Khe Sanh Veterans Association Inc.

Red Clay

Newsletter of the Veterans

who served at Khe Sanh Combat Base,

Hill 950, Hill 881, Hill 861, Hill 861-A, Hill 558

Lang-Vei and Surrounding Area

Issue 52 Spring 2002

Short Rounds

![]()

Home

In This Issue

Notes From The Editor and Board Incoming

Memoirs

In Memoriam A Special Feature A Sprinkling Of Your Poetry

![]()

Veteran?

Some veterans bear visible signs of their service: a missing limb, a jagged scar, a certain look in the eye. Others may carry the evidence inside them, a pin holding a bone together or a piece of shrapnel in the leg.

Or perhaps another sort of inner steel: the soul's ally forged in the refinery of adversity. Except in parades, however, the men and women who have kept America safe wear no badge or emblem. You can't tell a vet just by looking.

What is a vet?

He is the cop on the beat who spent six months in Saudi Arabia sweating two gallons a day making sure the armored personnel carriers didn't run out of fuel. He is the barroom loudmouth, dumber than five wooden planks, whose overgrown fiat-boy behavior is outweighed a hundred times in the cosmic scales by four hours of exquisite bravery near the 38th parallel.

She is the nurse who fought against futility and went to sleep sobbing every night for two solid years in Da-Nang.

He is the POW who went away one person, and came back another -- or didn't come back AT ALL.

He is the Quantico drill instructor that has never seen combat but has saved countless lives by turning slouchy, no-account rednecks and gang members into Marines, and teaching them to watch each other's backs.

He is the parade-riding Legionnaire who pins on his ribbons and medals with a prosthetic hand.

He is the career quartermaster who watches the ribbons and medals pass him by.

He is the three, anonymous heroes in The Tomb Of The Unknowns whose presence at the Arlington National Cemetery must forever preserve the memory of all the anonymous heroes whose valor dies with them, unrecognized, on the battlefield or in the ocean's sunless deep.

He is the old guy bagging groceries at the supermarket, palsied now and aggravatingly slow, who helped liberate a Nazi death camp and who wishes all day long that his wife were still alive to hold him when the nightmares come.

He is an ordinary and yet an extraordinary human being. A person who offered some of his life's most vital years in the service of his country, and who sacrificed his ambitions so others would not have to sacrifice theirs.

So remember, each time you see someone who has served our country, just lean over and say, "Thank You." That's all most people need and in most cases, it will mean more than any medals they could have been awarded or were awarded.

Two little words that mean a lot, "THANK YOU."

(Author Unknown)

*****

Presidential Unit Citation is Awarded to:

Third Battalion, Ninth Marine Regiment, Third Marine Division

For Service set forth in the following:

For meritorious service in connection with operations against North Vietnamese Armed Forces from 17 June 1968 to 6 July 1968 in the Republic of Vietnam.

On 17 June 1968 the Third Battalion, Ninth Marines, commenced Operation Charlie. The assigned mission for the Third Battalion was to provide a workforce for the destruction of the Khe Sanh Combat Base, serve as the First Marines Regimental Reserve, and provide a reactionary force during the hours of darkness (one company on 30-minute standby and one company on one-hour alert).

The task of dismantling the Khe Sanh Combat Base was arduous, and although a difficult and strange assignment for an infantry battalion trained for offensive combat, the Third Battalion undertook the mission with aggressiveness, zeal, and enthusiasm.

The destruction work was extremely difficult and much of it had to be accomplished by manual labor. Bunkers were dismantled and destroyed; concertina and barbed wire collected and buried; and defensive positions destroyed. Salvaged materials were gathered, staged, and transported to Vandergrift Combat Base where items such as landing mats, steel posts, engineering stakes, and barbed wire were to be utilized to improve existing defensive positions.

The heat and dust were extremely adverse, and constant mortar and artillery attacks by the enemy while the men of the Third Battalion were operating and working with bulldozers and trucks in the area made the assigned mission especially dangerous and hazardous. Large numbers of bunkers and materials were destroyed. The remains of numerous vehicles and airplanes were buried, and a ground police of the entire area was conducted. When completed, the Khe Sanh Combat Base resembled a natural and undisturbed piece of terrain.

Through their indomitable spirit, intrepidity, and professionalism, the officers and men of the Third Battalion accomplished their mission in record time and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service.

For the Secretary of the Navy:

Commandant of the Marine Corps

*****

Tom:

During the Siege at Khe Sanh, L/Cpl Clyde Phillips and another Marine whose name I do not recall and I were setting in mines near the Gray Sector. This area was the responsibility of B Co 1/26 and the 37Th ARVN Rangers, located near the garbage dump. The NVA opened up on us with a recoilless rifle. There was a tank sitting near where we were working. I began pointing towards a big tree where there was smoke emitting. The men in the tank understood what I was trying to tell them. They fired one round at the tree where I had pointed.

A patrol of ARVN Rangers went out and checked the immediate area and returned with a recoilless rifle. They later reported that there were also two dead NVA near the base of the tree.

I would really like to know the names of that tank crew who saved our lives that day. My parents were attending a function at a Police Recreation Center named Tankersville when they met a former Marine tanker who also related the same story. I would really like to meet him, so maybe you could print this in the next issue of Red Clay.

Big John Pessoni

A Co 3Rd Engineers

Email: [email protected]

COMMENT: You got it, John. Good Luck.

*****

Publishers Comments: Kenny Pipes, former C/O B Co 1/26, became aware within the last year, that members of V0-67 had been honored for their service in Vietnam. As had SOG, they had been sworn to secrecy and their missions had been classified SECRET. After reading the following published article in which their service at Khe Sanh was recognized, Kenny Pipes contacted members of V0-67 and thanked them for their efforts on our behalf, I have listed those exchanges of e-mails and published the article which appeared in the newspaper November 09, 2001. It is important to keep our organization and its goals alive, so that everyone is made aware of the sacrifices made at Khe Sanh.

No Longer a Ghost Squadron

The Untold Story ofVO-67

By Mark Sauer,

Staff Writer San Diego Union Tribune

Printed November 9, 2001

Jim Koci tried to explain a Navy tradition known as toiling the bell, but his words foundered on the shoals of emotion. For a long, silent moment, the retired commander struggled to contain his tears.

Three decades and a half a world removed from Vietnam, Koci and most fliers from his Navy squadron still teeter between powerful feelings of pride and sorrow when they reflect on a mission once characterized by the words "top secret" and "suicidal." Another word, "closure," is often distained by stoic, aging warriors who have smelled the smoke and blood of combat. But closure is what members of Observation Squadron 67 will seek in a ceremony this month.

The crew of the San Diego-based destroyer Milius will present them with a bell engraved with the names of the 20 men from their squadron who died when their planes went down over Laos in 1968. Among those names will be the destroyer's namesake, Captain Paul Milius of Waterloo, Iowa, whose heroic efforts to keep his doomed plane airborne allowed seven of his men to parachute to a jungle rescue.

"We were a very close group. Because of the secrecy, it was like us against the world," said Koci, a pilot for one of the 12 crews of VO-67, a Ghost Squadron that officially did not exist. "I didn't think about what we did over there for 30 years. When the mission ended abruptly in 1968, we were scattered across the face of the earth and were told to never talk about it, not even to wives and family, and I didn't. But we were pretty successful. They said a lot of lives were saved because of us. It's time to talk about it."

They were submarine chasers, trained to fly low over the water's surface and drop sonar devices for tracking enemy submarines. They flew lumbering, old Lockheed Neptune P2Vs whose 76-foot long fuselage was fitted with thick steel and special target sights for this new secret mission. The men of what became Squadron VO-67 (the V stands for heavier than air and the O for observation) were abruptly ordered to North Island in 1967 at the height of the Vietnam War. They couldn't fathom their new mission. What's the Navy doing, the joke went, chasing Viet Cong subs in the Mekong River?

After a few months of training, they headed to a makeshift air base in Thailand. VO-67 would fly missions over the Ho Chi Mirth Trail, that infamous jungle supply route that snaked through neutral Laos and on toward Saigon in the south. But the United States' official position was that no fighting was taking place in Laos. Because of the Pentagon's secret war there, VO-67 would remain a phantom. From December 1967 to July 1968, VO-67 crews drove their Neptunes down from a safe altitude toward the thick jungle canopy and "inserted" thousands of listening devices along the trail with remarkable accuracy.

One type of sensor burrowed into the moist ground, its antenna popped up and blended into the foliage; the other, resembling a spike, was designed to hang up and dangle in the trees, like a microphone on a boom. American planes circled high above the Ho Chi Minh Trail and listened. The sensors were sophisticated enough to pick up conversations and even footfalls. When enemy troops, trucks and convoys were detected, air strikes were called in. The idea, conceived by the Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, was to create an electronic barrier to the north-south flow of troops and war material. It was dubbed the McNamara Line.

But the Neptunes' and their nine-man crews were sitting ducks for enemy anti-aircraft gunners. The fiercely defended trail was nicknamed Steel Tiger. The arriving Navy pilots told veteran Air Force pilots of small spotter planes that VO-67 expected to take losses as high as 60 to 75 percent. "We found it difficult to believe that anyone entering the war was pessimistic enough to expect losses of that magnitude," one Air Force pilot wrote in a recent memoir. "However, they told us their mission required them to fly their Neptunes' over the most heavily defended targets at altitudes of less than 500 feet above the road. We then wondered why anyone was optimistic enough to expect that 25 to 40 percent of the Neptunes' would survive."

For ten nerve-racking minutes at a time, the Neptunes (top speed 220 mph) cruised above the treetops in a straight line, "inserting sensors into the jungle. Then we'd open all four engines and go to the wall, zigzagging up and out of there," said Koci, 71, who spent 21 years in the Navy. It wasn't a pleasant ride for the guys in the back. The enemy fired round after round of .57mm and .37ram and anti-aircraft fire at the Neptunes. On January 11, 1967, a month after VO-67 began dropping sensors, one of the squadron's 12 planes went down; all nine aboard were killed. On Feb 17, it happened again and nine more airmen perished. Ten days later, Milius's plane sustained a devastating hit as it dropped sensors from an altitude of 5,000 feet. One crewman, John F. Hartzheim, died instantly. But Milius was able to keep the stricken aircraft aloft long enough for the remaining seven crewmembers to bail out. They were rescued: Hartzheim and Milius were declared missing and, a decade later, presumed killed in action.

Rescue teams in recent years have returned to Laos. In 1999, Hartzheim's remains were recovered and returned to his family. Last spring, rescue teams recovered human remains that DNA tests may show are crewmembers from the first VO-67 plane that crashed. No trace of Paul Milius has been discovered.

When the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive and Siege of the U.S. Marine base at Khe Sanh, VO-67 was called into action. Several enemy divisions encircled thousands of Marines. Sensors dropped in the jungle around the Marine base identified enemy strongholds for air strikes and artillery. When the siege ended, the Khe Sanh base commander said without the sensors, his casualties would have doubled.

VO-67 was a stop-gap mission, however. Once fast and modern Air Force F-4D jets were refitted and ready to take over, they replaced the old Neptunes and the squadron was quickly disbanded. Along with new orders and redeployment came the stern warning to never talk about what went on in the skies over Laos. VO-67 had lost 25 percent of its aircraft and about 15 percent of the aircrew in the squadron.

Nobody seems to know why it took 30 years to declassify VO-67's mission. But an article in a magazine for Navy veterans several years ago cited rumors of its existence. Then an ad in a Veteran of Foreign Wars publication in 1998 searching for crew members garnered several responses. The mission had been declassified; the men were flee to talk. "I answered that ad out of curiosity," said Gilbert N. Castenada of Chula Vista. Like the handful of other VO-67 crewmembers who settled in the San Diego area, Castenda said he followed orders and never spoke of the eavesdropping mission over Laos. He said it's helped him enormously to reconnect with his war buddies and attend two VO-67 reunions, the most recent in Reno.

"I didn't know where anybody was all of those years. I was completely on my own," Castenada said. "Bothered me we had to sneak back into the country and never tell family or friends what we did. For so many years, we had to keep this to ourselves. But you need to vent, you need to let it out."

The reunions have been cathartic for the 200 or so VO-67 members who attended. But nearly 60 squadron members have not been located, and the government hasn't been much help, said retired Navy Commander A.G. Alexander of Whitefish, Montana. Bureaucrats cite the Privacy Act, said Alexander, whose efforts were a key to reuniting VO-67. "I think that's just an excuse for them to sit on their rears. The basic problem is the government is so screwed up that nothing much works. Thank God for the Internet, or we'd never have found most of these guys." Alexander has made hundreds of phone calls and written scores of E-Mails and letters trying to track down VO-67 crewman. He said the squadron website www. vo-67.org, has been invaluable.

But reliving the war is not for everyone. Thomas Clark of Bonita hasn't made it to either VO-67 reunion. "I buried Vietnam after I got out of the service. I did that deliberately. But this effort to unite the squadron has brought a lot of it back," Clark said. Unlike many of his fellow fliers, Clark said the classified nature of the mission "kind of helped me. Vietnam was too painful. I lost some people I was close to. I tried hard not to get close to people over there because I knew if you lost that person, it would really hurt," said Clark, a gunner on Crew 6 who at age 34 in 1968 was among the oldest enlisted men in VO-67. "But you get close under those circumstances. You can't help it. Commander Alexander called me up one day, and we ended up crying."

Jim Koci said a few others they know of did not fare so well over the years, and they think it was due to their missions in Laos and the secrets they had to keep all these years. The old fliers of VO-67 have a bit of advice for Navy, Marine and Army commandos already deployed on secret missions in America's new war on terrorism. "I'd tell these guys that when they come back, when it's over, if they need to talk to somebody, do," Clark said. "But make sure it's somebody who truly understands what you've been through. Talk to someone who's been in combat. It took me a long time to realize how well I'd buried the whole thing."

PUBLISHERS NOTE:

Clark, just make one reunion, believe me you will walk away a new man, with a

whole different attitude.

*****

Kenny,

Thank You For Your Kind Words

A very good friend of mine was at Khe Sanh. His name is Louis DeMarco. He is in pretty bad shape right now due to seizures from a head injury he received there. He just moved from D.C. to Tennessee and is not back online yet. I will give him your address if you want. My son is an active duty Marine also stationed at MCAS Beaufort. He is towards the end of his second hitch. Used to be a weapons instructor at the Island for a couple years before Beaufort. Hasn't decided yet whether to stay in or not.

Earl D. Litz

Cape Coral, Florida .... "It's just paradise!"

Observation Squadron Sixty Seven (VO-67)

NKP/RVN October 67-June 68

OP2E Gunner/Photographer

*****

Ken & Group:

This is Dave Steffy -- the VO-67 troop. I passed along your last messages to the rest of the squadron and a least one of them would like more info about your reunion in Texas. He will attend, if possible. We still can't get to the websites you mentioned. If one of you can send me the information on the reunion, I will pass it along to him.

Thanks,

Dave

*****

Ken,

I t worked this time, great site. Did not have time to look at all of it right now but will later tonight. Las Colinas is not that far from Plano and is in the Dallas Metroplex area. If you guys want some of the guys from VO-67 to attend your reunion, I'm sure there would be several that would come. I know I would be honored to come and as it stands now, I could make it. Let me know what to do. By the way the VO-67 website is http://www. vo-67.org -- there are other links to related sights such as the recovery of our crew 2, which is ongoing as we speak. Well, got to go as wife is calling, talk to you later.

Lowell

*****

Ken,

I spent a couple of hours yesterday at the Khe Sanh web site. I was moved. I was an air crewman in VO-67 and flew several missions over Khe Sanh. From the air, it looked more like the moon with all the bomb craters everywhere. Let me tell you that I have the utmost respect for those of you who were there. At least we got to go back to a safe base every night. As I said, I read a lot about the history of Khe Sanh and am especially moved by the heroism described in the taking and holding the various hills around the base. My hat's off to you!

Semper Fi (Is an ex-sailor able get away with that?)

Rich DeCuir, Crew 2

*****

Ken:

My name is George Hilkens. I served in VO-67. I used to work with a guy who was also at Khe Sanh during that time, named Mike Helvie. Do you remember him? Also, another member of our squadron (Dave Thompson) retired from the Chicago police force, I believe. Small world.

*****

Ken:

I was the plane commander of Crew Six of VO-67. I will never forget, and neither will my crew, in my one and only flight over Khe Sanh. I left the squadron to go to Balboa for back surgery and ended up as having had a "silent" heart attack some time within the year. (The flight had nothing to do with it. ) We came in from the west over the mountains, down into a valley north of Khe Sanh, made our run, went to full power, and followed the valley to the east. We couldn't climb over the mountains, turned south at the end, and like water shooting out of rain pipe, we were right on top of Khe Sanh. There was a group of Marines standing there, and I remember seeing one Marine in particular, standing by himself waving to us. I can see that just like it was yesterday. I have always wondered if anyone remembers that? Kerry Bignail was my 2nd. Mech. He is a member of your Association.

A.G.Alexander, Jr.CDR.USN. (Ret)

328 Karrow Ave.

Whitefish, MT 59937

(406) 862-5161

[email protected]

*****

Ken and Thor,

Thank you for the info and kind words regarding VO-67. All of you on the ground at Khe Sanh were very special to us, and I can't begin to tell you of the satisfaction I felt upon reading your emails. The Marine Corps at Cherry Point, where I was a corpsman in '55-56, got me into Naval Cadets. I sincerely hope I was able to repay some of that debt at Khe Sanh. I was the plane commander/pilot of Crew 1, and still recall those Khe Sanh missions. I am confident that history will show how much we all owe to you Marines (and I hope you had some Navy Corpsman along) at Khe Sanh... A truly great job.

Ron Findley

CDR/USN/RET

*****

Ken,

My name is Lowell Shaw and I am a member of VO-67. I flew some (since I had aircrew wings), but was not assigned to an aircrew. I was what you guys would call a ground pounder with wings.

I tried your website, but it came back as not a good address. Could you update me on that? I live in PIano, Texas, a city just north of Dallas and I would consider it an honor to attend your reunion representing VO-67. I only have one problem. If it is outside of the Dallas/Fort Worth area, I would not be able to travel. I was laid off in August and still out of a job, so I could not afford to travel. But if the reunion is in the Dallas area, as I said, I would be honored to attend. By the way, I am a retired Chief Petty Officer (hope you don't hold that against me -just joking). I was a First Class Petty Officer when in VO-67 and worked on the aircraft electronic and electrical systems (as I said, flew sometimes but not as an aircrew member). I spent three tours in Vietnam, two with other Navy commands) and thanked the Lord that I got out all three times, uncut and unhurt. I have the Highest respect for any service person that went to Vietnam -- especially the Marines. You guys did a hell of a job and didn't get half the credit you deserve. Kind of like VO-67.

Please let me know where the reunion is, because there are a few more Texans around in other cities that might be able to go.

Hope to hear from you,

Lowell Shaw

2809 Peppertree PL.

PIano, Texas 75074

(972) 423-7792

[email protected]

VO/67 Member

![]()

A few years back, Dave Powell, a UPI photographer, sent me some pictures from his private collection. He was at the base and especially at Hill 881, where he took pictures of the guys and events that spent over 30 years in his closet. When the History Channel contacted me about doing a series on Khe Sanh, I thought of Dave's pictures and had Tracy, the History Channel editor, call him. He had a picture of Dabney, the one we used on the cover in our last magazine. Tracy contacted Bill Dabney, and he said he had the same picture. But when Tracy sent it to Bill, his eyes lit up, for he had never before seen this picture and didn't know it existed. I asked Dave Powell to write a little something for our magazine. Since then, he has been in contact with others who were at 881, and they listed him on their website along with others who served there at that time. Here is his response and follow up from others to his magnificent photos now out of the closet.

Jim Wodecki

*****

Jimbo,

I must say I am truly honored. I really think there must be some mistake. How does some adventurer with a camera rate being in the company of heroes? Most of whom fought and died for their country. But I am still going to have this framed and hung on a wall that Joelle will let me hang it on. Thanks very much to the officers and men of India Company.

Dave Powell

[Dave Powell's name was added to the roster of India Company.]

*****

Hi Frank,

Well, I don't have Major Chancey's address, so maybe you could forward this to him. I have been thinking a lot about what he said, and I want to thank him for what he said about the photos and about me. I did not know that it was the Purple Foxes that lifted me off the hill. But it has to have been. When I took all those photos of the Super gaggle, it was when I was leaving. To the best of my ability as I remember, is the airlifting of Dave Powell off Hill 881, which was in fact only a tiny part of the huge effort made that day by the Purple Foxes. I had never seen a Super gaggle before -- at least not from the ground. I got on the hill much the same way that I got off, with a bunch of choppers coming in like some huge Ferris wheel dropping men and supplies onto the hill. To watch it from the hill, was a whole new experience.

The first thing I saw (I had absolutely no idea of what it was that I was looking at) was this huge trail of what looked to me like white phosphorus, exploding across the sky in a long tight plume. The plume started to descend like a curtain, with chunks of it falling faster than the rest of it. I never saw the jet that created this high atmospheric effect. It seemed like it appeared out of nowhere. Then to my complete surprise, I saw and heard once again, Huey gun ships whipping around the hill, shooting the place up. I remember clearly thinking it was not a good idea for those gunships to be flying that low. Especially over such hostile terrain.

After all the time I spent on 881, the only aircraft I had seen were jets during the CAS missions. Well, I am taking photos like mad amidst all of this sound and fury. Here comes this flight of green choppers diving in and roaring away just as fast as they can. Someone is telling me to get into the trench that was on the LZ. It was probably that incredibly brave Marine who stood totally upright with both his arms in the air guiding the choppers in. I took his picture. It was like he was saying, "Here I am you little bastards, do your worst."

The so-called trench was about six inches deep. It was so shallow the three cameras around my neck made my back stick out like a camel. I distinctly remember rotating the cameras off to one side so I could get down lower in the trench. I kept thinking, who the hell dug this puny little excuse for cover. As a matter of fact it wasn't really cover. The best that could be said, it was concealment. As always, in situations like that, time slows down to a crawl. There were a few other Marines in the trench as well. As a matter of fact, I was laying head to head with a Marine. What really freaked me out, was that he looked so damn calm. I know it sounds kind of stupid, but I actually asked him, "Do I look scared, because you don't?" He said no, I didn't look scared. I was relieved for some strange macho ass reason. Finally, the bird that I am supposed to get on lands. I waited for what seemed an eternity for the ramp to come down. When it does, someone yells GO! GO! GO! I got up and I mentally charted the shortest distance between two points, and set a course for that ramp. I got up, and just like that movie "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" when they jumped off the cliff, I said to myself, "OOOH SSHHIIIIIT!!!" and took off running as fast as I could.

As I am racing toward the helicopter, this big Marine comes charging down the ramp. He decides the way I am coming to the chopper is also the way he is going to the trench. Neither one of us changed course, and we smashed into each other like two billiard balls. We bounced off each other falling backwards, and to our respective right sides. There we are, standing out in the open still looking at each other. I am pissed and he is smiling at me as if to say you didn't actually think you could come through me, did you, you puny little twerp? Hey, I was six feet, two hundred pounds. The guy must have been a football player or something.

Anyway, I took off again and as soon as I hit that ramp, I took a flying leap into the back of that helicopter. When I hit the deck, I started sliding like I was on ice. I slid all the way forward and came to rest face down between the legs of the Marine who is manning the M60 at the forward window on the right side. He was standing with his legs wide apart aiming the M60. I turned over and looked up to see this Marine with this deadly serious look on his face, staring down at me. I scrambled forward and sat up against the bulkhead of the flight deck of the chopper and tried to make myself into the smallest target as possible. It was then that I realized why I had slid so far forward so fast.

The deck of the chopper was covered with expended shell casings. It was like the whole deck was covered with marbles or ball bearings. I was staring aft at the open ramp as it slowly started to close. I was waiting for the sight and sound of holes being ripped through the chopper. I am saying, come on baby, let's get the hell out of here, please. The ramp closes and the engine starts whining. There is that brief moment when the chopper is not off the ground but seems like it is in the air at the same time, and then we are climbing with the engines roaring, and the bird is straining for altitude. The M60 is banging away, and shell casings are showering down on the deck, bouncing all over the place, until finally I can feel we are moving more horizontally then upward. It's getting quieter, and an overwhelming sense of relief comes over me. I said to the M60 Marine, "Well, I guess we made it." He didn't say anything but had a slight smile came to his lips. I took that as a good sign. I want to thank you, Major Chancey, and everyone with the Purple Foxes, because what I just described was only one day for me. But I realize for you it was a way of life. Frankly, I just don't know how you did it! What magnificent courage!! I will never forget. God Bless you all.

Dave Powell

*****

Dave,

Your narrative of your departure from 881S is superb not only as a realistic description of the event, but also as a tribute to the Purple Foxes. More broadly, your recollections and awesome photographs are indispensable to the overall history precisely because they come from a disinterested third party who had seen enough action in Vietnam to make valid comparisons. We grunts and zombies who did those things repeatedly assumed that the conditions came with the territory, since we had nothing else to compare them to. More to the point, your contributions add a spice to the history that makes it what Frank and I hoped it would be when we began -- a fitting tribute to those magnificent young men who endured and triumphed in those awful conditions. They now have a record, in writings and images, for their progeny and friends. They -- and I -- are both admiring of you for your courage in coming to the hill, and grateful for the record you preserved and have shared so magnanimously. On their behalf, thank you.

Regarding the photographs, I hesitate to impose on your already great generosity, but hope that I may have an 8x10 of whatever two photographs of me you think my bride would want, and 5x8 prints of those others in which I am a subject, however unflattering they may be. She was much taken by that last one in the CAS series. If you could also send a couple of your selection of Bob Arrotta, I will get them to him. We've been in touch over the years, but he is too modest and self-effacing to ask for them himself -- again, at your convenience and only as is easy for you. After all these years, any image is a treasure. Regards and Godspeed.

Gratefully,

Bill Dabney

*****

Reflections on Volunteering

By Michael Loehrer

When I arrived in Viet Nam in November 1967, I was assigned to a 105mm howitzer field artillery unit -- Bravo Battery, First Battalion, Thirteenth Marines. Many of the outfit were getting "short" and were glad for someone to take over the "FNG" details. When they needed a volunteer to go TAD to Gio Linh (a real hell hole), I was ready for something different and volunteered. I remember the beautiful convoy ride up Highway One, which ran through Hue, Dong Ha, and over the Cua Viet River, all the way to Gio Linh. What a magnificent country side! As we approached Gio Linh, the road became too muddy to proceed all the way into the base. We speculated whether Major General Tompkins, who was riding with us, would trek through the knee deep mud to the command post. Those who knew him, said he would, because he was "Old Corps", and he was a grunt's marine. Those who didn't know him, said no general officer would wade through that mud. It was deep, and it was nasty. So when the convoy bogged down, we all watched with admiration as he instantly hopped out and slogged up the hill to the CP. We immediately followed, filled with pride to literally follow in his footsteps.

We took a little incoming while I was there, but nothing

like the stories I had heard. There were a few patrols -- I remember one in

particular. The patrol ventured west toward Con Thien. It had not gone very far

before it was ambushed. I remember it was Mike Company, but I am uncertain

whether they were from the 26th or 9th Marines. They responded well, but

casualties were heavy, with several KIA. I'll never forget the expressions on

their faces as they carried their comrades back in makeshift poncho stretchers.

Gio Linh was a pitiful place, but nothing compared to what we would experience

at Khe Sanh.

The Unit to which I was assigned left Phu Bai and staged at Dong Ha in the afternoon of January 20, 1968. I was ordered to join them ASAP. As it turned out, half of our unit left that day -- the rest of us, the following morning. No one knew where we were headed, helicopters were everywhere. We hopped on one and headed west as the sun set. We traveled a long way and everyone had a different opinion where we were headed. I had been studying the maps of the area, and offered, my opinion, "The only place I know about over this far is Khe Sanh." It didn't mean much to us then, Con Thien and Gio Linh were more well known.

Because it was late in the day, we ate cold Crations and had no place to take cover. We were told to dig a good foxhole and expect incoming fire. The red clay soil was rock hard, and we didn't dig very deep before the sun went down. I remember trying to sleep that night in a shallow rut in the ground, my helmet tilted back cradling my head, watching the sky. I could see glowing objects coursing through the sky toward the southeast end of the base. I assumed they were incoming rockets. The other end of the base was taking a pretty good shelling, though nothing came near us.

We learned the next morning that the ammo dump had been hit. Sgt. Hewitt asked for volunteers to help clear the ammo dump of unexploded ordinance. I volunteered but found out the really dangerous part was already over. Weeks later, Sgt. Whitenight informed me that he and a Marine we only knew as "Smitty," moved a lot of ordnance that was still exploding. I think they got medals for it. I and the other volunteers helped other Marines who had previously volunteered.

I was volunteered for many other things, in true Marine Corps style. It was well into the Siege and a lot of people were getting tired of the stinking portable toilets. It seemed like I was the lowest in grade in our outfit for the longest time. I'm sure it wasn't true, but it seemed like it. However, I do remember getting volunteered to burn the drums filled with urine and excrement. A lot of people had been using ammo canisters, and sometimes their own helmets, for a toilet. We only used the above ground portable toilets whenever it was foggy or dark.

Under cover of fog one morning, me and few other unfortunate souls began the nasty job. You know the routine: drag the 55 gallon drums (cut in half) out of the back of the portable toilets, drain the urine, pour in the diesel fuel, light and stir occasionally with an engineering stake till all becomes ashes. We were only part way done when the fog lifted; sure enough, we started taking incoming. The person in charge said screw it, and we all fled for our bunkers. We were never ordered to finish, and believe me I didn't volunteer.

We were soon in short supply of communications people. Radio operators were normally good targets when on patrol. Fortunately, there wasn't much patrolling going on during the siege; some, but not much. However, we lost some of our radiomen because they were also wiremen. There were wires running from every howitzer to the fire direction control center. When we took incoming, these wires were often hit, and constantly needed to be repaired.

We

had a standing policy -- whether it was official or not, I don't know. Whenever

we took incoming, we always returned fire. Since we were surrounded, I think we

could just fire freely, and we wanted Charlie to know we could return whatever

he threw our way. We usually fired the previous night's harassment and

interdiction coordinates, if nothing else was in the works. Whatever the case,

the guns needed communication lines, and the wires often required re-splicing

during the middle of a barrage. A lot radiomen/wiremen were wounded while

performing this mission.

We

had a standing policy -- whether it was official or not, I don't know. Whenever

we took incoming, we always returned fire. Since we were surrounded, I think we

could just fire freely, and we wanted Charlie to know we could return whatever

he threw our way. We usually fired the previous night's harassment and

interdiction coordinates, if nothing else was in the works. Whatever the case,

the guns needed communication lines, and the wires often required re-splicing

during the middle of a barrage. A lot radiomen/wiremen were wounded while

performing this mission.

Word came down that we needed communications volunteers. So, I learned how to splice wires from a corporal named Wray. He was Polish, and that was his last name. That was the only portion of his name we cared to pronounce and, really, all I remember. He trained me and didn't seem to care that I was new and only a PFC. After showing me how to splice, he said, "That's all there is to it!" Being curious, I asked, "How do you locate the break in the wire?" With a grin, he said, "You just grab the wire and run."

What a trip! The next time we took incoming, it was very dark, he looked at me and said, "You're on your way." I grabbed the wire and started running. I couldn't see a thing. By this time during the siege, we all had a general idea of where things were. The only light there was came from explosions of incoming artillery. I remained in a crouched position long enough to find the break and fix it. I would find the closest hole, where I hid until the barrage was over. Ten minutes of sheer panic. Talk about extreme sports!

The next time I actually volunteered was April 4, 1968.

The Army was starting to sweep up the valley and Marines were preparing to move

out from the base. We had topographic maps of the area, but they were out in a

little trailer fully exposed to view, and it was broad daylight when someone

demanded those maps. Sgt. Hewitt asked for a volunteer, because every time

anyone appeared in broad daylight, we received incoming. Sure enough, I had not

been up in the trailer more than a minute or two, when a couple of rockets came

in. One landed very close. I don't remember hearing the explosion at all, but I

do remember being showered with red clay, and fighting for air through the dust.

A piece of shrapnel went through the biceps of my left arm, and a small piece

entered my side.

I was medevaced out and taken to Dong Ha, where I was patched up. They cleaned up my arm where the shrapnel tore a nasty hole, but could not locate the piece that entered through the arm-hole area of my flak jacket. What really freaked me out was the large tear in my flak jacket right over my heart. Thank God for whoever invented it -- saved my life.

The doctors were either concerned about the way my arm was torn up, or the missing piece of shrapnel in my side, and transferred me to Phu Bai, then Da Nang, then Thon Son Nut. Before I left Dong Ha, Major General Tompkins pinned on my purple heart. The same person who slogged through the mud up to the Gio Linh, four months earlier. He remains to this day one of the most inspiring people I ever met.

Three weeks later, I was released. I would still need three more weeks for a full recovery. Which basically meant an assignment of filling sandbags somewhere. I asked if I could return to my unit instead. They couldn't believe I would want to return to full duty and asked where my outfit was. I told them Khe Sanh -- they thought I was a head case. They could not fathom the camaraderie we shared. After much pleading, they released me to return to my outfit, and issued me a light duty certificate.

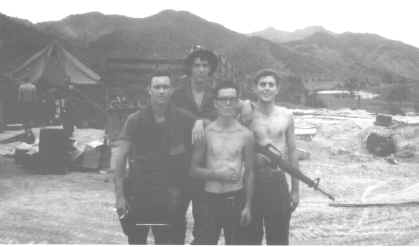

When I got back, the appearance of everything was shocking. After being in a clean environment the previous three weeks, the smell and filth were incredible. From January to April, we were living in holes in the ground with no showers and no way to clean clothes. While I was in the hospital, I bought a camera. When I got back to Khe Sanh, I took some pictures, which I forgot about until I moved recently and stumbled across them.

Spider Mike Loehrer

*****