Triad 44 in

Peniarth MS. 27 adds that a giant Maelwr was slain in his

fort by Gyrthmwl's sons in revenge for the murder of

their father. Lailoken, as already mentioned, is killed

by the shepherds of Dunmeller. Gyrthmwl, given that

Penrhyn Rhionydd has been very plausibly identified with

the Rhinns of Galloway (see Bromwich's note to Triad 1),

looks to be the 8th century Bishop of Whithorn,

Frithuwald.

The discrepancy in date between Frithuwald

and Kentigern (d. 603) is probably due to Nennius's

statement that the Bernician chieftain "Friodo(l)guald",

i.e. Frithuwald, was ruling in the last quarter of the 6th

century. This Friodo(l)guald is mentioned along with

Deoric son of Ida, Hussa, Urien Rheged, Rhydderch Hen,

Gwallawg and Morgan. Interestingly, in one of the Wessex

royal pedigrees a Frithuwald is made the father of Woden.

One might hypothesize that the Bernician

chieftain was captured by British enemies based at

Dunmeller. As often happened with war captives, he

was selected because of his high political status to be

given us as a triple sacrifice. Probably the

sacrifice was intended to bring good fortune in battle

with the Saxons. By dying a triple death,

Frithuwald became an incarnation of the god Lugh, who

appears to have undergone a seasonal death and rebirth.

Now Frithuwald in OE almost certainly

means either "Peace-ruler" or "Protection-ruler".

But Gyrthmwl Wledic (wledic is cognate with the Germanic

wald) may well have been interpreted by the Welsh as

"Ffridd"-ruler, i.e. "Forest-ruler".

Irish has frith, "a wild, mountainous place, a

forest, a deer forest", Welsh has ffridd, "wood,

wooded land, a mountain pasture, a sheep walk" and

ME has frid, "deer park", from AS fyrhth(e),

"wood, woodland".

Triad 63, which refers to Frithuwald/Gyrthmwl

as a ‘tharv ellyll’ or "bull-spectre",

also has a variant, wherein the phrase ‘charw