|

GRAHAM SUTHERLAND

1903-1980

|

|

GRAHAM VIVIAN SUTHERLAND was born on August 24, 1903 in London, the son of a lawyer who later became a civil servant. He was primarily a painter of imaginative landscapes, portraits and still lifes. From 1920 to 1925 he studied at Goldsmiths' College School of Art, specializing in printmaking. In 1926 Sutherland converted to Roman Catholicism. The following year he married Kathleen Barry. He taught at Kingston School of Art, Chelsea School of Art, Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford, and at Goldsmiths', until after World War II when he decided to become a full-time painter. GRAHAM VIVIAN SUTHERLAND was born on August 24, 1903 in London, the son of a lawyer who later became a civil servant. He was primarily a painter of imaginative landscapes, portraits and still lifes. From 1920 to 1925 he studied at Goldsmiths' College School of Art, specializing in printmaking. In 1926 Sutherland converted to Roman Catholicism. The following year he married Kathleen Barry. He taught at Kingston School of Art, Chelsea School of Art, Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford, and at Goldsmiths', until after World War II when he decided to become a full-time painter.

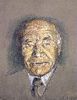

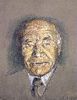

Image above: "Self Portrait," 1977, © oil on canvas National Portrait Gallery

In 1940 Kenneth Clark invited Sutherland to take part in the War Artists' Scheme. From1940 to 1945 he worked as an official war artist, drawing scenes of devastation, blast furnaces, tin mining and quarrying. It was during this period (1945-46) that Francis Bacon formed a friendship with Kathleen and Graham Sutherland. Sutherland was one of the first to champion Bacon's work. According to Bacon, it was Graham who "became interested in what I was doing and spoke about me to Erika Brausen, who had the Hanover Gallery."

During the mid-to-late forties, Sutherland and Bacon often showed their paintings alongside each other. Sutherland seems to have been influenced by Bacon in the early 1950s, "though the traffic in ideas was not wholly one-way. . . in some cases Graham seemed to be painting Bacon-like works on a give theme before Bacon himself tackled it."

MORE FRANCIS BACON HERE

In 1941 Sutherland had his first retrospective (with Henry Moore and John Piper) at Temple Newsam, Leeds. In 1946 he had his frist one-man exhibition in New York at the Buchholz Gallery. That same year he painted the "Crucifixion" for St. Matthew's Church, Northamption. During this same period Bacon was working, in the South of France, on his "Studies for a Portrait after Velezques' Pope Innocent X."

After the predominantly Wales-inspired first period of 1934-36, and the war years of 1940-46, Sutherland enjoyed a third period, from 1947 through the mid-1960s in the South of France where he painted a number of new motifs, including palm palisades, vine pergolas, etc. In 1952 Sutherland was commissioned to design a large tapestry for the new Coventry Cathedral. That same year his work was exhibited in the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The Sutherlands bought La Villa Blanche at Menton, South of France in 1955.

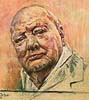

During this period Sutherland painted his first portrait commission, of Somerset Maugham, which proved to be such a success that he received numourous commissions, usally from the rich and famous. However, in the case of Winston Churchill, the portrait was so disliked that it was destroyed on the order of Winston's wife in 1955 or 56. On November 30, 1954, at the presentation ceremony of the portrait in Westminster, Churchill, who loathed the painting, remarked with wryness: "The portrait is a remarkable example of modern art. It certainly combines force and candour . . ."

The National Portrait Gallery in London organized a retrospective of Sutherland's portraits in 1977. He died in London on February 17, 1980. The Tate Gallery gave him a major retrospective in 1982.

|

|

SUTHERLAND PORTRAITS

|

SLIDE EXHIBIT

|

|

Images in Slide Show:

- Portrait of W. Somerset Maugham I, 1949

oil on canvas 54 x 25 inches

© The Tate Gallery, London

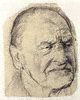

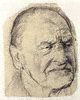

- Study of Lord Beaverbrook, 1950,

oil on canvas

© Beaverbrook Art Gallery, NB, Canada

- Portrait of Edward Sackville-West 1954

oil on canvas, 66.75 x 30.5 inches

private collection

Edward Sackville-West was a distinguished writer and musicologist, and a close friend of Graham Sutherland. He was hypersensitive and highly strung and seemed "to stand permanently on the threshold of death's door." Kenneth Clark Sutherland deliberately tried to create 'an impalpable atmosphere'. The sitter is perched on a high stool. . . his hands nervously clasped, and his expression tense, almost anguised.

- detail: Edward Sackville-West

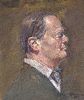

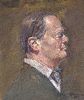

- Study of Winston Churchill's Head Facing Slightly to Left, 1954

oil on canvas

- Study of Churchill's Head facing Half Left 1954

oil on canvas, 24 x 20 inches

- Study of Churchill on Toned Canvas, 1954

oil canvas, 17 x 12 inches (432 mm x 305 mm)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

- Three Drawing Studies of Churchill, 1954

© National Portrait Gallery, London

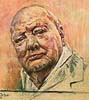

- Portrait of Sir Winston Spencer Churchill, 1954

oil on canvas, 58 x 48 inches

Painting destroyed by Mrs. Winston Churchill

( articles on this painting )

- detail: Portrait of Sir Winston Spencer Churchill

- Portrait of Max Egon, Prince von Furstenberg, 1959

oil on canvas 65 x 55 inches

© Collection of Joachim, Furst zu Furstenberg

- Lord Goodman, 1973-4

oil on canvas, 37.75 x 37.75 inches (959 x 959 mm)

Presented anonymously through the Friends of the Tate Gallery ©

- Self Portrait, 1977

oil on canvas, 20.75 x 19.75 inches (527 mm x 502 mm)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

|

|

|

The controversial portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, which Churchill himself hated because he said it 'makes me look half-witted' and which was destroyed (on the order of Mrs. Churchill) out of anger only a year or two after its completion, was commissioned in 1954 by past and present members of the House of Lords and House of Commons, and presented to the great statesman as a celebration of his eightieth birthday at a ceremony in Westminster Hall on November 30, 1954. Although Churchill would have preferred to have been painted in his robes as Knight of the Garter, the All-Party Committee has specified that he should be represented as the House of Commons had always known him, and the spotted bow-tie, black coat and waistcoat and striped trousers in which Sutherland painted him were indeed the dress familiar to every one of Churchill's parliamentary colleagues. At the first sitting Churchill asked Sutherland: 'How will you paint me, as a cherub or the bull dog?' 'He showed me a bulldog so I painted a bulldog.' Though the picture could never have been other than a portrait of an old man. . . Sutherland conveyed to the full the distinction and tenacity of the elder statesman. . . The pose is firm, the weight of the form massive, and Churchill's legs seem like mighty columns precisely because they have been truncated. 'The tyranny of the edge of the canvas, where to end the movement, is always a great problem with any kind of painting. . . Where to make the cut between the knee and the foot is not easy.' The controversial portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, which Churchill himself hated because he said it 'makes me look half-witted' and which was destroyed (on the order of Mrs. Churchill) out of anger only a year or two after its completion, was commissioned in 1954 by past and present members of the House of Lords and House of Commons, and presented to the great statesman as a celebration of his eightieth birthday at a ceremony in Westminster Hall on November 30, 1954. Although Churchill would have preferred to have been painted in his robes as Knight of the Garter, the All-Party Committee has specified that he should be represented as the House of Commons had always known him, and the spotted bow-tie, black coat and waistcoat and striped trousers in which Sutherland painted him were indeed the dress familiar to every one of Churchill's parliamentary colleagues. At the first sitting Churchill asked Sutherland: 'How will you paint me, as a cherub or the bull dog?' 'He showed me a bulldog so I painted a bulldog.' Though the picture could never have been other than a portrait of an old man. . . Sutherland conveyed to the full the distinction and tenacity of the elder statesman. . . The pose is firm, the weight of the form massive, and Churchill's legs seem like mighty columns precisely because they have been truncated. 'The tyranny of the edge of the canvas, where to end the movement, is always a great problem with any kind of painting. . . Where to make the cut between the knee and the foot is not easy.'

An oil sketch shows Churchill in one of his characteristic moods, abstracted and brooding. After lunch one day he had agreed to be photographed by Felix Man, at the same time as he was dictating letters to his secretary; he had gone over to the window and, as the sun was low, his skin seemed transparent, an effect sensitively portrayed by Sutherland An oil sketch shows Churchill in one of his characteristic moods, abstracted and brooding. After lunch one day he had agreed to be photographed by Felix Man, at the same time as he was dictating letters to his secretary; he had gone over to the window and, as the sun was low, his skin seemed transparent, an effect sensitively portrayed by Sutherland

Graham Sutherland, by John Hayes, Phaidon Press, 1980

SEE:

- Graham Sutherland's Winston Churchill (1954)

by Jonathan Jones Guardian Unlimited, November 3, 2001

- Forerunner of lost Churchill portrait goes on show

by John Ezard, Guardian, Thursday, July 1, 1999

- Sutherland to Beaverbrook about the Churchill Portrait

'...The final form that the portrait took stemmed entirely from Churchill. He asked the first morning - "How will you paint me - as a cherub or the Bull Dog?" I replied "It entirely depends what you show me, sir". Consistently - except for the afternoon in which the foundations of the so-called "Hecht portrait" were laid (when he was in a sweet & melancholy reflective mood) he showed me the Bull Dog!! For better of [sic] for worse, I am the kind of painter who is governed entirely by what he sees. I am at the mercy of my sitter. What he feels or shows at the time I try to record. At this time there were unfortunate complications of a political nature. Repeatedly I was told "They (meaning his colleagues in the government) want me out" "But" (and this is a paraphrase of the actual conversation) "I'm a rock" and at that the face would set in lines & the hands clutch the arms of the chair. No one, I can say categorically, influences me in my renderings. The only danger to me sometimes is the charm of the sitter. Churchill often showed me the greatest charm & could not have been kinder. Non [sic] the less he was self concious [sic] & ill at ease during the actual times of sitting. I was seduced by his charm at other times & wanted so much to please him. But I draw what I see; & 90% of the time I was shown precisely what I recorded...I would not like to go down into the small history I may create as a person who deliberately or unconsciously malformed a face at the dictate of another...' '...The final form that the portrait took stemmed entirely from Churchill. He asked the first morning - "How will you paint me - as a cherub or the Bull Dog?" I replied "It entirely depends what you show me, sir". Consistently - except for the afternoon in which the foundations of the so-called "Hecht portrait" were laid (when he was in a sweet & melancholy reflective mood) he showed me the Bull Dog!! For better of [sic] for worse, I am the kind of painter who is governed entirely by what he sees. I am at the mercy of my sitter. What he feels or shows at the time I try to record. At this time there were unfortunate complications of a political nature. Repeatedly I was told "They (meaning his colleagues in the government) want me out" "But" (and this is a paraphrase of the actual conversation) "I'm a rock" and at that the face would set in lines & the hands clutch the arms of the chair. No one, I can say categorically, influences me in my renderings. The only danger to me sometimes is the charm of the sitter. Churchill often showed me the greatest charm & could not have been kinder. Non [sic] the less he was self concious [sic] & ill at ease during the actual times of sitting. I was seduced by his charm at other times & wanted so much to please him. But I draw what I see; & 90% of the time I was shown precisely what I recorded...I would not like to go down into the small history I may create as a person who deliberately or unconsciously malformed a face at the dictate of another...'

- An Extract from a Current Artists' Lives Recording:

The painter and collagist, Elsbeth Juda, moved from Germany to London in 1933 with her husband Hans. . . they built up a distinguished collection of contemporary art and became close friends with many of the artists they collected. Elsbeth's two edited extracts from the NLSC recording recall how Sigmund Freud saved Elsbeth's life and how she and Hans were twice involved in almost saving Graham Sutherland's portrait of Winston Churchill for posterity:

"The Churchill portrait was for his eightieth birthday, and Sutherland was working away and showed Churchill only ever one oil sketch which was Churchill in his garter robes (which went straight to the Beaverbrook Museum in New Brunswick, Canada). And so Churchill obviously thought he was going to be painted in his garter robes [but] he wore his zoot suit for the sittings and never saw anything while Graham was working on the portrait, which made him a little irritable. And Sutherland had miserable sittings because Churchill had had a stroke and also drank heavily at lunch. Finally, during the session, Sutherland would say, 'A little more of the old lion, sir' and he'd sit up and then flop after a minute. And so Graham was desperate."

"The week before it was finished, Graham said, 'Elsbeth, could you spare the time to come down to Westerham (where Churchill was living) and do a few photographs for me because he's simply folding up every time.' I was happy to do that. I went and took a whole set of photographs, which are now at the National Portrait Gallery, which are exactly like the portrait - the hand with the cigar, everything. And Churchill was enchanting, being photographed."

"Anyway, the painting was done, and Graham took the risk-limiting step and asked Kenneth Clark, who was a great admirer of Sutherland, to look at the painting. K. Clark went to the White House with Lady Churchill and pronounced it a masterpiece, so all was set and fine. Well, [at the public unveiling] when Churchill pulled the velvet cord and saw himself in his zoot suit, slumped, with his feet cut off, he freaked out. He never referred to it again. And Graham rang up later that afternoon and said, 'Oh Hansie, I can't bear it. He's not having it. He doesn't want it. He hates it. What am I going to do? I can't afford to spend all�.' Hans said, 'Just calm down, Graham. Send it to us.' And so it was delivered and we had it in our studio living room and it looked very nice on an easel. And we photographed it. We were going to pay Sutherland the going rate."

"Three days later, another phone call [from Sutherland]. 'I'm not allowed to give it to you, it's got to go back to Hyde Park Gardens [Churchill's London home]. So we delivered it back. And that's where she [Lady Churchill] burnt it. He was so distressed, having it in the house, so she took it down, chopped it up and put it in the boiler."

"Anyway, twenty years later, fifteen years later, the Sunday Times rings. They said, 'Elsbeth, you've got these Churchill photographs, would you send them around, we'll send a messenger?' I said, 'Not so fast.' Because it was a privileged occasion, they belonged to Graham Sutherland as much as me. 'Have you asked Graham?' 'Oh, yes, we've asked him. He's at the Connaught.' So I rang the Connaught and Graham said, 'Yes, I'm here. I'd quite like to see them [the photos].' So I went over there and he said, 'Do you know they are terrific, because the Sunday Times has asked me to repaint the portrait for a huge fee. Can I keep these photographs?' And so he kept them. And he was going to do the portrait for the Sunday Times for some anniversary. But he didn't live long enough to do it. So that's the end of the Churchill portrait."

Source: NLSC Newsletter

|

|

IMAGES ON LINE

- Graham Sutherland (National Portrait Gallery)

- Image: Self Portrait, 1945, pencil

click to enlarge

- Image: Thorn Head, 1946, oil on wood

- Image: Study of Lord Beaverbrook, 1950, oil on canvas

- Publish and be hanged by Laura Cumming. Observer. July 11, 1999

From Sargent to Freud: Modern British Art in the Beaverbrook Collection ". . includes paintings that Beaverbrook loved - by Sickert, Nash and Hitchens - and several that he admired but probably loathed, notoriously his own portrait by Graham Sutherland.

This painting from the Beaverbrook collection . . . is as insidiously nasty as anything Sutherland ever produced. Squared up from photographs and drawings, it crawls over the magnate's face like a bluebottle examining dung. Beaverbrook looks like a raddled toad, pickled in the purple, green and ochre of Sutherland's palette. No matter how broadly he smiles, the squinting, sightless eyes give a narrow cunning to the face. The portrait was a birthday present from the Daily Express and Beaverbrook was tactful in receipt: 'It's an outrage - but it's a masterpiece!'

- Image: William Maxwell Aitken 1st Baron Beaverbrook, 1951

sketchbook drawing

- Image: 1st Baron Beaverbrook, 1952, oil/canvas

- Photograph: Lord Beaverbrook

- Image: Maugham Sketchbook

- Image: William Somerset Maugham, 1952, lithograph

- Image: Somerset Maugham, 1953, black chalk, pencil & gouache

- Image: Somerset Maugham, 1953, black clalk

- Image: Sir Winston Spencer Churchill, 1954, oil/canvas

- Winston Churchill, 1954, oil/toned canvas

- Winston Churchill, 1954, chalk

- Winston Churchill (hand), 1954, pen & ink and pencil

- Image: Kenneth Clark, c.1962-64, oil/canvas

- Image: Kenneth Clark (profile), 1963-64, oil

- Image: Charles Clore, 1967, pencil & crayon

- Image: Self Portrait, 1977, oil/canvas

- Image: Milner Gray, 1979, oil

- Google Image Search

|

|

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Sutherland: Christ in Glory in The Tetramorph The Genesis of the Great Tapestry in Coventry Cathedral; text edited by Andrew Revai; The Pallas Gallery, London, 1964

- Portraits by Graham Sutherland; John Hayes; National Portrait Gallery, 1977

- The Art of Graham Sutherland; by John Hayes; Alpine Fine Arts Collection, Ltd./Phaidon Press, 1980

- Graham Sutherland: A Biography; by Roger Berthoud; Faber and Faber, London, 1982

- Graham Sutherland; Ronald Alley; The Tate Gallery, London, 1982

|

|

LINKS

- Sutherland's Portrait of Churchill

- Francis Bacon

- School of London

- The Colony Room

- Graham Sutherland Prints

- Sutherland's "Crucifixion"

- Imperial War Museum Art Collection

- Beaverbrook Art Gallery (project)

- Galerie d'art Beaverbrook

The Gallery is internationally known for its outstanding collection of British paintings. . . Modern British art is represented by the work of Augustus John, Sir Stanley Spencer, Walter Richard Sickert and Graham Sutherland, including Sutherland's preparatory sketches for his famous portrait of Winston Churchill.

- National Gallery of Canada

- MO-Moderna Gallery

- Coventry Cathedral Images

- University of Lethbridge Art Gallery

- Art Masterpiece Collection

Jim's Fine Art Collection: It is my hope to provide quality scans of works from a wide array of painters and sculptors, from Europe to the Americas, and from Africa to Australia and Asia. Included are works from pre-historic cave paintings to contemporary artists. A little something for everyone, you might say. At last count, 4,539 works from 351 artists are in the collection. More than 3,500 remain to be added, as Ol' Jim finds available free time between working and sleeping.

- Malaspina.com: GrahamSutherland

top

Copyright © 2001 - PantherPro WebSites, USA

|

GRAHAM VIVIAN SUTHERLAND was born on August 24, 1903 in London, the son of a lawyer who later became a civil servant. He was primarily a painter of imaginative landscapes, portraits and still lifes. From 1920 to 1925 he studied at Goldsmiths' College School of Art, specializing in printmaking. In 1926 Sutherland converted to Roman Catholicism. The following year he married Kathleen Barry. He taught at Kingston School of Art, Chelsea School of Art, Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford, and at Goldsmiths', until after World War II when he decided to become a full-time painter.

GRAHAM VIVIAN SUTHERLAND was born on August 24, 1903 in London, the son of a lawyer who later became a civil servant. He was primarily a painter of imaginative landscapes, portraits and still lifes. From 1920 to 1925 he studied at Goldsmiths' College School of Art, specializing in printmaking. In 1926 Sutherland converted to Roman Catholicism. The following year he married Kathleen Barry. He taught at Kingston School of Art, Chelsea School of Art, Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, Oxford, and at Goldsmiths', until after World War II when he decided to become a full-time painter. The controversial portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, which Churchill himself hated because he said it 'makes me look half-witted' and which was destroyed (on the order of Mrs. Churchill) out of anger only a year or two after its completion, was commissioned in 1954 by past and present members of the House of Lords and House of Commons, and presented to the great statesman as a celebration of his eightieth birthday at a ceremony in Westminster Hall on November 30, 1954. Although Churchill would have preferred to have been painted in his robes as Knight of the Garter, the All-Party Committee has specified that he should be represented as the House of Commons had always known him, and the spotted bow-tie, black coat and waistcoat and striped trousers in which Sutherland painted him were indeed the dress familiar to every one of Churchill's parliamentary colleagues. At the first sitting Churchill asked Sutherland: 'How will you paint me, as a cherub or the bull dog?' 'He showed me a bulldog so I painted a bulldog.' Though the picture could never have been other than a portrait of an old man. . . Sutherland conveyed to the full the distinction and tenacity of the elder statesman. . . The pose is firm, the weight of the form massive, and Churchill's legs seem like mighty columns precisely because they have been truncated. 'The tyranny of the edge of the canvas, where to end the movement, is always a great problem with any kind of painting. . . Where to make the cut between the knee and the foot is not easy.'

The controversial portrait of Sir Winston Churchill, which Churchill himself hated because he said it 'makes me look half-witted' and which was destroyed (on the order of Mrs. Churchill) out of anger only a year or two after its completion, was commissioned in 1954 by past and present members of the House of Lords and House of Commons, and presented to the great statesman as a celebration of his eightieth birthday at a ceremony in Westminster Hall on November 30, 1954. Although Churchill would have preferred to have been painted in his robes as Knight of the Garter, the All-Party Committee has specified that he should be represented as the House of Commons had always known him, and the spotted bow-tie, black coat and waistcoat and striped trousers in which Sutherland painted him were indeed the dress familiar to every one of Churchill's parliamentary colleagues. At the first sitting Churchill asked Sutherland: 'How will you paint me, as a cherub or the bull dog?' 'He showed me a bulldog so I painted a bulldog.' Though the picture could never have been other than a portrait of an old man. . . Sutherland conveyed to the full the distinction and tenacity of the elder statesman. . . The pose is firm, the weight of the form massive, and Churchill's legs seem like mighty columns precisely because they have been truncated. 'The tyranny of the edge of the canvas, where to end the movement, is always a great problem with any kind of painting. . . Where to make the cut between the knee and the foot is not easy.' An oil sketch shows Churchill in one of his characteristic moods, abstracted and brooding. After lunch one day he had agreed to be photographed by Felix Man, at the same time as he was dictating letters to his secretary; he had gone over to the window and, as the sun was low, his skin seemed transparent, an effect sensitively portrayed by Sutherland

An oil sketch shows Churchill in one of his characteristic moods, abstracted and brooding. After lunch one day he had agreed to be photographed by Felix Man, at the same time as he was dictating letters to his secretary; he had gone over to the window and, as the sun was low, his skin seemed transparent, an effect sensitively portrayed by Sutherland  '...The final form that the portrait took stemmed entirely from Churchill. He asked the first morning - "How will you paint me - as a cherub or the Bull Dog?" I replied "It entirely depends what you show me, sir". Consistently - except for the afternoon in which the foundations of the so-called "Hecht portrait" were laid (when he was in a sweet & melancholy reflective mood) he showed me the Bull Dog!! For better of [sic] for worse, I am the kind of painter who is governed entirely by what he sees. I am at the mercy of my sitter. What he feels or shows at the time I try to record. At this time there were unfortunate complications of a political nature. Repeatedly I was told "They (meaning his colleagues in the government) want me out" "But" (and this is a paraphrase of the actual conversation) "I'm a rock" and at that the face would set in lines & the hands clutch the arms of the chair. No one, I can say categorically, influences me in my renderings. The only danger to me sometimes is the charm of the sitter. Churchill often showed me the greatest charm & could not have been kinder. Non [sic] the less he was self concious [sic] & ill at ease during the actual times of sitting. I was seduced by his charm at other times & wanted so much to please him. But I draw what I see; & 90% of the time I was shown precisely what I recorded...I would not like to go down into the small history I may create as a person who deliberately or unconsciously malformed a face at the dictate of another...'

'...The final form that the portrait took stemmed entirely from Churchill. He asked the first morning - "How will you paint me - as a cherub or the Bull Dog?" I replied "It entirely depends what you show me, sir". Consistently - except for the afternoon in which the foundations of the so-called "Hecht portrait" were laid (when he was in a sweet & melancholy reflective mood) he showed me the Bull Dog!! For better of [sic] for worse, I am the kind of painter who is governed entirely by what he sees. I am at the mercy of my sitter. What he feels or shows at the time I try to record. At this time there were unfortunate complications of a political nature. Repeatedly I was told "They (meaning his colleagues in the government) want me out" "But" (and this is a paraphrase of the actual conversation) "I'm a rock" and at that the face would set in lines & the hands clutch the arms of the chair. No one, I can say categorically, influences me in my renderings. The only danger to me sometimes is the charm of the sitter. Churchill often showed me the greatest charm & could not have been kinder. Non [sic] the less he was self concious [sic] & ill at ease during the actual times of sitting. I was seduced by his charm at other times & wanted so much to please him. But I draw what I see; & 90% of the time I was shown precisely what I recorded...I would not like to go down into the small history I may create as a person who deliberately or unconsciously malformed a face at the dictate of another...'