May 31, 2005

The

Prodigal

Son

(Opera Pia Jona Ottolenghi - Aqui Terme - Al.)

Roberto Salvini, a

Master of art criticism, speaking of the sculpture by Martini, writes:

The

movement of

the two figures one towards the other, which is represented at the very moment of

its

arrest, the inter – twining of the arms into the beginning of an

embrace, the

sharp and questioning glance of the

father, they are all elements which make the reading of the issue

involved

plane and clear. At the same time, the Roman – style clothes hint at

the

historical timing of the evangelist parable.

However, nothing of all this would be relevant to the value of

the oeuvre

d’art, if it had not been expressed through an individual language,

the

central theme of which is the permeating of the air and the light of

the

plastic surface, the porousness of the material, which seems consumed

by time. In

this way, a dimension of space is created around and inside the

group of

the two images, which are projected into a mythical distance (Guida

all’arte moderna, Garzanti, Milano 1954, p.83 [the translation from

Italian

is mine])

It seems to me,

that nothing can be added to a so brilliant critical assessment.

However… the

sensation is that there is something more in the representation, a

story inside

the story, which does not invalidate the manifest representation, but

that hints

at a more archaic and latent substance: a deeper layer from which the

present

image was engendered.

When I first looked

at the sculpture, I was at a certain distance, and I had not yet read

the title

of the composition.

The primal

sensation, which is always the one that better reconnects to our

unconscious,

was that we are dealing with a scene describing a wrestling. It was as

if the

two men were to hold each other in a Greek – Roman wrestling position,

or they

were two Judo – wrestlers at the beginning of their fight.

Then, coming

closer, I realized that the scene was dealing with an embrace. It was

as if,

under the artist’s fingers, an act of mutual aggression had been

transformed

into a loving thrust.

Only at this point,

I reminded what I had previously written in Rembrandt and the Prodigal Son: under the

Gospels’ overlay, were hidden the mnemonic traces of the youngest son

of the

Primal Horde, who was the vicar of his brothers, and who returned

home in

order to kill the Father. This repressed content was captured at

first by

my unconscious, as it occurs to other visitors.

If we analyze

Salvini’s comment, we find the same traces of the primal event, which

had been

unconsciously captured by the great critic: “ The

movement of the two figures towards each other represented at the very

moment

of its arrest, the inter – twining of the arms into the beginning of an

embrace

[the wrestling], the sharp and questioning glance of the father [as

in the mutual gauging of two wrestlers] they are

all elements which make the reading of the issue involved plane and

clear [at

which level, the manifest of the latent one?]… which seems consumed

by time. In

this way, a dimension of space is created around and inside the group

of the

two images, which are projected into a mythical distance" [= into an archaic

time, which is timeless as prehistoric and psychic events].

Art is one of the

most important instruments for decoding unconscious collective

contents. Those

are transmitted from the artist to the public at the unconscious level,

circumventing

the censoring filter of consciousness. The spectator captures them and

identifies with.

Dealing

with art

Freud wrote: “art offers

substitutive satisfactions

for the oldest and still most deeply felt cultural renunciations, and

for that

reason it serves as nothing else does to reconcile a man to the

sacrifices he

has made on behalf of civilization ("The Future of an

Illusion" (1927), in The Standard Edition of the Complete

Psychological

Works of Sigmund Freud, The Hogarth Press, London 1953, Vol. 21,

p.14).

In the

biblical parable, the central motive of the youngest son

who returns home in order to kill the Father was repressed. The scene

of

reconciliation was overlaid on the act of aggression, according to the

common

proposal of religions. However, the aggressive element, having been

repressed,

pressed for recognition too.

Every

repressed content, which is inhibited from discharging its energies,

accumulates in our psyche, and causes a certain amount of sufferance.

Jacob was left alone, and wrestled with a man there

Theodor Reik, in his essay “The Wrestling of Jacob” (in Dogma and Compulsion,

International Universities Press, New York 1941, pp. 229 – 251),

interprets the biblical story of the wrestling of Jacob as the mnemonic

trace of a puberty rite. In those occasions, the adults of the tribe,

who represent a paternal image and in the biblical myth are represented

by the angel, threaten the youngsters and eventually circumcise them as

a substitute of castration. Reik writes:

As Freud says, civilization demanded instinct renunciation, namely

renunciation

to the aggressive drive towards the

Father, and permitted only the expression of the loving side of the two

– faced

medal of the ambivalent relation between Father and Sons. The result is

the

repression – accumulation of the other side. The artist, introducing in

his Oeuvre

the repressed element, helps the discharge of accumulated energies and

the

subsequent relief.

Marc Chagall and The Wrestling of Jacob (Dec. 5, 2005)

until the breaking of the day...

...The man said, "Let me go, for the day breaks."

Jacob said, "I won't let you go, unless you bless me."

He said to him, "What is your name?" He said, "Jacob."

He said, "Your name will no longer be called 'Jacob,'

but, 'Israel,' for you have fought with God and with men,

and have prevailed." (Gen. 32:24-8)

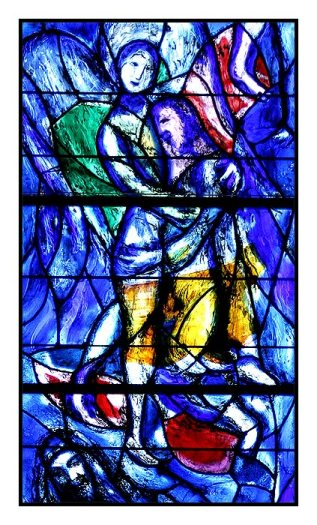

Chagall’s vitrage in the Fraumunster (Zurich)

Arturo Martini consciously (at the manifest level) expressed the loving

pole of the emotional ambivalence in the father – son relationship, and

unconsciously (at the latent level) released the aggressive element.

The title of his sculpture speaks of love and reconciliation, while, at

the same time, the embrace of love condenses also the aggressive

component of a struggle.

Marc Chagall did the opposite. The title of this scene is “The

Wrestling of Jacob with the Angel”, hinting at an aggressive encounter

between Jacob and the angel, messenger of God and his will doer. Jacob

wrestled with God Himself, as is written: "you have fought with God and with men,

and have prevailed".

God is always a paternal image. The manifest scene speaks of a

struggle between father and son. This time the repressed element is the

loving pole of the emotional ambivalence.

However, the latent unconscious element is pressing for recognition, too.

Staring

at this sublime work of art, we are permeated by a compelling sensation

that we are dealing not with a struggle but with a moving encounter of

love and reconciliation.

we find a reference to the

tradition that Hercules had to engage in such a wrestling contest on

two occasions; once with Hippocroon, when the hero, curiously enough,

suffered an injury to the hip, and once in the Palaestra of Olympia,

when he encountered his father Zeus, who for some time wrestled with

him as an unknown adversary, but finally revealed his identity. Another

observation may perhaps appear more significant: the rabbies declare

that the vein which the God of Jacob injured is identical with the

phallus. The same opinion is maintained in the book of Sohar (Parascha

Wajischlach, p. 170). We venture to suggest that psychoanalysis has

recognized this and other displacements in the myths in question, and

that the symptom of limping has been interpreted as a euphemistic

reference to castration. Now we seem to see the whole episode in a new

light: The god castrates Jacob, or at least attempts to do so. (p.238)…

Therefore, what began as an hostile encounter between Father and Son,

like in the wrestling of Jacob, ends in an embrace of reconciliation,

like in the parable of the prodigal son.

Reik concludes:

… The paternal generation, which after initiation accepts the sons as

equally privileged, now consents to their desires. In the course of

evolution this consent, conditioned by the emotional trend of the

ambivalent attitude, assumes an increasingly prominent position in the

foreground, until the original meaning of the initiation ritual is no

longer perceptible. With the progressive repression of hostile impulses

the paternal affection and care for the young become the central point

of the initiation. (p.240)…

we should regard the words "I will not let thee

go except thou bless me" as the expression of the eternal truth that no

man can enjoy undisturbed happiness in life and love who is still

fighting with the shade of his father. The partial conquest of the

father is, like the reconciliation with him and his

memory, a condition of cultural progress. (p.251)

George Minne: The Prodigal Son

Links:

Rembrandt and the Prodigal Son. On Elder and Youngest Brothers

Pinocchio. The Puberty Rite of a Puppet