| BUSHIDO 2 |

| Makoto | Hagakure | Ukiyo | Seppuku | Zen | Kamikaze | Yakuza |

| Shinto | Tatenokai | Tanaka | Jibakutai | Jieitai | Mishima | Chu Hsi |

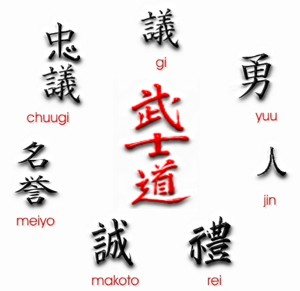

The Tokugawa Bushido preaches exaltations of the following items, which have been known as 'The Seven Virtues':

Or, if you insist, here are the same 'samurai seven commandments' or the 'bushido seven virtues' kanjiwise:

In the application of the virtues, a whole fat book can be attached to contain details. Benevolence, for instance, is to be spent on your sidekicks and deputies and relatives based on merit; thus whosoever doesn't deserve it would never get it. Symbolical rewards are to replace real-life useful trophies (such as hard cash, which was desperately needed by 99% of the samurai during the Tokugawa shogunate's reign, and whose stance in life was characterized by outstanding debts to the lowest-ranked subjects of the Japanese Empire: merchants and townsfolks). Your honor means your lord's or your superior's honor. But running away from battle was, no matter how un-romantic this is to you, not an offense against Bushido; since time immemorial, samurai always, as a matter of fact, ran when defeat was imminent, because what mattered was that you came back again to resume combat in another day. That's why Oda Nobunaga was mad at Tokugawa Ieyasu who ignored his letter that said "Just stay indoors, wait for me, and fight another day!" so that thousands of men of the Tokugawa Army were crushed to dust by Takeda Shingen in the battle of Mikata plains, 1573, simply because Tokugawa insisted not to run (click here for complete account of this battle). While the most famous Bushido virtue, loyalty, was not what you think it is. The impression that the Japanese samurai was clinging on to their bosses no matter what -- this is what has been implanted by samurai movies and books and sites, most of which are just romantic stories with some blood -- is wrong. It is equally wrong to download the notion that the samurai behaved against Bushido because they changed sides and changed bosses in the churning era of 16th century, which came to be glaringly naked on October 21, 1600 (click here). Loyalty could, and has been, given to the wrong objects all the time; when a samurai realized that, he should apply corrective measures, among which are leaving the boss, deposing him, or even whacking his head off (this subject has been dealt with at another page; click here). All other things adhered to namelessly by every Japanese warrior since B.C.E (see previous page) are all practiced unsparingly through application of the seven virtues, only the stress was, once again, the preservation of the Tokugawa clan, since 1600 after Sekigahara battle (click here). So here was the time when people like Miyamoto Musashi could rise as high as real heroes of wars; the Tokugawas' exaltation of duels for some fantastic notions of 'honor' made the idle and unemployed masterless samurai came to you today as larger than life. Do you really believe there was any sane reason why Miyamoto must fight against Yagyu, Ono, and finally Sasaki? Because there wasn't any. Such a thing was only possible under the Tokugawa shogunate's reign. No one bothered to tell the first caucasians who wrote about the Japanese samurai the truth that the word 'ronin', meaning literally 'the wave-men', was also used to refer to runaway slaves and peasants who neglected their fields. That's how you got to look at 'bushido'; don't use the usual so-called 'universal' system of thought. You got to use the Tokugawas' frame of reference or just accept the fate that you're lost.

Though the values espoused by the Bushido sound very Buddhist and Confucian, the core of it is Shintoist: it was all based on the characteristically Japanese filial piety, and not really the Confucian or Buddhist ideas about the matter (click here for everything about Shintoism). Just browse again the obese samurai archives: what wars were all about, how warlords came into existence, what a shogun's job-description was, what acts were highly valued in battlefields, and so on; they were all Shintoist. For instance, the most famous battlecry is perhaps this one from 1185:

Those third-person-singular forms are all referring to one man, you know; the 'I'. That long line delivered right before a man-to-man combat was Shintoist to the bones, evoking all the ancestral memory and kinship and allusions to the origins of the nation, besides all his very own titles and nicknames. So is this next most-famous battlecry from 1560's, nevermind the fact that it wasn't cried out loudly by the strikingly good-looking young lancer as his routine in every battle:

That it was a routine testifies to the fact that Maeda, the first lancer (one who came forward and started a battle) of the Oda Army, somehow, always managed to get rid of his opponents in every battle. He really was one heck of a guy. Anyway, he didn't invoke the name of Buddha and such; only his pedigree and his boss'. This is the filial piety a la bushido. That wars themselves got to be started that way is the way of the samurai. No wonder that the Hojo clansmen of 1274 got really disgusted that Khublai Khan's warriors shot at the Japanese soldiers riding toward them with the purpose of challenging individual Mongols to start the battle with. The synchretic characteristic of Bushido is apparent in writing, too. All of the Chu Hsi scholars and interpreters, who had helped campaigning for Bushido, were serious synthesizers: Hayashi Razan himself said "Shinto is loyalty to the Sovereign, and loyalty to the Emperor is Confucianism", and even others of an older generation also believed the same about Shinto and Buddhism, such as Kinoshita Junan (1621-1698), Amamori Hoshu (1611-1708), Muro Kyusho (1658-1734), Arai Hakuseki (1656-1726), so that their followers and successors unanimously upheld Bushido as a synchretic thing when it was born in 1717. So, the reason for a samurai to exist is Shintoist, while the attitude toward that existence is Buddhist. Each can't give you both in itself. Shintoism provides the Emperors and Empresses as the ultimate object to whom your life is for. Buddhism dishes out the view of that life itself as something too impermanent to get you attached to it. The spiritual cocktail these two made is perfect -- it is Bushido -- whose more practical manifestation is based on Confucianism and Chu Hsiism, whose jobs are to tell you what to do to fill what you live for (the Shintoist reason) according to your view of life (the Buddhist view). But here is a thing that has been confusing Bushido-trekkers for ages: the real Bushido was propagated by the opponents of the Chu Hsi school, too. Nonetheless, this is the thing that can explain the confusing Meiji versus Tokugawa war, 1853-1890 (click here), as well as the insurgence of military clots in 1930's. Exactly because 'loyalty to the Emperor is Confucianism (or Buddhism) as well as Shintoism', the Tokugawa clan's reign was seen as illegitimate at last, because it had broken the vow of loyalty; you might have never guessed it but Bushido was a reason of the Tokugawa shogunate's own downfall in 1868. This started with people who wrote about 'the way of the warriors' in a different way from the Tokugawaist scholars', focusing the filial piety toward the Emperor: Yamazaki Anzai (1618-1682), Nakae Toju (1608-1648), Yamaga Soko (1622-1685), Ito Jinsai (1627-1705), Ogyu Sorai (1666-1728). Their successors wrote and propagated Bushido in a different way, too, when their time came after 1700, while there were also men whose gaze was extended beyond the Japanese borders, too, like Hiraga Gennai (1732-1779), Yoshida Shoin (who even went to Europe illegally in 1859), and Honda Toshiaki (1798), whose Bushido was more 'universal' than the Tokugawa's. Yamaga Soko, by the way, was the one who taught the way of the warriors to the worldwidely-known 47 ronins. Anyway, the confusion shouldn't be. The opponents of Chu Hsiism are Shintoists; they, too, upheld the same basix as the Japanese Chu Hsiists. As you can see in the Meiji versus Tokugawa war, while all things crumbled down, both sides never, ever, deviated from the common principle that it was the Emperor they were serving and dying and killing for. The Shintoist core of Bushido was above politics, which was something natural because it is above logic.

Now the dark side of the same coin: In the application of bushido there has always been this streak: disdain towards the class of merchants. Scorning this particular class was simultaneous with practicing bushido, no matter how socially uncouth this sounds. Some, like Yamagata Hanto (1746-1821) actually wrote such things down:

Hayashi Shihei added to his teachings:

And Takano Shoseki said:

Yamaga Soko chimed in:

All this stemmed out of the infamous Sword Hunt Edict of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's in 1894 that basically divided the Japanese into samurai, persons of religion, the Imperial House, and none of the above. Tokugawa Ieyasu copied it, added details to it, and applied it for real, and his offsprings were conveniently left with a sharply-classified people to rule (click here for the complete social ranks in the Tokugawa world). All the Tokugawaist laws were applied differently to different socio-political classes; a crime worth capital punishment when committed by a merchant was a minor offense when the culprit was samurai, and vice versa. So, don't ever think that it was cool as far as the warrior class was concerned. Back to the subject; the economic thought of the Tokugawa shogunate since 1603 until 1868 can be summarized as contempt towards economic thoughts. That's why the debts of the samurai class had broken all records: 500 times the currency in circulation in 1700. They just stood no chance in dealings with merchants.

The Tokugawas' total incomprehension of economics, the most distasteful subject in their eyes, made them stupid enough to always try to solve economic problems with.....Bushido. Whenever farmers revolted because the harvest failed and they were starving, the Tokugawas whacked the farmers off and then released decrees prohibiting merchants from wearing silk robes. Whenever samurai debts became much too unpayable, they released edicts that said samurai must not spend a dime more on geisha. Whenever the pawnbrokers and money-lenders showed discontent as the samurai debts were declared as cleared by the shogunate, the Tokugawas launched pamphlets that said the samurai had to remember how their ancestors lived frugally in the past. And so on. I hope you got the idea of what 'moral remedy' was on the Tokugawas' minds, and what economic problem there was that would never got solved that way. By 18th century, basically merchants and townsfolks ('chonin' in Japanese) ruled, all over the Tokugawa shogunate's direct territories. This didn't include the spheres outside it, belonging to the 'Lords of the Outsiders' ('tosama') -- the clans that never really submitted to the shogunate in 1600 -- for instance the Maeda clan of Kaga, the Shimazu clan of Kyushu, the Asano clan of Shikoku, and so on (see the composition of Meiji warlords versus Tokugawa warlords at another page). Those clans had their own Bushido and their own economics and both were much better than the Tokugawas'. The Maedas did their own agrarian reform, and during the nationwide famine the farmers in their province never came near to starvation. The Shimazus trained their own samurai based on Bushido 'in the purest meaning', i.e. centering on the Emperor, and nowhere in it the Shogun was accomodated. The Asano clan's political view, naturally quite the opposite of the Tokugawas' Bushido, made the territory a place where the bureaucratic characteristic of the Tokugawa shogunate's reign was never implanted. Why did the Tokugawa shogunate do nothing about all those 'outsiders'? Because they had no power to do anything whatsoever about it. The Tokugawa shogunate couldn't touch the Maedas, the Shimazus, the Asanos, the Moris, the Kurodas, and so on -- all the clans which were Oda Nobunaga's and Toyotomi Hideyoshi's vassals -- because Tokugawa Ieyasu's testament said so, and all the Shoguns after him obeyed the testament word for word. Moreover, militarily-speaking, the Tokugawas wouldn't stand a chance if they fussed about those 'subdued but never submitted' warlord clans. All the 'Lords of Outsiders', no matter how much they were suppressed by Tokugawa Ieyasu, Hidetada and Iemitsu, were dangerous people to quarrel with. Morally, theTokugawas didn't have a legitimacy to annoy those warlords, since their laws were carefully made so as to be never against the Tokugawas' laws. Economically, they didn't even have the right to tax the 'outsiders'; the Tokugawa taxation applied only to his own clan's territories. The 'outsiders' duty was only to send some tributes once a year. Tax in their provinces was their own biz. That's why Maeda and Uesugi Chiefs during the Tokugawa era had been able to keep tax to the minimum any time their farmers got bad harvest, while the Tokugawas, on the contrary, raised it; and this was why Maeda villages were tranquil and Tokugawa's villages got cramps because of peasants' revolts. So, now you got the pic of how things were between 1603 and 1868. That 'merchants ruled' within the territories of the Tokugawas happened as a historical necessity of having probably half of the empire crowding in the cities; but the basis of bushido was agrarian: bushido thought highly of farming, though not of farmers. That's the kind of minds that gave birth to and upheld the 'way of the warriors', a.k.a bushido as you know today.

After the Meiji Confusion, 1853-1890, the series of 'the last samurai' clashes against the americanized Imperial Army have always been referred to as some 'bushido' stuff. But those 'last samurai' themselves never used the word 'bushido' in writing their lists of grudges against the new order of things; 'bushido' as a term wasn't used either by their enemies in this violent era. And no one actually browsed the Hagakure in order to cite it in their rhetorics. The last item came from the fact that rhetorics had never been of any value to the Japanese since 660 BCE until 1868. Really. They even despised it. Building up arguments and debating things were always alien to the Japanese, most of all the samurai class; that's one of the reasons why Japan generally thought that Christianity was too noisy to be of any good, and missionaries were taken to be loud windbags who didn't know how to behave properly (see History of Japanese Christian warlords & samurai at another page). So, because the ones who concocted rhetorics were Meiji supporters, nothing like 'Bushido' was mentioned. The people who might have mentioned it were generally their enemies. Therefore between the lines the rhetorics for 'open policy' at the end of 19th century were 'Bushido is archaic'. But right after Emperor Meiji won the last of the random civil wars in 1890's, the administration picked up the 'Bushido' again -- not because they loved it or anything, but because it was useful for the 'modernization' (americanization, to be exact) campaign which was, paradoxically, thickly coating the 'traditional' Shintoism. The ancient system of belief was overhauled so that the faith in the heavenbound monarchy became a personal cult of Meiji. And His Majesty's so-called 'advisors' wanted overseas war; hence 'Bushido' was re-released to support this imperialist streak. Hence China was invaded, and Russia defeated, and Korea was for the zillionth time coveted. The book Hagakure became all the rage as the Meiji regime entered the 20th century. It was THE must-read for any manowar, and between the two World Wars it was practically the only reference everyone -- Japanese or not -- resorted to, simply because the Japanese had to explain themselves again to non-Japanese in this era. The thing to get explained -- the mixture of militarism, fascism, chauvinism and imperialism -- was, once more, simply lived at home without any need to even talk about it.

In the attempt to explain the current Japanese frame of mind to Americans and such, Hagakure was taken as a reference; not as it was but after being refashioned and reinterpreted by dozens of people in 1920's. It, as a matter of fact, did a good job. 'Bushido' was to be everything to the kamikaze pilots who converted Pearl Harbor to smokey debris. 'Bushido' was why Anami Korechika refused to lead the Japanese Army's revolution against Emperor Hirohito's unbearably shameful admittance of defeat and horrific denouncement of the divinity of his ancestry. 'Bushido' was, though, also the driving force behind the young officers of Japanese Imperial Army and Navy of 1945 who wanted Anami to lead them in the first place, and motivated the Emperor to opt for dodging the risk of losing more lives among his people. So, two sides in the Japanese wars always consisted of two clots of Bushido adherents, and this is why you can see monuments, statues, plaques and such everywhere all over Japan now, celebrating everybody, even insensible opportunists like Akechi Mitsuhide and numbskulled windbags like Ishida Mitsunari. The nature of the 'way of the warrior' that has been giving headaches to caucasian observers is precisely that it can mean two things that run against each other for the one and the same reason and out of the exact same reasoning. Take this for example. On February 26, 1936, Captain Nonaka Shiro of the 1st Division of the Japanese Imperial Army in Tokyo, assembled 1,500 soldiers in an attempt at a coup. These soldiers -- none was higher in rank than Captain -- stormed into some people's houses and killed the targets -- bankers, businesspersons, consultants, Ministers, and the Prime Minister Okada Keisuke (who was saved because his cousin Colonel Okada Matsuo, who looked like him, took his place as the target). Then Nonaka and company fortified themselves. This is what Nonaka wrote as his manifesto:

The 'Showa Restoration' referred to by Captain Nonaka was the sway towards some peace under the reign of Emperor Hirohito at the time. The content, the passion, the tone of the manifesto was almost an exact echo of what the Meiji versus Tokugawa war of 1853-1890 resonated throughout history -- both the pro- and the anti-Meiji said the same. It was also the case of Nonaka's times. "In the name of the Emperor, stop this nonsense and disband!" shouted the Minister of Interior, Goto Fumio, across the barbed wire. "In the name of the Emperor, you stop your nonsense and leave us alone!" Nonaka replied. It would have been a bit funny if it were not so bloody. Nonaka's 1,500 men were surrounded by the Imperial Guard and the rest of the Army, plus the Navy -- which never had any nice relation with the Army as a whole. What both sides thought and felt was the same, yet there they were, pointing guns at each other, until Emperor Hirohito -- whose reign was marked by the worst of Japaneseness -- got sick of being dragged into every fratricidal event hitherto committed or attempted by every sort of groups, and pressed the Army to take care of its own wayward kid. After a long campaign (via leafets showered to the Nonaka 'HQ'), a big chunk of the rebels surrendered. They, as was promised in the leaflets, were free to resume their original posts. Nonaka was executed, though; so were members of his inner circle, while a lot others were put behind bars. Emperor Hirohito hadn't seen the last of such 'in the name of the Emperor' thing. The last that he would have to bear would happen on November 25, 1970 (click here), even though there were other events afterwards that smacked of the same thing.

Hagakure, the Bushido Bible, was one of the books Captain Nonaka and all others perused when getting drilled at the academy. Notions like 'in the name of the Emperor' came from there. The Japanese understood Nonaka as well as they understood Minister Goto, and they cheered the Imperial Guard as well as Nonaka's company. That 'everyone is a hero' wasn't a big deal to the Japanese, since the same thing happened over and over in their history, but how could they make outsiders see what they saw? That was impossible, even as, by 1936, interpretations about Hagakure had been published and distributed in caucasian hemisphere, and Bushido was made current, and both really got simplified and squeezed down like Bibles for kids. Yet, nobody outside Japan could really comprehend the endless tale where no side was wrong in every war. This notion stays evergreen; even this minute, millions of non-Japanese out there see samurai wars and Japanese wars in general was nothing but killings and winning for the stronger between the two, without any 'moral' value whatsoever attached. Understandably, after Hiroshima and Nagasaki were atom-bombed in 1945, Hagakure was shunned as a big bad wolf of peaceful Japan, until that foggy morning of November 25, 1970 (click here for what happened that day). Strictly speaking, then, 'Bushido' is something that got released in the most churning decade of modern Japan, when virtually a mass protest and an attempt at a military coup were done every Wednesday or so: 1930's. Because only since 1930's the word became attached to the simplified 'way of the samurai'. The Bushido was again re-fashioned since January 8, 1940 -- this was the day the Minister of War, General Tojo Hideki, distributed books containing his formula of military ethics, called Sen Jin Kun. It it, the Meijian Bushido was remade, and the Tokugawanist Bushido 'sampled' (as in rap songs), to suit the purpose of the emerging Neo-Imperialism, Neo-Fascism, and Neo-Militarism. The highlighted part there was how to die for the glory of Emperor Hirohito, which was the same as for the glory of Japan. And what you know of 'Bushido' now was never fixed for good before 1970 (click here). Since 1970, the Bushido has been laddled out all over the globe in the squeezed-down version of all the Tokugawanist traits, Meijian trends, and Tojoist fervor. It is this bushido that gives you, for example, the very very really wrong impression that a samurai, rather than retreating or surrendering, will instantly die. That's a hijacked and twisted point of the original 'way of the warrior', and a warped part of the Hagakure. I have explained earlier somewhere else at this site why so. Another example is even readier: your admiration of Miyamoto Musashi as Bushido on two legs. Once more, kendo is not bushido, and the reverse is equally wrong. But all those bulks like "Bushido for Company Management", "Samurai CEO", and so forth, have been let to saturate the international mind, so that this minute anyone interested in learning any Japanese martial art thinks of himself as an adherent of Bushido. Even just death is made into Bushido -- this, too, only happened after 1970, because the deaths of 1945 were Bushido. Now any masochist-suicidal critter can claim he is following Bushido, and this idea will sink in as long as he really does have the guts to cut himself open, because Bushido today makes it plausible. Endless fuss around which part is to be correctly called what, of the 'traditional Japanese samurai armor' ('yoroi' has been an ubiquitous word since 1990), too, is taken as evidence of adherence to Bushido. Real samurai, you know, never cared about such trivia, especially if minded by persons who have never killed anyone for the glory of Japan. That whacks away a great chunk of its charm, but that's real history.

Anyway, you have probably heard of too many Japanese samurai by now (at this site alone, according to a visitor, there were 870 names -- and that was in 2002). But not all samurai, no matter how great they are as legends (see the Samurai Legends page), have been seen as the ones to look up to when it comes to the best practice of Bushido. Why? Because to be such a role model, you have to adhere to all the principles of this class thoroughly. One aspect of it was neglected, you'd never make it, and the peak of your achievement would have been as 'only' a legend. Yet, a few individuals, among the millions of Japanese warriors, between the year 660 before Jesus was said to have been born until this very day, managed to get immortalized as the ones in whose very veins the Bushido was once alive -- -- to be admired, respected, and made into role-models just by being themselves. They lost time and time again in numerous battles; they accumulated a lot of wounds; they died in vain; but, over time, history never forgot about them. Without being told to, people, one generation after another, just came to their mossy cenotaphs bearing flowers every once in a while, since a thousand of years ago; they tell their kids to try hard to emulate those lives that were here before; they were constant sources of inspiration to every sort of arts. Who are these select few? To those who have been to more than 10 pages at this site: No, Oda Nobunaga is not there (unprintable words follow). Not even Tokugawa Ieyasu. Perhaps you have never even heard about some of them before. Click on to the next page. Or.....

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Previous

Page: |

NEW Black Dragon Society |

Next

Page: |

|

Site & Rap © 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 Nina Wilhemina

All rights reserved. Every borrowed image at this site is put for non-profit educational purposes only.

HOME

LINKS

LINKS

CONTACT

CONTACT

CREDITS

CREDITS

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Sources tapped for this page: Nihon Shakai no Kazoku teki Kosei (Tokyo: 1948); Kono Shozo, Kokumin Dotoku Yoron (Tokyo: 1935); Anesaki Masaharu, Nichiren, the Buddhist Prophet (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1916); Robert Cornell Armstrong, Light from the East, Studies of Japanese Confucianism (University of Toronto, Canada, 1914); Sasama Yoshihiko, Nihon kassen zuten (Yuzankaku, 1997); William Aston, Shinto: The Way of the Gods (London: Longmans, Green, 1905); Ruth Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1946); Charles Eliot, Japanese Buddhism (London, 1935); Futaki Kenichi, Chuusei buke no saho (Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 1999); Kiyooka Eichii, The Autobiography of Fukuzawa Yukichi (Tokyo, Hokuseido Press, 1934); Konno Nobuo, Kamakura bushi monogatari (Kawade shobo shinsha, 1997); Nukariya Kaiten, The Religion of the Samurai (London: Luzac, 1913); A.L. Sadler, The Beginner's Book of Bushido by Daidoji Yuzan (Tokyo: Kokusai Bunka Shinkokai, 1941); A.L. Sadler, The Makers of Modern Japan (Tokyo: Tuttle, 1978); Satomi Kishio, Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles (NY: Dutton, 1924); Suzuki D.T., Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture (Kyoto: The Eastern Buddhist Society, 1938); Henri Van Straelen, Yoshida Shoin (Leiden: Brill, 1952); Robert Bellah, Tokugawa Religion; Sato Hiroaki, Legends of the Samurai (Overlook Press, 1995); Masaaki Takahashi, Bushi no seiritsu: Bushizo no soshutsu (Tokyo: Tokyo daigaku, 1999); Stephen Turnbull, Samurai Warlords (London: Blandford Publishing, 1992); Paul Akamatsu, Meiji 1868, Revolution and Counter-Revolution (Allen & Unwin, 1972); Nitobe Inazo, Bushido, The Soul of Japan (Tokyo: Tuttle, 1970); Paul Varley and Ivan Morris, The Samurai (Weidenfeld, 1970); Inoguchi and Nakajima, The Divine Wind: Japanese Kamikaze Force in World War II (Hutchinson, 1959), Seki Yukihiko, Bushi no tanjo (Tokyo: NHK, 2000); Amino Yoshihiko, ed. Edojidai no mikataga kawaruho (Tokyo: Yosensha, 1998). |