The Imposition of the Embargo Act

Internal Conflict Arises and External Conflict Does Not Diminish

In 1807 President Jefferson convinced the Congress to pass the "Embargo Act" which declared: "[T]hat an embargo be, and hereby is laid on all ships and vessels in the ports and places within the limits or jurisdiction of the United States, cleared or not cleared, bound to any foreign port or place; and that no clearance be furnished to any ship or vessel bound to such foreign port or place, except vessels under the immediate direction of the President of the United States...[and] That during the continuance of this act, no registered, or sea letter vessel, having on board goods, wares and merchandise, shall be allowed to depart from one port of the United States to any other within the same, unless the master, owner, consignee or factor of such vessel shall first give bond, with one or more sureties to the collector of the district from which she is bound to depart, in a sum of double the value of the vessel and cargo, that the said goods, wares, or merchandise shall be relanded in some port of the United States, dangers of the seas excepted, which bond, and also a certificate from the collector where the same may be relanded, shall by the collector respectively be transmitted to the Secretary of the Treasury." (MacDonald, No. 27).

Since the "Embargo Act" (MacDonald, No. 27) prevented importation and exportation it hurt American industries who relied on foreign markets. The only industry to prosper under the "Embargo Act" (MacDonald, No. 27) was manufacturing because all Americans were forced to buy domestic products.

|

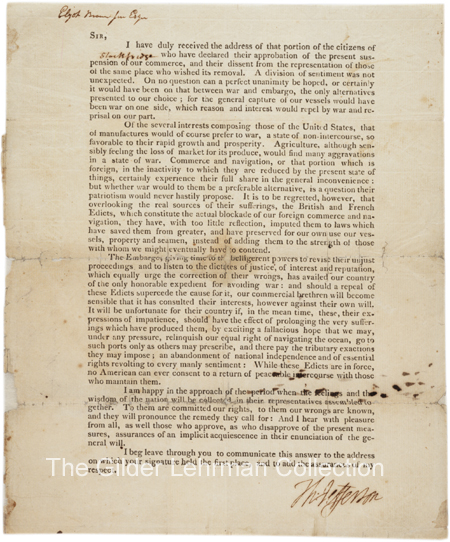

This economic pressure resulted in a disgruntled populace. President Jefferson acknowledged this dissatisfaction in a letter to Elijah Brown, Jr. Esq. saying: "I have duly received the address of that portion of the citizens of Stockbridge [Massachusetts] who have declared their approbation of the present suspension of our commerce, and their dissent from the representation of those of the same place who wished its removal. A division of sentiment was not unexpected. On no question can a perfect unanimity be hoped, or certainly it would have been on that between war and embargo, the only alternatives presented to our choice...Of the several interests composing those of the United States, that of manufactures would of course prefer to war, a state of non-intercourse, so favorable to their rapid growth and prosperity. Agriculture, although sensibly feeling the loss of market for its produce, would find many aggravations in a state of war. Commerce and navigation, or that portion which is foreign, in the inactivity to which they are reduced by the present state of things, certainly experience their full share in the general inconvenience: but whether war would to them be a preferable alternative, is a question their patriotism would never hastily propose." He went on to defend the Embargo Act declaring: "The Embargo, giving time to the belligerent powers to revise their unjust proceedings and to listen to the dictates of justice, of interest and reputation, which equally urge the correction of their wrongs, has availed our country of the only honorable expedient for avoiding war: and should a repeal of these Edicts supersede the cause for it, our commercial brethren will become sensible that it has consulted their interests,

| ("Thomas Jefferson�s defense") |

however against their own will...While these Edicts are in force, no American can ever consent to a return of peaceable

intercourse with those who maintain them." ("Thomas Jefferson�s defense").

{Next}

{Events Leading to the Embargo}

{Post-Embargo Actions }

{Conclusions}

{HOME}