Khe Sanh Veterans Association Inc.

Red Clay

Newsletter of the Veterans

who served at Khe Sanh Combat Base,

Hill 950, Hill 881, Hill 861, Hill 861-A, Hill 558

Lang-Vei and Surrounding Area

Issue 52 Spring 2002

Special Feature

![]()

Home

In This Issue

Notes From The Editor and Board Incoming

Short Rounds

Memoirs In Memoriam

A Sprinkling Of Your Poetry

![]()

Khe Sanh and The Mongol Prince

By Chaplain Ray William Stubbe

The battle of the Siege of Khe Sanh of early 1968 was far more ominous, dangerous, and significant than had been previously thought. It is miraculous, in fact, that any made it out alive from that battlefield. The key to survival and success in that battle may be attributed to the professionalism, dedication, creativity, and humanity of individuals who were there, most of whom remain to this day, shrouded in obscurity in what has been written of that battle. There were many. One of these is Mirza Munir Baig, known as "Harry." This essay contributes much new information concerning the remarkable Harry, as well as newly acquired information derived from official Hanoi military history books, declassification of highly classified documents from the National Security Agency, memoirs of Khe Sanh participants, new descriptions of intelligence gathering and processing during the Siege, recollections from CIA debriefs of Harry, documents pertaining to use of electronic sensors at Khe Sanh, and numerous other, miscellaneous information.

*****

A Desperate Place:

How Did We Ever Make It Out Alive?

The battlefield of Khe Sanh, occupied 25% of all Vietnam film reports on TV evening shows during February-March, 1968. Shocking images of horror appeared in numerous popular print media, e.g., "The Agony of Khe Sanh" cover of Newsweek, March 18, 1968; its photo essay portrayed desperate young men carrying the bloodied corpse of their Platoon Commander (Don Jacques), and shocked faces and crumpled bodies in deeply-dug trenches. Haunting faces and desperate conditions captured by David Douglas Duncan and the legendary "thousand-yard stare" on the faces of those at Khe Sanh appearing in newspapers reflected the desperate reality that was Khe Sanh.

Possible reenactment of a Dien Bien Phu scenario became an idee fixe for many who feared Khe Sanh's isolation and tenuous defensibility. Overland re-supply via road (QL-9) had become impossible because 9 of the 26 bridges between Ca Lu and Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB) were impassible or destroyed. The KSCB airstrip was closed to air-landed re-supply 12-25 February due to untenably hazardous conditions. The Drop Zone was extremely small and unprotected. Lingering morning fogs precluded aerial reconnaissance and re-supply. Surrounding Khe Sanh, like clutching, choking fingers on a throat, were tens of thousands of encircling enemy troops plus tanks, marking the first use of tanks by the PAVN in the war. President Johnson demanded the Joint Chiefs of Staff declare in writing that Khe Sanh would be held. American defenders received up to 1600 incoming rounds a day -- mostly devastating rockets and artillery on a base 0.9 mi. long and 0.4 mi. wide occupied by approximately 2725 men. Nuclear weapons were being considered for Khe Sanh.

The considerable enemy presence was alarming. Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) intercepts and analysis reported through TOP SECRET TRINE Daily Tactical SIGINT Summaries disclosed a massive movement of enemy infantry units from North Vietnam positioned in Laos just west of Khe Sanh. Formation of a Khe Sanh Front Headquarters to coordinate units of the 304 and 325C Divisions and support units, located directly west of the DMZ, designated B5-T8, had been established 6 December 1967, commanded by Major General Tran Quy Hai, Assistant Chief of Staff, PAVN General Staff, and Political Commissar Comrade Le Quang Dao, Deputy Director of the General Political Directorate for the PAVN.

The considerable PAVN commitment to the Khe Sanh battle, in addition to the formation of a Fron~ Headquarters and investment in the area of two divisions of infantry (one of which, the 304th, had participated in the Dien Bien Phu battle), is reflected ir~ the PAVN Secret [Mat] classified history of the Ho Chi Mirth Trail which reports the total of supplies delivered to B5-TS: double the amount delivered to Tri-Thien, 2.5 times the amount delivered to Region V, and 24.5 times the amount delivered to Nam Bo (an important region that included Saigon and the Delta). Col. Tran Tho, Deputy Operational Commander, responsible for logistics during the Khe Sanh battle, had his hands full! More tonnage of bombs were dropped in this small battlefield area than in all of the Pacific in 1942 and 1943; in an area of 564 square kilometers, friendly fire delivereli some 99,600 tons of ordnance.

Life for those on the hill outposts of Khe Sanh was even more tenuous and austere due to inability of helicopters (their only means of re-supply and medevac support) to penetrate lingering, shrouding fog (known in the area as Crachin, a French word for "spit.") Hill 950, without water for seven days, held a badly wounded man who nearly died; one man on Hill 881-South did die after three days of shrouding fog precluded his medevac, and some corpses decayed for days in a temporary "body bunker." The Company Commander on Hill 881-South, Captain (later Colonel) William H. Dabney, comments: "Ever watch rats crawling in and out of ponchos holding what's left of [men] hit by a 152[mm. artillery round]? The troops did! They were up there five days. Weather socked in. Ripe. We were told we couldn't bury them. We did anyway. Had to."

When Co E, 2/26 occupied Hill 861-A on 22 January 1968, the defenders were rationed to a C-ration meal and half a canteen cup of water a day. On Hill 861, cases of C-rations were stored in an old bomb crater, atop which a guard sat all night to prevent theft. Cpl. Dennis Mannion, a Forward Observer with KILO Co., 3/26, on Hill 861, recalls, "Imagine! A hill armed to the hilt, facing death and destruction daily, and we still had to supply an armed guard to prevent internal theft!" Tragically, one night, an incoming mortar blew off the arm and a leg of the C-ration guard.

Khe Sanh, a place of scintillating beauty -- almost a Garden of Eden -- shrouded horror and death within its beauty. David Leitch, a correspondent for the London Sunday Times, still haunted by memories of the wonderful young men he came to know at Khe Sanh during the Siege battle, captured the life situation: "It was beyond human endurance. I mean, I've been to very many wars, and I'd never experienced being on that level of incoming and that kind of impotence everyone felt. I thought 'the NVA are coming,' you see. I was quite convinced that Giap was going to come over the wire with two NVA divisions. It was just a question of 'when.' It was like being in one of those medieval sieges where you knew you actually had to lose because you didn't have water, or whatever it was, and they were going to get you and cut your throat. Meanwhile, you had a day or two to live, and you had to live like a man. It's a very difficult thing to do. Someone, a Native American Marine, said to me, 'It's a beautiful day to die."'

The famous photographer, David Douglas Duncan, a Marine officer who served in World War II and photographed Korea, passionately protested what he beheld at Khe Sanh, what the defenders there were forced to endure. He added to the title on the cover of his collection of photographs "I Protest!" the words, "In behalf of the men who will never get out, for whom help came too late."

The severity of life at Khe Sanh is reflected in the hell it became for everyone who was there. Clothes rotted off the bodies of those at Khe Sanh who could not take showers for three months. C-rations were frequently limited to one per day. Water was frequently restricted to one canteen cup per day, and there were many days when there was no water. Col. Lownds reflected before a U.S. Senate Committee:

"The battlefield is a dirty and ugly place. All the sophisticated instruments of destruction we can devise won't change it, nor will they change the supreme demands of courage, sacrifice, professional skill and dedication which Marines of each and every generation have met on the field of battle."

Soldiers of the North Vietnamese Army units fared even worse. One soldier, Hoai Phong of 9th Regt., 304 Div, wrote in his diary: "Here, the war is fiercer than in all other places. It is even fiercer than in Co Roong and Dien Bien Phu. All of us stay in underground trenches except the units that engage in combat. We are in the sixtieth day, and B-52s continue to pour bombs onto this area. If visitors come here, they will say that this is an area where it rains bombs. Vegetation and animals, even those who live in deep caves or underground, have been destroyed. One sees nothing but the red dirt."

The intensity of the battle at Khe Sanh is reflected in 11,114 incoming artillery, mortar, and rocket rounds between 18 January-1 April 1968, an average of 150 per day (which was the average for all of I Corps in 1967). U. S. forces fired 117,643 rounds of artillery (including 12,441 rounds of 175mm) and flew 2,602 sorties of B-52s delivering 75,631 tons of ordnance (an average of 35 sorties and 1,022 tons a day, 85% more sorties and 82% more ordnance than the daily average for all of South Vietnam and the DMZ for the prior 12 months). 533 sorties were delivered within 3 kilometers of friendly ground forces at KSCB. In addition, 15,217 sorties were flown by tactical air, a daily average of 184.

Officially, 205 Americans died at Khe Sanh during the battle (20 Jan-31 Mar 1968). That this figure is erroneous is manifest even from official counts of Marine battalions at Khe Sanh, which total 274 American KIA. KIA from other units serving at Khe Sanh adds another 70 for a total of 344. This does not include the casualties of Lang Vei, or an unknown number of defenders lost at the Khe Sanh District Headquarters on 21 January and those from the 37th ARVN Ranger Battalion for which no figures are available. For veterans of the battle at Khe Sanh, "Khe Sanh" means the time they were there. Thus, the KIA from Operation PEGASUS (1-14 April) and those from 15-16 April (the date 1/9 left) add 252 more, for a total of 573 Americans lost during the period 20 January-16 April, the period of time the defenders of Khe Sanh were there.

Commander (Doctor) Robert A. Brown, Commanding Officer of 3d Medical Battalion, whose 2d Platoon of Company C served at Khe Sanh as "CMed," records 2,541 patients seen and treated. Of these 2,037 were wounded in action and 490 were non-battle casualties. 2,249 patients were evacuated of which 292 were returned to duty. Losses by the North Vietnamese Army forces are estimated at well over 10,000 killed. Perhaps the same number of the local, indigenous Bru tribesmen (which were prohibited from being evacuated) was also killed, when census before the battle is compared with census of refugees at resettlements.

Perhaps the greatest battle of the Vietnam War in terms of casualties, publicity, degree of commitment, and prolonged agony -- surprisingly by the early 1970s, it was my perceived experience while serving on active duty that military leadership made concerted efforts to de-emphasize Khe Sanh. For example, when the first LHA was launched, news releases announced that LHA-5 would be named USS KHE SANH; the announcement then changed it to USS DA NANG, and when LHA-5 was commissioned 3 May 1980, it was USS PELELIU. Academic discussion of Khe Sanh centered on strategic conundrums ("Who managed to force the other into the battle?" "Who was actually besieged? .... Who won? .... Was Khe Sanh simply a publicity affair by both sides with little reality? ") I personally overheard professional military historians at the Marine Corps Historical Center question whether "there really were all those enemy at Khe Sanh," whether the North Vietnamese really intended to make a major effort there as at Dien Bien Phu. Where was the anticipated "big, human wave assault?"

Attempting to discern motives (or plans and strategy) from what happened betrays a post hoc ergo proper hoc thinking. At Khe Sanh, absence or presence of results had little to do with a lack of PAVN resolve or action. That Captain Frank James Kennedy was able to deliver several thousand pints of whole blood the evening of 21 January despite a quarter-mile visibility and fog; despite navigating by dead reckoning above a thick cloud layer that obscured hazardous terrain features; despite not having the field in sight; despite having to land his CH53 by auto-rotation and guidance by only a hand-held green signal from an Aldis lamp as his only ground reference; despite incoming rockets while landing, does not reflect what the enemy did. It reflects what Americans did! Likewise, Khe Sanh generally reflects victory by determination, resolve, common courage by numerous individuals despite almost overwhelming, countervailing forces. Defenders of Khe Sanh were subsequently awarded the rare Presidential Unit Citation, which is granted to units for extraordinary heroism to the same degree as that which would be required for the award of the Navy Cross to an individual, one award under the Medal of Honor.

During intense shelling, gun crews remained in the open to fire 105mm howitzers, wire men ran out amid the explosions to splice severed land lines to resume vital communications, men commonly dashed to pull an injured man to safety. Dr. Edward Feldman removed a live mortar round embedded in a living man's abdomen. Forklift operators, deafened by sounds of their equipment to warning noises made by rockets or mortars that were being fired, continued to move their pallets. Those on the Drop Zone (where there was no bunker or trench or hole to run for cover) retrieved supplies while those on the airstrip cleared it of shrapnel so planes could land. Officers and NCOs were continually seen moving among their troops to cheer and check. Stretcherbearers moved casualties to waiting helicopters even as mortars exploded near them. Everyone could not help but see craters in which they could stand and still be below ground level. There was no secure place at Khe Sanh. Yet, everyday courage and determination formed the modus vivendi of those at Khe Sanh. Thousands of Bronze Stars ought to have been awarded, but subsequent acknowledgment was mostly not forthcoming for the valiant defenders of Khe Sanh. The many hundreds at Khe Sanh are now mostly forgotten, consigned to mists of oblivion.

Even the Commander, Colonel David E. Lownds, who with his staff targeted and initiated strike requests for 95% of all local B-52 Arc Light strikes and generally conducted the entire course of the battle, is an obscure person to history. During an ordinary day, his intelligence staff generated targets for 100 TPQ-10 missions, 16 Arc Lights, 100 flights of fixed wing aircraft and up to 500 artillery missions. Yet, when books and articles on the Battle of Khe Sanh are consulted, one does not find an extensive biography of Colonel Lownds or his staff or subordinate commanders. Instead, one usually encounters the names of Generals Giap, Westmoreland, and a few others who may have dictated general policy, but who had little to do with detailed day-to-day operations and tactics. Those who did are mostly "little noted, nor long remembered."

Some may have understandably crumbled emotionally or failed to repulse the repeated assaults. Fierce battles were continually won by the young defenders who successfully repulsed determined attacks by large NVA units: the attack on Khe Sanh village and Hill 861, the attack on Hills 861A and 64, and three assaults against the eastern perimeter, one by a regimental-size force. Some of these involved hand-to-hand combat in darkness. Most left hundreds of dead enemy.

Thus, "Khe Sanh" is not tactics and strategy -- it is not even a place to be analyzed or debated. "Khe Sanh" is the people who were there. The wonder of Khe Sanh is not its prior beauty and subsequent horror, not amazement that we all weren't killed there, not the degree of commitment on all levels. The real wonder of Khe Sanh is that so many of such exemplary character were gathered in one place, certainly not as a result of the insight of Generals or their G-1 staff. Reflecting Napoleon's maxim, "In a war it is not men but the man who counts," Colonel Bruce E Meyers, writing the After Action Report of the battle, noted: "The ultimate success in battle will always hinge on the performance of the individual. In the final analysis, Khe Sanh was no exception. The ability of all those who were at Khe Sanh to perform their assignments in spite of the intensive enemy barrages impacting into their restricted base area while at the same time maintaining a high degree of esprit and Úlan, were a major factor in the successful defense of Khe Sanh."

*****

Mirza Munir Baig -"Harry"

A Major Reason We Made It Out Alive!

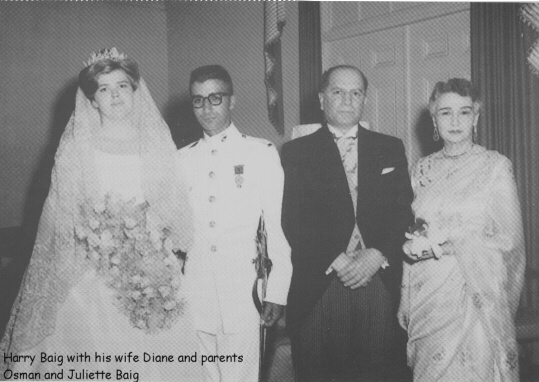

Mirza Munir Baig, "Harry," was born 13 Jan 1932 in Panchgani, India. His name "Munir" means refulgent in classical Arabic, and the name "Baig" is actually a title, not a name, for achievement in the service of the emperor. His mother, Juliette, had been educated at the American University in Beirut, Lebanon (where all her family had been educated from its opening around 1900) and after receiving a scholarship from King Fuad of Egypt, at Clifton College of Cambridge University, where she met her future husband, Osman.

In 1946, Osman was appointed to the British Embassy in Washington, D.C., where the following year Munir and Taimur visited their parents. Among Juliette's new and very good friends were Felix de Weldon, the artist who sculpted the Marine Corps War Memorial (known among Marines as the "Iwo Jima Monument") in Washington, D.C., and his wife, Margot. Juliette took her sons to visit them. "Munir was enchanted with the model," recalls Juliette. It was also in August of 1947 that India and Pakistan became independent of Britain. Osman, being Moslem, became a Pakistani citizen, as did his son Taimur, who recalls: "I was at school when the Partition (India/Pakistan) came through. I went to bed an Indian and literally woke up a Pakistani."

Clifton College prepares boys to enter Sand Hurst, the British school for officer training. Munir was not destined to become a British officer, however. When the time came for him to enroll in Sand Hurst, the turmoil of establishing the new nation of Pakistan resulted in a policy voiding the "father-to-son" tradition of military leadership. By the time the military reasserted its influence in the Pakistan government, it was too late. The British commission their officers at age 19. His father wrote him, "If you want to pursue a military career, the only real military organization left in the world is the United States Marine Corps. Munir was not happy in the world of business. His brother Taimur recalls, "He's always wanted to be a soldier, I guess because of dad." Taimur recalls a time when the family was at Panchgani. He and his brother played "Cowboys and Indians" while his grandmother's friend, Gandhi, sat quietly on the veranda in white robes with legs crossed.

One might reasonably speculate that the effects of war, political turmoil in his homeland, the family saga, life in England, France, Canada, and America -- all conspired to create a sense of "rootlessness" and questions of identity. Who am I? Mongol? Indian? Pakistani? British? American? His brother notes that at times he'd style himself an English country gentleman and dress in jodhpurs and wear a cravat, much to the dismay of his American friends. Munir visited "uncle" Felix de Weldon asking for help to get into the U.S. Marine Corps. Felix took him directly to the Commandant, and he was accepted. Despite all his education and his overwhelmingly prestigious family background, he enlisted 10 Feb 1957 at the Recruiting Station, Washington, D.C., kissed his mother goodbye saying, "Don't fret, mama, I shall make you proud of me," and shipped off to Marine Corps Boot Camp at Parris Island, SC, as a private.

During his first enlistment (10 Feb 56-09 Nov 58), Munir made Sergeant in two years and was awarded a Meritorious Mast for superior performance as a Legal Clerk at Marine Barracks, Brooklyn, NY. Discharged to re-enlist, he re-enlisted on Marine Corps Birthday 1958, and served in the Marine guard detachment aboard the USS INDEPENDENCE. His father, Osman Baig, now Secretary General of the Central Treaty Organization requested Munir be flown off the INDEPENDENCE to be his aide for a week. During this time, he became a naturalized US citizen and was awarded the Coronation Ribbon by the Queen of England (but not permitted to wear it on his Marine Corps uniform) and a Good Conduct Medal.

On 27 May 1960, he was discharged to accept a commission as an officer in the United States Marine Corps. Prior to reporting for training, he married Diane, daughter of Count Nicholas de Rocheford, on 4 June 1960 in St. Matthew's Cathedral, Washington, D.C., surrounded by his Marine buddies. He reported for 26 weeks of training at TBS (The Basic School) where two of his fellow candidates, Gene Hitchcock and Charlie Kappelman (both later served in various intelligence duties in the Marine Corps) first started calling him "Harry" as they hauled him up and down the trails to get him through OCS.

Harry's initial military assignment was artillery. Following training at the Army Artillery and Missile School at Ft. Sill, OK in 1962, he was assigned to 2d 155mm Gun Battery (Self-Propelled) and volunteered for operations off Cuba. Following this experience, he attended Intelligence Research Officer Course, Ft. Holabird, MD and was assigned to 3d CounterIntelligence Team (CIT), 3d Marine Division, where he became Team Leader for ten months and served outside CONUS (12 Sep 63-4 Nov 64). He was awarded the Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal on 11 Feb 1964 for operations with 9th MEB (Marine Expeditionary Brigade) in Vietnam (6 Aug 64-8 Oct 64). During this time, Harry and a jeep driver drove all the way from Chu Lai, through the Hai Van Pass, to the DMZ, with Harry making copious and detailed notes of his observations.

Harry was promoted to Captain (1 April 1965) and participated in Operation HASTINGS (in Vietnam along the DMZ) in July 1966. After completion of AWS, he was assigned to 1st 155 Gun Battery (SP), 3d Marine Division as Executive Officer and as Commanding Officer (5 months). He again departed CONUS 20 April 1967, returning 12 May 1968. During this time, he participated in Operations CUMBERLAND, RUSH, and LIBERTY and subsequently served from 17 September 1967 in G-2, in 3d Marine Division.

During this time, he urged Bob Coolidge to arrange a meeting with the CG, 3d Marine Division, Brigadier General Metzger. Drawing on Marine Corps history, he proposed a mobile guerrilla force composed of NCOs that would live off the land as it roved up and down the Ho Chi Minh Trail destroying re-supply convoys of NVA. Standing aplomb with the large, curved, wide blade of an Indian kukri knife at his side, and stomping his boots like a British officer, he presented the briefing in meticulous detail. After he departed, the General looked to Bob Coolidge and remarked, "Is he for real?"

While serving at Division, his focus was not at all speculative; he was patently practical, and later wrote: "I was the Division G-2 clandestine, intelligence coordinator for military intelligence agencies in the Division TAOR. The 15th Marine Counterintelligence Team and U.S. Army intelligence units had established collection nets far across the Ben Hai River. These nets had penetrated several NVA headquarters and other organizations. One of the tasks of the nets was to report the movements of the 4th Battalion, Van An Rocket Artillery Regiment, and of the Vinh Linh Rocket Battery together with those of their escorting infantry. These units had caused much damage to the Dong Ha and Cua Viet bases earlier during the summer and autumn of 1967. Close surveillance (by a process too complicated to explain herein) and rapid counter fires by artillery and naval gunfire had subsequently prevented them from reaching their firing positions during the late fall and early winter of that year."

The significance of this for Khe Sanh soon became evident. Harry writes: "On the night of 19/20 January 1968, the rocket units moved south once more. Reported and traced along their route by the agents of the 15th Counterintelligence Team, the batteries and their escort were caught and trapped against a bend in the Cua Viet River. Prisoners taken reported that their mission was to rocket the airstrips at Dong Ha and Quang Tri on the early morning of the 21st to prevent helicopters from flying in support of Hills 881S and 861. This part of the enemy's plan failed." On the 23d of January 1968, Harry reported to Khe Sanh as Target Intelligence Officer (TIO), part of a 3d Marine Division G-2 augmentation team that also included Major Jerry Hudson (who had reported earlier to replace Harper Bohr as S-2) and Major Robert E. Coolidge (Special Intelligence Officer). The 26th Marine Regiment staff at the start of the Siege battle was at half strength. Being a unit of 9th MAB, not Ill MAF, half of its staff was on Okinawa. For example, Colonel Lownds never had a Sergeant Major.

The ring Harry wore bore the incused family crest: two crossed swords at the entrance to the Bijapur Fort. His mother recalls, "The position was hereditary in the family, and Munir assumed it was still his but for the British invasion!" Thus, with his great grandfather fighting to keep the fort at Bijapur in mind, Harry was not about to permit besieging forces to overtake this fort! Similarities of the two situations must have been on his mind, for he reportedly spoke to Marines at Khe Sanh about "his" fort in India, how he someday would return and reclaim it! His father, Osman Baig, was a firm believer in being able to talk to spirits of ancestors, and one can only speculate whether Harry may have attended such meditation.

Many recall Harry's arrival, bedecked in unconventional gear. When he first arrived in Vietnam he wore the M-1941 pack and belt harness but was unsatisfied with it. Lt. Bill Smith, an artillery officer of 1/13 who later worked closely with Harry recalls, "The guy had a Boy Scouts back pack and I kept wondering to myself, what am I going to do?" Bob Coolidge explains that Harry bought his pack from Sears, perhaps motivated by his earlier connection with his uncle Selim and his employment there.

Mark Swearengen, the Army Liaison Officer for 175mm batteries at Camp Carroll and the Rockpile, had arrived at Khe Sanh on 18 January. His immediate reaction was one of dismay. He felt a deep concern at what he perceived to be a lack of enthusiasm and recognition for the magnitude of the threat at Khe Sanh. "Then Harry shows up. Captain Steen brought him in. I was at the entrance of the command bunker and thought, 'This guy is different!' He had this British accent and had a kukri knife at his side and spoke as though he were there to single handedly save Khe Sanh. I thought, 'Is this guy crazy?' And then I realized that this is exactly the enthusiasm that we need right now! It didn't take long to realize he was one heck of a team player, not really out to accomplish everything by himself. He'd ask the advice and opinions of others."

He soon became well known for his humor. Harry had a prodigious appetite, and when low on food at Khe Sanh, ate things nobody else sought, such as "sausage patties with grease." "We were getting shelled, rocketed, and one of the radio operators said, 'Captain Baig, I thought Moslems couldn't eat pork,"' recalls Bob Coolidge.

"Well, when we kill the infidel, Allah will give us dispensations," he replied as everyone laughed.

Another radio operator observing the banter remarked, "I don't know what we're laughing about. To Captain Baig we're all infidels!" He frequently referred to someone as, for example, "Wayne Mason, you Christian pig!" or the NVA as "infidels!" Jerry Hudson, S-2 of Regiment, paints a typical scene. "Some of us would tease him from time to time. 'How come you're eating pork and beans?' He'd reply, 'I have to kill some infidels!' Someone would say, 'Give him another can of pork!"'

Mark A. Swearengen, the Army Liaison Officer for 175s in the Khe Sanh command bunker during the Siege, recalls Harry: "If you ever met him and had any discussion with him, you'd never forget him. He was, he could be very enthusiastic about unfortunate situations! He'd talk about being surrounded by thousands of enemy troops, and he'd just bubble with enthusiasm! It would scare the daylights out of most people, but he was enthused about it!" 1Lt. Douglas Meredith, who replaced Capt. Mark Swearengen as the 175 LNO in late February 1968, spoke of Harry as "a superb person, just a tremendously intelligent officer. Anybody would give anything to be with him."

Harry was "bubbly." Navy Lt. (Jg) Bernard D. Cole, the Naval Gunfire Liaison Officer in the regimental bunker recalls, "New ideas, jokes, gibes, prognostications, criticisms/praise of the C-ration meal he had just opened ('Aha! I have biscuits!' the British term for cookies), interplay with others in the bunker, both enlisted and officer -- he seemed always to be in motion physically and active mentally."

Harry was also intolerant of incompetence. The regimental S-2, Jerry Hudson, recalls: "Harry was very, very professional, very intense. Somebody around him who was anything less than that, he'd drive them nuts. He'd jump up and down like an old 'stick-in-the-face,' and yell, 'Incompetence! I cannot stand incompetence!' That's the way he was. He had very, very high standards for himself, and he expected all those that worked with him to be the same." Lt. Cole recalls that Harry "always spoke his mind, no matter what the rank of the person he was addressing. I saw/heard him, more than once, screaming at some senior officer in Saigon (on the phone) when there was a difference of opinion about targeting B-52 strikes." Yet, he never became a victim of anger; he was always in control of himself.

When Harry Baig arrived at Khe Sanh, the Siege battle was two days old. The combat base was a shambles, and the sudden appearance of several tens of thousands of encircling North Vietnamese Army troops who had slipped in from nearby Laos was self-evident in screeches of rockets and whomps of mortars and in the numbed, shock-state reflected in faces with the "thousand-yard stare" and in the "Khe Sanh shuffle" of all there.

Harry had arrived to assist the newly arrived S-2 of 26th Marine Regiment, Jerry Hudson, personally requested by Colonel Lownds upon the normal rotation of the S-2, Capt. Harper L. Bohr, Jr. (who became XO of 3d Recon Bn). When Jerry had graduated from boot camp, the officer he reported to for his first duty was Captain David E. Lownds, recently reactivated from the Marine Corps Reserve.

Originally, Khe Sanh had a mission as a launch site for SOG teams, TIGERHOUND Bird Dog aircraft, CIA-sponsored agents, deep penetration by individuals of the JTAD, and a host of various other activities to collect information, primarily on traffic on the Ho Chi Minh Trail or infiltration into South Vietnam. By now, Khe Sanh had developed into a playground for these units and individuals, all reporting their findings to distant headquarters, while the base itself was in peril and uninformed except for digested, analyzed, and old intelligence from those distant headquarters.

In addition to close-in reconnaissance by patrols from local infantry companies and teams from Company "B," 3d Recon BN, as well as from CAC OSCAR, there were, starting in October 1967, alarming reports from "people-sniffer" helicopters making hundreds of detections close to the base in "uninhabited" jungle! Colonel Lownds had thoroughly familiarized himself with the local terrain by walking it many times alone. There were reports from CIA operatives like the wiry, young Bob Handy, a civilian who suddenly and mysteriously appeared next to Ed Crawford, acting Platoon Commander of G/2/3, as it moved to assault positions during the 1967 Hill Fights at Khe Sanh. There were agent reports from the JTAD at Khe Sanh, the CI Team, the National Police agent net, reports from the Special Forces at Lang Vei, and from the Special Projects team led by George Quamo, who led a large patrol to the Co Roc area in mid-January !968.

Reports from Signals Intelligence, intercepts of NVA radio transmissions and analysis of who reported to whom and how often in order to determine chain of command and location of headquarters, proved especially useful. By I Jan 1968, EC-47 aircraft were consistently flying more than 900 sorties a month. EC-47s of 460th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing that covered Khe Sanh flew unmolested due to their "cover" of similarity to AC-47 SPOOKY gunship, dropping psychological warfare leaflets when available. So significant was the contribution by EC47's ARDF that 90% of all B-52 strikes at Khe Sanh during the siege battle were targeted through ARDF data. Brigadier General George J. Keegan noted, "The Air Force thoroughly reconnoitered I Corps using special sensors plus ARDE"

As the Siege opened, Major George Quamo at the Top Secret FOB-3 camp appended to KSCB, personally ensured a LIMA was strung from the bowels of his deep bunker to the "2" shop of the 26th Marines bunker. Thus, Quamo could ensure that intercepted NVA radio transmissions, translated by a Vietnamese in his bunker, could be shared in "real time." In addition, a plethora of information from a wide variety of sources poured into the "2" shop. These included photo recon missions, including GIANT DRAGON (U-2 aircraft) reports from NPIC. There were RED HAZE reports, SLAR, reports from Bru Montagnards, and the newly developed and seeded electronic sensors, diverted from being seeded in Laos.

Soon information was received as fast as the numbers of encircling NVA soldiers were swelling. Jerry Hudson's arrival was a matter of total immersion. He was thrown into the midst of the tumultuous prelude of the ominous first act now unfolding. "They sent me up there to try to get in the middle [of all these intelligence activities] and direct traffic," recalls Hudson. "At Khe Sanh, there was a whole collection of intelligence agencies gathering information under a lot of authorities, and information was all going back to Saigon and other places, and it wasn't being circulated at Khe Sanh, and we wanted to see if we could get a better handle on the situation."

According to Capt, Jerry Hudson, S-2 of 26th Marines, the abbreviated regimental staff at Khe Sanh was suddenly supported by "...what, at that time, was probably the biggest intelligence operation as part of a regimental operation that I was aware of, and I was pretty much attuned to what was going on. We were mighty close to receiving more information than we could assimilate. It was about that time that Harry Baig and Bob Coolidge arrived, and we began to put some direction and order to this mass of information and tried to keep Colonel Lownds advised so he could make timely decisions and prioritize his decision-making process."

Harry Baig established a section that is not normal to an infantry regiment. Colonel Lownds, in his FMFPAC Debrief, commented that a regiment does not have assets for Target Intelligence, but "General Tompkins automatically started funneling people in to me, and I built a TIO section -- Target Information Section. They were needed. I couldn't have done the job properly with the people I had unless I had this TIO section."

Soon both Jerry Hudson and Harry Baig were feverishly collating and evaluating thousands of bits of information on a daily, and nightly, basis. The Naval Gunfire Liaison Officer who worked with him, Lt.(jg) Bernard D. Cole, recalls that Harry "worked tirelessly, nominally a 12-hour watch, but in reality he was there at least 18 hours a day." Cole, who styled himself "Commander, Naval Forces, Khe Sanh" was, in Harry's description, "the naval gunfire officer, without ships," and "an excellent Assistant TIO."

The Fire Support Coordination Center (FSCC), located adjacent the S-3 shop in the 26th Marines COC (Command Operations Center) bunker, assembled some unusually remarkable men -- few in numbers, but with a creative ability to devise entirely new and effective tactics. In addition to Commanding Officer of 1/13 Lt. Col. John A. Hennelly, Captain Baig and Lt.(jg) Cole of the U.S. Navy, there was: the 24-year-old artilleryman Capt. Kent Steen; Marine aviator, Capt. Richard Donaghy; and U.S. Army Liaison Officer for the 175mm guns, Capt. Mark Swearengen, then 1/Lt. Douglas Meredith. Such a staff, composed of intelligence, infantry, artillery, and air, and from three different military services -while providing a variety of differing perspectives -could easily have fragmented. Yet, Colonel Hennelly's calm, yet firm manner developed them into a harmonious team in which he encouraged free venting of new ideas. Capt. Meredith recalls: "We tried anything. No one ever laughed at a dumb idea. Everything was considered and all were treated with respect. I recall one day asking the aviator why napalm was never dropped at night. It was brainstorming at its best."

Kent Steen recalls this particular discussion and decision: "Napaim, by rule, is only dropped at low level and during daylight. The casings are flimsy and with almost unpredictable aerodynamics. During one of our brainstorms, we determined that the NVA script did not call for napalto to rain on them at night and in the fog and from an altitude. We then set about creating a scheme for doing it. We determined that if we brought the aircraft in at much lower altitudes, say 3500 or 5000 feet, we could get the canisters to hold together and make a reasonably predictable trajectory... The hard part was goading our aviator counterparts into trying it. They ultimately did -- and with spectacular effect. Through radio intercepts, we found that we had great success."

Harry Baig, being especially adept at target acquisition information for artillery fires, picked up on the avalanche of target information and meticulously recorded them on 5 x 8 cards, one card for each 1,000 meter grid square. Harry's job was to organize targets, prepare them for destruction, and evaluate results. These included automatic weapons positions, mortar positions, anti-aircraft weapon positions, artillery, bunkers, fortitled areas and trenches, logistic dumps (by type), camp and assembly areas, truck and track vehicle parks, rocket sites, and launch areas. In a letter to the Historical Division, HQMC, Baig reported: "There were over 3,000 separate targets within a 15 kilometer radius of Khe Sanh." Hudson notes that "Harry had a head like a computer."

Pfc. Michael Archer, a 19-year-old Marine who spent the Siege in the COC bunker of 26th Marines as a night shift radio operator on the Tactical Air Control Party (TACP) radio net in the FSCC (Fire Support Coordination Center), recalled the arrival of Harry Baig, and it didn't take long for him to develop deep admiration for this remarkable Marine. "The first time I saw Captain Baig was outside the COC on his first day at Khe Sanh [23 Jan 68]. A recoilless rifle round had whizzed in and exploded, leaving a small crater. I watched as Baig strolled out and took a tape measure out of his pocket. He measured the length, width and depth of the little hole. He walked around the immediate area until he found a thumb-size piece of shrapnel, still so hot he had to bounce it in his palm in order to hold it. He examined the little piece of metal for a moment and then went back into the COC. There he looked at his map for a few minutes and then ordered an artillery mission onto a particular coordinate south of the base where he reckoned the gun was. I was amused at the time by this odd little man, and thought he was quite eccentric. After I saw the results of his later work, I have no doubt that he knocked out a NVA recoilless rifle team that day."

Just four days after Baig's arrival, he identified a NVA artillery headquarters between Khe Sanh village and the base. The air strike he ordered resulted in over 30 secondary explosions. "Two weeks later, Baig, while reviewing an aerial reconnaissance photograph, thought he recognized truck tire tracks converging on a certain location just south-east of Hill 471. I was looking over his shoulder at the photo and couldn't see anything. But I had, by now, become a believer in Baig's power of 'intuition.' As the bomber approached the target that night, I went outside to watch. It was less than two miles away. The little hill erupted in secondary explosions and burned and exploded for the rest of the night. Harry had found a major enemy ammunition dump in less than three weeks. It had probably taken the NVA years to stock it.

"I believe it was these early, crippling strikes against the enemy supply and command centers that disrupted the NVA plan for a major assault on the base. I think they would have had greater success had they attacked before February. Captain Baig's 'guesses' saved hundreds, maybe thousands of Marine lives."

Harry's area of the command bunker remarkably was known for generating calmness in visitors. Chaplain Walt Driscoll, the Roman Catholic chaplain on the base at Khe Sanh during the Siege, once remarked how reassured and calm he felt following a visit to Harry's area of the command bunker. "Everything seemed so rational, so under control, despite all the turmoil and chaos." Upon visiting him, Father Driscoll rendered him "a crashing British salute." Harry had become impressed with Navy chaplains serving Marine Corps units. His brother recalls, "My brother frequently talked about the amazing bravery of chaplains on the battlefield."

So impressed was Harry by Chaplain Driscoll's bravery as he moved about the base to minister to the men that Harry's mother later wrote: "He became a Roman Catholic only 5 months before he died. This was because in the heat of battle, he watched the R.C. priest join in to succor the wounded and give Last Rites. The priest became a real friend."

1Lt. Douglas Meredith recalls Baig, normally working there all by himself or with his assistant SSgt. Bolsey planning fires. Meredith frequently came "to work at the COC early just to listen to his analysis of the daily activity and the plans for the night as he rifled through his target cards. There was entirely too much work to be done. Under other circumstances, I would have listened to him for hours."

Meredith also recalls, "Quite often we'd jump up on the bunker at night and watch some of our fires that we'd planned for the night and see the secondary explosions. Kent Steen recalls Harry's bravery. "One night after arranging one of our artillery raids, Harry had run to the top of the bunker to witness our handiwork. A 'short' 4.2-inch mortar from our own battery flopped in between his legs. It had gone far enough to be armed but miraculously did not explode. I asked him if he had been frightened. He answered, 'No, it is not my time."'

Perhaps, it was this self-confident Úlan and lack of fear that inspired confidence to those near him. "Harry was fearless," writes Bernie Cole. Captain Baig went to Khe Sanh with four assumptions: (1) that the enemy would follow a master plan which had been promulgated from a headquarters, not on the field; (2) that the PAVN commander in the field at Khe Sanh could not and would not alter the battle plan to any significant degree, even if new conditions arose; (3) that the modus operandi was predictable and the general concept determinable once the opening moves were known; and (4) "that the plan encompassed classic siege tactics as practiced and studied by General Giap during and after the siege of Dien Bien Phu and as modified by experience gained at Con Thien in September 1967."

Encircling enemy troops unrelentingly persisted in rebuilding and advancing their trench and sap network approach to KSCB despite continuous, close-in air strikes of HE (High Explosive) and napalm, artillery -- even close-in B-52 strikes. Baig noted that three or four days later the whole area would be swarming again with NVA soldiers digging their Juggernaut: "The ant-like mentality of the enemy apparently made them continue rebuilding. What we were concerned with primarily was an enemy rush on the wire. We never thought the enemy would fight in quite the inept way he did. We really thought we could expect mass, human-sea attacks." For those who had the most data, who continuously poured over the various reports, the situation at Khe Sanh was indeed ominous. Kent Steen later noted, "We were all very concerned. The NVA made some big mistakes. They underestimated us. I don't think people realize just how close it was."

George Allen, the CIA's Deputy SAVA, was well conversant with the parallels with Dien Bien Phu, having been the U.S. Army's principal analyst during that battle. "I was able to make a connection between what happened at Dien Bien Phu and what happened at Khe Sanh and to understand the difference. That's one of the things that leads to my judgment about Khe Sanh having been 'the real thing."' Was the situation really so tenuous, so desperate in fact as well as in perception, by those on the ground and in the news media? Was it necessary for President Johnson to require each of the Joint Chiefs to pledge in writing that Khe Sanh would not fall?

In the decades following the Siege battle at Khe Sanh, some historians have questioned the reality of the size of the enemy threat at Khe Sanh. They dismiss any parallel to Dien Bien Phu as mere sensationalism. Those of us who were there know better. It may well be that any comparison with Dien Bien Phu (DBP) is faulty for not considering our logistic capability and commitment, as well as our tactical, aerial, and intelligence support. That, however, does not dismiss the unrelenting pursuit of a tactical reenactment of DPB on the Khe Sanh Battlefield by the PAVN! This was made evident in assaults on outposts (Khe Sanh Village and 861 on 21 Jan, 861A on 4-5 Feb, LangVei on 7 Feb, Hill 64 on 8 Feb) and from the construction of trenches, bunker complexes, parallels, saps and connectors and other "siege works" despite savage napalm and very close-in TPQ-10 and B-52 strikes.

Harry's effectiveness, both from his superior intellectual ability and education as well as his obvious possession of an intuitive "sixth sense," were not always beyond criticism. Did he go too far? Michael Archer, sitting at his radio in the regimental bunker, recalls an emotional encounter. "On February 27, as the enemy massed their troops and tanks to make the last big attempt to take the base, Baig erased the grease pencil circle on his map with a small piece of cheesecloth and ordered a B-52 strike on [Khe Sanh] Village. The area was completely obliterated. I was sitting right there when the Colonel stormed into the FSCC room that evening. I had never seen him so angry. He shouted, 'Harry, I understand that you just bombed the ville!' Baig courteously replied, 'Yes, Sir.' Lownds reminded him that he had strictly forbidden it. Baig calmly explained the necessity of having to do it -- tanks, assault troops [a regimental assault force was massing], and anti-aircraft guns. I will never forget the look on the Colonel's face. It was part anger at the insubordination and part resignation to the fact that it was done, and there was nothing he could do about it now. He looked at Baig for several moments and then said, quite seriously, 'Harry, I wouldn't want to be you when the war crime trials start.' The Colonel turned and left the room. The whole episode again made me suspect that Captain Baig was accountable to a superior officer higher up the chain of command than Colonel Lownds, and I think Lownds knew it, too."

As significant as the new gadgets of war were -sensors, new SIGINT devices and procedures -- far greater was the mental grasp and creative response of Harry Baig. As the ancient Biblical writer of Ecclesiastes noted: "Wisdom [in the sense of practical knowledge] is more useful than weapons of war." What Harry "saw" was not so much individual targets but the fluid process; for the NVA were intensely mobile, occupying a mortar or anti-aircraft or headquarters position for a short time, moving from one to another, and perhaps reoccupying the original position. The focus became not on where the enemy is but where they are moving through and to, where they could be projected to be, where their supporting reserve forces or retreat routes might be, given terrain conditions and extensive knowledge of NVA tactics. It involved thinking like a NVA, a feat at which Harry was particularly adept -- with deadly consequence for them and saving consequence for all the American defenders! The NVA the battlefield was dynamic, not static.

Interpretation and evaluation of the information together with familiarization and grasp of NVA tactics and analysis of terrain features enabled Harry to discern the dynamic battlefield and target it appropriately. The "total picture" or pattern that emerged involved locations of reserve forces, supply dumps, routes of reinforcement or withdrawal: these were targets as significant as detection of actual units or vehicles. An example to illustrate this may be seen in the NVA "siege works" of trenches to the southeast of the combat base, well known to all. "We knew full well the NVA were seeking to snuggle up to the Khe Sanh base within the 3-kilometer sanctuary that they thought they had from B-52 strikes," he said. Harry's interpretation of the sensor data proved especially significant to the defenders of Khe Sanh on Hill 861-A (Co E/2/26) the night of 4/5 February.

The NVA plan on 21 January, as revealed by Lt. La Than Tonc, indicated attacks on Hills 861 and 881S prior to the main assault on the combat base. During the nights of 3/4 and 4/5 February, sensors reported considerable heavy movement from the northwest of Hill 881S on a ridge to the west and southwest of the hill. The "Z" shaped ridge approaches the hill to a point about 3000 meters away and then runs south for some 4000 meters and then abruptly turns east, ending about 3000 meters due south of the hill. "During that phase of the siege, the S2 and FSCC personnel knew little of sensor accuracy and reliability, and I knew even less. And so, I embraced the theory that it would be folly to become erudite in one's ignorance. Therefore, believe that which the sensors purport to say. Thus, from the evidence of that night, I concluded that at least two battalions of infantry had reached a point 3000 meters to the northwest of Hill 881S; and that they had come from the direction of the known location of the 325C Division."

The total count of enemy troops reported by the sensors was estimated to be between 1,500 and 2,000 men. At first, Harry evaluated them to be resupply convoys and the FSCC reacted by attacking each sensor target as it appeared. However, the second night Harry's thinking veered to envision an enemy regiment and a possible attack against Hill 881S. Majors Coolidge and Hudson concurred that an attack in the thick mist was imminent. Harry knew that NVA tactical doctrine called for an attacking force to move to its assault position in echelons, make a last minute reconnaissance, and to attack in waves. If this were a regiment, then the force would be dispersed in regimental column, battalions on line (one behind the other). A target box of 1,000 x 300 meters square was drawn to the south of Hill 881S around a point where a large force, moving at two kilometers an hour (the NVA rate of march in darkness and mist), would have reached in the time interval since the activation of the last sensor. At each end of this block, a gently curving 1,000 meter line was drawn, extending towards and about the southwestern and southeastern slopes of Hill 881S. "For about 30 minutes, commencing at approximately 0300, 5 February, the five batteries within KSCB of 1/13 and the 4 batteries of 175mm guns poured continuous fire into various places of the block and along the two circumscribing lines at each end." At the end of the Siege, Harry briefed the staff at the ISC in NKP where Lt. Col. Peese, USAF, told Harry that the acoustic sensors in the area to the south and southwest of Hill 8818 had recorded the voices of hundreds of men running in panic through the darkness and heavy fog in a southerly direction. Defenders on Hill 881-S were oblivious to the nightmare and loss of life they were spared by Harry.

Hill 881s was spared a regimental-sized assault by NVA infantry that night. Unfortunately, two NVA battalions managed to creep to the northeast of Hill 861-A. There were no sensors near Hills 861 and 861-A, yet Harry readily took responsibility for his error in not recalling the NVA battle plan for simultaneous assaults on 881s and 861. "When the latter was attacked two hours later, I, the Target Officer and alleged expert on NVA doctrine, was caught flatfooted," he wrote.

In another letter, he wrote: "Once more, Marine NCOs and other ranks made up for the mistakes of the alleged brains of and on the staff, as they have done throughout our history." As it was, one battalion managed to close on 861-A. The second battalion "met a revolting fate. Attended to by one hour of shelling and air strikes which landed on all the possible assemble/reserve areas at the base of the hill."

That didn't infer that Harry did nothing! His immediate response effectively annihilated the second battalion from also attacking E/2/26 on Hill 861-A. Artillery and air support for Hill 861-A involved three simultaneous phases. 1/13 loosed protective fires on the slopes of the hill with three batteries, while a fourth battery concentrated on the area where the enemy movement was the thickest and then rolled down the slope to prevent the enemy from retiring or being reinforced. Secondly, Mark Swearengen, the 175mm Liaison Officer, went to Colonel Hennelly, Kent Steen, and Harry Baig and said, "Let me give you a 'wall of steel,"' and proceeded to direct his four batteries of 175s at Camp Carroll and the Rockpile to fire the "wall of steel" which embraced the base of the hill from the northeast. The objective was to saturate the area where the enemy reserve battalion was estimated to be. The "wall of steel" was moved slowly up the slopes until it reached a point 200 meters from the wire. "Within this space the battery from KSCB rolled to and fro, covering the area from where the attackers had come and into which Captain Breeding was energetically heaving them." Remaining batteries continued their protective missions, adjusted according to the defender's desires. The third phase of air strikes from the rapidly assembling aircraft involved TPQ-10 directed air strikes in the form of 200- and 300meter ripples dropped outboard of and parallel to the "wall of steel" to avoid check fires. "Bombs fell on known mortar clusters, possible assembly areas, and throughout the area to the far rear of the assault battalion. Enemy doctrine frequently positions the reserve battalion directly behind the assault unit. At all costs, the FSCC was determined to prevent their juncture. The reserve battalion never materialized."

Harry was primarily an artilleryman and his contributions to this aspect of the defense of Khe Sanh were significant. Harry wrote: "The artillery initiative was ours, and we held it throughout the siege, despite the worst croaking of sundry, inexperienced correspondents. Our motto was 'Be generous.' Had the NVA been capable of our artillery techniques, they could and would have blown us out of Khe Sanh. The siege clearly established not only the bankruptcy of the NVA master plan, but also the ineptitude of their vaunted artillery. The press never saw this clearly." Thus, more and more targets became apparent to Baig as the siege progressed. The NVA's rigid adherence to its doctrine and plan made it possible to determine remaining and undiscovered portions of a complex once part of it was located.

"Consequently," notes Baig, "we had far more known and confirmed targets than we could possibly use. Eventually, we began to attack them en masse instead of individually... Mortar and artillery positions, of which the former were not worth counting and the latter exceeded 160 separate sites, were bombed and shelled nightly in patterns of fire corresponding to NVA doctrinal position area engineering to destroy the unseen battery ammunition dumps."

An average night's pre-planned artillery fire might include 4-6 TOTs from 9 batteries, 4-6 Army and 10-15 Marine separate battalion TOTs, 40-50 battery multiple volley individual missions, 20-30 battery H&Is. Sensors accounted for at least 20 battery missions a night. Frequently, TOTs were fired into a recent Arc light area 10-15 minutes after the bombers had passed. A further issue of Arc lights were executed on most nights to catch the survivors.

Harry Baig's application of artillery tactics mostly suggested and devised by the creative men of the Khe Sanh FSCC defeated the enemy. According to the Regimental S-3, Lt. Col. Edward J. A. Castagna, they "turned the tide by hammering these people prior to their jump-off points. Several times we knew, or we figured we knew that these people were in assembly areas and actually were preparing for the attack. This was given to us through these sensor devices."

Young artillery officers such as Lt. William Smith stood in awe of Harry Baig. "I learned a lot from him about sitting down, and while everybody's racing around with a remarkable grasp of the obvious, you should be sitting down and looking back and trying to figure out what's really happening here, what would I be doing if I were over there? He taught me an awful lot. As a graduate of Ft. Sill, I had learned some of it in a theoretical sense, but I had never been able to use it on such a grand scale. Later, when I went to Camp Pendleton and ran operations with reserve units in the summer time as a regular, we never went anywhere without a Harry-type fire plan." Smith recalls, "Harry Baig used to call himself the composer and I said, 'Well, then, I'm the maestro!' I'd go to Harry and say, 'Could you write in a little bass? How about some 175s?"'

For his contributions during the Khe Sanh siege battle, Harry Baig was awarded a Legion of Merit, an unusual award for a junior officer to receive. The Citation reads in part: "Captain Baig exhibited exceptional professionalism and imagination in planning a highly effective defense fire plan for the Khe Sanh Combat Base. Displaying keen analytic and organizational ability, he skillfully compared all such data received with other current intelligence information, compiling an overall estimate of the enemy's disposition that, when utilized for target designation, yielded a most effective tool for the assignment of targets for supporting arms."

Following a 24-day leave to the United States, Harry returned on 15 June 1968. His next duty assignment was US Military Advisory Command Thailand, although his official record of service indicates he was assigned to the U.S. State Department for this duty. His mother recalls his happiness. He was finally able to be with his wife and daughter, and he wrote, "At last, I can have my family with me in lovely Bangkok, and my office is next to the Prime Minister."

"Officially, he was training an Intelligence Corps for the Thai Army but as he spoke French, he could slip into Laos in camouflage on secret trips," notes his mother.

His friend, Robert E. Coolidge recalls, "He was specifically recruited for that job, to do that [assignment] in Laos." During this time, he was promoted to Major (on 01 Dec 1968), and for his work he was awarded a second Legion of Merit, which noted: "His contributions...were of extraordinary benefit to the Royal Thai Government and to the overall furtherance of United States intelligence efforts in Thailand. These contributions were in fact of such a nature as to prompt the Prime Minister of Thailand to officially request Major Baig's normal tour of duty extended."

On his birthday, 13 January 1971, his mother had a nightmare of his tragic death exactly as it was to happen. The 39-year-old Harry, his 30-year-old wife Diane and his 10-year-old daughter Cecile were apparently asleep in their rooms on the fourth floor of the Imperial Hotel, Bangkok, Thailand, on 20 April 1971 when a fire broke out from an overheated grill unnoticed by a dozing cook, which in turn ignited grease and bottled cooking gas. Flames quickly entered the ventilation/air conditioning system. Mysteriously, the fire escape doors at each end of the corridor had been bolted shut from the outside, and speculation soon arose that this had been an assassination. Harry's mother notes: "When Munir's death was announced, some thought he must have been assassinated because of his work in Laos."

He, his wife, and daughter were all buried in a single grave in Arlington National Cemetery not far from President Kennedy's grave on Tuesday morning, 4 May 1971, following a service at Ft. Myer Chapel. To the amazement of his father, mother, and brother, several Generals (including Generals Cushman and Tompkins) were present. During a luncheon in the officers' mess, the family first heard of Harry's Laotian exploits. His father remembered, "The information slipped out at a luncheon in the military club given us by a Marine Major who mentioned what an authentic Laotian Munir looked once made-up and dressed in special clothes with his French accent. On asking what for, he answered those were special missions permitted by the President through Kissinger. As a life-long diplomat, I shut up! At that luncheon, I was also told that Munir was due to return to work with General Tompkins, who wept on receiving the news of his death." The family was invited to eat at the Commandant's residence at 8th & I during which General Chapman said, "Mrs. Baig, you have lost a son, but we have lost a special Marine." Kent Steen writes, "With the perspective of age, I realize the Marine Corps attracts strongly put together people, but Harry was clearly of another genius... I was more aware than most how near [i.e., tenuous] a thing our survival was. ..he couldn't get enough credit. The rest of us were probably interchangeable -Harry was one of a kind."

Harry's early death and highly classified work while at Khe Sanh has undoubtedly relegated him to an undeserved obscurity among veterans of the Khe Sanh Siege. As is apparent, however, many of us who survived that battle, perhaps all of us, owe our lives to this man. His great-grandfather may not have been able to save the fort at Bijapur, but Harry ensured that our fort at Khe Sanh would not fall. All of us who are Khe Sanh veterans owe this "prince from the Far East" our deepest gratitude!

One of those obscure and forgotten Marines, to whom all who survived Khe Sanh owe their very lives, was a Mongol prince re-clothed in the uniform of a U.S. Marine Captain -- Mirza Munir Baig, known to everyone who knew him as "Harry."

PUBLISHERS NOTE: The story of Harry Haig, written by Ray W. Stubbe, was slightly edited due to space constraints in this issue. If any member wishes the entire unedited version, they may contact Ray or I.

One other note. I was directly involved in the battle on Hill 861A on Feb 05 1968. I can attest that the constant and accurate artillery fire directed by Harry Baig saved us from being overrun that night. And I will, at this time, for the men of E Co, 2/26, say "Thanks Harry," may God be with you.