TITLE: Graham Parker's Up Escalator is a downer

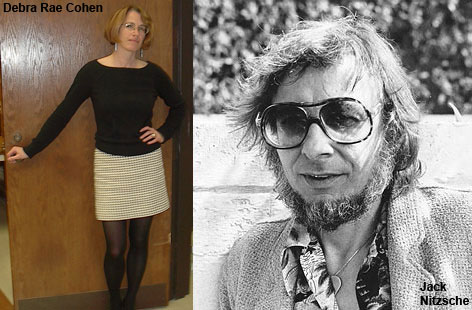

AUTHOR: Debra Rae Cohen

SOURCE: Rolling Stone

DATE: 24 July 1980

There's a big gap between being a rock & roll classicist and actually turning out classics. Specifically, it's the difference between reaffirming traditional rock truisms and reinvigorating them--between, say, Tom Petty, whose rich and ringing minianthems meld half-a-dozen heartfelt homages, and Graham Parker, who aims higher without thinking about it.

Parker's early records--like The Band's--didn't sound like anybody so much as everybody. This music tapped into the mysteries of rock & roll at their source and washed back all the accumulated resonances of the years in between. Graham Parker's voice was like a King Curtis sax line, urgent and visceral, powered by passion instead of technique. Emblematic moral concerns--like the struggle for honorable survival in a rigged-deck world--gave Parker's songs a consistency of vision as surely as Bruce Springsteen's trademark landscapes did his. Parker's was a passion informed by the awareness of restraints, and on last year's Squeezing Out Sparks, he fashioned (along with producer Jack Nitzsche) a sound to match: taut as isometrics, with succinct hook-filled guitars and lots of empty space. The Rumour seized Parker's passion and focused it, honed it like a knife.

Regrettably, on The Up Escalator, producer Jimmy Iovine (and perhaps, though I hope not, Parker himself) has taken the lessons of the last LP and torn them down for high-rises. The new album seems like an attempt to "gentrify" Parker, to turn him into a commercial classic-by-association by surrounding him with blue-chip artifacts: e.g., the Chase Manhattan mural cover art, a host of "legitimizing" guest musicians (including, O Lord, the Boss himself). Such an attempt merely devalues Graham Parker's artistry as well as his past achievements. It also drastically undermines his material.

Throughout the record, Brinsley Schwarz's and Martin Belmont's guitars are submerged in the mix, while all the free space is stuffed with the sterile keyboard flourishes of Nicky Hopkins, who replaces the departed--and impeccable--Bob Andrews. Hopkins' brittle honky-tonking has been a cliche for years, and his innocuous playing is completely inappropriate to Parker's music. (He transforms Devil's Sidewalk into something about as threatening as Park Avenue.) There isn't a cut--except the deliberately rinky-dink Stupefaction--that Hopkins doesn't deaden with his all-purpose stylized noodling. The result is a sound that's turgid and passionless: Graham Parker sanitized. It makes the opening number, No Holding Back, seem as tauntingly ironic as last year's Don't Get Excited. But the catch is that No Holding Back isn't meant to be ironic.

In addition to sabotaging songs, The Up Escalator's lackluster sound brutally exposes failures of performance, composition, and nerve. This LP has an odd slapdash feel. It's as if, in belatedly attempting to reconstruct (rather than capture) Parker's rough attack, Jimmy Iovine mistook sloppiness for soul and recorded an album of reference vocals. On Squeezing Out Sparks, Parker's voice trampolined off his tight instrumental backing, gaining power and momentum with each controlled collision. Here, instead of swapping tensions, he's forced to create his own, plugging the gap with technique. But the last thing that Graham Parker should do is learn how to sing. There's an unwelcome tentativeness to some of his vocals now. Lines drift off uneasily, as though he's not sure where to put them. When Parker slows and drops his voice before the chorus of the poignant The Beating of Another Heart, it sinks beneath the plodding drumbeats as if it's caught in quicksand.

Paradoxically, in Endless Night (the much-heralded "duet" with Bruce Springsteen that opens side two), sloppiness actually works to advantage. Springsteen enters the track--basically an uninteresting throwaway--in the middle of the second verse as though he'd suddenly wandered into the studio. But that demystifying haphazardness--and the just-singing-along irrelevance of Springsteen's harmonies--give the song a heady vulgarity and spontaneous exuberance that the rest of the record totally lacks.

Amid the mediocre, incomplete, and ill-served tunes, however, are a few numbers that--potentially--could stand with Parker's best work. With its stinging guitar accents and edgy, obsessively repeated hook, Empty Lives seems constructed for franticness, speed, and tension. The dramatic extended fade-and-return is just the sort of thing that The Rumour would flex their muscles around masterfully in concert. Even here, they very nearly manage it, until the abrupt addition of Jimmy Maelen's intrusive--and, it sounds to me, carelessly off-the-beat--percussion trips up the pace like a dog yapping alongside a racing cyclist.

Despite its flaws, though, Empty Lives is the LP's most successful song, as well as the most thematically engrossing. Like much of The Up Escalator, it's concerned with the pull of obsessions. Parker parades obsessions through his lyrics: temptations and hungers, desires fulfilled and terribly mismatched--from the cheap-shot excesses that squelch insight and sensuality in Stupefaction to the lust for integrity that frustrates fervor in The Beating of Another Heart. People stare into the sun until they go blind, mistake gluttony for satisfaction, play Procrustes until others fit the measure of their keening wants. Graham Parker, as usual outraged but not immune, shoulders his way through with the self-aggrandizing paranoia of the crusading moralist. In Empty Lives, desire is only a mask for the kind of hollow soul-stealing that's as infectious as a vampire's bite. Contact doesn't enrich but leaves you reeling with the shock of loss. Moans Parker, trapped unaware into craving: "Bring me some water. Bring me cocaine. Bring me something lethal. Something that leaves no stain. But please don't make me feel that emptiness again."

Even the most honorable emotions are vulnerable and therefore suspect. "I make a feeding frenzy out of loving you", Parker bellows in Jolie Jolie, a song to his recent bride. It's the album's most arresting line. Like the swiftly flickering passions of The Pretenders' Up the Neck, love--when held a beat too long--turns into sheer appetite. Almost offhandedly, Parker introduces surreal, horrific images ("In the Mexican quarter now/The women so hungry that they eat their own kids"), juxtaposing them with his lover's exhortations to cast a cautionary shadow over his own happiness even while the tune's jaunty chorus celebrates it.

That these compositions can come across so potently despite the sonic sabotage of their arrangements simply reconfirms Parker's stature as a writer and performer--and, by extension, the stunning mediocrity of this record as a whole. The Up Escalator is a waste of some terrific material. More important, it's a waste of Graham Parker's time. He should know that blue chips are a lousy investment in an inflationary era. These days, all the smart money is going into art.