Shipwrecks

diving into history

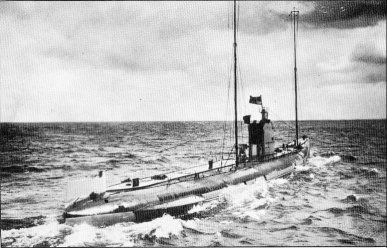

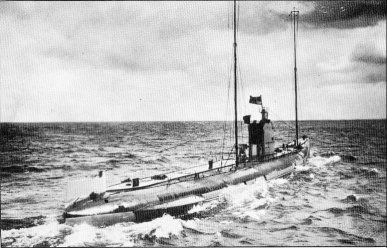

U20

The ship that sank the Lusitania

In 1914 as the world plunged into war, a new weapon - the undersea warship - was entering wide service in the arsenals of several nations. Within the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy) the newly formed Unterseeboot service formed an important part of their combat strength. The second year of war 1915 witnessed one of the most monumental events of the First World War, and a shipping disaster long remembered by all nations. This sinking of the Lusitania had been a perfect demonstration of the new U-boats’ ruthless effectiveness in the hands of a determined commander.

By

the end of 1914 Germany’s Admirals were becoming increasingly aware that their

submarines (only 28 in commission by that stage) were incapable of inflicting

the crippling blockade on British trade envisaged by strategic planners. The

small vessels were unable to adopt the orthodox methods of intercepting enemy

shipping on the surface and taking the vessel as prize. U-boat commanders found

their ships exceedingly vulnerable to counter-attack while surfaced,

particularly after the British First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill

urged merchant ship captains to ram German submarines when they surfaced. The

age of unrestricted submarine warfare was ushered into being, and in February

1915 the German Government declared a policy of attacking and sinking any ships

found within a stated blockade zone, which surrounded Britain and Ireland. They

further declared that while all efforts would be made not to sink neutral

vessels their safety could not be guaranteed within that area. Notices were run

in American papers warning that ships sporting the British flag risked attack

and destruction.

Finally

on 7th May 1915 the almost inevitable result of such a policy

occurred. Cunard cruise ship Lusitania was

torpedoed and sunk just off the Southwestern Irish coast. Of the 2 000 people

aboard, 1 200 were drowned, including 128 neutral Americans. The U-boat

responsible was U20 one

of the “U19” Class of ocean going submarines, built

before the outbreak of the First World War. There were only five vessels

within this group, numbered consecutively U19

to U23. Robust and seaworthy these

undersea hunters were 64.2 metres in length, with a beam of 6.1 metres and

draught of 3.6 metres, displacing 650 tons while surfaced and 837 tons

submerged. Twin diesels pushed the boats at a maximum of 15.4 knots when

surfaced, electric engines for running beneath the waves providing 9.5 knots.

The teeth of these submarines comprised a single 88mm cannon mounted

forward of the conning tower, two bow and two stern torpedo tubes, for which she

was capable of hauling six torpedoes. The 35-man crew lived in the same hellish

conditions that all pioneering submariners enjoyed so much.

The

sinking of the Lusitania still raises

ire and debate amongst people today. While a tragic and unprecedented event, the

label “War Criminal”, used by many, sits uneasily on the shoulders of U20’s commander Kapitänleutnant

Walter Schweiger. The barbarity of “total war” was not new to the world;

civilians had suffered during conflict for centuries, most recently perhaps to

people of the early 1900s in South Africa at the century’s turn. However

weapons had increased in their destructive power, and the remoteness of their

operation. Long range devastation facilitated by technological advances.

Arguments over Schweiger’s criminality continue. The beautiful cruise liner

had been carrying contraband goods through the blockade zone, in the form of

explosives and ammunition bound for the nightmare of the trenches in France.

Although unarmed, she still carried gun mountings from her previous

requisitioning by the British Admiralty, and was officially listed as an Armed

Merchant Cruiser. A single torpedo hit the Lusitania; U20’s last. The great liner took only 18 minutes to go under after

a second explosion contributed to her mortal damage. This second explosion also

has given rise to years of speculation and debate. The two most likely causes

being either a sympathetic detonation of stored ammunition, or highly flammable

coal dust in her storage bunkers ignited by the torpedo explosion. Bodies of

men, women and children continued to wash up on the shores of a stunned Ireland

for weeks.

Schweiger

received the Iron Cross from an unrepentant High Command for his sinking of the

Cruise ship. During the next year he steadily increased his personal score,

affirming his position as one of Germany’s new U-boat Aces. However the days

of U20 were numbered. In October 1916 while running surfaced close to

the shore of Denmark’s Jutland Peninsular the submarine abruptly slammed to a

halt, throwing members of her crew to the steel decking. After frantically

searching for the cause of their grounding Schweiger’s navigation officer

discovered that there was no error with his previously laid course but rather

the compass by which the boat was conned. They had shaved the coastline too

closely and were stuck fast in thick glutinous sand of a shallow bank, within

plain sight from the wide sweeping expanse of Vielby Beach.

Following

a rapid radio call for assistance, nearby German destroyers arrived and

attempted to pull the boat free. However the suction of the wet sand was too

great and after several broken tow chains and growing fear that their exposed

position would soon attract British attention, Schweiger ordered his ship

abandoned and scuttled. Charges were detonated in U20’s

hull and she was left lying

listlessly half exposed near Denmark’s sandy shore, the bottom ripped open.

Schweiger later went on to command the newer U88

adding to his victories until 17th September 1917 when his ship

rubbed against the contact spikes of a British mine, and was destroyed with all

of her crew. After 12 operational patrols Schweiger had sunk 190 000 tons of

enemy shipping, becoming the seventh highest scoring German U-boat commander of

World War One, though probably the most notorious. The wreck of U20 plainly visible and almost intact was dynamited by Danish

authorities during 1925 for reasons unknown, the remains lying for years

forgotten and unrecorded.

During

1984 the skeleton of U20 was found

once more. American author Clive Cussler financed an exploratory search of the

region (documented in his book “The Sea Hunters”) with the help of Danish

archaeologist Gert Normann Anderson. U20

was found to lie in only 17 feet of water, partially buried in the continually

shifting sand. Her conning tower, ripped off in the 1924 demolition attempt,

lies nearby. She was positively identified after divers found an engraved brass

plaque on her propeller shaft coupling, giving the manufacturer’s name and the

date of installation.

The wreck of U20 has not been pillaged by souvenir hunters, like many others to be found so close to shore. In actual fact there are considerably more divers exploring the deep wreck of the Lusitania using mixed gas tri-mix equipment. The German submarine is not regularly frequented by divers and she rests in place corroding over time. Perhaps one day an officially sanctioned artefact retrieval operation could be mounted. If so the pieces should be displayed in a relevant museum. What would these items commemorate? The author is of the opinion that such a display would remember those who died at the hands of U20’s weaponry, aboard the Lusitania and other ships. It would also serve as a memorial to men of the U-boats - indeed all submarines - that gave their lives in two world wars fighting for their countries.