| CRESTS OF JAPANESE WARLORDS' CLANS 2 |

| PAGE 1 | PAGE 2 | PAGE 3 | PAGE 4 |

The (oh, I'm tired of typing these same words all over this site!) Tokugawa shogunate (1603-1868) did a census of family crests, then put them all inside a book, and released a decree that the book (named 'bukan' in Japanese) was to be the official reference for making up new family crests. When the shogunate started to dwindle, the lowest-classed-but-richest merchants of Edo (Tokyo) were allowed to put on family crests on their formal dresses and such. Maybe the merchant family that today owns the largest chains of bookshops in Asia, Kinokuniya, was the first who used a crest, or perhaps it was their acquaintance Mitsui.

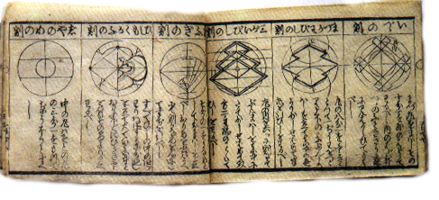

The Tokugawa era was one in which family crests were to follow the 'universal' pattern of being based on a circle. This was because the shogunate fixed the rules concerning where, when, how crests were to be put on people's dresses, and such things were called mon-tsuki (literal: moon of crest). Circles looked better anyway on jackets and so forth, compared to the warring period's crests that you have seen in the previous page, which didn't show any difference from the usual patterns on textile. Here are the crests of the Koide, Matsuda, Akizuki, Moniwa, Tomonobu and Obata clans, which are not exactly based on a circle:

According to the Tokugawas, women's dresses look best with round family crests whose diameter is 0.8 inch, while men's jackets were stencilled with larger crests, i.e. 1.80 inches. For convenience, sumo wrestlers were allowed to use 'gigantic' family crests, which all exceeded 2 inches in diameter. Those rules are still observed until this very minute.

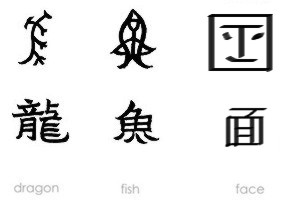

Then the Meiji Restoration came and everybody were not just allowed to use family crests but also, first of all, compelled to have family names (click here if you have no idea what I mean). So family crests experienced a big boom. It was because of the Meiji confusion that today there are so many Japanese clans and families unrelated to each other having the exact same family crests embroidered on their formal kimono (click here to see pictures). Because the Japanese use ideographs as their 'letters', between pictures lifted up as family crests and the written words in their script no yawning gorge ever existed. Glance a sec at the following examples of evolution of the Chinese and Japanese scripts. The pictures at the upper part are what 'dragon', 'fish', and 'face' were 'written' as, before they endured several hundred years of evolution into the characters on the lower part:

As far as the 'face' character goes, no one in the world would have foreseen its retrogressing move towards what you know since 1970's as smileys. Anyway, in 2002 there were approximately 6,000 family crests in use by the Japanese people, excluding corporate logos (if those aren't the owners' family crests). Most of them were still images derived from all sorts of plants. So Japan has been keeping its vegetarian symbolicism that originated in 600's by the landing of Buddhism, despite the many samurai crests that bear some birdy images, like the Shibata's, Akai's, and Hanabusa's:

Also those belonging to the families of Mori Ranmaru's, Kimotsuki, Nanbu, Hatano, Gamo, and Sasaki:

The oldest family crests in Japan are as a matter of course those of the Emperor's. There are exactly two of such crests. The first is the more imperial golden chrysant, the second is the pawlonia flower and leaves called 'kiri' that I have mentioned earlier. It looks like the ones on Toyotomi's curtains (left) and on Oda's vest (right):

After the Minamoto clan ascended (1185), the second crest got a bit pulled down to earth, because Emperors started to give licenses to use the pawlonia crest to Generals and courtiers. By 16th century the pawlonia was practically everybody's crest -- Oda Nobunaga (ruling between 1568-1582) used it, because he was given the rights to, though he never flaunted it outside his own castles. Toyotomi Hideyoshi (reigning between 1583-1599) even took it as his own clan's crest, and emblazoned it everywhere. Tokugawa Ieyasu (ruled since 1603 to 1616) got the same license, but he never used the pawlonia crest -- since it had been too Toyotomiesque by the time Tokugawa clan got the power over Japan.

Since 1500, it was normal for a samurai to have his clan's crest put on his garments, either as some elegant signs on the outer robes or vests, or to get printed noisily all over the entire pants or jackets. The habit stays on until today, though by now only on mortuary tablets and tombstones and formal black kimonos (click here for everything about Japanese clothing). Family crests certainly were a collective 'must' in the age of daily wars. And when they went to war, they fluttered not just their own clans' banners bearing the family crests, but also the banners with their superiors' crests, unless they were really big shots, namely great overlords like Oda Nobunaga, Takeda Shingen, and Mori Motonari -- because only in that position you wouldn't get anybody to tell you what to do. Overlords got to have their very personal battle-banner and/or standard precisely because everybody else also carried their clans' banners to wars.

Among the specimens above, Kikkawa Motoharu was the only one who still had someone else above him in the chain of command -- whoever led the 'Western Mori' clan (his dad Mori Motonari at first, and afterwards his nephew Mori Terumoto). But he was a smaller-sized overlord himself. So, in battlefields, he'd drag along quite a crowded air full of his own banners, too, carried by his vassals; so he needed some distinguishing sign to show who's in charge down there. Hence the personal standard. The similar air enveloped the presence of Ii Naomasa -- he had his own banners, his clan's crest, his legendary (or more precisely semi-mythical) 'Red Devil' squad's crest, and his boss', the Tokugawa's crest, all at once every time around. The Takeda Generals were more like today's Generals than lords over some feudal lands, but they faced the rest of the world like Ii and Kikkawa did, too. Plus their boss Takeda Shingen assigned names and banners to the divisions of his army, which added to the Generals' clutter of fabric in every war.

Now the hard part: even if without personal banners and bosses' crests, many samurai clans and families had more than one crest anyway. You have already noticed, I hope, that the Tokugawa and Matsudaira shared one crest, so did other clans whose origins were related. While at the same time several clans used two or three different crests at once, like the Takedas of Kai; the patriarch Shingen preferred the simplified flower petals that appeared on his banners and trinkets as nothing more than four squares, while his son Katsuyori (Oda Nobunaga's son in-law) opted for the flowerist version of the same crest. Katsuyori himself used two crests -- his father's and his mother's -- the Suwa clan's. Plus he also had his personal battle-banner and regiment's sign. So in every battle Takeda Katsuyori alone fluttered at least 4 different crests at once, and he wasn't the only one who did so.

The Takeda crests themselves are similar with some lesser warlords of their times, among which the Kazusa were of course their own relatives, and the Naito clansmen were one of their staunchest supporters, and Matsumae was more or less their playground. The crests appeared in Naoe's and Takahashi, too:

Click on to the next page for the glaring similarity among more samurai clans' crests. |

| Samurai Crests 1 | Flowers | Next Crests |

|

Site & Rap © 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 Nina Wilhemina

All rights reserved. Every borrowed image at this site is put for non-profit educational purposes only.

HOME

LINKS

LINKS

CONTACT

CONTACT

CREDITS

CREDITS

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Sources tapped for this page: Nihon Shakai no Kazoku teki Kosei (Tokyo: 1948); Kono Shozo, Kokumin Dotoku Yoron (Tokyo: 1935); Anesaki Masaharu, Nichiren, the Buddhist Prophet (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1916); Robert Cornell Armstrong, Light from the East, Studies of Japanese Confucianism (University of Toronto, Canada, 1914); Sasama Yoshihiko, Nihon kassen zuten (Yuzankaku, 1997); William Aston, Shinto: The Way of the Gods (London: Longmans, Green, 1905); Ruth Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1946); Charles Eliot, Japanese Buddhism (London, 1935); Futaki Kenichi, Chuusei buke no saho (Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 1999); Kiyooka Eichii, The Autobiography of Fukuzawa Yukichi (Tokyo, Hokuseido Press, 1934); Konno Nobuo, Kamakura bushi monogatari (Kawade shobo shinsha, 1997); Nukariya Kaiten, The Religion of the Samurai (London: Luzac, 1913); A.L. Sadler, The Beginner's Book of Bushido by Daidoji Yuzan (Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, 1941); A.L. Sadler, The Makers of Modern Japan (Tokyo: Tuttle, 1978); Satomi Kishio, Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles (NY: Dutton, 1924); Suzuki D.T., Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture (Kyoto: The Eastern Buddhist Society, 1938); Henri Van Straelen, Yoshida Shoin (Leiden: Brill, 1952); Robert Bellah, Tokugawa Religion; Sato Hiroaki, Legends of the Samurai (Overlook Press, 1995); Masaaki Takahashi, Bushi no seiritsu: Bushizo no soshutsu (Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku, 1999); Stephen Turnbull, Samurai Warlords (London: Blandford Publishing, 1992); Paul Akamatsu, Meiji 1868, Revolution and Counter-Revolution (Allen & Unwin, 1972); Nitobe Inazo, Bushido, The Soul of Japan (Tokyo: Tuttle, 1970); Paul Varley and Ivan Morris, The Samurai (Weidenfeld, 1970); Inoguchi and Nakajima, The Divine Wind: Japanese Kamikaze Force in World War II (Hutchinson, 1959), Seki Yukihiko, Bushi no tanjo (Tokyo: NHK, 2000); Amino Yoshihiko, ed. Edojidai no mikataga kawaruho (Tokyo: Yosensha, 1998). |