Shipwrecks

diving into history

Marie la

Cordelière

Battle of Brest 1512

by Sarah Burbridge

All was going

rather well onboard the beautiful wooden sailing ships Marie

La Cordelière and Grande Louise.

It was the 10 August 1512 and a party was in full swing.

If the noise of the laughter ringing out across Plougonvelin bay, near

Brest, was anything to go by everyone was having a good time.

Three hundred local dignitaries and their spouses were being entertained

by the rather popular Marie La Cordelière

captain, privateer Hervé de Portzmoguer and the Grande Louise captain Vice Admiral René de Clermont.

The laughter wasn’t to last for long however as suddenly a fleet of

enemy English boats were spotted rounding the headland less than 2 miles

westward. Speed was of all

importance and there was no time to disembark the visiting gentry as the rest of

the fleet were alerted, anchors weighed and the guns made ready.

The English and French were practised foes and both sides engaged in battle

eagerly. Despite the relatively new

technology enjoyed by many of the boats (the Marie

La Cordelière for example was amongst the first boats to sport opening gun

ports aimed to accommodate the recent addition of cannon to fighting ships), the

emphasis of naval combat at that time was still very much on grappling and

boarding to conquer the enemy with hand to hand fighting.

The English fleet outnumbered the French by approximately 3 to 1 and

included the newly built 700 ton flagship Mary Rose, and two ships of 1000 tons, the Sovereign. Mary Rose started the cannon fire

and successfully hit Grande Louise resulting

in 300 dead within the first hour. The

700 ton Marie La Cordelière picked

on a smaller rival, the 400 ton Mary

James whose captain, Anthony Ughtred, did well at holding his own until help

from Sovereign arrived, followed by

the Regent.

With almost an hundred ships in the cramped channel, skilful captains

were required on both sides to work their men playing the wind and the tide in

order to gain windage and therefore advantage over their adversaries. As the

battle progressed the English appeared to have the upper hand until the much

esteemed Hervé de Portzmoguer concentrated his assault on the powerful enemy ship, the Regent,

eventually grappling her and boarding her.

The remaining vessels continued to fight in confusion, several being sunk

by cannon fire, some striking nearby rocks, and others retiring in disarray.

With the Regent and the Marie La Cordelière physically tied together

bitter hand to hand combat ensued. Arrow

and crossbow bolts were aimed but fighting conditions were made even harder as

the two ships rolled in the swell, their sides often crunching together

splintering wooden beams. Above

their heads flagging sails cracked louder than the sound of nearby cannon fire

as the wind caught them. Despite

Regent’s main mast being broken by a cannon ball and her wooden hull beginning

to burn as flaming projectiles were thrown by Marie La Cordelière’s crew, she

appeared to be the stronger of the two vessels. The fighting continued for more

than two hours and the decks became red as a mixture of blood and wine washed

over the once party boat. Hervé de Portzmoguer decided he had one last chance

to destroy the English vessel and he set his own powder magazine on fire thus

turning Marie La Cordelière into a

floating bomb. Within seconds there

was a violent explosion that instantly sank both ships.

Remaining vessels of both nationalities were shocked and stopped fighting

immediately in order to rescue any survivors.

Unfortunately not many survived this terrible spectacle - the English

commander, Thomas Knivet was killed by the explosion and Hervé de Portzmoguer was

thrown into the sea where he was drowned, dragged under by the weight of

his own armour. It is estimated that between 1000 and 2000 people lost their

lives with just 20 men rescued from the Marie La Cordelière and 180 from the

Regent.

It has never

been firmly established how many ships were sunk that day - BMRS continues to

search.... The battle itself

produced no clear victor, with the French and English fleets continuing their

sporadic engagements for years to come.

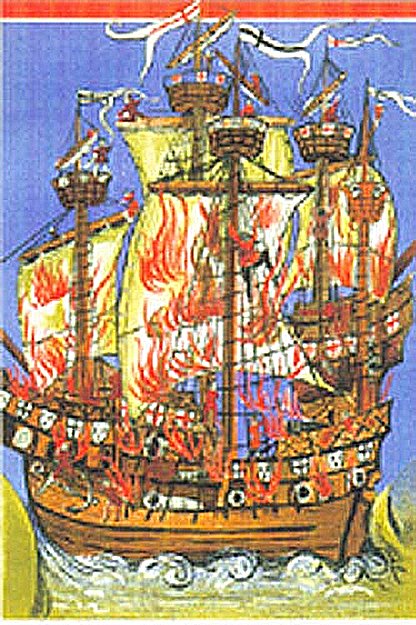

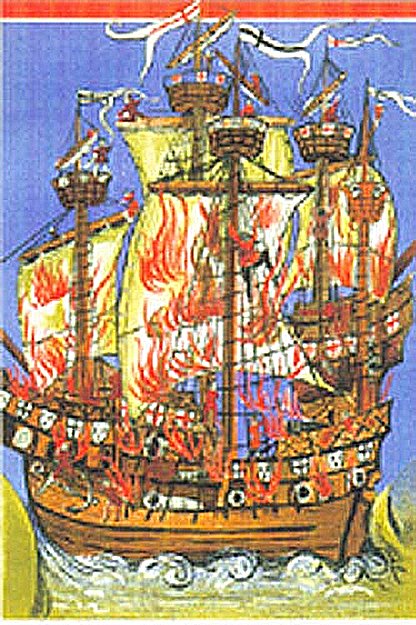

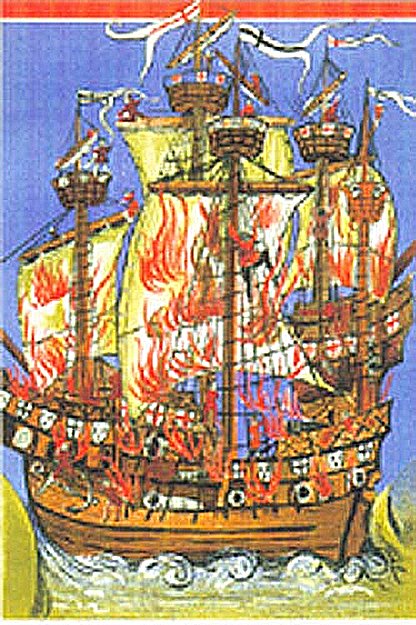

An artist’s impression of a typical16th

century galleon, in this case English. La

Cordelière probably closely resembled this design