|

CLIVE SINCLAIR: One name is stamped indelibly on most British computers — Sinclair. |

|

|

CLIVE SINCLAIR epitomises all that is best in British industry — or at least people in high places think so. When Margaret Thatcher presented the Japanese Prime Minister with the latest Sinclair machine in front of a television audience of hundreds of millions, many must have been delighted at this demonstration of Britain outdoing the Japanese in high-technology consumer goods. |

Others who, after four months, were still waiting for their Spectrums to be delivered or whose machines had proved unreliable on arrival may have viewed the spectacle with less enthusiasm. But love him or loathe him, no-one can deny Sinclair's pre-eminence in silicon Britain or his startling record of technological innovation. In the early 1970s he produced the world's first pocket calculator and followed it up with the Black Watch — the first to have all its electronics on one chip. |

He opened this decade with the ZX-80, the first mass-produced home computer and soon followed it up with the ZX-81 and Spectrum, selling 500,000 computers in three years. Now Clive Sinclair has become as synonymous with computers as Hoover is with vacuum cleaners. Yet unfortunately Sinclair's ventures have not always been as successful as expected. His calculator was soon overwhelmed by competition form the Far East and his digital watch had to be withdrawn because of unreliability and delivery delays, leaving the field clear for the Japanese. |

Partly in response to these tribulations he has developed an unusual way of working. Despite a turnover of £30 million a year and rising, he employs just 50 people who concentrate on research, development and marketing while he farms out production of his proven inventions: "We're a nexus; we cause things to happen then stand back." With customers grumbling about delivery delays and a Japanese computer invasion on the cards can Clive Sinclair stop history repeating itself? 'We make more computers than Japan' |

"That's a long time ago in a different business. Several Japanese companies have launched personal computers and then pulled them out. Time and again they have failed; they are out because they can't get in. We make more computers than the whole of Japan. As long as our volume is at least as high as theirs — and it is a great deal higher — I don't see how they can compete. They can't do it at a low price". If the Japanese cannot do it, how about Binatone's computer with 16K colour and sound for £50 to be launched in January? — "I'll believe it when I see it. Binatone wouldn't know how to design the thing and we don't know of anyone in the Far East who could do it for them." |

Sinclair's £125 Spectrum has become the standard by which other micros are judged: — "We started with the ZX-81, where people wanted something extra — a moving key keyboard, colour and sound and a large internal memory. The Spectrum was a solution to that." While the 16K of RAM and quality of colour were an instant success, the keyboard was criticised for its lack of a full-size space bar and for what one rival called the "dead-flesh" feel of the keys. |

|

"People who've actually used the keyboard find it very attractive. It's not the same as other people's. It's our own design, low cost to produce but very satisfactory." But even Sinclair has to concede that it does not make word processing easy: "The keyboard may be a limitation but you could put another keyboard on it if you were really that desperate." The success of the Spectrum has brought its own problems. Hundreds of Sinclair customers have written to or telephoned Your Computer to complain about delivery delays. "They're entitled to complain and we don't take it lightly. We did get things wrong but we've moved heaven and earth to correct it — the criticisms are justified and we'll make damn sure it doesn't happen again." |

What angered customers most was Sinclair's failure to give realistic delivery dates and the lack of information about problems with the Spectrum's printed circuit board and power pack which have since been solved. 'They're entitled to complain and we don't take it lightly' Sinclair prefers to interpret the delays as a back-handed compliment to the Spectrum. "Yet again, we've been amazed by the demand. It's not that we don't learn, it's just that this time we deliberately didn't advertise in the national press to start with in order to restrain demand. |

"Nonetheless sales of the Spectrum have been just as high as with the ZX-81 which we advertised nationally despite the fact that it is more expensive. In addition we've been behind schedule but we're on schedule now and catching up rapidly." Clive has little time to read micro magazines: "There are so many that I only have time to glance at them" but he had read September's Your Computer interview with Hermann Hauser of Acorn with more than passing interest. |

|

Ever since the BBC chose Acorn rather than Sinclair to produce the BBC Micro, the Cambridge air has been suitably blue with allegations and counter-allegations between the rival firms. Sinclair is particularly scathing about Hauser's claims for the Electron, Acorn's Spectrum challenger due to be launched next month: "The Electron isn't here for a start — not expected by them until the end of the year — and not by anybody wise until next year. It will come out a year later than the Spectrum and will be way behind it in technology. |

"It will have — as Hauser says — more RAM, more ROM, more ULA, for the simple reason that in my view they don't know how to produce a machine half as well as we do. Ours isn't complex if you mean it has fewer chips — but that of course is the clever bit about it. It takes them 32K of ROM to do the interpreter and so on, which we do in 16K: they need 32K RAM minimum because their display takes 20K to do exactly the same as our display does in 8K. It's going to be much more expensive to make than the Spectrum and it only does the same job — in some ways not as well. |

"They were announcing it at the same time as we were announcing the Spectrum — by the time it does appear I'm afraid the competition will be so fierce in that sector of the market that I think it will be too late. Hauser says that if he does have a problem, he just picks up the telephone. Well, we don't — we do it all in-house." |

|

Sinclair is no less damning about the BBC machine. "If it wasn't for the fact that the BBC for their strange reasons allow Acorn to stick a BBC logo on their machines I don't think they would sell many computers. Hauser says it's an Apple and Pet competitor. Those machines were designed a long time ago and the Spectrum far exceeds their specification — and so it should, it's up to date." |

Hauser's claim that BBC Basic is becoming the standard particularly offends Sinclair's sensibilities: "Sinclair Basic is the most widely used in the world today — by the end of this year half the computers produced in the world will have our Basic on them — if that's not a standard what the hell is?" Sinclair freely admits that his Basic may not be suitable for all applications but rather than restructuring his Basic he believes in "Horses for courses. We offer a whole range of languages for the Spectrum." |

Sinclair damns his other competitors with faint praise. "Commodore is a very effective company but technically way behind. The again, Commodore makes many machines we don't have anything to compete with." He does not see Commodore's forthcoming Max as a threat either: "It's a games machine, that's all." As for the Dragon and purpose-built Spectrum-bashers like the Oric he will only say "Wait and see". |

|

Next month Clive Sinclair takes the wraps off his most closely guarded secret, the Microdrive. If it is half as good a storage system as he claims, his competitors have much to fear. Until now if you wanted to use your machine to handle information you could either store the data on cassette and wait for hours when you needed it, while the computer found the right pieces of tape, or spend a small fortune on a 5.25 in. disc-drive system and do the job properly. Now the manufacturers are miniaturising the drives to take 3in. and 3.5in. discs and bringing prices down as well. Sony, Hitachi and BATS have all produced small drives which could be on sale for less than £200 by early next year, but once again Sinclair upstaged his rivals by announcing — last St George's Day — that he would release a 100K rapid-access storage system, the Microdrive, for £50. |

|

|

Sinclair's reluctance to release any further details since April, together with the low price, has fuelled speculation that his micro-floppy might not be a real disc drive. Sinclair will only say "it will do exactly the same job as the other drives" and he is particularly indignant at Hermann Hauser's claim that the Microdrive will be obsolete before its launch. "The micro-floppy is the most important thing we're doing and contrary to what Hermann Hauser supposes it is actually well in advance of the 3in. and 3.5in. machines that the Japanese are doing and less expensive." |

As for access times: "They're all a sight faster than any customer is ever going to need, it'll do anything you want it to do. "The Japanese ones even for large volumes will retail at twice our price. I was talking with Adam Osborne about this and he wants to buy ours even though he can buy anywhere in the world". Like Sinclair, Osborne was once an electronics writer before he started building the briefcase computers which now carry his name and which Sinclair admires. "That portability thing makes it very sexy but the true virtue of his machine is that it's all in one package. You don't have all those cords trailing about to plug together." |

It comes as no surprise that Osborne is working on a less cumbersome successor to his present machine incorporating Microdrives. Could Sinclair be working on a lightweight briefcase machine himself? He has spent 10 years perfecting the flat-screen television and now has the Microdrive. Both are likely to find a place in next year's new Sinclair, which will not be called the ZX-83. |

|

"That's a likely product. We have the flat-screen technology, we have the Microdrive technology. Late next year we'll have a machine which is not a replacement for anything we have now, and which will have the display and the drives. It is for that reason that I don't think our opposition stands a heck of a chance — because we can do that and nobody else can. Obviously it is going to cost a lot more than the Spectrum. |

Next year's model should also step straight into the era of electronic mail. It will incorporate Sinclair's telephone Modem which will become available as a Spectrum add-on early next year for about £50. "When you're linked to the telephone you can send a message from one computer to another, so you've got electronic mail." |

The modem will also allow Sinclair owners to access databases like Prestel and viewdata. Sinclair plans to use Prestel to sell programs. Sinclair owners will be able to download programs from the telephone line. "It's a good way to sell software, the sort of thing we're doing will probably be a great boost for Prestel. |

|

Sinclair seems confident that Prestel will at last make the long-predicted breakthrough, if only because he expects hundreds of thousands to buy Spectrums and Modems. " We won't get our finger burnt because we're simply offering a facility." Sinclair believes that the size of this market may encourage others to set up their own databases: "Other companies will set them up — we're talking to them about it now." Electronic mail may also extend the useful life of the ZX Printer, "From time to time you need hard copy either for electronic mail or for the data you're taking from the Post Office viewdata system. That's where our printer becomes so important." |

He rejects criticism that the print-out on narrow aluminised paper is unsatisfactory: "We're not replacing it at all because that printer has the unique ability to do graphics very rapidly, to print out a complete screen of data in 12 seconds. No other machine can do that at anything like the price." Those who want typewriter quality print-outs will have to wait another year for a solution from Sinclair but, in the meantime, next month's release of the Sinclair RS-232 interface will make it easier to find a compatible printer. |

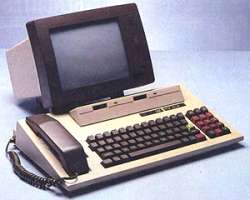

"We are developing a plain-paper printer — not before the end of next year — but that's a full-size printer for letters, stationery, invoices, and things like that." Sinclair is also working on a desk-top executive machine for ICL which will incorporate many of the same ideas. "A couple of Microdrives, 7in. or 9in. flat screen, an enhanced version of our Basic, and a telephone which links in." Inside the ICL will be an expanded Spectrum and the machines could be networked together or communicate over the telephone. |

|

"It will replace the paper that moves around at the moment. An executive can send data to anyone else in the net, receive messages on it, and his mail will come through there. It will be arranged so that somebody who doesn't know anything about computers can use it — just get a menu up on screen and select. The price will be pretty modest because we have the best technology — otherwise ICL wouldn't be coming to use." 'That's what a telephone is going to look like' Tony Baden of Bug-Byte believes that every home will have a home computer by the end of next year — Sinclair is slightly more cautious: "We can't make them that fast, but there will be millions, because" he points to an artist's impression of the ICL machine "that's what a telephone is going to look like one of these days. Very few will sit down to program them but people will need facilities, like electronic mail, that it offers." |

|

|

Among other facilities Sinclair expects to offer by 1984 are expert systems giving individual tuition to children and medical advice to the family. Could the Spectrum be adapted to do this? "Perhaps the Spectrum — certainly son of Spectrum. I think the home doctor is the application we'll tackle first — that's the vital one. We'll get to the point where we have expert systems linked into teaching, offering infinite patience and infinite attention." Cynics might suspect that a government might use this as an excuse to do away with the health and education services but Sinclair prefers to believe that: "It will enable us to make better use of a service resource." |

Sinclair is optimistic about our electronic future although he acknowledges that millions more will be thrown out of work by the new technology. "Computers are not going to suddenly and radically change our lives — they'll gradually improve them. The only way in which there can be new jobs is by hundreds of thousands of people starting new businesses — in the service industries, in new technology and in the life sciences." |

Sinclair believes that the writing is on the wall for the big corporations. Small businesses "will replace the megalithic companies — the vast employers of people." Ironically his own computers are made by Timex, an American-owned multinational. He believes that the information revolution could lead us into a new Golden Age of civilisation, rivalling Augustinian Rome, Louis XIV's France or Elizabethan England. Hopefully life for the majority of people would not be as miserable in Clive's Golden Age as it was in the societies he admires. |

|

Renaissance prince he may be, but Sinclair resisted the temptation to be photographed next to an imitation Greek statue on the balcony of his Chelsea service flat. "No, it's a horrible thing". In such spare time as he has Sinclair is chairman of British Mensa, an organisation for people with high IQs. He laughs at the idea that there is anything sinister about the head of the world's largest home-computer firm also being head of Mensa. |

Contrary to popular belief Clive Sinclair does not have square eyes with little white squares in the bottom left-hand corners. He is a keen runner: "I run seven or eight miles every morning, clear my head, get rid of my hangover, and straighten out the day." |

So does he fear for the fitness of all those people pumping programs into their Sinclairs through the night? Could he find himself facing a million lawsuits from ZX owners claiming his computers have turned them into social hermits who can only communicate in machine code? "No", Sinclair smiles, "We program them so that if they make a claim, the machine explodes and blows them to bits." You have been warned.¨ |

The collaboration with ICL did eventually lead to the

The collaboration with ICL did eventually lead to the