| Back to Mycroft Holmes Title Page |

THE TRIDENT SHAKES Mycroft is also available at sambonnamy.110mb.com

April 24th - May 12th 1891 |

|

| In which Anna makes waves to rescue Mycroft from a hot and steamy position | © paperless writers 2000 - 2006 |

|

THE TRIDENT SHAKES June 26th - 27th 1897 Footnotes in red are clickable Sunday June 27th 1897, 12.30 a.m. I've just seen the article that the Times man intends to wire to his paper for Monday's edition. His main facts are wrong, but for the sake of keeping the peace in Europe we shall all have to pretend otherwise. It never fails to amaze me that men can be as stupid as was Colonel Fritz von Tarden today - or, rather, yesterday, since it's past midnight. After all, if he had succeeded in stealing the fastest vessel in the world from under the noses of the Royal Navy, we should now be preparing for war with Germany. Most of our party have gone to bed. "Gone to their berths" is what I should write, since we're on board a ship. Surprisingly, I haven't felt seasick once, even though I spent the morning being whirled along at over thirty knots. How easily I write that down, who yesterday thought that knots were what you tied parcels with. I'm too excited to sleep, so I shall sit here in my cabin and write down the truth of what happened to the Turbinia, the fastest ship afloat and by now the most notorious since the Mary Celeste. My story begins a fortnight ago.

Monday June 14th - Wednesday June 16th Because Stephen has estates in Northumberland, he knows some of the big men in engineering and shipbuilding in the North. The Armstrong family, for example, who have huge engineering works in Newcastle upon Tyne, are among his friends, and so is Mr Charles Parsons, who owns works in the same town where he experiments with new types of boat. 1 One morning, Stephen pointed out a sketch map printed in the previous Saturday's Times. "Look, Anna, there's the plan of the Review. I meant to show you this the other day. That's where Parsons will be with his yacht. He's hoping to show it off to the Prince. Isn't it exciting?" I looked at a plan of the proposed Naval Review for Her Majesty's Diamond Jubilee celebrations. London had been buzzing with preparations and gossip for weeks. 2 "Over a hundred and fifty ships in four lines at Spithead," said Stephen. "Twenty-five miles from end to end, and we're to be part of it." "We? Mr Parsons and you?" "Parsons will be aboard his yacht. You and I, my darling, will be aboard the Danube, celebrating the occasion in grand style." "Whose ship is the Danube?" "Royal Navy, I think, although I'm not sure. But it will be given over to members of the Lords that day, and I shall be there, as a junior minister, and of course you'll be with me, won't you?" "What, with the noble lords? As your mistress? They won't let me near the boat." "Ship." "Ship, then. What does it matter, since I shan't be there?" "Don't you want to go?" "Oh yes, of course I do. I want to be wherever you are. But, darling, don't you see, I won't be received. I'm persona non grata in polite society. Who am I, after all? A common actress, when all's said and done." My word! I was feeling at odds with myself that day, and it wasn't even that time of the month. Stephen took my hands in his. "Look, Anna, there'll be nothing to stop you joining me. I can bring whom I like. One day you'll be my wife, so you may as well accustom yourself to coming with me on trips like this." Yes, one day, when Emmeline condescended to agree to a divorce. Stephen had grounds for divorcing her, for he knew of her adultery with Mycroft. But he refused to prosecute a case for fear of the scandal. Emmeline had developed a fiery temper and was not averse to outraging polite society, as Mycroft himself had discovered when she tried to get into the Diogenes one day. Stephen rumpled my carefully-brushed hair, kissed me and went off to Whitehall. Later that morning he called me on our newly-installed telephone. "Anna, can you hear me? Good. I have a request for you that you'll find strange, but will you simply comply, darling, without any questions?" I assented, puzzled. In the background I could hear the clack of typewriters. "I want you to write down the figures I read to you. Will you then memorise them and destroy the paper? It's vital that you do that. Memorise at once and destroy the paper. Anna, halloa! Are you still there?" "Yes, Stephen. Go ahead with your list. I have pencil and paper here." He proceeded to read out a list of figures. I had to ask him to speak up once or twice because of the crackling on the line, but I speedily got them on paper. They made no sense to me and I told him so. "All the better. Just memorise them. You're good at that, thanks to your stage training." Memory has always been my strong suit, and shortly after ringing off I had the list by heart and burned it. I reproduce it below for the benefit of the curious who may read these pages after I am dead, and be able to make more of it than I did at the time.

Length overall: 103 feet Now, every detail of that list is emblazoned on my mind, but a fortnight ago the only word that really meant anything to me was the name of Parsons. Before ringing off, Stephen stressed the need for secrecy. When he came home late that evening I chaffed him about it, for over the telephone he had been bellowing like a Thames bargee in a gale. "I know, Anna. The line was poor and you can hardly hear anyone on these things. I think the good old-fashioned telegraph is far superior, but I suppose one day we shall all be shouting down telephones. Luckily, everyone in the office is absolutely trustworthy: Chipchase, the senior clerk, the two lady typists, and young Marlow the junior. Tubby Winstanley had them all thoroughly assessed and they're perfectly sound and reliable." "Tubby's involved, is he? It's not another Difference Engine?" "No, I'm afraid poor Tubby got his fingers well and truly burned - and his moustache singed - with the Difference Engine scheme. After we were burgled he decided to take no further chances and that's why we have no written copies of those figures. This project will redeem him in the eyes of Whitehall, I hope. It's something that will really make the Jubilee celebrations go with a bang." "The way the Difference Engine did?" Stephen smiled ruefully. "Touché, Anna. I should have said it will astound the whole world. In fact, more than that." He turned up the newspaper's plan of the Naval Review. "What you've memorised is - no, I shan't tell you because you've made fun of it. Suffice to say that when we're aboard the Danube, you'll see the spectacle of a lifetime." I suspected that it was something to do with Mr Parsons and his yacht. The list I had memorised certainly seemed to be something to do with boats. Stephen was obviously so full of his little scheme that I thought it best not to reveal my suspicions, and contented myself with squeezing him tightly. He was much easier to squeeze than Mycroft had been, and where Mycroft frequently remained unresponsive to my little caresses, Stephen always returned them with interest, so that shortly afterwards we were in bed together. Stephen was becoming more expert in his love-making, and on that occasion we succeeded in reaching heights that until then I had experienced only with Mycroft. After it was over I lay panting and quivering in his arms. "It's the excitement of this project, isn't it?" I asked him, unsteadily teasing a finger along the line of his brow and round his ear. "It's the excitement of being in love with you," he replied, kissing me drowsily. I settled my arms contentedly about him. Only the stimulus of a case had ever been able to induce Mycroft to make love to me. Mycroft was an expert at the art, but sometimes we spent whole weeks - months, even - sleeping apart because he was bored with life. As I began to slip into a doze - Stephen was already asleep on top of me - it suddenly came to me that 1895 had been a very difficult year for Mycroft. Had the excitement of case after case, unusual for us, over-stimulated him? The Irish adventure, the ordeal I had gone through in Switzerland, the suicides, the dreadful business at Gowanburn Grange and the sequel at Grange-over-Sands had all piled rapidly one on top of the other. It was that year that Emmeline made advances to Mycroft and their affaire began. With that thought trickling to a standstill in my mind, I fell asleep. In the morning, Stephen paused before leaving for the office. "You haven't forgotten those figures, I trust?" Since only we were in the room, I rattled them off at him. "You are wonderful," he said, stooping and kissing me. "I must get away early. I shall be at the office all day, so don't wait for me. Go and do some shopping with Marie, or call on Joanna Winstanley, or whatever you please, my love. At least you'll know where I am." Marie and I did go shopping that morning. The streets were lively with visitors to the city, and what with the crowds and the temptation to stop and admire the decorations for the Jubilee, we had luncheon out and did not return till after two. As he had predicted, Stephen was very late home. When we went to bed, he forestalled me as I tried to climb onto him. "There is one thing we must discuss, my darling, before we - er - " "Oh, Stephen! We agreed that you would not bring your work into the bedroom, and this is work that you wish to discuss, isn't it?" "I'm afraid so, but it's very important. Anna, for the next few nights I'm afraid we shall have to sleep apart." "What on earth for?" "Because I shall have to lodge elsewhere. My darling, they fear in the Department that I am being watched. No, don't be afraid. I have men protecting me. In fact, there are two outside this building even now. But because I'm probably being watched, for a brief period I must move to lodgings." Memories of being watched by Colonel Moriarty set my heart racing. I slipped into his arms and nestled my head against his shoulder. "Oh, this is frightening. Who's watching you? Why? Sometimes I do so much hate this Government work of yours. It's becoming dangerous." Ten years earlier, with Mycroft, I'd have been eager for adventure. Now, however, at the thought that my loved one might be in danger, the tears flowed. He held me tightly. "No, darling, don't cry. I'm in no danger, nor are you. It's simply that someone knows about those figures I gave you over the telephone. Once the Jubilee Naval Review is over, I can return." "But the Review's ten days away, Stephen." "I know, but there's little we can do. Those figures are of absolute importance. You know them, and there is no copy. But we're certain that no-one knows you have them. If I vanish for a while, our adversaries will spend their time looking for me, so you see, I am to be a decoy." "What is so important about those figures?" "I can't tell you at present. But I shall take up lodgings in a safe house tomorrow night. You must remain here for the next ten days." I clung to him and buried my face in his shoulder, relishing the scent of him, the feel of him. I did not wish to be parted from this man for one night, let alone ten. "Why can't the figures simply be put into a safe somewhere?" "We dare not write them down. They're too secret - " "Stephen, you're trying to lie and you never can. Those figures could easily have been written down and secured somewhere. You are in danger. I must know about it." Once more I embraced him tightly. "You must not keep secrets from me." He returned my embrace. "Anna, how can I keep you in the dark? The figures are related to a secret enterprise - " "Don't tell me what that is, but tell me what the danger is." "The danger is that foreign agents may try to pursue me for the figures." "Yes, I understand that. But what if they pursue me too?" "We believe that they'll never think that a woman knows those figures." He lay silently for a while, as I lightly ran my fingers over his shoulders and chest, then worked my way down his torso until - "Ah! Anna, you've destroyed my train of thought." "Think of something else." I gently grasped with my hand. "This, for example. And - give me your hand - this. Yes. Oh yes! And - this." Losing control of myself, I sprang astride him. With a gasping laugh he settled me into position and joined me in the frantic rhythms of overpowering love. If we were to be parted, I wanted a night to remember. I was insatiable. Three times I took the lead and enjoyed him that night. "Stephen," I gasped, collapsing onto him as dawn was breaking. "I'm thirty-two and I want to have your children. I want us to marry." "Anna, my dearest darling. We shall marry, have no fear of that. And if you want a child, I shall do everything to assist you - at the right time." He began laughing, wildly kissing me at the same time. "I do so much love you," he said as we dropped into a refreshing sleep. That morning Roberts packed his master's bags and his own. I then truly understood that we were to be parted for almost a fortnight. Roberts was as discreet as my own Marie. He was a dark young man, fairly powerfully built, and if Marie had not already taken up with Watson, I could have imagined the two of them getting together. As Roberts took the bags downstairs to a waiting cab, Stephen kissed me and wiped my wet eyes with his handkerchief. "My darling, the time will fly. You need have no fears for me, nor for yourself. The street is being watched day and night by our own people. And Marie will look after you, as she always has done. Won't you, Marie?" "Of course, milord. Mam'selle Anna will be safe with me." As she spoke, my maid slipped her arm about me. It was a gross breach of propriety, but in our household there were greater breaches than that of a lady's maid taking a small, affectionate liberty. Stephen smiled approvingly, kissed me once more, and was gone. For a long time, Marie held me while I wept after the cab had driven away. Stephen had promised to write, sending the letters through a safe medium, and I was permitted to write back to a false name and address. To take my mind off my loneliness I chatted with Marie about her plans for the future. As I knew, she and Watson could not yet afford to marry and were hoping that his small practice would expand. That they already slept together when they could, I did not doubt, but I hoped that my faithful maid would stay with me until Stephen and I were in a position to make our liaison legal. Because I was preoccupied with thoughts of Stephen, I made the tactless blunder of offering Marie money to help their finances. For the only time in our long association she became angry with me. "Mam'selle, I know you mean well and I never fault your generosity, but if you make such an offer to me again I shall give notice. So there!" I was relieved when the doorbell rang and Tubby Winstanley puffed his way into the room followed by Mycroft. "Everythin' in order, Anna? Good. Holmes and I visitin' incognito, what?" I had to smile. Neither Tubby nor Mycroft could possibly remain incognito. Mycroft was immaculate in morning dress, with shining silk hat, lavender gloves, spats and cane. The faint soup stains on his waistcoat detracted from his appearance a little. Tubby had on his usual tweeds, which generally made him look like a country gentleman about to go ratting. Mycroft's bulk and Tubby's enormous waxed moustache made them as conspicuous in the streets as a pair of costermongers in the royal box at Covent Garden. They stayed for coffee and we chatted of various things, with Tubby doing most of the talking. As they took their leave, Tubby stopped. "Chin up, old girl. Been through worse than this. Remember Flame Natal, Ireland, Grüner, what? Look forward Naval Review ten days time. Got yer good berth on Danube. Grandstand view proceedin's. Stay overnight, what, you and Bywell, as I gather yer know. Holmes and I aboard Enchantress with Lords Admiralty and guests. Beefy, Joanna aboard Wildfire with Colonial premiers." "All this is to ensure no untoward incidents," added Mycroft. "Haven't forgotten Buffalo Bill's Wild West," said Tubby. "Trepoff affair - Deadwood Stage. Gad, ten years ago, what?" He squeezed my arm affectionately and left with Mycroft. I had noticed that Mycroft, never a talkative man, was rather more withdrawn than usual. He had had difficulty in meeting my gaze, and in my vanity I wondered whether he was feeling some pangs of remorse for his conduct over the past two years. It was a constant wonder to me that we still got on so well. To make up to Marie for my tactlessness I took her to lunch at the Langham and gradually, over the meal, we resumed the delicate subject of her future with Watson. "His practice slowly develops, mam'selle. But it is hard work, for John spent too long following Mr Sherlock on his cases and he still has very few patients." "I hope he succeeds, Marie. But has he thought of resuming his writing career?" "I have asked him that, and he says that Mr Sherlock expressly forbids him to write any new adventures, even though he has a whole tin trunk full of notes. I saw it once, mam'selle. 'John, my dear,' I said, 'if you had spent half the time practising medicine that you spent writing these notes you would be the most successful doctor in the kingdom.'" "Could he not turn his talents to writing something else? A column in The Lancet, perhaps, or why not do what his friend Dr Conan Doyle has done and write historical novels?" "I will speak to him, mam'selle." The following day brought the first of Stephen's letters. I read and re-read it, and spent a happy afternoon composing a reply, which Marie took out to post in accordance with strict instructions. She had to take a roundabout route to a pillar box by way of various shops, ensuring that she was not being followed. I knew I could trust her with the task, one which I made sure she had to perform every day. On the third or fourth day two letters came from Stephen. One was typed, but the address, salutation and signature were hand-written. "My dearest Anna, "Forgive the formal appearance of this letter. Please find enclosed two tickets for a concert at the Albert Hall tomorrow night. I suggest that you take Joanna Winstanley. At the concert you will be approached by one of the Major's agents, who will ask you for those figures I gave you some days ago. I hope you have not forgotten them! But I know that my darling Anna will not let me down in that matter. "Once you've passed them on to Winstanley's man, we shall let it be known that 'they' have missed their chance to find out the secret figures. Mycroft Holmes will follow you to the Albert Hall, although you will not see him. As no-one will suspect you of knowing anything, there is absolutely no danger for you. I would not otherwise ask you to go. "One thing I do ask, although it may seem rather strange. My next letter to you will not mention these tickets. Do not mention them in your letters to me. You will find out why in due course, and please burn this letter on receipt." After some deliberation I briefly explained things to Marie. "It will be the Major's doing, mam'selle; he will be up to something. He always has some plan up his sleeve, hasn't he?" By then I had examined the tickets. "These are dated for tonight." "Perhaps the letter has been delayed?" "You're right. Look at the postmark. It's a day late. It came with the one I was expecting today. This system they're using has its drawbacks. Marie, will you ring up Mrs Winstanley for me?" When Joanna answered it did not take long to persuade her to accompany me to the concert. She was keenly interested when we met that evening and I explained what had happened. "Henry loves this cloak and dagger work," she said as we took our seats in the Albert Hall. "And if it really is to do with a new boat, he'll be in his element. He adores anything to do with engines and mechanical things, as we know from that dreadful Difference Engine." The first half of the concert passed pleasantly, and as we reached the interval Joanna began to look about in some excitement. "If Mycroft followed us he certainly hasn't come in. I wonder who the mysterious gentleman will be." An attendant spoke at my elbow. I was wanted in the lobby. "Will you come?" I asked Joanna. "Just to make sure it's all right?" Joanna followed at a discreet distance as the theatre attendant directed me into the crowded lobby where a distinguished-looking man in evening dress greeted me. "Miss Weybridge? How very good of you to come to me. I should have come to you, but I thought it might make me conspicuous. Your friend, by the way, need have no fear. We shall not move from here." Instinctively, I looked for Joanna. She was standing a little distance away with her back partly turned towards us, studying her programme. Tubby's man was astute enough to have taken note of her. Odd that she should not have recognised him, but then the Secret Service did not generally make its agents known to one another. It had taken me years to realise that Joanna was an active agent. I had thought she merely tagged on to her husband's cases, as I did with Mycroft's. 4 "It's simply a question of repeating that list of figures which Lord Bywell passed on to you. I'll scribble them down on the back of my programme. Ready? Fire away, then. Don't worry about being overheard. A lively crowd always makes good cover." Dutifully, I repeated the list. He nodded at each set of figures and noted them rapidly with a silver pencil. At length he pocketed his programme. "Splendid, Miss Weybridge. You see, we had to destroy all copies of those figures in order to keep them truly secret. We could take no chances of anyone seeing them, and so for the past few days you've been the only person who knew them by heart." "I don't know them. They mean nothing to me except what I can guess. I realise it's something about boats, but I know nothing about boats." "All the better. You could have given away little under torture." He bowed and withdrew, while I stared after him with open mouth. Joanna came up to me. "Seems to have been quite painless. Why, Anna, what is the matter with you?" The stranger's parting words had left me in a kind of paralysis. Tortured? By whom, for God's sake? The figures I'd been asked to memorise were only something to do with a boat, after all. "We'd best get you home," was Joanna's reaction when I repeated to her what the man had said. "Henry would never consider torture, but I can think of those who would." "Do you mean I'm in danger?" "I think that, after all, this business may have had nothing to do with Henry, or Lord Bywell. Come, let's miss the second half and find a cab. I had my suspicions from the first, Anna. Just as well I decided to wear this." We had made our way to the exit, and Joanna moved aside a silver locket she was wearing. Beneath it a small bright object gleamed through a button hole in her blouse. "A detective camera. Ever heard of them?" I nodded. Mycroft had one. You wore it round your neck with the tiny lens showing through a button hole and, with a small cable, you could take photographs unobserved. 5 "I got a few snapshots of him. I hope they come out." Stephen returned early next morning, for Tubby, who indeed had known nothing of the evening's events, summoned him, and the two hurried to the flat. The morning sun of midsummer streamed through the sitting room windows, striking a bright square across Tubby's bald head as he stood with his back to a roaring fire with a Japanese screen keeping the heat from the rest of us. His brother Richard, or Beefy, as we called him, stretched a languid arm and took up a photograph from the table. He took it to the open window, where Joanna had already retreated from the heat. On the sofa Stephen sat pale-faced and haggard. I was beside him with my arm about him. "I sent you no typewritten letter," said Stephen. "The writer told you to destroy it?" "Evidence gone," said Tubby. "Yet Anna convinced handwritten signature and greetin' yours, Lord Bywell. Good forgery, what, Anna? Now, these photos. Chipchase, without doubt." "Chipchase is your senior clerk, isn't he?" Joanna asked of Stephen. Stephen nodded dumbly. "Can't understand!" said Tubby. "Checked him meself. Background impeccable. Right school, right connections etc. Yet goes and does this. Reminds me of Fitz-Forsythe. Can we trust anyone these days?" "Where is he now?" asked Beefy. "God knows. Depends on whom workin' for." "A Certain Foreign Power, you mean?" smiled Beefy grimly. "Think our old friend Fritz is in this?" "Von Tarden? Will investigate." Tubby took out his huge meerschaum pipe and rapidly crammed it with the vilest tobacco that had my eyes streaming in minutes. Poor Stephen never moved. He sat in complete despair, his shoulders sagging, his head down. I hugged him tighter and whispered, "Don't worry, dear. It's not your fault." He had already offered his resignation by telephone, but Lord Salisbury had refused to accept it. "One bright spot," mumbled Tubby through his pipe, after a few minutes during which Joanna and I frantically wielded fans in the thick of the pungent blue smoke. "Holmes on case." He sucked hard on the disgusting gurgling meerschaum. "Spoke to him Diogenes last night. Followed me out and took cab direction Whitehall. Obviously keen get straight onto case, what?" Or straight onto Lady Bywell, I thought, holding Stephen tighter. She still lived at Richmond, and Mycroft had almost certainly been heading for a train to take him there. Having taken up the case, he would need to gratify his animal desires with his new mistress, as he had often done with me. I wondered what sort of night he had given Emmeline, whose own skill at the amorous arts was not high, as I gathered from hints that Stephen had inadvertently dropped. Perhaps she was learning from Mycroft, just as I had. The doorbell rang and a heavy tread came up the stairs. Tubby, scraping out his pipe into the fire with a small silver knife, looked up like a foxhound hearing the horn. "By Gad! By Gad! Could it be?" It was. Marie showed in "Mr Holmes". As Mycroft entered, Stephen looked up with hope in his glance, and Tubby fairly bounced to his feet. I slipped my arm from round Stephen's waist and sat demurely with knees together and hands on my lap. "Progress?" said Tubby, as Mycroft handed hat, cane and gloves to Marie. "Some. It appears that Lord Bywell's office contained an agent of von Tarden's, as you will have already inferred. When his lordship telephoned Anna," he continued, sinking heavily into an armchair, "the only clerk in the office was Mr Everard Chipchase, or, to give him his real name, Nikolai Sergeivitch Skriabin." "What!" exclaimed Stephen. "A Russian," Mycroft nodded. "But not, I think, in the pay of the Tsar's government. He appears to be a freelance, working for whomsoever pays him most, and at present that would appear to be Berlin." "Good Gad!" Tubby sat down and automatically filled his pipe again, the whole time keeping his popping eyes fixed on Mycroft. "But - but - impeccable record, what? Perfect English, Oxford drawl, everythin' - everythin' - " "Everything the modern English gentleman can offer, Henry?" Joanna was smiling and shaking her head. "Anna and I met him last night, Mycroft. He certainly fooled us all." "Except you, Joanna." Mycroft had taken up the photographs. "Yes," I said. "What made you suspect him, Joanna?" "The typewritten letter. Can you type, my lord?" "Never learned," said Stephen. "I thought not. And the letter would therefore have been typed by a third party. Why should Lord Bywell order that, if he wished to preserve secrecy? Why not simply write it by hand? You see, although the writer could forge Lord Bywell's signature and a few written words, he didn't trust himself to keep up the deception over a page of writing." Mycroft nodded. "Excellent reasoning, my dear Joanna." He tapped the photograph with a fingernail. "This fellow Skriabin, or Chipchase. When the telephone call was made, he was working at a filing cabinet near the door of Lord Bywell's office, which was slightly ajar." "That would be part of his duties," said Stephen. "He handles the most confidential material himself, which is kept in that filing cabinet." "Including the figures you read out to Anna?" "No. They were so secret that only I had them. Even the Major here didn't know them." Mycroft looked momentarily puzzled. "Secret, you say? Yet - no. No matter. To return to the intriguing behaviour of Mr Chipchase. In the office were the two lady typists, working at their machines. One of them, Miss Edna Fairbanks, thought the behaviour of Mr Chipchase to be rather unusual, in that he dropped sheets of paper near the door, and had to stoop for them. She noticed that he fumbled with them before returning to the cabinet. He did this twice, then seemed to become aware that Miss Fairbanks was watching him." "He was listening, of course," I said. "It was a poor line and I had to shout once or twice," said Stephen. "I suppose that gave away the figures to him." "Correct. But he could not hear all he wanted to because of the noise of the typewriters. He could not ask the two young ladies to cease typing without further arousing their suspicions. Therefore his ruse to speak to Anna at a time and place when he knew Lord Bywell would be away, and the pretence of being from Major Winstanley." "Damned cheek!" muttered Tubby. Cheek indeed, but there was nothing that any of us could do. Mr Chipchase, or Skriabin, had outwitted Tubby, Stephen and the entire Government department. Skriabin vanished, and as copies of Mr Parsons's figures were readily available from me, Tubby shrugged his shoulders and said that was that. The great thing was that Stephen no longer needed to live away from me. The night of his return was one of the most memorable we had spent together. He was hungry for me, as I was for him, and we made love until the short summer night was over. In the days following, Stephen threw himself into the preparations for the Naval Review, Mycroft went about his Government business, and Marie and I frantically prepared for our stay aboard ship as guests of the Royal Navy. It was worse than rehearsing a new play, I decided, as the day neared and not more than half my outfits were ready. The last thing I wanted was to let Stephen down in any way, so the indomitable Marie almost wore herself out chivvying dressmakers, milliners, bootmakers and haberdashers. I rewarded her with a new outfit for herself, which spurred her on to even greater efforts. Thanks to her, when the day came we were both fully equipped for our jaunt. It was as well that neither of us had the slightest inkling of what was to befall.

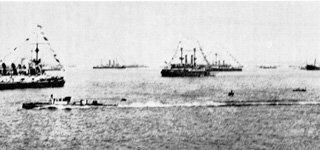

Saturday June 26th "What pretty flags!" I exclaimed to Stephen. "How well they decorate their boats." "Ships, darling, is what they prefer to call them. And the pretty flags are signal flags, not decoration. Each has its meaning. That striking white, blue and white one, for example, if hoisted on its own, means 'I am on fire and you should keep your distance'. In that string of flags, however, I don't know what part it plays." We were standing on the quay at Portsmouth, surveying the fleet which occupied the whole of the Spithead anchorage. From one horizon to the other we could see nothing but battleships, with the prettiest flags that ever I saw fluttering from lines stretched between their masts and flagpoles. 6 In the background of our picture lay the Isle of Wight, quite heavenly in the warm June sunshine. "Well, my love," said Stephen. "There's our tender. Let's get aboard for the Danube." He led the way to a rowing boat into which some important-looking people were clambering from a flight of steps. All the ladies were dressed as I was, in summer costume, with light hats and gauzy veils. With my brand new outfit I had my new lemon-yellow parasol and gloves, but I wore my older boots, because Stephen said that the salt would discolour them. I felt pleased with myself, for I was as smart as any other woman present. Our baggage was in the care of Roberts and Marie, who had already crossed by boat to our ship, where we were to spend a day or two aboard. Earlier, I had noticed how Marie fended off the attentions of a sailor. Before she took up with Watson, she would have flirted with the seamen; now her behaviour, like her dressing, was impeccable. Stephen helped me into our gently rocking boat, where we took our seats among a brilliant party of members of the House of Lords and their ladies, only some of whom, I suspected, were wives. In fact, I recognised a young theatrical acquaintance on the arm of an elderly peer, and we exchanged silent giggles across the crowded boat. "She used to be the mistress of Sir Percival Blakeney," I whispered to Stephen as the sailors began to row us out. "He was distraught when she left him." "Look, Anna," said Stephen. "That slim little steam yacht over there is Mr Parsons's Turbinia. Isn't she sleek? And there's Holmes in a tender. He's to be berthed aboard the Enchantress with the Major." As we pulled smartly up to the bottom of an enormously long flight of steeply-angled steps at the ship's side, the boat carrying Mycroft passed on. I spent the next few minutes concentrating on safely climbing what Stephen called the accommodation ladder while worrying about how much stockinged calf I was displaying to some of the gin-soaked old bounders leering up from the boat below. We were shown our cabins, temporary structures, I later learned, run up by the ship's carpenters to give us comfort and privacy. They were remarkably snug and well-appointed, and I marvelled at the skill that had gone into their construction. There were not many other guests sleeping aboard. Marie was accommodated with another lady's maid on a lower deck, while Roberts shared a cabin with two other valets. Unfortunately my cabin was on the deck below Stephen's, and I suspected that the arrangement was deliberate. Someone, probably Tubby Winstanley, had decided not to risk scandal by lodging us together. "The gentlemen should all have come up first, mam'selle," said Marie as she unpacked my things in my cabin. "They should have known it is against propriety for a lady to go up a steep ladder ahead of the men. In our boat, we lady's maids insisted that the gentlemen's gentlemen went up before we set foot on the ladder. And we made the sailors look the other way." "Really, Marie, you are becoming so proper that I can hardly keep up with your example." "I should not like John to think I had shown myself up in front of the valets, mam'selle. And do you know? Not once did I feel sick. But goodness! The high thresholds into the passageways on this ship! Twice I almost fell full length over these things. The sailors tell me they are called storm steps and are meant to keep out the rough seas. The sea sometimes comes into the ship, mam'selle! Think of that! And I thought crossing la Manche was bad. And Mr and Mrs Winstanley are aboard, mam'selle. I am lodging with my friend Elisabeth, their maid. They are berthed on the same deck as Lord Bywell." "How strange! I thought that they were to be on the Wildfire." "Do you wish to visit them, mam'selle? I know the way." Invaluable Marie! She led me along the confusing passageways, all echoing grey-painted steel and permeated with the smell of paint, tar, coal and what I suppose was engine grease. The ship was thronged with day-visitors as well as seamen, and it was with difficulty that we squeezed through the bustle to a cabin door, where Marie knocked and Joanna welcomed me. As she opened the door, a thick blue fug of smoke billowed out. "Henry's here," said Joanna. "He and Richard are chuckling away with Lord Bywell over something Mr Parsons has planned. Of course, being a mere woman, I'm not to know anything about it." "But I thought Henry was on another ship with Mycroft." "There's been some change of plan. Anna, why don't you and I take a stroll on deck?" As I was unsure of finding my way back to my own cabin, I made Marie accompany us, since she seemed to know her way about. At first, however, I thought she had gone astray, since she took us down into the dimly lighted depths of the ship. "This is the quickest way, mesdames. One of the sailors showed me. We go down this ladder." We laughed and shrieked as we negotiated the steep steel ladder backwards, Marie giving us an arm at the last rung or two. We found ourselves in a deserted passageway where the throb of distant machinery came to our ears, the air was very warm, and we could feel a continual gentle vibration underfoot. The smell of oil, paint and tar intensified. It was not unpleasant, but there was something decidedly masculine about it, and we felt greatly daring to be penetrating the depths of this strange new world. Throughout our tour, Joanna talked. She told me that Tubby had changed the accommodation plans at the last minute and was himself berthed next to them. "The Wildfire was such a comfortable ship, far superior to this one. Of course, Henry has told me nothing, and Richard simply nods and looks mysterious if I ask him why we had to move. And why has Henry moved himself, I wonder? After all, this ship is reserved for members of the Lords. Here's another of those dreadful storm steps, Anna. How ridiculous to have such things on a boat! I'll bark my shins, I know I shall, if I'm not overcome first by this awful stuffiness." "Along this passageway, mesdames, if you please, and past these strange cupboards." "I'm amazed at how you find your way about, Marie, and we're not having to push through crowds of other visitors. Oh, this must be where they store their spare uniforms," for Joanna had a tall locker open. "Look, Anna. Couldn't you wish to die for one of these smart navy blue outfits?" "It is to the right at this corner, mesdames," said Marie, leading us past a cabin, through the open door of which came a pungent smell which cut startlingly through the odours of the ship. "Ugh!" said Joanna. "Chloroform, surely." She peeped through the door, but I hung back. Chloroform always made me shiver now. "Deserted. Medical stores, I think, Anna. Where next, Marie?" Marie took us up one more ladder, and the odours of tar, paint and grease gave way to the smell of the sea and a refreshing gentle breeze which carried the salt to one's tongue. Carefully negotiating another storm step, we found ourselves on the sunny deck. "Where are we?" "This is the deck for the sailors, madame. We must go up here to reach the visitors' deck." She led the way to another ladder, only to step back, baffled. "This chain across the steps was not there before. We are not permitted to go this way now, I think. But there must be another way. Please stay here, mesdames, while I enquire." As Marie was about to go off in search of someone, a party of sailors appeared from a doorway. One of them unhooked the chain and most politely showed the three of us up to the visitors' deck. "What's about to happen?" asked Joanna, for the sailor's companions were bustling energetically about some kind of crane or lifting apparatus, swinging it out over the side and attaching a large cradle or chair to it. "Very important party coming aboard, ma'am. If you stay here you'll see him, if the bosun's chair don't give way under him, that is." With a grin and a touch of his cap he left us and joined his fellows round the crane. They lowered the chair out of sight over the side but, although Joanna and I stretched over the rail, we could see nothing. There was a boat alongside, we gathered, but no-one in it could we see. The sailors began to turn a handle on their crane and the rope tightened. More men joined in and then there was a sudden flurry of movement at the handle, with one or two more men seizing hold of it. There were sudden exclamations from both the sailors at the crane and those in the boat below. "My Gawd, 'e's gone in!" cried the sailor who had spoken to us. He glanced up at me and winked. "Told yer, ladies, didn't I?" We leant so far out that we were in danger of falling overboard. Even Marie, who in public normally preserved the decorum expected of a lady's maid, leant over the ship's side. Eventually the gang at the crane heaved away again and slowly something came into view. It was a huge, dripping mass of a man in what the sailor called the bosun's chair. "I should have known," sighed Joanna. "Oh, Mycroft!" I groaned. The sailors set Mycroft down on deck and helped him out of his unsteady seat. He was wringing wet, his suit completely ruined. Strangely, his silk hat was still on his head and his hand still gripped his cane, but the shapeless form that stood below us was a parody of the immaculate figure I was used to seeing. "How those men are keeping their faces straight I don't know," said Joanna, but as Mycroft looked wrathfully about him it was clear that anyone who even met his gaze would suffer for it. An officer hurried forward and helped him below decks, whereupon the sailors collapsed, clinging onto the machinery or one another. "What is he doing here in any case?" I wondered. As I spoke a hail from the boat alongside caused the sailors to lower their rope again, this time with a large hook attached to it, which brought up Mycroft's trunk. He was coming aboard to stay. "There's something afoot!" exclaimed Joanna, and led the way below decks. Joanna and I were ensconced in the Winstanleys' cabin with Beefy and Tubby long before Mycroft made an appearance. He was once more immaculate, in a light summer suit, a Panama hat with a colourful band, and a jaunty necktie. "Hear yer had unfortunate accident, old man," said Tubby blandly. Mycroft glared at him. "It would not have occurred, Major, had the Navy been better equipped. I shall probably go down with cold after this." "Not if you take the advice I gave you, Mycroft," said a new voice, and a middle-sized, square-jawed man with a moustache came into view. "Dr Watson!" I exclaimed. "What on earth - ?" Watson shook my hand and Joanna's, bowed to Tubby, and ensconced himself beside Beefy. "I'm here as Holmes's representative - Sherlock, I mean. He was unable to come, and insisted that I did. I followed Mycroft aboard, after his luggage, that is." Before I could ask why Sherlock Holmes should have been present at all, Joanna spoke. "Are you staying on this ship now, Mycroft?" Mycroft bowed. "Events have taken such a turn that I felt I should serve a better purpose if I could immediately call on your husband and the Major here. I brought Watson aboard as a useful accessory since Sherlock cannot attend." "Events?" said Beefy, while Tubby leaned forward, refilling his pipe. Mycroft took out his snuffbox filled with his favourite lung-searing brand. I could smell the sharp tang of it at six feet. In moments both Joanna and I were dabbing our eyes with handkerchiefs and wielding our fans. Mycroft took no notice, and Tubby stoked up his pipe and began to emit a thick cloud of blue smoke as he sat on the bed and squinted sideways and upwards at Mycroft. "Something up, Holmes, what?" "Merely a prize piece of audacity, Major. The theft of the Turbinia here at the Review." "Gad! Who's done that?" "No-one yet, but it is planned. Anna, my dear, I see that Marie is stationed outside the cabin. Would you mind sending for Lord Bywell?" Mycroft settled himself into a small folding chair which creaked dangerously beneath him as his ample shape spread over the flimsy structure. Stephen entered and shook hands with him and Watson. "The fact that you're here, Holmes, means trouble somewhere." "Precisely so, my lord, and the fact that I asked you to be good enough to join us should suggest where the trouble is expected." Stephen instinctively looked at me. Tubby chuckled. "No, Anna's done nothing, my lord. But someone about to, accordin' Holmes." Mycroft steepled his fingers and looked at each of us in turn. "After the affair of Mr Chipchase alias Skriabin, I made careful enquiries, enlisting the aid of Sherlock. We called on Skriabin's former lodgings and found that he visited Newcastle upon Tyne some weeks ago." "He did," said Stephen. "I remember him asking for time off to visit a dying aunt up there." "How long was he away from the office, my lord?" "About four days. He returned on the Monday, I remember, wearing a black armband and asking for a further two days to attend the funeral." "Days which you granted him?" "I did." "There was no dying aunt, of course. What he was doing was trying to get hold of the plans of the Turbinia, particularly data on her engine. A wire to Mr Parsons's works cleared up the point that a stranger calling himself Hargreaves but answering to the description of Skriabin roused some suspicions among Parsons and his management. They thought that he was something to do with a rival firm and sent him packing." The chair groaned as Mycroft leaned forward and fixed his gaze on Tubby. "The next thing we found, Sherlock and I, was that Skriabin has been in touch with our old friend from Berlin." "Von Tarden!" exclaimed Tubby. "How'd yer find that out, Holmes?" Mycroft smiled. "His landlady noticed the foreign cablegrams and letters. There were several, and she had even managed to retrieve one of the envelopes with a Berlin postmark. Official enquiries to the Hauptpostamt in Berlin revealed the sender of those cables." "You said," interjected Beefy, "that Skriabin intends to steal the Turbinia here. What do you know of that?" "Not much. My ship, the Enchantress, was berthed not too far from the Turbinia. From Enchantress I observed the Turbinia closely through my glasses. I saw Parsons and his guests go aboard. Then something strange happened. A rowing boat took off some of the Turbinia's crew, who were replaced by a number of large, bearded men. And among them was a man who looked uncannily like our friend Fritz. Mind you, I was watching from some distance. But the large men went below and neither Parsons nor his guests made a reappearance." Tubby pulled out his watch. "Still about an hour before the - er - display. Nothin' planned before Royal Yacht appears. Any chance von T makin' move before then?" Mycroft shook his head. "It would arouse suspicion among those who know of Parsons's plan. You know about it, of course, my lord." "Yes," replied Stephen. "And I think I see your drift, Holmes. If Chipchase -Skriabin, that is - found out about it, then of course the whole scheme to steal the yacht would have the perfect cover of Parsons's planned exhibition." I was afire with curiosity about this exhibition or display, but dared not interrupt. "Where do you think they'll take the Turbinia?" asked Beefy. "Kiel," said Joanna unexpectedly. "I always said to you, Henry, that we should never have given up Heligoland. And I do wish you'd let that pipe go out." 7 Mycroft nodded. "And I can tell you when and how they will make their bid for the yacht. As for the pipe, ladies, would you mind leaving us?" He attempted to rise from his chair but it suddenly collapsed beneath him. In the confusion Tubby politely opened the cabin door and ushered us out in a cloud of his pipe smoke. We were both too astounded to utter a murmur. Joanna's expression, I am sure, merely reflected my own astonishment and anger at being thrust out as though we were not to be trusted. In something of a daze I went down the nearest stairway, Joanna following with Marie, who had waited outside all the time. It took us some time to find our way to the deck, for in my temper I had led the way down the wrong ladder. At length we emerged onto the deck below the one reserved for visitors. "I could have swung for Mycroft!" said Joanna between her teeth as she gracefully negotiated the storm step. "That chair breaking under him served him right." I barked my shin on the step, and uttered some very unladylike language. "Practically throwing us out of the cabin," went on my friend, unmoved by my outburst. "Let's look at that leg, Anna. There aren't any sailors about, I hope?" I drew up my skirt and examined my leg. A nasty bruise was starting under my stocking. "At least it isn't bleeding," said Joanna. "Marie, would you go back to the cabin and - but no, Mycroft simply wouldn't let you in." "I can get something from the medical cabin, madame. It is just below this deck. A bandage and a cold compress, perhaps, will treat the bruise." Marie and I went below decks again and cautiously entered the stuffy little cabin that reeked of chloroform and medicines. The only light was from a little window giving onto the passageway where there were lamps, but Marie found a locker containing bandages and set to work on my leg. Joanna, meanwhile, had remained on deck, but she appeared in the doorway as Marie finished and was putting away the bandages. "Come upstairs and look at this!" We hurried up the ladder into the fresh air again. Joanna pointed down the line of ships. A small rowing boat containing five figures was slowly proceeding between the distant vessels. My heart sank. "Good heavens!" went on my friend, going to the rail. "It's practically sinking under them. Oh, I do hope they don't do anything foolish." "I think they already have," I replied, my voice trembling as I joined her. What was the man I loved about to do? "Mam'selle, do you think they will sink? Can they swim?" "They're so - so muddle-headed," declared Joanna. "Why didn't they simply warn the captain and ask for help? A boatload of armed sailors or Marines would soon put paid to these foreigners." "I suppose they want to keep it quiet," I said. My mind was racing to comprehend what was happening. Surely they were not heading for the Turbinia? Joanna breathed hard through her nose and drummed on the rail with her fingers, staring the while at the distant Turbinia while the small boat, with Mycroft bulking large in his seat, crawled further away from us. "There's smoke coming from the Turbinia's chimney," Joanna suddenly said. "Oh, if only we had - " She broke off and hurried over to a couple of young officers, cadets or something of the sort, who had emerged from a door. After a moment's talk, one of the boys unslung his binoculars and handed them to my friend. "Thank you so much," she said. "I shall return them very shortly." The two boys smiled shyly and sauntered off to the other side of the deck. Joanna returned to us and trained the glasses on the Turbinia. "They're getting closer," she said. "Take a look, Anna." The glasses showed the Turbinia lying apparently deserted, except for the thin column of brown smoke rising from the wide chimney. Mycroft's boat stood dark against the light sides of the steam yacht. "Does the smoke mean that they're going to move off, do you think?" asked Joanna. "Excuse me, madame," ventured Marie, "but is that ship over there not the Royal Yacht? Surely we will soon be moving off behind her?" 8 She pointed at the distinctive shape of the Victoria and Albert as, following another ship, she steamed through the lines of warships, a stately old lady of a bygone age promenading past the up and coming generation. The Royal Standard fluttered at the masthead but, as I trained the glasses on her, I could see no sign of the portly figure of the Prince of Wales, representing the Queen that day. I turned to the Turbinia and scanned her decks. The column of smoke was thicker and rising faster. Were they getting steam up? Mycroft's boat had drawn almost alongside. "The damned fools must be going aboard," said Joanna. A bell clanged somewhere on our ship and the two cadets hurried over to us, retrieved the binoculars, and rushed off. "We're going to move, Anna. What can we do?" She strained anxiously against the rail. I could guess her fears for her husband, and Marie's for Watson, for my own thoughts made me cling to the rail for support. "Anna, you're as white as these decks. Look, I'm going to the Turbinia." "I'm coming with you." Already Joanna was heading below decks, negotiating the steep ladder with easy grace. I followed. Marie, without a word, plunged after me. We caught up with Joanna in the deserted passageway near the uniform lockers. I had no idea how we were to reach the Turbinia, but Joanna clearly had some plan in mind. "Have you your pistol, Anna? No? What about you, Marie? Is that your little derringer? But with only two rounds? And hardly any stopping power, even if you used it, Anna. But we must try - " "What - ?" I began, but my friend wrenched open the door of one of the lockers. Far off, another bell clanged and a deep throbbing began to quiver through the ship. "This will fit me. And I think this will fit you, Anna. Marie? You need not come with us if you don't wish to." As she spoke, she hastily removed her short jacket and flung on a sailor's blue tunic. "I will come, madame. No, Mam'selle Anna, don't try to stop me." Marie took a suitable uniform and began to get into it, while I followed suit. The wide trousers went on easily under our skirts, which we discarded together with our petticoats. The tunics replaced our fashionable jackets, and our hair was gathered up under the caps. We had perforce to keep our own boots on, and as our own clothing went into the lockers, Marie began to laugh uncontrollably as she rolled up the trousers to fit her. "Mam'selle, what will the sailors say when they find our dresses? We are setting a new fashion. Do I make a handsome sailor?" "Bring your pistol, Marie," said Joanna, transferring something from the pocket of her dress to her tunic. "And don't lose your nerve. Be as you were in Switzerland. Can you swim?" "Swim? Why, madame, are we to swim there?" "No, but we may have to swim away." "I - can swim, madame." The grim-faced Joanna led us back to the deck. "Now, we need a small rowing boat. Should be plenty of those about. But first, some flags." From her pocket she produced her case of nail scissors. Reaching up to snip off a line of four or five small flags from the bunting, she stuffed them into her pocket. "For signalling. I know some of the semaphore signals, such as 'help'. Come on. This way." It was amazing how easily we went into this mad escapade. Down a ladder we scrambled to a large rowing boat, which had a small one tied behind it. We clambered across into the small boat. Joanna intended to support her husband, and I intended the same on Stephen's behalf, while I had no need to question Marie's motives. Marie and I took an oar each and we cast off. Up to then, to my astonishment, no-one had questioned us or even paid attention to us. And I don't believe that for one moment we even looked like sailors. As we rowed off a gang of real sailors swarmed down the ladder to the large rowing boat, untied it, and began to row away from the Danube. One of them shouted something at us and we pulled harder at our oars. The officer in the large boat shouted something again, in an angry tone, but at that moment the deep siren of the Danube sounded, booming over the water and making the three of us jump. The sailors in the Danube's rowing boat swept their oars into the water and pulled hard away from the ship and away from us. "She's going to move off," said Joanna, sitting in the back. "My God! What if she runs us down?" Marie and I simply pulled. We were not good at rowing, since neither of us had done it before, and it was an erratic, splashing progress that we made away from the Danube. Luckily, the sailors in the other boat were fully occupied with getting out of the way of their own ship to pay us any further attention. Joanna craned forward and her face turned white. "Oh, my God!" "What?" "There." A small rowing boat was floating empty near the Turbinia. "That's their boat, I'm sure of it, Anna. What's happened? Oh God! There's Mycroft's hat in the water!" My mouth was dry and for a few seconds a cold wash of fear flooded through me. Then I began to pull again, Marie keeping up with my strokes as we splashed and rocked our ungainly way onward.

RICHARD WINSTANLEY TAKES UP THE NARRATIVE (added July 4th 1897) Miss Anna Weybridge is a very persuasive young lady. I've seen her account of our little escapade. I gather she wrote it up last week, and now she wants my part of the story. At first I refused to add anything at all. The Department doesn't want anything in writing about what happened, especially now that our version has been accepted by the public at large. In fact, when it was all over and done with, von Tarden himself offered me his hand with no hard feelings. I took it, for he's a sporting type, is Fritz, and I know he'll keep mum. It's in his interest to do so. But Anna pestered me and swore that she wouldn't publish and the secret was safe with her, and her maid was equally reliable, and so on, all of which I knew, of course. On top of that, she fluttered her eyelashes at me and gave one of those smiles of hers that really should be restricted by licence to about two a year. The effect they have on a chap! However, to get to the point, about the part Holmes and everyone played in things, and how it all went and so forth, well, there's no need for me to describe it, for Anna has done that. Once we got to the delicate part of planning how to stop Fritz and his chums, Holmes and Tubby politely but firmly showed the ladies the door, or rather, Tubby showed them out as Holmes' chair collapsed. Jo and Anna looked as if they could have strangled them, and I must say it was rather tactless, sending them out as if they couldn't be trusted. After our adventures in Switzerland, Northumberland and Furness I knew we could trust all three of them. Once we were alone, Holmes clambered from the wreckage of his chair and faced us gravely. "Gentlemen, as some aboard this ship are aware, Mr Parsons intends to run the Turbinia at top speed through the lines of the fleet, after the procession of ships led by the Royal Yacht has passed through." Tubby and Lord Bywell nodded. "Unauthorised run at thirty-five knots, what?" said my brother. I knew about this plan of Parsons's, but I wasn't too keen on the way he meant to divert attention to himself on a great day dedicated to Her Majesty. "It will be a spectacular display of the boat's speed and power and will convince even the most conservative and hidebound members of the Admiralty that Mr Parsons's turbine engine should be taken up by the Royal Navy," said Holmes. Tubby shook his head. "Thought you knew nothin' of this, Holmes, but should have known better. Impossible keep secrets from you." He frowned. "Didn't get information from Anna Weybridge, by any chance?" "Certainly not, Major. If Anna knows anything of the Turbinia she has kept it to herself." The thought that Anna might know anything about this boat took me aback. How that woman gets herself into things I simply can't imagine. Holmes took a pinch of snuff and went on. "The Chipchase affair first drew my attention to the boat, of course, and although you seem to have thought its new type of engine to be a secret, I can assure you that in the North it is well known. Not two months ago the Newcastle Daily Chronicle described the Turbinia as 'the fastest vessel afloat'." 9 Holmes gave a mighty sneeze and continued. "I imagine that the finer details of the boat were not generally known, since Skriabin - 'Chipchase' - went to so much trouble to get them. What they do not know are the measurements of the turbine blades, information essential to an understanding of the engine." "Our ship, the Danube, will be in the Royal procession, won't she?" I asked. Tubby nodded. "In that case we'll have a good vantage point," I continued. "Perhaps we could get vedette boats after the Turbinia?" Holmes shook his head. "At over thirty-four knots, Winstanley? Nothing can catch her. Even if we try to block her path, she could steer past any such attempts and get clear away under von Tarden's direction." "Audacious beggar! Typical von Tarden scheme. Bold, unexpected, good chance of success." Tubby scratched his cheek with the stem of his pipe, then suddenly stood up. "Another thing. We'll be movin'. Can't do much if we're trapped aboard this ship. " He pulled out his watch again. "Gad! Less than half an hour to procession. No time inform Admiralty. Take matters into own hands, what? Beefy? Watson, Holmes, you game? My lord?" Lord Bywell, Dr Watson, Holmes and I agreed. Action was what we needed, and I felt the old heart begin to pick up speed as we rapidly made our plans. "We must decide on some way of boarding the Turbinia without creating a scene," said Holmes. "Gad, yes!" agreed Tubby. "Secrecy of absolute essence, what? Success by von Tarden makes us laughin'-stocks Europe, war inevitable, not good idea at present." "Should we not go and reconnoitre the Turbinia?" continued Holmes. "We must if necessary board her ourselves. Are you armed?" We were. I had my revolver, Holmes had his, and Tubby brought a stout Penang lawyer from his cabin as we went on deck, while Bywell fetched a loaded malacca cane. Watson had his cane with him. Tubby was still smoking furiously like one of Her Majesty's ships. Anna and Jo had disappeared, having obviously taken umbrage, and the maid was nowhere to be seen. The five of us were undisturbed as we surveyed the scene from the rail with Holmes's fieldglasses. The whole of Spithead was packed with lines of anchored warships, smaller steam vessels among them weaving spidery webs of dark brown smoke against the sunny sky and leaving gleaming white trails in the blue-green, sparkling water. The smaller craft were dwarfed by the huge fourteen thousand tonners towering their buff-coloured funnels and white superstructures over them. These black-hulled monsters were battleships like the Royal Sovereign and the Majestic, which could thunder along at seventeen knots - that's about twenty miles an hour. In another line we could see a number of foreign vessels of all kinds, including the König Wilhelm. Aboard her, we knew, was Prince Henry of Prussia, representing the Kaiser. Even the foreigners had dressed their vessels from stem to stern with bunting, which had drawn much appreciative comment from Jo and Anna. But it was the small, low-lying shape of the steam yacht Turbinia which held my attention when Holmes pointed her out to me. Even through the glasses we could see no activity. I noted her lines, long and lean. No more than nine feet wide, Holmes said, but over a hundred long, she was powered by an innovative engine which could rip her through the water at over thirty-four knots, twice the speed of the huge battleships. "You can imagine why foreign powers would be interested in the Turbinia," said Holmes. "I certainly can," I replied. "A ship with engines like that could appear from nowhere and sink one of these battleships with merely a couple of well-aimed torpedoes." "Quite right," nodded Tubby. "Serious threat capital ships, exceeded only by submarine. But submarine still to come. Turbine engined vessel with us now. And must remain with us, what?" I had the glasses to my eyes, and, as Tubby was speaking, I noticed a thin wisp of smoke starting to rise from the wide funnel. "We must lose no time," said Holmes urgently. "There's a tender still moored at the foot of the boarding ladders beneath us." "Too big for the five of us," grunted Tubby. "The only other one is that skiff beside it," said Holmes. "Bit small, don't yer think?" asked Tubby. "What choice have we?" replied Holmes. He began clumsily to descend the accommodation ladder, which was actually a flight of steps. I doubt whether he could have managed a real ladder. Tubby, Watson, Lord Bywell and I followed and, after much puffing, scrambling and stumbling, accompanied by some inventive profanity, Holmes and my brother reached the bottom and climbed across the large cutter with Watson, Bywell and me behind. We clambered into the small skiff, which settled fearfully low under the combined weight of Holmes and Tubby. I insisted on rowing, with Bywell in the bow, Holmes and Watson amidships and Tubby in the stern. We were so low in the water that I had to proceed with the greatest care, using all the skill I learned in the eight at Cambridge. The water was calm but I dared not go too fast, for the bow wave could easily wash into the boat. When we were a long way from the Danube I noticed Jo and Anna watching us from the deck. They were easy to recognise in their light costumes, and the woman in grey with them was presumably Watson's young lady, Anna's maid. After a few moments they disappeared. As silently as possible, we sculled up to the side of the Turbinia. The deck was only three or four feet above the water line, and it would be easy even for Holmes to get aboard. But for the moment we waited, hardly breathing as we listened for sounds from the yacht. A low cabin roof occupied the after deck, presumably covering the engine room and lighted by small windows. Forward of that was a small cockpit, tall enough for a man to stand in and completely enclosed. It would give entrance, I guessed, to the engine room. Beyond that structure was a very wide funnel, then, further forward, a small enclosed conning tower which Holmes said was the wheelhouse. On the bow deck another low roof lighted the saloon. A canvas splash guard screened some of the railings forward of the funnel. That would conceal us quite well. We closed with the yacht and Holmes pressed his ear to the steel hull, tilting our boat so that Bywell and I had to lean out on the other side while my brother shifted across with us. "Voices," Holmes whispered. "Language?" whispered Bywell, clinging on to the side of our boat. "German." Nothing more needed to be said. I led the way onto the deck, rolling under the wire rails while Bywell easily did the same. Watson climbed carefully aboard, but Holmes slipped and all but fell into the water, while the skiff shot sideways. Tubby, also boarding at that moment, scrambled frantically onto the deck while Holmes hung between the Turbinia and the side of our boat. The knees of his trousers dipped into the sea and his Panama fell in. Bywell and I held him under the arms and hoisted him up. There was a frightful moment before we made one final effort and got him aboard, but the boat and Holmes's hat floated away together. The five of us lay flat on the deck, near the wide funnel. "Rush and hold engine room, what?" came a mutter from my brother. I made no reply, for something cold and hard had inserted itself into my ear and a metallic click reverberated through my skull. From Tubby's sudden exclamation I knew that the same thing had happened to him. A huge hand seized my collar and, big and heavy though I am, I was hauled in one movement to my feet. An enormous, ugly, bearded face pressed itself into mine and the revolver was jabbed hard into my stomach. Beside me, three brutes out of the same stable were extending Holmes, Tubby, Watson and Bywell the same hospitality. Without a word being spoken, we were forcibly hurried below. No more than a few seconds had passed since we boarded the Turbinia. No-one on other vessels appeared to have seen the incident, all eyes being no doubt on the Royal Yacht. They pushed us into the cockpit near the stern, where we were flung down a few steps, our pistols being skilfully taken from us. The four giants tidily compressed us into the narrowest recess of the engine room. Three of them then left us as Fritz von Tarden, unsurprisingly, came nonchalantly down the steps. "I am afraid, Mr Holmes," said von Tarden, "that someone of your physique cannot board a small yacht without causing a considerable disturbance of the boat's equilibrium. When the Major accompanies you, one's reaction is to make an immediate investigation." He lit a cigarette in a silver and ebony holder. I was in front of Watson and behind Bywell and Tubby, who in turn were behind Holmes. Von Tarden jerked a thumb to the massive bearded bear who had picked me up so easily. The bear grunted and vanished amid a stink of sweat and spirits into the boiler room next door, where he began to shovel coal. His departure gave us a little more room. Von Tarden was armed with a sword stick. With him was a small man in overalls and with a pair of melancholy moustaches, who was adjusting a valve and who seemed to have some knowledge of engines, from the way he bobbed up and down to study dials. Von Tarden turned to him and issued some orders in German. "We're ready to set off," whispered Holmes. Von Tarden smiled lazily. "My dear Holmes, I had forgotten that you speak God's language. Yes, gentlemen, we are about to set off on a trip which you will remember for the rest of your lives. You need not fear. If you do nothing foolish your lives will be spared, but you will find yourselves somewhat incommoded for a day or two." As he spoke, the engineer said something to von Tarden, who nodded. Drawing a revolver, he put aside the sword stick and covered us with the pistol. "We have a little while yet to wait," said he. I was itching to get at him, but Holmes, at our head, was immovable. I knew he was no coward, but he had obviously decided on the better part of valour for the time being at least. While we waited I weighed our chances of retaking the boat. There were at least four enormous brutes aboard, besides von Tarden and the engineer. One of the brutes was shovelling coal. The rest must be in the saloon or on deck. The heat in the cramped engine room made the perspiration run down me in streams, and I could see that Bywell was in the same state, for, like me, he was breathing heavily. Tubby, of course, who loves heat, seemed unaffected, and behind me Watson was bearing up well. Being an old rugby player he would be useful in rough and tumble, but we had to wait for the moment. "Where is Mr Parsons?" asked Holmes. "He has come to no harm. He and his guests, Lord Lonsdale and Sir George Baden-Powell, are under guard, together with some of the crew, in the small saloon. Otherwise I can assure you, Holmes, that I would find better accommodation for you. However, once we reach our destination, you will all be transferred to another vessel and sent safely home." 10 "Von Tarden," said Holmes, "there will be the most fearful row at the highest level over this escapade of yours." "War," added Tubby. "Give up now, Fritz, old man." Von Tarden smiled again. "I can give you my word, Major, and you too, Holmes, that I am acting on my own initiative today. My associates are not German, although they speak the language. They are a motley crew of anarchists and the like, mostly Russians. This gentleman, my engineer, is a Servian from Bosnia-Herzegovina, who wishes to strike a blow against the imperialists. He would, I grant you, have a greater effect were he to strike against the Austrian Empire, but I suppose he is following some logic of his own." "You mean," asked Tubby, "Berlin knows nothin' of this?" "Not a thing. I imagine I shall indeed be embroiled in a fearful row when I get the Turbinia to her destination, but I have tried for the past two years to get our bone-headed bureaucrats to take notice of the work of Mr Parsons, for whom I have the greatest admiration. You see, Major, if Great Britain starts to build turbine-driven capital ships, the imbalance of naval power between your country and mine will become intolerable. I'm sure Holmes will agree." Holmes said nothing, and for a while von Tarden smoked quietly, all the time keeping his eyes on us and his revolver covering us. With the hiss of steam and the steady sound of coal being shovelled in the boiler room, it was difficult to hear much from outside. Also, the heat affected me so that I became slightly drowsy. "What happened to Parsons's crew?" asked Holmes. "Some are in the saloon, as I said. The rest were duped ashore." After that nothing more was said, and there was a kind of stalemate in the overcrowded engine room, with only the Servian moving around as he looked at the dials and fiddled with valves. At length he nipped out onto the deck. I heard him above us, there was the slithering rumble of a rope sliding over the deck, and he hurried back, having apparently cast us off. He considered some dials, turned some valves, rang the engine room telegraph loudly, and the little ship quivered, nothing more, but we all shifted our balance slightly as we got under way.