|

|

|

A BIOGRAPHY

<

|

|

|

|

For the benefit of the people of France, this biography was graciously translated in its entirety into French by Dr. Philippe Bodin, Ph.D., Deputy Mayor of Guilers, France, the city where Maurice O'Connell's body was recovered by the U.S. Army Graves Registration Service. The people of New Clover Creek Baptist Church and the Family of Maurice F. O'Connell express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Bodin for this very noble undertaking. On October 15, 1998, Kentucky Governor Paul E. Patton appointed Philippe a Kentucky Colonel, in recognition of his translation and for his kind assistance to the O'Connell family. |

A follow-up to this story was printed in the November 12, 1998, edition of the Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer. To read the story, click here.

On May 27, 1996, Congressman Ron Lewis (R., Ky.) posthumously awarded military decorations to the family of Maurice F. O'Connell, during the dedication of the church's library. The following is a biography of O'Connell and his contributions to the World War II war effort.

As I write these words, I am awestruck by the thought that a young man gave his life in order that others might live their lives more freely. This is the story of an unsung hero. I became interested in Maurice Francis O'Connell while I was writing A History of New Clover Creek Baptist Church. Maurice's story tore at my heart. This twenty-year-old, who was partly a man, partly a boy, was killed by Nazis who served an evil regime. He was buried for almost four years in France, thousands of miles away from home, leaving several family members who never knew what happened to him. His grieving mother and father learned nothing more than that he died somewhere in France on August 27, 1944.

In addition to the freedoms which are now secure in the United States, there can be no doubt that the Allied victory in World War II ushered in the economic stability of the 1950's and 60's. The lifestyles which all Americans now savor are in no small part attributable to the fact that the Allies won this war.

Shielded by the passage of time and shackled by a lack of understanding, too few people really remember Maurice or comprehend the supreme sacrifice he made for his fellow countrymen. Freedom is not free. While soldiers are often attracted to military service for the honor and glory they perceive, the benefactors of their services are often forgetful and unappreciative. It is dubious that any French citizen is aware of Maurice's particular contribution to the liberation of France and Europe, but even less excusable are the American counterparts, who knew and loved, yet forgot about Maurice O'Connell. Yet without such sacrifices, the Allies could not have contained the evils of Nazi aggression.

Perhaps what is most striking about the young soldier who so bravely fought and gave his life for his country is that Maurice was a devoted Christian, whose service to his church can be documented in several ways. While Hubert Wayne Miller, a former member of New Clover Creek Baptist Church, gave his life during the Vietnam War, Maurice O'Connell was the only active member of the church to have given his life in combat.

Maurice's mother died March 17, 1982, and his father died March 18, 1987. As you read this biography, bear in mind that you are reading mostly recently-discovered material, because neither of Maurice's parents knew during their lifetimes any details as to what happened to their son. Despite efforts repeatedly made by Maurice's widow and parents to acquire information, the U.S. Army remained silent as to the details of his death, partly because communication in the 1940's was less than efficient and partly because no reports described the details of his death. Since the war, however, several official records have been opened for public inspection. Several soldiers who survived the war have chronicled their experiences in historical publications. One book, The Long Line of Splendor, 1742-1992, is a history of the 116th Infantry Regiment, written by Rev. John W. Schildt. Another is 29 Let's Go!, a history of the 29th Infantry Division, written by Joseph H. Ewing. With the permission of both authors, these publications have been extensively quoted in this biography and have served as significant resources in our quest to determine what happened to Maurice in his final days of battle.

What has been attempted in this sketch is to chronologically assimilate several sources of information so that the reader might have a true picture of Maurice O'Connell's life and his contributions to mankind. Since thorough histories of World War II are already abundant, I have avoided duplicating general information. Instead, the focus of this book is upon Maurice's personal contribution to the war effort.

This booklet was written to the Glory of God and to preserve forever the contributions of an American hero. Even in his death, Maurice O'Connell inspires us to appreciate our country. I think he knows that we are remembering him, in our own little way.

So this is for you, Maurice. I know you would be proud. Maybe you can still teach us a lesson in bravery and patriotism.

Maurice F. O'Connell was born June 30, 1924, the son of Alfred Francis and Beulah Marie (Keenan) O'Connell. His parents married at St. Romuald Roman Catholic Church, in Hardinsburg, Kentucky, on November 16, 1921, and they set up housekeeping with Ernest Payne, a bachelor who lived on a farm between McQuady and Tar Fork on what is now Kentucky Highway 625 in rural Breckinridge County. Maurice was born in Payne's house. The farm is presently owned by Sherman and Margaret Ann Taul.

Alf was a farmer, and Marie was a housekeeper. Like all of the Keenan sisters, Marie was known as an excellent cook, who loved to prepare country-style meals and bake cakes and pies. Maurice grew up knowing the best of country cooking.

Maurice's paternal grandparents were Dan and Rose (Askin) O'Connell. His maternal grandparents were William Lawrence Keenan and Mary Elizabeth (Mingus) Keenan. Both parents were descended from Irish immigrants. Thomas O'Connell, Maurice's great grandfather, came to America through New York City from County Cork, Ireland. Patrick Keenan, Maurice's great-great-great grandfather, immigrated from Inishkeen Parish, Drumboat, County Monaghan, in the Ulster Province of Ireland. Maurice held a special place in the hearts of William and Mary Keenan, for he was their first-born grandson.

On August 9, 1924, Maurice's parents took their 40-day-old baby to St. Mary of the Woods Roman Catholic Church in McQuady, where Father John F. Knue baptized him.

Before Maurice's brother Charles Preston was born on August 9, 1926, Alfred and Marie moved to Pinchecoe, to a house owned by Maurice's maternal grandparents. Maurice's great grandparents Patrick Henry Keenan and Emily Eliabeth (Reno) Keenan once lived in this house. Pinchecoe was a very small community which no longer exists. It was situated near the border of Breckinridge and Hancock Counties, accessed by what is now called the LaMar Ryan-Hickory Ridge Road.

A short time after Preston's birth, the O'Connell family again moved, this time to the Ben Bates house, across Kentucky Highway 105 from the barn on what is now known as the C. B. Bates farm. There, Maurice's youngest brother Walter Keenan was born on January 6, 1930. A fire in the 1960's destroyed the house, injuring Paul Mattingly and C. B. Bates who were both friends of the family.

The O'Connells remained at the Ben Bates house for about two years before they moved to another house, about a half mile west and across the highway from where Maurice's grandfather William Lawrence Keenan lived. It was in this house that Maurice spent the greater portion of his life, from about 1932 until he was called into the military service in 1943. This house was also nextdoor to his Uncle Walter and Aunt Ruby O'Connell. Walter was a brother to Maurice's father, Alf; Ruby was a sister to Maurice's mother, Marie. Their daughter, Rosemary, was Maurice's double first cousin.

As small children, Maurice and his two brothers frequently played around the farm. Since the two O'Connell sisters sewed quilts for the needlecraft studio in Hardinsburg, the boys used wire to make little toys out of the empty wooden thread spools. They loved to play in the dirt. Having few other toys, they played with stick horses, and they made a pet of a young raccoon, which they named "Coonie."

Also nextdoor lived Maurice's playmate, John Walter "Junior" Brickey. These two boys became an inseparable pair, even after World War II broke out.

Maurice liked to hunt and fish, and as he grew older, he enjoyed helping his dad work on the farm. They raised tobacco and corn. The family owned a few horses, which they relied upon for transportation, and they raised a few hogs and chickens. Marie raised turkeys and, in fact, had so many that she contracted with Roy Jackson to sell some of them during the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. Occasionally, Maurice and his dad would finish their chores, so Maurice sometimes had time to work for his Grandpa Keenan on his farm.

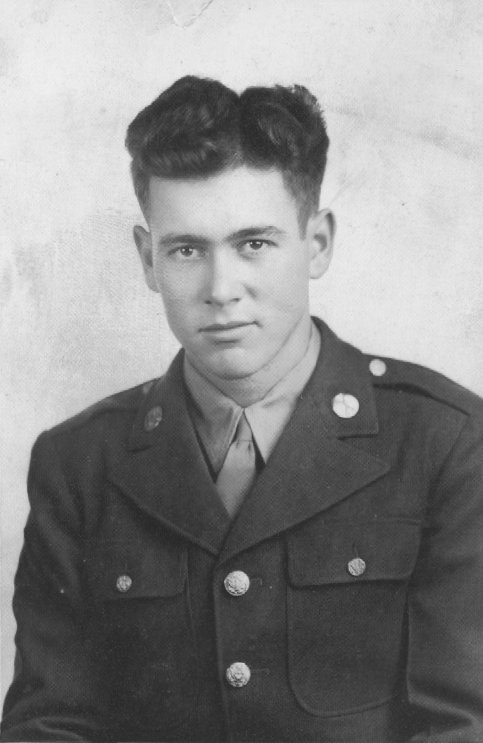

When Maurice grew to manhood, he stood only about five feet, six inches tall. Although somewhat quiet and reserved, he was fun-loving and jovial. He had a good sense of humor, and he loved to play pranks on his relatives and friends. Standing on his head was one of his favorite stunts. Having a pleasant personality, he was a well-thought-of boy. He was a devoted Christian; everyone who knew him commended him by simply saying, "He was just a good boy."

In the fall of 1934, some individuals in the Clover Creek Community decided to build a church. The congregation of the old Clover Creek Baptist Church had disbanded, leaving a number of individuals in the area without a convenient church to attend. In addition, the Cave Spring Baptist Church, in the Tar Fork Community, had also disbanded, leaving an empty building available to be moved to a new location. Consequently, in November of 1934, when Maurice was only ten years old, the New Clover Creek Baptist Church was begun. The founding members arranged to move the Cave Spring building to its present location. The old church was dismantled; each board was numbered and then moved by a wagon team to the present site. The dedication of the new sanctuary was held June 30, 1935, on Maurice's eleventh birthday.

It is difficult to specify at what time the O'Connells began attending New Clover Creek, although older church members remember they regularly attended soon after the formation of the church. Being a Roman Catholic, Alf only occasionally accompanied his wife and children to church. The small congregation needed a pianist, and Marie O'Connell could play most of the songs from the Broadman Hymnal. As a child, Marie had received piano lessons from a music teacher who lived with her family while school was not in session. Thus, shortly after the formation of New Clover Creek, Marie, her ten-year-old son Maurice, her eight-year-old son Preston, and her four-year-old son Keenan, began attending the new church.

Although she played the piano regularly at New Clover Creek, Marie did not become a member of the church for about six years. Evangelist Alvin Furrow came to the church for a two-week revival, which began October 14, 1940. Six individuals made professions of faith, including Marie and her two sons Maurice and Keenan. On the last day, October 28, a baptismal service was conducted by Bro. William Varble, pastor, and Maurice converted from Roman Catholicism and became a Southern Baptist. The baptism was conducted in the Beechfork Branch of Clover Creek, on the farm now owned by Keenan O'Connell, not far from the Highway 992 bridge.

After they had joined the church, Marie and her two sons qualified to serve as church officers. During the 1941 calendar year, Marie served as church treasurer. For fourteen years, from May 17, 1941, until July 8, 1955, she served as church clerk. On November 16, 1941, at the age of seventeen, Maurice was elected secretary of the Sunday School, to serve for the 1942 calendar year. This little job required him to keep track of the weekly attendance of Sunday School members and to record the Sunday School offering.

From the first through the eighth grades, Maurice attended Taul Schoolhouse, an elementary school once located where the home of Ernie and Carol Dubree is presently. His teachers there included Alice Hardin, a Miss Jarboe, Evelyn DeHaven, and Tommy Miller (later Coke). Tommy Miller taught at the school for three academic years, 1934-1937. She remembered Maurice as a perfectly behaved young man who was both intelligent and serious-minded with his studies. Preston, she humorously recalls, was a somewhat more mischievous boy who sometimes embarrassed his older brother.

Many youngsters in remote parts of the county could not attend Breckinridge County High School, which was in Hardinsburg over five miles away from the O'Connell home. Fortunately for Maurice, a school bus ran from the rock quarry, about a mile from his home, to Hardinsburg. Maurice could walk to the school bus stop, catch the bus, and make the daily ride to Hardinsburg to attend school there. He studied for a couple of years in high school, although he did not obtain his diploma.

Maurice first met his wife, Helen Wilson Taul, at the home of Hubert and Hazel Miller, in the fall of 1941. Helen was the daughter of Patrick S. and Pearl (Lyons) Taul of McQuady. She arrived at the Miller house in the company of her friend, Charlotte Shrewsberry (later Taul).

The next Monday at school, during a study hall in the high school auditorium, Maurice sat down beside Helen. Shortly afterward, they began to date, and they continued to see one another regularly until he was inducted into the army. At first, Helen was shy about their relationship, but in many ways, Maurice flattered Helen.

On his many visits to McQuady to see Helen, Maurice rode his horse down an old road that connected what is now Kentucky Highway 992 with Highway 105, near McQuady. One day, Maurice told her that he loved her and then insisted that she tell him that she loved him too. "I know that you love me," he asserted. "Say it," he insisted. Once she admitted that she loved him, the couple seemed to know they were destined to marry. From one of his letters, it appears that sometime in early January of 1943, Maurice told his parents that he wanted to marry Helen.

World War II broke out on December 7, 1941, when Japanese airplanes bombed American ships docked at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, nearly destroying the Pacific Fleet. Within a few hours, Congress declared war on Japan. Four days later, Congress declared war on Germany and Italy. Thus began the struggle which would impale a nation and destroy the lives of 405,399 Americans.

At the time of the attack, Maurice was only seventeen years of age. While the possibility of being drafted seemed imminent, in other ways, it seemed remote. Maurice received a draft notice from the Breckinridge County Draft Board probably in late 1942. He later regretted that he did not voluntarily enlist, which would have permitted him some choice of assignments, for on January 11, 1943, Maurice wrote Helen, "The more I thnk about it, the more I wish that I had joined the Coast Guard when Dallas [Taul] did. I believe that if I could have passed the exam, I would have liked it as well as the Navy." What remained unwritten in the letter was the fact that a position with the Coast Guard would have been less dangerous than being in the infantry. Maurice was inducted into the United States Army on March 24, 1943, and was directed to report for duty on March 31.

Like most soldiers from Breckinridge County, Maurice was first sent to Camp Benjamin Harrison for the army's initial formalities. By July of 1943, the 262nd Infantry was transferred to Camp Joseph T. Robinson, near Little Rock, Arkansas. During his training there, in July or August of 1943, Maurice broke his left arm, and he was hospitalized at Camp Robinson Station Hospital, Ward 5103, with his arm in a cast.

A friend, Hardinsburg soldier James O. Gibson, paid a visit to Maurice in the hospital and told him that only about twenty-six men from their company remained in the United States; the rest had been shipped overseas to prepare further for war. Maurice thought that he would have made corporal if he had gone overseas at the time he was supposed to leave.

The stay in the hospital was full of fun. In a letter to his Aunt Irene Keenan Taul, Maurice wrote:

Talk about getting into meaness [sic], I've been getting there since I got into this ward. Anywhere from tearing up beds to giving hot feet. The other day, the Sergeant gave me a loaded cigarette, then last night he tied my bed in knots. I'm trying to figure something up a little worse than what he generally does to me, but it's pretty hard to do.

Even while hospitalized with a broken arm, Maurice managed to correspond with Helen, and he finally asked her to come to Arkansas so they could marry. She agreed to marry him and then made arrangements to travel to Arkansas.

Helen later considered the broken arm a blessing in disguise because it enabled her to spend a little more time with Maurice than she otherwise would have had.

In mid-September, 1943, while Maurice was still hospitalized, his fiancé, Helen Taul, boarded a bus at the Hardinsburg Greyhound Station and headed west toward Little Rock. Helen had never been further from home than Louisville, but she was not afraid of making the journey by herself. The trip took all of one day, all of one night, and part of the next day. She arrived in Little Rock one afternoon, and Maurice was still in the hospital. Helen was inclined to suffer from motion sickness. Using an old-fashioned remedy, she sucked on a lemon during the journey to avoid becoming ill. Maurice made arrangements for Helen to stay in a local resident's house until the wedding.

At Maurice's request, the physicians at the hospital agreed to grant him leave for one day, so he could marry. On September 21, 1943, Maurice and Helen then visited the courthouse in Little Rock, where they obtained a marriage license from Pulaski County Clerk L. A. Mashburn. They then traveled to a small Baptist church in Little Rock, where Rev. Charles E. Lawrence married them in a quiet ceremony. Their friends, Ted and Helen Mattingly, of McQuady, were witnesses. Hardly anyone else attended.

Someone snapped a photograph of the new couple, but Maurice hid his casted arm behind his new bride. On his right hand, he wore her 1943 Breckinridge County High School class ring. They spent their wedding night at the home of a couple named Honeycutt, but the doctors refused to allow Maurice to return home until the arm cast was removed. Helen remained with the Honeycutts until then, and when Maurice was released from the hospital, they remained with the Honeycutts only a brief period of time.

A few weeks after Maurice was able to leave the hospital, the new couple moved into an apartment in Little Rock, owned by a couple named Jones. During their stay, both Maurice's mother and Helen's mother traveled to Little Rock for separate visits.

When they married, Maurice was paid $50.00 per month. Helen took a job with a factory that made Sears clothes for children. Later, she worked in a factory that made army clothes.

Furloughs from the United States Army were hard to come by, so the O'Connell family in Hardinsburg did not expect a visit from Maurice during Christmas of 1943. Much to the chagrin of his parents, Maurice and Helen showed up at their doorstep just before Christmas Day. With her son handsomely decked out in his U.S. Army uniform, Marie beamed with pride. During the Christmas holidays, they visited a number of family members, including his grandparents, William and Mary Keenan. The visit seemed too short, however, and Maurice and Helen had to return to Little Rock, so he could continue his training with the Army.

In the spring of 1944, Maurice received his last furlough to visit Breckinridge County. From May 2 to 11, Maurice and Helen returned home. Of course, no one realized that he would never again see his family. During one of the several visits with family, Maurice's kindness and attention charmed his eight-year-old cousin Jeanette Ryan (later Richards).

Not long after they returned to Little Rock from the furlough, Helen miscarried with a very premature child. Although the loss of the baby was a traumatic experience for both Helen and Maurice, they hoped to have another child.

Maurice received word that the 262nd Infantry would soon be transferred to Camp Rucker, near Montgomery, Alabama. On June 1, 1944, Maurice moved to Montgomery, leaving Helen in Little Rock. While enroute, the train in which the 262nd Infantry was riding wrecked, but Maurice was not injured.

Helen remained in Little Rock for a few days while Maurice searched for an apartment in Montgomery. The best place that he could find for the two of them to live in was an upstairs room in a local woman's house. The landlady separated the room with bed sheets, and three other couples lived in the same room. Fortunately, the O'Connells stayed there for only a few nights before they moved into a trailer in the backyard. With no air conditioning, the temperature in the trailer sometimes rose to a sweltering 120 degrees. Despite the heat, Helen was happy but felt that the Montgomery landlady was selfish and unaccommodating.

Under great secrecy, General Dwight D. Eisenhower set June 5, 1944, as the date for the Great Invasion of Europe. However, inclement weather prohibited the ships from sailing that day, so the invasion was delayed until June 6. Particularly significant for young Maurice O'Connell were the activities of the 116th Infantry Regiment. Because this regiment lost so many men on D-Day, the army assigned numerous replacements, and Maurice was one of them.

The young O'Connell couple was still in Montgomery on D-Day. News of the invasion disturbed both of them, as each realized that Maurice might be called off to Europe. Hearing of the invasion, Helen and one of her friends, the wife of another soldier, walked to the base chapel to pray for the safety of the troops.

The army quickly informed Maurice, however, that he would have to go overseas as a replacement soldier. He only knew he would have to leave Montgomery in mid-June and travel to Ft. George G. Meade, in Maryland. From there, he would be shipped overseas to an unspecified destination.

Shortly before Maurice left Montgomery, Helen packed her belongings and boarded a Greyhound Bus, so she could return to Kentucky and live with her parents in McQuady until Maurice's service in the war came to an end. Maurice accompanied his young wife to the bus, and she began to cry. "Now, don't you cry," Maurice told her. "So I didn't cry," she later explained. Maurice walked her to the steps of the bus and there kissed her good bye, for he could not board the bus without a ticket. As the bus began to depart, Helen looked forward from her seat to see Maurice again before the bus left, but he was not there. She thought that Maurice had begun to cry and that he had returned inside the depot so she would not see him. "I think he knew he would not come back," Helen recalls. "I guess I had a premonition that I would never see him again." All too sadly, her premonition later proved correct.

A few days after Helen left, Maurice himself boarded a bus which would take him to Ft. Meade. His last letter from the United States was dated June 29, 1944 (one day before his twentieth birthday), and at that time, he had just visited Boston, Massachusetts. He did not seem to like Boston and complained that it was a "dirty city."

Shortly afterward, Maurice left the United States, probably in early July of 1944, departing on a large ship and arriving somewhere in Great Britain a few days later. No one knows when he actually arrived in Europe, but he received additional training in England for a brief period of time before he was shipped across the English Channel to the northern seacoast of France, where American troops had already begun to invade.

In Maurice's first letter from France to his wife, dated July 24, 1944, he noted in the upper right corner that he was "somewhere in France." In fact, he was probably in the vicinity of St. Lo at the time. He listed his new address, in care of Co. I of the 116th Infantry Regiment, his new assignment.

By the time Maurice arrived, the 116th had completed its invasion of Omaha Beach, entering Normandy at a small community known as Vierville. Like several areas of the French beachhead, Vierville was heavily guarded by Nazis. Some were stationed in pillboxes--small, concrete fortifications with just enough room for only a couple of soldiers. Inside, while enjoying the relative safety of the pillbox, the Nazis could fire a machine gun from a slit in the pillbox upon the invading Allied troops. Capturing and disarming one pillbox could cost dozens of American lives.

The American troops which survived D-Day had experienced one of the bloodiest battles ever fought in the history of the United States. The 116th Infantry lost nearly half its men. Those who remained continued to battle in the vicinity of Vierville from June 6 until June 9, 1944.

The 116th Infantry had a long, proud history. Beginning with the French and Indian War (1755-1763), its troops had served in every American military engagement except the Spanish-American War. During the Civil War, the 116th had once been commanded by Confederate General Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, so it was nicknamed, "the Stonewallers." Most of the 116th Infantry troops came from Virginia, for it was a national guard unit which had been activated on February 3, 1941, before the United States entered the war. In mid-February, the infantry was sent to Ft. Meade, Maryland, to train for combat, apparently in anticipation of war. The soldiers of Co. I, to which Maurice was assigned, were primarily from Winchester, Virginia.

The soldiers of the 116th were no strangers to tragedy. Months before Maurice joined them, the 29th Division set sail from New York City, bound for Scotland, in two British ships. HMS Queen Mary left the harbor on September 27, 1943, and HMS Queen Elizabeth set sail on October 5. Calamity first struck on October 2, when the Queen Mary knifed into HMS Curacao, as the Curacao attempted to pass in front. The passengers of the Queen Mary barely felt the wreck, but 332 British sailors lost their lives when the Curacao sank to the bottom of the sea.

Unfortunately, the 116th had lost so many men on the beachhead on D-Day that it was hardly recognizable. Dozens of families in Virginia mourned the loss of a son.

At this point, it is important for the reader to understand the chain-of-command of Maurice's new Army unit, because the references in the various historic accounts which follow will make little sense without bearing the organizational structure in mind. Maurice's Company I, commanded by Captain Mifflin B. Clowe, Jr., was one of about twenty companies in the 116th Infantry Regiment. Companies I, K, L, M, and HQ formed the 3rd Battalion of the regiment, commanded by Major William Puntenney. The 116th Infantry served alongside the 115th Infantry and the 175th Infantry, which were collectively called the 29th Infantry Division, commanded by Major General Charles H. Gerhardt. The division was sometimes called, "The 29'ers." On D-Day, the 29th Division was part of the 5th Army Corps, which, in turn, was part of the U.S. 1st Army, commanded by General Bradley, but the division was later transferred among other corps and armies throughout the France-Germany campaign.

After D-Day, and before Maurice's arrival, the 116th Infantry pushed southward into France. The list of engagements before Maurice's arrival is as follows: From June 6 through June 9, the regiment entered France at Omaha beach and fought in the area of Vierville; from June 9 through 12 the 116th fought in the vicinity of La Cambe. From June 12 through July 12, the infantry fought at Couvains. From July 12 through July 19, the regiment engaged in a battle 1,500 yards east of the French community of Martinville.

When Maurice arrived in late July, the 116th Infantry had pushed only about twenty miles south of the French beachhead at Vierville but had captured the city of St. Lo. The Battle of St. Lo, which lasted from July 9 until July 20, was a famous battle which General Eisenhower later hailed as the event which opened much of the French territory to invading American troops. Major Thomas D. Howie, the commander of the 3rd Battalion, was killed at St. Lo and later acclaimed for heroism during this battle; he was replaced by Major William Puntenney.

Maurice probably arrived in France on Omaha Beach about July 24, and then traveled by truck several miles south to the vicinity of St. Lo, from which location the Allied Invasion would continue to press in a westerly direction, since much of the French territory west of St. Lo was still occupied by Nazi troops. Being a replacement soldier, Maurice knew none of the other men in the 116th Infantry, so he had to make new friends and adjust to incredibly different circumstances. No doubt, the loneliness he experienced affected his performance as a soldier, but after five weeks of participation, he would have no doubt adjusted.

From his arrival about July 24 until his death in late August of 1944, Maurice participated in the 116th Infantry's activities in Northern France, which are described by military historian John W. Schildt as follows:

The 29th and 116th Infantry had been on the line for forty-five days. The twenty miles from the beaches of Omaha Beach to St. Lo had been extremely costly. The 29th Division had lost approximately 7,000 men, with almost half of them being from the 116th. The regiment bore little resemblance to the unit that hit the beach [on D-Day]. Many were resting beneath the skies of France in the military cemetery at La Cambe. Others were in nearby hospitals, or had been shipped back to England or the states. After the fall of St. Lo, the 29th was placed in reserve for rest and refitting. The Second Battalion bivouacked among the orchards of St. Clairsurl Elle. The battalion had captured the village a month earlier.

It was great to have hot meals, hot showers, and clean uniforms. And for awhile the troops were away from the immediate threat of death and destruction.

The weather even cooperated the next few days. The six weeks in France had been a mixture of cold damp days, then sultry heat. But during the break it was ideal.

Films were shown throughout the day in an old barn. They were jerky from constant use, but the movies provided a temporary break from reality.

Red Cross canteen trucks arrived from time to time. American ladies dispersed coffee, doughnuts, and paperback books. . . .

Then came Operation Cobra. For three days there was a massive Allied bombardment of the German lines. This was in preparation for the attack to be made on a four-mile-wide front west of St. Lo. The objective was to break out from the beachhead and drive the enemy back. COBRA was launched on July 28. Over two million men engaged in combat. Then on August 15, came the Allied invasion of Southern France.

The Germans found a delaying action as they fell back toward Vire. Strangely, they had no fixed defenses, but prepared obstacles along the way, including the deadly mines. The 115th and 116th were pursuing the enemy while the 175th was in reserve.

Vire was an old town, no stranger to death and destruction. Vire had been visited by the Black Plague. During the Middle Ages, feudal lords fought over possession of the town. And like many places, Vire suffered during the Hundred Years War. Bombs from D-Day had fallen on Vire, causing numerous casualties. Now the Germans and Americans were fighting over the town.

Battalion fronts were largely two hundred yards wide. But the fifteen mile advance of the 116th from the village of Moyan to Vire involved a heavy cost. In fact, the Second Battalion lost almost fifty percent in a two-week period. The nearer the 29th got to Vire, the heavier the resistance they encountered. The objective of the 115th was to secure the Vire-St. Sever Calvados Road. The 116th was to occupy the high ground north and northwest of Vire.

The old city reminded Major [Charles] Cawthon of St. Lo. He feared taking Vire would be as costly as �the Capital of Ruins.' As always, an artillery barrage was to precede the attack, then it would be up to the foot soldier to seek to destroy his opponents by �fire and maneuver.' Hill 219 loomed in front of the Stonewallers as a major obstacle.

One day, leaflets had been dropped on Vire, warning the residents to flee. However, the leaflets were blown away, and the citizens rushed to the streets to celebrate when the air armada appeared overhead. As a result, many lost their lives, and much of the city was destroyed. From the beginning of COBRA until its capture by the 116th, Vire was pounded by American artillery, and once it fell, the city was pounded by the retreating Germans.

Hills always provide a military barrier. Normally they give the defender a view of the area, and fields of fire against an advance in the valley. Blocking the 116th's approach to Vire were two hills, numbered according to their height above sea level, measured of course in meters.

The trucks of the 116th moved out [of Vire] at sixty-yard intervals. They were occupied by serious looking young men, sitting upright with their rifles between their knees. It reminded Charles Cawthon of being packed in the boats approaching the Normandy shore. He was also appalled and shocked by �how little of the �old' pre-D-Day Battalion remained.' One chaplain said the seven weeks in France reminded him of the verse in Isaiah where it speaks of �sheep going to the slaughter.'

The scenes along the road were not pretty. There was the wreckage of battle, demolished farm buildings, blasted hedgerows, and of course, St. Lo, a pile of rubble. A traffic jam resulted due to the fact that the 2nd Armored Division was also moving up. The Stonewallers sweated for awhile. German artillery was still nearby, and if Jerry opened up, they were sitting ducks.

In two hours, the Second Battalion moved five miles forward, and men slept in the nearby fields. It was a warm night and near midnight the troops were ordered to �move out.' The column plodded on, many men half asleep. About [3:00 a.m.], the assembly area was reached.

In the early morning fog, the 116th advanced through fields and orchards. Two new lieutenants and the scouts of the leading companies of the Second Battalion went down in a burst of machine gun fire. All three battalions fought throughout the day. That night, a lone German plane dropped a white flare on the area, making the Stonewallers think a counterattack was coming.

In the morning, G Company was sent to secure a crossroads on the right flank, a place called La Denisiere. A bloody, small unit action developed, and once again, far from home and loved ones, at an unheard-of place, young men [of the infantry] fell.

Late in the afternoon, Major Cawthon received word that Colonel Bingham had been wounded in the arm and was being evacuated. Cawthon was now the battalion commander. The day was July 30. His first act was to go to the crossroads where G Company had been engaged. A destroyed German half track was in a ditch. And lying around by the edge of the road were the dead and wounded of G Company.

The day was not over. The commander of Company F was killed, along with a new lieutenant in H Company. Already there were heavy losses, and the campaign was just beginning.

During the night, the Germans pulled back, and the next morning the 116th advanced, amazed at the tank tracks. Despite their losses, the Germans always seemed to find more equipment. Wrecked vehicles were along the road as well as the graves of German soldiers.

On the 6th of August, the tanks departed, leaving the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 116th on top of Hill 219. Then came the order to prepare for the attack on Vire. The village resembled a post card scene with its red tile roofs. But like so many places, it was in the path of contending armies. So the objective was Vire and its five roads.

Major Cawthon describes the action:

The two assault companies started in columns abreast down the steep hillside and were immediately lost in view in the underbrush and dark shadows. The battalion command group followed, slipping and sliding, holding on to brush and trees. At the bottom, we passed one of the first wounded, a rifleman bandaged and lying beside the river. He raised himself on an elbow and asked to be helped back to the aid station. I had to tell him that none of our small party could be spared, but that the stretcher bearers with the reserve company were following directly behind and would take care of him. He sank back without complaint; a recurring and troubling wonder is whether he was ever found in the fading light.

We forded the shallow river and started up the opposite slope toward a racket of gunfire beyond the wall of houses. A number of stragglers were drifting back toward the river, each announcing himself to be the sole survivor of his squad or platoon. They were added to our party, and we entered the town through a narrow lane that opened between the houses. The scene inside was worthy of a witches' sabbath; the night lit by the undulating red glow of burning buildings, all overhung by a pall of smoke. The only orgy under way, however, was that of destruction; parties of Germans were trying to surrender; others were trying to withdraw and doing a lot of yelling; tracer bullets crisscrossed and ricocheted off the rubble.

As night fell, the perimeter was secured, and the wounded gathered in the courtyard. The American surgeon was slow to arrive. But a captured German doctor gave emergency care with extreme precision. The German worked with almost an assembly line of effort, stanching, cleaning, and bandaging the wounded.

The Germans still occupied Hills 251 and 203 south and southeast of Vire. The hills dominated the area, and as long as they remained in enemy hands, there was danger. Units of the 2nd Infantry arrived to replace the Stonewallers, and the 116th was given a new assignment. The 1st Battalion was to take Hill 203, while the 2nd was given the task of securing Hill 251. Some of the men felt the brass desired the elimination of the 116th as they were given so many difficult assignments.

The attacks began at [6:00 p.m.] on August 7. The night was spent at the base of the hill, with the main attack to begin in the morning.

Major Cawthon ordered one rifle company, now down to about fifty men, and the heavy weapons company to form a fire base on the right, while the other two companies advanced �along a farm road.'

This time opposition was light. Most of the Germans had pulled out during the night. G Company overran the summit and took several dozen prisoners.

Schildt then describes the importance of these actions in the conquest of Western France:

Sensational events often upstage those of equal importance, such as the capture of Vire. All eyes were focused on the astonishing success of the Third Army. Patton's tanks were sweeping south in the movement that created the Falaise Pocket. Patton had encountered little opposition in Brittany, and what he did, he often bypassed, leaving others to mop up. By August 6, tanks of the 6th Armored were on the outskirts of Brest.

Yet Vire was the city �envisioned by General Eisenhower as the pivotal point on which the American Army would swing to the east, then to the north, and finally to the northwest to encircle the enemy's Normandy Army, the Seventh.' And Vire was now in American hands, due largely to the efforts of �The Long Line of Splendor,' the 116th Infantry.

Thursday, August 10, 1944. Maurice wrote his first letter from Europe to his mother and father. He did not complain of anything and seemed to be content, telling very little of his most recent experiences.

Monday, August 14, 1944. Maurice again wrote his parents. By this time, his letter reflects a bit of worry, for he wrote, "What little I've saw [sic] over here sure makes me appreciate what I had when I was at home. I hardly ever saw any of the boys reading their little Bibles until we got here, but now you can see them. They change and change fast. All it takes is a couple of close shells."

Saturday, August 19, 1944. Maurice was apparently becoming a little homesick, for by that time, he had been in a foxhole, fighting in some of the military engagements. He wrote his wife the following letter:

My Dearest Wife:

Well sweetheart I'll drop you a couple of lines again tonite [sic] while I'm not doing anything. It's kinda [sic] raining a little--hope my hole don't fill up with water. I might accidentally drown. Tomorrow is Sunday again. Wonder what you will be doing. I guess I'll go to church in the morning. Honey, your old man is getting pretty good here lately. All joking aside, honey, when I get back home, I don't want to miss a single Sunday going to church. I know how important it is now. . . .

Sunday, August 20, 1944. Military historian Schildt describes the activities of the 116th Infantry on the date that Maurice wrote his second-last letter to his wife, Helen. The church service mentioned by Maurice in the letter is specifically discussed by Schildt:

Sunday, August 20 was observed as a day of rest, �with appropriate religious exercises.' The Chaplains of the 116th held several services that day. There was a large attendance. Men were glad to be alive. And they wanted to remember those who had walked by their side and had answered �the last roll call.'

Then word began to filter down that the 29th was moving out. As the Allied Armies moved inland, General Eisenhower faced major supply problems. The American Seventh Army had landed in southern France on August 15 and was moving to link up with other elements. Patton's Third Army was also moving rapidly forward. All these troops had to be supplied, and Cherbourg was the only main port. If the troops were properly supplied, the war might just be over by Christmas.

Pockets of German resistance had to be removed from St. Malo, Lorient, St. Nazaire, and Brest. Therefore, an advance was ordered to Brittany. The 2nd and 8th U.S. Divisions were assigned the task of mopping up the area east of the Pennfield River. The mission of the 29th Division was to take Brest.

The city of Brest had a pre-war population of 85,000. In WWI, it became the chief American port in France. During the 1920's and 30's, the French continued to develop Brest. Thus it was France's chief naval port. In 1940, Brest, a real prize, fell into German hands. In the magnificent harbor, the Germans constructed a large submarine base. It was built so well that it withstood continued Allied bombings. The Germans realized the importance of Brest to the Allies. Winter weather would limit activity on the beach and at Cherbourg. Therefore, another major port was imperative. Capture of Brest would give the Allies another first class port and reduce the German submarine menace. The Germans had to defend Brest; the Allies had to take it.

Rumor had the 29th staying at Brest at the completion of the campaign, while the Ninth Army would be the army of occupation once total German surrender occurred. However there were miles and miles to go, and battles to be fought before this happened. Tuesday, August 22, was a great day for the 29th and for the men of the 116th. After two and a half months of bitter fighting, the men received a glorious welcome. In mid-morning the trucks pulled out on the first leg of the 270-mile trip to the Brittany Peninsula. The vehicles rumbled through the narrow, flag-bedecked towns of Brittany.

Brittany had escaped most of the ravages of war. With the exception of her port towns, the villages and countryside were untouched. The land was lush and green, so different from the battlefields of Normandy. There was even a resemblance to Devon and Cornwall, where the 116th had trained in England.

The citizens turned out to greet the 29th. Cheers swept the air. It was almost like 1862 when the Stonewall brigade had delivered Winchester from enemy hands. The residents held up the V for victory sign. When the trucks slowed, the citizens threw apples and bread to the soldiers, and when stops were made, the troops were given eggs and calvados. Some of the French were anxious for the American cigarettes and chocolate. The French flags were everywhere. One town flew a banner, �Welcome Liberators.' And when the 29'ers returned in 1988, they were still called �Liberators.'

Schildt's description of the defenses of the city of Brest are most significant, for they detail the obstacles faced by Maurice during the last few days of his life, as follows:

The defenses of Brest had been constructed to withstand attack by land or sea. For miles beyond the city, the hedgerows had been prepared for the expected offensive. An outer band of propelled guns, dug well into the earth, some fortified with concrete and steel, all of them forming a great defensive arc that swept around the city. An inner band of ramparts was modernized with steel pillboxes, antitank ditches, road barriers, and minefields. With months of preparation, these positions had become the ultimate in defense. Garrisoned by the German 2d Parachute Division and units of the German Navy and Marines, this fortress, according to G-2 estimates, held approximately twenty thousand enemy. This estimate, as it developed in the ensuing campaign, was far too low. Actually, the Brest garrison comprised nearly fifty thousand.

Brest received the personal order of Adolf Hitler to hold out for three months, and to this order Maj. Gen. Hermann Ramcket, fortress commander, had given a vigorously affirmative �Jawohll!' General Ramcket had commanded the Germans' 1st Parachute Division in its long defense of Monte Cassino in Italy, and he apparently was determined that the stand of the Brest garrison be equally epic. �I expect every parachutist to execute his duties with fanatical zeal,' he told his men, insisting that the defense of Brest become �the same glorious page in the history of the 2d Parachute Division that Monte Cassino has been for the 1st. The whole world looks to Brest and its defenders, of which you are the main pillar. Long live Der Fuhrer!' On August 22, Maurice wrote the last letter that Helen would receive from him. It was apparent from this letter that Maurice was missing his young bride. Consistent with his fun-filled prankster personality, he teased her, telling her he had seen "lots of beautiful girls in France," but he told her not to worry because, "My French would have to improve a lot before I could say much."

Wednesday, August 23, 1944. Military historian Schildt continues:

All elements of the division had completed their motor march by early afternoon of August 23, and had closed into an assembly area in the general vicinity of Ploudalmezeau, approximately ten miles northwest of Brest. The 116th CT, earlier arrivals in this area, dispatched [Maurice's] 3d Battalion to a forward assembly area one mile northeast of St. Renan on August 24.

Thursday and Friday, August 24-25. Former Co. K soldier Felix Branham, who now lives in Silver Springs, Indiana, states that Co. I traveled from Vire to the Brest penninsula by truck convoy. He states that Co. I "jumped off" on August 25, which means that the company began its mission, studied maps of the area, and discussed strategies with their company commander. As to the activities of August 24 and 25, military historian Schildt continues, as follows:

From here the [3d] battalion sent patrols forward to the line of departure already selected for the Division's attack. This line, approximately four miles northwest of Brest, faced generally southeast toward that city.

Since few American troops had previously occupied this part of Brittany, the character of the country was doubtful, and although it was known that no sizeable enemy forces remained in this area, an alertness not found in normal �rear areas' was maintained. The regiments outposted their assembly areas and conducted reconnaissance patrols.

The 29th Division formed the right flank of VIII Corps' three-division arc before Brest, with the adjactent 89th Division in position to attack from the north and the 2d Division from the east.

During the night of August 24-25, the 115th and 116th moved up to positions close to the line of departure. At 1:00 p.m. on August 25, the battle began. The fighting for Brest had begun. The 115th and 116th moved forward in a column of battalions for the attack. The 115th was on the left, the advance was to the south.

The 115th met heavy resistance. Enemy fire came from automatic weapons and self-propelled guns. Initially, the 3rd Battalion of the 116th met little resistance, and by 4:00 a.m., the 1st Battalion was ordered to take the high ground near Guilers and Keriolet. This was to be achieved by attacking on the right flank of the 3rd Battalion. Enemy fire increased, and the regiments were ordered to dig in for the night.

Saturday and Sunday, August 26-27, 1944. The 116th Infantry continued battle in the vicinity of Brest. During this time, the infantry marched on foot southward from the direction of St. Renan toward Guilers. According to Felix Branham, as Co. I advanced toward Brest, they gained only about 200 feet per day, primarily fighting from foxholes.

According to the U.S. Army, Maurice was killed on August 27, but the date is not certain. According to Major Puntenney, who was Maurice's battalion commander, on August 27, the 116th Infantry and Co. I, in particular, were located on the road which joins St. Renan with Guilers, about 2,000 yards west of Guilers, a small French town which was heavily defended by the Germans, only a few miles northwest of Brest. It now appears that Guilers is the most likely site of Maurice's death. Initially, the United States Army considered Maurice as "missing in action," which means that the soldiers of his Infantry could not establish exactly what happened to him.

From Guilers, the 116th marched on foot to the community of La Trinite, only about a mile southwest of Guilers, but no soldier lost his life at La Trinite on August 27. No one knows the precise circumstances under which young Maurice O'Connell lost his life, but he apparently failed to answer a roll call on August 27, 1944.

Some of the answers to this mystery can be found in the "After Action Report" filed by the 3rd Battalion, which states as follows:

Throughout the day of 23 August 1944, no time was lost to prepare our troops for the ensuing operations. All the battalions were sent through a training program in which the use of assault equipment, i.e. pole charges, bangalore torpedoes, flame throwers, etc., was practiced.

Orders were received from the Commanding General, 29th Infantry Division, for the 3rd Battalion to move into an assembly area, and at [6:30 p.m.] 24 August 1944, Company I was dispatched with the mission to move to the Line of Departure and outpost it. Forthwith, a patrol was sent out from Company I and enemy resistance was met in the vicinity of St. Georges de Rouelle (702052). Due chiefly to inclement weather and poor visibility, this enemy pocket was not cleared out until the following day, 25 August 1944.

Orders were received from the Commanding General, 29th Infantry Division, for this Regiment to jump off on the attack at [1:00 p.m.] 24 August 1944, but were later rescinded and notice given to be prepared to take the offensive at [1:00 p.m.] 25 August 1944. The 24-hour deferment gave the units valuable time in which to continue their training in the use of assault equipment, which would be of great value in the approaching operations, the battle for the city of Brest (960000) and adjoining terrain.

The attack jumped off at [1:00 p.m.] 25 August 1944, with the 3rd Battalion in the lead and followed by the 1st Battalion, echeloned to the right rear. The objective was Guilers (903039), or Objective A. A great deal of enemy resistance was encountered, but [Guilers] was taken by [8:45 p.m.] 25 August 1944. Following the seizure of the objective, the 3rd Battalion was directed to button up, reorganize and make ready to set out on the attack again the following morning. These plans were stymied somewhat, when at [10:00 p.m.] 25 August 1944, the 3rd Battalion was subjected to severe pounding by enemy artillery and AA guns. The barrage inflicted numerous casualties in the 3rd Battalion's personnel.

At [6:15 p.m.] 25 August 1944, the 1st Battalion, 116th Infantry was ordered to bypass the 3rd Battalion and set out for Objective B. This push by the 1st Battalion was met by powerful enemy resistance from a point commanding the high ground of the objective. Following reorganization, the 1st Battalion again sought to penetrate the outer defenses of the objective, meeting with little success.

At [6:00 p.m.] 26 August 1944, A Company was partially successful in obtaining a portion of the high ground of Objective B. C Company swung around the left flank in an effort to occupy the objective, only to run flush into a counterattack. The enemy counter-thrust was driven off in short order. However, enemy fire was still very much in evidence. The enemy placed a heavy concentration of overhead fire on the 1st Battaion and A Company withdrew to permit our artillery to place a barrage on the concrete embrasure from which the strong enemy fire was emanating. Our 105 mm howitzer [cannon] shelled the enemy strongpoint, but with little or no effect. It was then decided to have our heavier artillery concentrate on the enemy position, and the 155's and 8" howitzers were used with some success.

Immediately following the barrage by our guns, the 1st Battalion jumped off on a resumption of the attack, but it was found that the enemy, despite our heavy artillery barrage, continued to occupy the pillbox. At this time, [7:30 p.m.] 26 August 1944, our Battalions closed up for the night, only to set out again on the offensive at [8:00 a.m.] 27 August 1944. Upon moving out the following morning at 8:00, the 3rd Battalion advanced somewhat slowly, with the 1st battalion still attempting to take the concrete embrasure.

Heavy fighting was in progress throughout the day. It was then decided to have an air mission placed on the enemy pillbox. Four P-47's flew over to take up the mission. Our [3rd] Battalion's displayed their air recognition panels, and upon recognition, our planes power-dived on the enemy position, dropping bombs and strafing on the way down. The air mission was successful in that two of the bombs plastered the target. The other bombs that were dropped either went over the target or fell short of it. Further, two of the bombs failed to explode.

Following a telephone conversation with the Commanding General, 29th Infantry Division, orders were given for the 116th Infantry Regiment to be relieved on position, still in contact with the enemy, and to withdraw from these positions, after being relieved by elements of the 115th Infantry, 29th Infantry Division. Immediately upon the receipt of these orders, the 116th Infantry set out to take up its new positions. The 2nd Battalion was ordered to move to the new assembly area [near La Conquet, via La Trinite], a distance of approximately 12 miles.

The movement, accomplished in speedy fashion, saw the troops setting out for strange territory with no knowledge as to the presence of friendly or enemy troops. The switch to the new territory was done in splendid fashion, and it was carried out with no incidents. The 2nd Battalion led the way, followed by the 3rd Battalion and 1st Battalion, in that order.

The last battalion to be relieved on the line was the 1st battalion, which was relieved at [5:56 p.m.] 28 August 1944, and immediately set out for the new assembly area. It was closed in at approximately [11:15 a.m.] 28 August 1944. At [noon] 28 August 1944, the 2nd Battalion was directed to seize and secure Objective Z. Enemy resistance was encountered chiefly from heavy mortar and small arms, but the Battalion pushed ahead and reached the western portion of Objective Z. It was then ordered to button up for the night.

* * * The entire move was completed without incident and no evidence of enemy appeared along the route.

Immediately after moving into its assembly area [near St. Renan], the Regiment was issued maps of the area, including a defense overprint (1:25,000, Sheets 7/10 SE, and 7/8 NE) of the Brest area and a Brest city plan. The information was checked against civilian and FFI information.

The first evidence of enemy resistance was shelling in St. Renan. The enemy endeavored to locate positions of the units facing him by reconaissance patrols of from 10 to 30 men, reconnoitering to Milizac (900087) and 300 yards north of St. Renan (856053).

When the 3rd Battalion, 116th Infantry attacked at [1:00 p.m.] 25 August 1944, the first resistance was developed along the railroad north of Guilers (899044) and several prisoners were taken.

The enemy had a fortified position at CR 89 (900025), surrounded by an AT ditch. In the first days fighting, a slight penetration by a few of our troops was forced by the enemy counterattacked with an estimated three platoons. Artillery and aerial bombardment failed to dislodge the enemy.

By the time the Regiment had moved to the vicinity of Loc Maria Plouzane (834989), the enemy was using a great deal of mortar, artillery and SP fire was encountered.

At the end of the period, this unit was still engaged along the ridge just west of La Trinite (877980). The enemy, stubbornly opposing, consists of 10th and 12th Company, 2nd Para. Regt., periodically strengthened by Marine and Naval personnel, which are absorbed into the command of the 2nd Para. Regt.

Military historian Schildt also writes of the activities on August 26 and 27, as follows:

During the next two days [August 26-27], German resistance increased even more. The 115th relieved the 116th so the Stonewallers could swing around to the flank and exploit a natural ridgeline leading to Brest.

Heavy German fire kept elements of the 115th and 175th pinned down for several days. The enemy was reinforced by paratroopers. Then flanking movements, plus an intense mortar bombardment by [an American] company of the 86th Chemical Battalion cleared the hill. The 29th now held the hill along with a great view of Brest. Divisional artillery could now fire with precision on the German positions. The position was taken on September 3. Three more weeks were to pass before Brest fell [on September 8].

On September 6, German positions were heavily bombed. There was a withdrawal of enemy positions all along the line. The 8th Division and the 115th were able to move forward. The Blue and Gray was now able to look down upon the fortifications of Kergonant.

Maurice was found by the American Graves Registration Service on September 10, 1944. The official burial report noted that he was buried at 10:00 a.m. on September 21, 1944, nearly one month after his death. The body was loaded on a truck along with the bodies of his fallen comrades, and he was buried in his olive drab, combat uniform, without a casket of any type, in Plot M, Row 8, Grave 195, in the United States Military Cemetery at St. James, France, a temporary graveyard for 4,367 soldiers. A wooden cross was erected to mark the site. For identification purposes, one of his dog tags was buried with the body, while the other was placed on the cross itself for future identification. The soldiers buried at St. James were not placed in coffins, but, instead, wrapped in mattress bags or raincoats.

Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, August 28-30, 1944. Historian Schildt continues to describe the action in far western France, as follows:

The 116th had assumed position on the right flank of the 29th on August 28. At noon the 116th in a column of battalions, 2, 3, 1 moved foward and by evening was near Kerguestoc. The next day there was another advance of 500 yards. [August 30] brought little gain. A stalemate developed.

Having returned from Montgomery to Breckinridge County, Helen lived with her mother in McQuady. She began to suspect something was wrong near the beginning of September, when she stopped receiving mail from Maurice. "I loved Alf and Marie," Helen recalls, "so I rode a horse to their house to stay with them for a few days hoping they might hear from Maurice."

On Monday, September 11, a revival began at New Clover Creek Baptist Church, and Bro. Ezra Meador, Director of Missions for the Breckinridge Baptist Association, served as the evangelist. Helen and Marie attended, often wondering whether Maurice was all right. As time passed, Helen became more worried. Sometimes Alf and Marie heard Helen praying for Maurice's safety during her sleep, and they would quietly kneel beside her bed and pray with her. They did not realize that the nightmare was only beginning.

On Monday, September 18, Helen was still visiting her in-laws. While Alf and Marie were at the barn behind their house the telephone rang. Helen answered. "Is Mrs. Helen O'Connell there?" the voiced asked. "I am she," Helen replied. "We have received word from the War Department that your husband is missing in action," the voice announced. The words cut deep like a knife in Helen's heart. She immediately felt numb inside. With little more said, she hung up the telephone and screamed out the back door at Alf and Marie, telling them to come to the house. Realizing that something was terribly wrong, Maurice's parents ran quickly to the back door. When she learned her son was missing in action, Marie screamed in anguish, fearing the worst.

At 10:18 a.m. on September 18, 1944, the Owensboro Branch of Western Union Telegraph received the news that Maurice was missing in action. The telegram from the Secretary of War stated as follows:

THE SECRETARY OF WAR DESIRES ME TO EXPRESS HIS DEEP REGRET THAT YOUR SON PRIVATE FIRST CLASS MAURICE F OCONNELL HAS BEEN REPORTED MISSING IN ACTION SINCE TWENTY SEVEN AUGUST IN FRANCE IF FURTHER DETAILS OR OTHER INFORMATION ARE RECEIVED YOU WILL BE PROMPTLY NOTIFIED

J A ULIO THE ADJUTANT GENERAL

Fourteen-year-old Keenan and Helen laid on a bed and cried. Several family members came by the O'Connell home to comfort them. The anguish seemed worse because no one knew what to think of the message, "missing in action." Young Keenan, distressed at the news, paced the floor and said, "I know he's coming back. I know he's coming back."

Hardinsburg Town Marshal Carl Meador drove to the O'Connell farm and delivered the telegram. While Alfred, Marie, Keenan, and Maurice's wife Helen were all seated at the table eating lunch, they heard the knock at the back door. Meador entered and announced, "Mrs. O'Connell, your son is missing in action," as he handed her the telegram which no mother ever wanted to receive.

Needless to say, the O'Connell family was distraught for several days, especially since no one knew whether Maurice was merely missing in action or dead. Marie's sister, Helen Ryan, stayed at the O'Connell house for awhile, hoping to help calm down the grief-stricken mother.

Finally, on October 10, 1944, the family received a telegram from the War Department which confirmed that Maurice had been killed in action. The telegram stated that he had been killed on September 10.

Still, no other information was provided.

The entire Clover Creek Community was paralyzed with grief. Although the news was met with extreme sadness, at least the family had received the answer. There was no hope that Maurice might still be alive.

On October 17, 1944, the Adjutant General's Office reported Maurice's death, estimating the date as September 10, 1944. A notation on the report stated, "The individual named in this report of death is held by the War Department to have been in a missing in action status from 10 Sept 44 until such absence was terminated on 10 Oct 1944, when evidence considered sufficient to establish the fact of death was received by the Secretary of War from a Commander in the European Area."

On October 26, 1944, apparently after a brief investigation, the U.S. Army officially changed the date of Maurice's death to August 27, 1944. No other details about his death were provided. On November 2, 1944, Brigadier General Robert H. Dunlop wrote Alfred and Marie O'Connell, advising them as follows:

Dear Mr. and Mrs. O'Connell:

Reference is made to the telegram and letter from this office dated 10 and 14 October, respectively, in which you were informed that your son, Private First Class Maurice F. O'Connell, 35700183, was killed in action in France.

A report has now been received that your son was killed in action on 27 August 1944 instead of 10 September 1944. The message contained no other information.

May I again extend my sympathy.

Sincerely yours,

Robert H. Dunlop

Brigadier General, Acting The Adjutant General

Finding little consolation in the letters received from the War Department, Maurice's wife, Helen, wrote the government seeking additional information. On February 17, 1945, Maj. Gen. J. A. Ulio, Adjutant General of the United States, responded to Helen's letter regarding Maurice, stating, in pertinent part, the following:

[I]t is regretted that no reports regarding the attending circumstances have been received in the War Department. I believe, however, you will realize that, to fulfil the vital obligation of conveying casualty information as expeditiously as possible, our commanders in the theaters of operations have been obliged to limit their initial reports to the type, the date, and the place of the casualty, as considerable delay would result if details were procured before these reports were submitted. You may be assured that any additional information that may be received will be forwarded promptly.

While Maurice's family mourned his death, no funeral or memorial service was conducted. His parents wanted to bring his body home and delayed the funeral until then.

Meanwhile, the Allied Forces continued to push into eastern France and, finally, into Germany. The casualties were numerous, to say the least. Finally, the Allies entered Berlin, and eight and a half months after Maurice lost his life, on May 7, 1945, the Germans unconditionally surrendered.

Maurice's grief-stricken wife, Helen, found life difficult to cope with, now that the young husband she had loved so much had passed away. She remained depressed and unhappy, feeling alone and helpless. At her parents' home in McQuady, she spent several days in bed, crying. Once, her father came to her bedside to console his grieving daughter, "Helen, I would give all I ever had and all I will ever have if it would bring him back, but it won't."

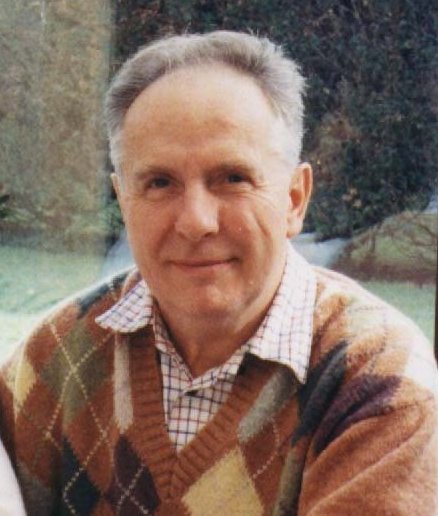

In the Introduction to this biography, I wrote that neither of Maurice's parents was ever told during their lifetimes any of the details of Maurice's death. All they knew was that he was killed in action in France on August 27, 1944. They did not know, for example, how or where he died. In September and October of 1995, I began to search for some answers to the remaining questions. On November 11, 1995, Maurice's widow, Helen Murrell, and I traveled to Staunton, Virginia, for the annual reunion of the 116th Infantry. There, we became acquainted with a member of Co. I and spoke with Captain Jim Kilbourne, the assistant historian of the 116th Infantry.

With the assistance of Congressman Ron Lewis' office, on November 28, 1995, I received a 48-page packet from the U.S. Army which provided more clues. Although some of the answers may never be known, here are at least some probable explanations.

It appears that the most likely location of Maurice's death was the community of Guilers, about three miles southeast of St. Renan. According to Major Puntenney, commanding officer of Maurice's 3rd Battalion, Company I was situated about 2,000 yards northwest of the community of Guilers on August 27. Before the Americans took the town, however, they received orders to march toward La Conquet, on the far western seacoast of France. Major Puntenney points out, however, that the battalion marched to La Trinite, about a mile southwest of Guilers, and that they encountered enemy fire at both locations. Records of the 116th Infantry reveal that no soldier died at La Trinite until after August 27. No one knows under what circumstances that young Maurice O'Connell lost his life, but he was reported missing in action on August 27, 1944. Major Puntenney states that the battalion was able to get medical care to wounded soldiers relatively quickly and that he was not aware of situations where wounded soldiers were abandoned. However, he points out that little attention could be afforded to soldiers who were killed.

Another mystery was the cause of death. A mortar shell head wound seems the most likely answer. Although the embalmer noticed at the time Maurice's body was exhumed that there was a skull fracture, it would presume too much to believe that this was the cause of death. A fracture is simply a break in a bone, and such a break could possibly have been sustained after death. In the opinion of former Co. K member Felix Branham, Maurice was most likely killed either by the bullet from a sniper's rifle or by a mortar shell, since those two types of weapons were the most used by the Nazis on August 27 in the vicinity of Guilers. Branham states that, often, when a soldier was killed in action in the vicinity of Brest, the body would be taken to an area and left there to be identified later.

Col. William E. Ryan, U.S.Army Ret., agrees that, as the company advanced forward, the bodies of servicemen were left at the site, to be located and identified later. While this might seem offensive, in the heat of battle, soldiers are more worried about their own survival than they are about identifying the dead. Col. Ryan states that the St. James Cemetery was a temporary burial ground. Soldiers buried there were not placed in coffins; many were wrapped in canvass or in mattress covers. Once the soldier's family was notified of the death, the family had the option of either leaving the body in France (in which case it would have been left at St. James) or the family could request that the body be returned to the family (in which case it would have been removed from the French cemetery, placed in a casket, and then returned to the United States for burial).

These pieces of information somewhat explain the confusion regarding the communications sent to the O'Connell family. The Army knew on August 27, 1944, that Maurice was "missing in action," and so notified the O'Connells on September 18. Members of Maurice's own infantry did not really know what had happened to him. The Army Graves Registrations Service found Maurice's body on September 10 and notified the Army by October 14, 1944 (the date of the second telegram to the O'Connells) that they had found it. Thus, on October 14, the War Department notified the O'Connells that Maurice had been killed in action, but by standard procedure presumed the death date as September 10. Finally, by November 2, 1944, the date of the final letter from the War Department, the Army had determined, probably after realizing that Maurice had been missing in action since August 27, that he actually died on or about August 27, not on September 10, as had been previously reported.

On April 24, 1945, the Army notified Maurice's parents that it was in possession of a number of personal items that belonged to him. According to an inventory, Maurice's body was found with the following items: one billfold; one U.S. coin; eleven British coins; one French coin; one civilian driver's permit; one identification card; one rusty fountain pen; twenty-one photographs; one photo holder; one shoulder patch bearing the 29th Division emblem; one Social Security card; and one receipt. These items were shipped to his widow, Helen, on June 7, 1945, along with a check in the amount of $7.26 which represented additional money belonging to Maurice. When the O'Connells received Maurice's belongings, this seemed to confirm that the Army had positively identified Maurice's body.

Some people find it difficult to believe that a total of three years and eleven months passed after Maurice died before the United States Government arranged to have his body disinterred from the French gravesite at St. James and then return to Hardinsburg.

On October 4, 1946, the Quartermaster General notified the O'Connells that the War Department had been authorized to return Maurice's body to Hardinsburg, should the family desire to do so. Exactly three years after Maurice's death, on August 27, 1947, the Quartermaster General sent the O'Connells some forms, so they could indicate their desire as to where the body should be buried permanently. On September 22, 1947, Alfred O'Connell signed the forms, indicating that the family wished to bury the body in the Ivy Hill Cemetery in Hardinsburg. Alfred and Marie O'Connell prepared for the funeral, which was but yet another heartbreaking experience.

On May 18, 1948, the Army disinterred the body from the St. James Cemetery. Thomas E. Jones, the embalmer, noted that the dog tags remained on the marker and on the remains, and noted that the body was still buried in the Olive Drab (Combat) Uniform and that the condition of the body was "Skeletal Adv. Decomp-Fract. Skull."

Officials placed the remains in a metal transfer case on May 21, 1948. Then on June 1, 1948, H. F. Pergande, an embalmer, placed the remains in a hermetically-sealed, bronze-colored casket. The casket, in turn, was boxed by H. B. Ryer, Jr.

The transfer from France to Hardinsburg was as follows. On May 23, 1948, the casket was taken by a truck from the French cemetery to Casketing Point A in Cherbourg, a seaport in northern France. From there, it was transported by truck to the Cherbourg Port Unit. On June 17, 1948, it was placed aboard a ship, the USAT Greenville Victory, and transported from Cherbourg, across the Atlantic Ocean, to the port of New York City, where it arrived eight days later on June 25, 1948. At New York City, on June 27, 1948, the casket was placed on a train and taken to DC7 (Distribution Center Columbus), where it arrived on June 28, 1948. In Columbus, officials touched up the paint on the casket, which apparently had been damaged on the ship during the Atlantic voyage.

At 12:42 a.m. on July 8, 1948, a military escort, commanded by Staff Sgt. Harold Menderbull, accompanied the casket on a train from Columbus to Cloverport, where it arrived at the L & N depot at 9:37 a.m. Kenneth F. Bickett of the R. T. Dowell Funeral Home greeted the military escort and the casket with a hearse. From Cloverport, the party drove to the O'Connell house, only a short distance west of the rock quarry.

Maurice was finally home again.

His body lay in state for the next three days. Numerous family and friends came to the house to visit.

Over three years had passed since the Germans had surrendered, and nearly three years had passed since the Japanese had surrendered.

Although military officials argued with her, Marie O'Connell was determined to bring Maurice back home to the family's house, near the rock quarry. The military officials would not permit the casket to be taken to the O'Connell residence without a full military escort, which remained on duty the entire time.

Because of the small size of the sanctuary at New Clover Creek Baptist Church, and because of the large size of the anticipated crowd, Alfred and Marie decided to hold the funeral service at the Hardinsburg Baptist Church.

Eleven days after Maurice's twenty-fourth birthday, on July 11, 1948, the body was taken from the O'Connell home to the Hardinsburg Baptist Church. New Clover Creek's pastor, Bro. William Varble, provided the eulogy and was assisted by Bro. T. E. Smith, pastor of Hardinsburg Baptist Church. The pall bearers included several World War II soldiers who were friends of Maurice, Walter "Junior" Brickey, James O. Gibson, Ted Mattingly, John E. Frank, Ivan E. Furrow, and James O. Burden. Maurice's wife, Helen, attended the funeral alongside her husband, Charles Murrell. There were twenty-three floral tributes, mostly from family and friends. One came from the members at New Clover Creek. After the casket was placed in the front of the church, the following was the order of service:

Hymn, "Safe in the Arms of Jesus"

The Reading of Maurice's Obituary by Miss Nellie Stinnett

Hymn, "Does Jesus Care?"

Prayer by Bro. T. E. Smith

Hymn, "Will the Circle Be Unbroken?"

Scripture and Sermon by Bro. William Varble, who read from Psalms 23,

John 14, and I Corinthians 15

Hymn, "O Think of the Home Over There"

Nellie Stinnett also read a poem which apparently had been very meaningful to Maurice's mother.

After the funeral, the casket was again placed in the hearse, where a short procession continued to Hardinsburg's Ivy Hill Cemetery. At a graveside service, amid a twenty-one gun salute and the recitation of "Taps," the body of young infantryman PFC Maurice Francis O'Connell was finally laid to rest, while the Stars and Stripes were presented to both his mother and his widow.

Alfred O'Connell continued to farm at home. In the late 1970's, he joined the Hardinsburg Baptist Church, where he was baptized. He died March 18, 1987, and was buried in the Ivy Hill Cemetery, to the left of his son Maurice.

Marie O'Connell continued to serve as church clerk at New Clover Creek until July 8, 1955, when she resigned and moved her membership to Hardinsburg Baptist Church. She began working as the supervising cook of the Breckinridge County High School, a position which she held until she retired in 1973 at the age of 70. Family members state that Marie became imbittered by the loss of her first-born child, and that, understandably, she seemed to have much difficulty in coping with the tragedy for the rest of her life. She died March 17, 1982, and was also buried in the Ivy Hill Cemetery, to the right of Maurice.