| Back to Mycroft Holmes Title Page |

THE DIFFERENCE ENGINE Mycroft is also available at sambonnamy.110mb.com

August 1896 |

|

| In which the ingenious Major Winstanley gets his fingers burned by a calculating Colonel and a calculating machine. | © paperless writers 2000 - 2004 |

|

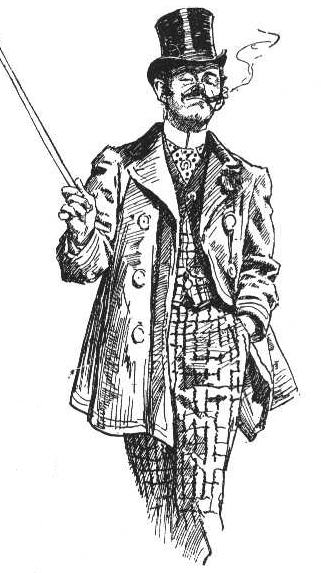

THE DIFFERENCE ENGINE August 10th - 17th 1896 Footnotes in red are clickable "Good heavens!" exclaimed Stephen as we began to cross the Park. "Has London gone mad?" "What do you mean, dear?" Stephen pointed his cane at the hordes of young men - office clerks as well as loungers - who were strolling with their jackets over their arms. "I know it's a hot summer, but surely men can keep the proprieties?" he grumbled. "What next? Bathing costumes?" "Don't be so stuffy!" I laughed, and clasped his arm tighter. A gruff salute came from General Stracey pedalling by on his bicycle painted in the red and blue of the Guards. Stephen acknowledged, and I was gratified to see that the General also smiled at me. Not everyone was cutting us. "Look," I went on, "there's Lord Royston not wearing his jacket! Take your own off. I dare you." He demurred, but not without a tender smile, and, as we strolled across the crowded Park, I could gave him a loving appraisal. From the crown of his light summer hat to his lavender spats and gleaming shoes he was every inch a gentleman, and a remarkably handsome one at that. And he was all mine - albeit illicitly! Certainly, the summer of 1896 was a noteworthy one. I was getting over the final breach with Mycroft, and both Stephen and I could see the humorous side of our entanglement. Joanna and I had talked over Mycroft's behaviour, concluding that his weakness had got the better of him. He and I rather warily became friends again, and were able to treat our breach in a somewhat detached way, probably because we both lived bohemian lives. However, I was now less inclined for adventure, and I determined that the recent brush with Sir Ettrick Ralph's syndicate would be my last escapade. I had found the love of my life, and that he loved me I had unshakeable proof. When we began to live together, Stephen offered his resignation to the Prime Minister. Lord Salisbury was shocked and disappointed, but he accepted the resignation. It was I who berated Stephen for throwing up his career for my sake. Yet I felt deeply moved. Mycroft would not even live outside the Diogenes Club for me. Society had responded to our illicit liaison pretty much as we expected. Of those who knew about us, some cut us, others were wary, and a few accepted what we had done. Those who accepted us, I noted, were those who knew Emmeline. Many people, however, knew nothing of our liaison, and some of Stephen's acquaintances assumed that I was his wife. Now that he was at leisure, Stephen left for Northumberland on the tenth of August ready for the start of the grouse shooting season on the twelfth. Marie and I settled into a tranquil routine in the flat off St James's Square. I feared that the stolid Northumbrian country folk would be scandalised by my presence at Bywell, no matter what excuse was made for it. Next morning a letter came. "My dearest darling," it read, "I had been at Bywell no more than an hour when I found the Prime Minister himself waiting on me. He had travelled north ahead of me on business in Newcastle, and called to offer me a post that I feel I can hardly turn down, despite my beliefs that I am not fit for public office. "I made it clear to him that I had made my choice between public office and my own dearest Anna, and that I have no intention of giving you up. He then said that he did not mind that we remained together, as long as it does not become public, but that the needs of the country were more important than my own personal inclinations. (What would Gladstone have said, I wonder?) "When I asked Lord Salisbury what he meant by the needs of the country, he explained that Major Winstanley has been put in charge of a scheme to build a new calculating machine for the Government, and His Lordship wants me to be Junior Minister in charge of the scheme. "I gather that the plans for this machine date back some fifty years, and that it simply could not be built in the Forties, although the inventor, one Charles Babbage, was meticulous in drawing up the plans. "That is all I know at present, my darling. Because the Premier is so insistent, I shall abandon my shooting and return to you by the earliest train. I'll be hard on the heels of this letter, and cannot wait until once again I have you in my arms. "One confession I have to make. The P.M. is very keen for Holmes to be brought into the scheme. I had not the nerve to tell him that I have no communication with Mycroft Holmes, because I was conscious of the scandal it might bring to Emmeline. For those scruples and that lack of courage, I fear that I have put both of us into a difficult position." The position could have been difficult, for, since Mycroft's feigned demise at Grange-over-Sands, Stephen had met him only under extreme necessity, and could not contemplate working with him for long. Yet the Prime Minister's offer would encourage Stephen to return to public life. I decided to attempt smoothing the troubled waters by speaking to Mycroft. Marie sent a street boy for a cab, but returned with a worried look on her face. "Mam'selle, there is a man standing outside. I do not like the look of him." A peep through the lace curtains disclosed a tall, spare, elderly man standing across the road and wearing a light summer overcoat in defiance of the heat. "I imagine he's waiting for someone, Marie, or a cab." "Except that he was there an hour ago, mam'selle, and I have seen him let at least two cabs go by. I think he is watching this flat." It was no-one I knew. He had a military air about him, and I had not lived with Mycroft Holmes for over seven years without learning something of observation, so I duly noted the salient points about him: his height - about six feet - his lean figure, his age - about fifty-five - his well-groomed appearance, and his tanned cadaverous face with its high forehead. I also noted his habit of swaying his head slightly, as though short-sighted. "Keep an eye on him, Marie, and if he should call, do not answer the door," I instructed her as the cab drew up. The cab, a four-wheeled growler, screened me from the stranger, but I noticed him look after me as I drove away. When I reached the Diogenes I waited for a few minutes just inside the doorway, but saw no-one obviously following me. The memory of being abducted from the Mall flashed through my mind as I waited, and with a shudder I passed into the club entrance. Old Dinwoodie took my card for Mycroft, and I had to marvel at how the old man persisted in working at an age when most people are dead. Through the glass doors I observed the members assiduously ignoring one another in the common room. "Will there ever be any chance of ladies penetrating the secrets of this club, Dinwoodie?" I asked as he fumbled with my card and his salver. "Not while I'm alive, Miss Bainbridge," he quavered. "This lobby's the furthest that members of the sex can go, unless it's to the Strangers' Room. That's why that brass strip's been let into the floor." "What does it mean?" I asked. In my day there had been no such thing. "Well, miss, a couple of years back there was this Colonel Moran what wrote to the papers accusing members of keeping their mistresses here in secret. Caused a right old to-do, that did. The Secretary wrote back and gave him a roasting, but mud sticks, as they say. So the Committee decided to put this brass strip in the floor to make it clear that was as far as the sex could go. See, it allows you into the Strangers' Room but not into the main hallway, and if you look, there's a motto in Latin engraved there in the brass." "O feminae, ne plus ultra," I read, and recalled how Mr Dalziel encountered the formidable Martine in the Strangers' Room, one of the few women who ever got into the Diogenes. "'No further for ladies' is what it means, so I'm told, miss, and there's the barrel of Diogenes etched in at either end. First meeting the Committee had had for - oh, about ten years, I think. Mr Holmes moved the motion." "What did he say about the Colonel's accusations?" I knew, but I wished to hear Dinwoodie's view. "He just about exploded, miss, as we all did. Mistresses indeed! None of that sort of thing goes on here, not even with these New Women. Mind you, there's that young Lady Bywell, and what a carry-on she's caused. It was different in my young days under old King Billy. I worked in a club where the gentlemen had their mistresses everywhere. You didn't dare go into the Turkish bath for fear of finding one or two young ladies cavorting about in the bare buff, and as for the goings on atop of the billiard tables - " "I don't think you should tell me that," I said, although secretly I should have loved to hear some of the old man's tales of life before Queen Victoria. The goings on atop of the billiard tables, however, touched a nerve that was still tender. "No, Miss Fairbridge, for it's made you blush. But women, well, nowadays we do let them into the Strangers' Room on occasion, as long as the door stays ajar so as Harris can look in. Here, you're a relation of Mr Dalziel, ain't you? How is he these days, miss? Still keeping well? He was a right card, was Mr Dalziel. Many's the laugh Harris and me have over what he used to do." He tottered away, unsteady as ever, and I wondered what he would say if I told him the truth about W. H. Dalziel. I had blushed, not at the revelations from Dinwoodie's younger days, but because Colonel Moran had been right, and I had been the mistress in question. At length Mycroft appeared and we went into the Strangers' Room. We exchanged a handshake and fell into small talk. "So," I said, "it was you who moved that ladies be allowed no further than the lobby?" "Well, Emmeline wanted to get in once. We have to take a firm line with you New Women, you know. But surely, Anna, you did not come here to discuss the admittance of ladies to the Diogenes?" I told him of the letter and he nodded sagely. "Good! I'm glad they've given Bywell the post. The machine itself? Well, I know little more than you do. The inventor, one Babbage, died about twenty-five years ago. The machine, complicated though it is, can be built and could have been even back in the thirties. The problem was that Babbage had no proper organisation and rowed with his engineer. Major Winstanley will surely face no such obstacles. Nothing will stand in his way." 1 "But what will they do with it?" "Use it for the Treasury, I should think. I'll find out, of course. Now, who is that man across the street who is obviously watching the entrance of the Club?" "Light summer overcoat? Tall, spare, military-looking, elderly?" My voice betrayed the chill I felt. "You know him?" "No. Do you?" "Apart from the fact that he is a former Army officer - probably India - is a member of the London Library in St James's Square, and has undergone financial losses on the Stock Exchange, I know nothing about him. As for his being elderly, I would put him at no more than five years older than I am." "I know your methods, but I can't see him as you do. How can you deduce so much about him?" "You noticed his military bearing, Anna. The light overcoat worn even in this summer weather shows that he became used to intense heat, which suggests tropical service, Indian Army rather than West Indies, I fancy." "Why India?" "He does not look robust enough to have survived the many diseases endemic in the West Indian service. He wears his coat loosely over his shoulders, however, showing that he has become partly used to the British climate again and has therefore been home for some years. His face is not that deeply bronzed, which also indicates a return some years ago. The London Library ticket is protruding from his waistcoat pocket, the library itself being at no great distance from here." "Financial losses?" "He is a neat man, fashionably dressed." "I thought him very smart, too." "No, Anna, there is a wide difference between the neat man and the smart man, as the hunting writer Surtees points out. The smart man is but the creature flourishing for the moment, while the neat man is always neat whatever he has on, like our friend there. Note that he wears his overcoat with some panache, but it is not new - the cuffs are slightly frayed. The nap of the light grey hat is worn in two places. Therefore, although he likes to dress well, and is something of a dandy - note the good quality of his cane - he cannot at present afford to dress as he would wish, which suggests some financial loss. The most likely places for a man of his standing to lose financially are the race track and the stock market. He has not the horsy look about him, which leaves the stock market." "Or the card tables?" "Possibly, but he has not the flash look of the habitual gamester. He looks extremely respectable: shabby gentility surrounds him like an aura. He is obviously used to moving in polite society." "He's followed me here." Mycroft blew heavily through pursed lips. "This sounds serious. How do you know he's followed you?" I explained how I had seen him from the flat. "I looked for him after I arrived here, but saw no-one. But there's no doubt that he has followed me." "We shall have a cab and get you back home safely. Do you still keep your revolver? Still in practice? Good." "What's good about it?" I asked sharply. "I'm being followed by a strange man and you're hinting that I may have to defend myself at pistol-point. Do you think it has anything to do with this Government business that Stephen's taken on?" Mycroft puckered his brow. "Hardly, unless he is a secret agent. But surely he would not yet know of Lord Bywell's involvement in the scheme. And even then, your flat is not Bywell's official address. No, the gentleman is obviously interested in you. Could it be something to do with our little Continental contretemps of last year?" "Oh God! What if he's from Grüner! Mycroft, I'm frightened. Will you come back to my flat with me? I'll feel safe once Stephen's home." Mycroft took one last look from the window before leaving the room. "Ah ha! Could it be, I wonder? ... Harris, go out by the back door and get us a cab. Do not let the man across the street see you." Despite my urgings, he said nothing more. We took the cab together. The stranger did not seem to follow us, but once I was home, I said I should not feel safe until Stephen returned about tea-time. Mycroft saw me into the flat, carefully scanning the street, and advised me to lock the doors. When he had gone, Marie told me that the stranger had hailed a cab as soon as I had driven away. "I was worried, mam'selle. I knew he was following you. I have loaded your revolver and put it in the drawer of your writing desk. I have also loaded this." She produced from her apron pocket her wicked little .41 calibre double-barrelled derringer, which had been the finish of Karl-Gustav Grüner. "I shall keep this with me at all times." She glanced out of the window and turned pale. "Mam'selle, there he is again! Oh, but thank heaven! Here is his lordship at last with Mr Roberts." I told Stephen of our fears as soon as he came in. His first move was to go outside, accompanied by Roberts, to confront the stranger, who was still there. From the window, Marie and I watched as the stranger, seeing Stephen emerge, hurried away, hailing a passing cab, and driving off at a furious rate. Stephen returned, looking angry. "I don't know who he was, but he realised that I meant to have a word with him. One of Grüner's agents, you think? I'll call on Straightfellow and see if he can put a man onto him. Don't worry, there's nothing to be afraid of. Now, Marie, I'll have a bite to eat and, Roberts, if you'll go and run my bath - " As soon as we were alone we were in each other's arms and, had Marie and Roberts not been about, I verily believe we would have been in bed within minutes. My ardour for Stephen, I realised, surpassed anything I had felt for Mycroft. I could hardly contain myself until bedtime. That night we made love as if for the first time. We had not been parted since we began our liaison, and we were hungry for each other. Next morning Mycroft called after breakfast. Stephen discreetly withdrew, but Marie stayed as chaperone. "I've discovered the identity of your mysterious follower, Anna," Mycroft said gravely. "It's as I suspected. Did you know that Professor Moriarty had two brothers? The younger was a station-master in the West Country until the death of the Professor endowed him with a goodly share of his brother's ill-gotten wealth. He - the younger brother - went into retirement. The second one was in the Army. The man who is taking such an interest in you is that brother, Colonel James Moriarty." I sat down and stared at him. "It must be unique for living brothers to share the same Christian name," he went on, "but it is a fact that both the Professor and the Colonel were christened James. How their parents got away with it I shall never know." 2

"Let the Archbishop of Canterbury worry over that, Mycroft. I didn't know Professor Moriarty even had a brother." "Oh, yes. After Sherlock rid the world of the Professor, the Colonel was vehement in his brother's defence. He wrote several letters to The Times, I remember, which quite annoyed Watson during the period when he thought Sherlock to be dead. I never saw the Colonel before yesterday, but his habit of swaying his head reminded me of his late brother, and it was with that suspicion in mind that I pursued my enquiries." "Whom did you ask?" "Watson. I observed, you remember, that the Colonel had a London Library ticket in his waistcoat pocket. Watson is a member of the library and a friend of Lomax, the sub-librarian. He gave the description to Lomax, and got the name right away. He also came back with a little bonus - the list of books the Colonel has borrowed or consulted over the few weeks that he has been a member." "What will that tell us?" "Firstly, for a member of only a few weeks' standing, Colonel Moriarty has been an assiduous borrower. Secondly, he has an intense interest in mathematics, since his borrowings and consultations have all been in that discipline." "Wasn't the Professor a mathematician?" "A brilliant one." "Well, can't you see a connection, Mycroft?" "Between the Colonel and the calculating machine, you mean? Yes, Anna, I can, but I don't see Moriarty's purpose." He rose. "The Colonel is almost as dangerous as the late Professor - " "My God!" " - and there can be little doubt that something is afoot. Sherlock is the man to tell us what. This little problem of the Colonel and the calculating machine is just the sort of thing he will love." "I don't think there is a problem, Mycroft. I think Colonel Moriarty plans to discover as much as he can of the calculating machine for his own ends. If he's as dangerous as you say, I shall be extremely worried about Stephen." I took my pistol from its drawer, checked that it was fully loaded, and put it in my pocket. Mycroft sat down again and slowly took out his pipe. "Do you mind?" he asked, as he filled and lit it. "I remember how much distress Hearst and I caused you once with our smoking. But, yes, Lord Bywell could be in danger. Yet I find it difficult to reconcile Colonel Moriarty with the world of secret agents and foreign powers, if that is indeed the world he moves in. I should have thought the underworld would be more his metier. Yet he does not look like a criminal. But then, neither did the Professor." "If he's Moriarty's brother he must be up to no good." "He certainly took the side of the Professor and refused to admit that he had been in any way in the wrong, despite all the evidence that Sherlock had collected. Sherlock also compiled a quite interesting index entry on the Colonel. I once glanced through it, but it will repay closer study. In fact, I can go to Baker Street and read it now." He rose and picked up his hat. "We must watch the Colonel. By the way, keeping that revolver in your pocket ruins the line of your dress." After Mycroft had left, I told Stephen about my fears. He listened carefully. "I shall certainly take Sherlock Holmes's advice, should he have any to give. In the meantime, I have to go to Whitehall to meet Major Winstanley. Don't worry, my love." With that, he kissed me and left, while I scrutinised the street for Colonel Moriarty. Seeing no sign of him, I rang for Marie and entered upon an urgent consultation with her. "Yes, mam'selle, Mr 'Olmes he is quite right about your pistol ruining the line of your dress. I can run up a strong belt and holster of webbing, to be worn discreetly under the arm and beneath your jacket, or I could make a belt for you to wear beneath your blouse, just above the waist. In fact, I will make both, one for the heat of summer to wear with a summer blouse, and the other for later in the year when you wear a jacket." All morning Marie's sewing machine busily whirred in her room while I kept watch at my window. The Colonel did not appear, but when Stephen returned late in the afternoon he brought Tubby Winstanley with him. "Bywell tells me Moriarty brother watchin' yer, Anna," rapped the Major as soon as he entered the room. "Don't like sound of it. Shall put someone onto him. Meanwhile, came over to suggest you and Bywell move quarters pro tem. Fitz-Forsythe to arrange, what?" "Sir Hugo Fitz-Forsythe," explained Stephen, "is the Treasury official who's dealing with all financial aspects of the Babbage Scheme, as it's now known. He will arrange temporary accommodation for us." "And don't worry re domestic irregularities," added Tubby blandly. "Fitz-F knows nothin' of livin' arrangements you two. And now, Anna," he continued, "tell yer somethin' re Difference Engine, what?" "The difference engine? What is that?" "The Difference Engines were the early calculating machines devised by Babbage," explained Stephen. "We have the plans for what we're referring to as DE1 and DE2. What the Major wants is to build DE2, the more advanced model, then, assuming that it is a success, we'll go on to build the Analytical Engine, which is much more advanced." "And what will these engines do?" Here Tubby broke in, spluttering in his excitement. "Difference Engine. Best way celebrate Queen's Jubilee, show world we still mean business." "So you're doing this for next year's Jubilee?" Huddled in a chair in the sunlight by the window, Tubby winked, the perspiration beading on his brow. "Diamond Jubilee best excuse I could think of, old girl. Must get money from graspin' Treasury officials somehow. Been wantin' build Difference Engine ever since Winchester. Maths beak had copies of plans, knew Babbage personally. I made copies, nurtured dream ever since, what? Ah, coffee." Marie brought in a tray with cups and a steaming pot. Tubby gratefully accepted his cup and drank noisily. "But what will the Difference Engine do?" I said after Marie had left. He began to rattle away furiously, his tongue scarcely keeping pace with his ideas. "Make all calculations easier. Improved gunnery - better ships - hasten arrival of submarine - speed wireless telegraphy experiments Signor Marconi - lease out to capitalists - build faster locomotives - improve internal combustion engines - make motor cars available middle classes - electricity for all homes." As he ran out of breath Stephen stepped in. "Motor cars for all, Major? But they aren't allowed to go faster than walking pace." Tubby tapped the side of his nose. "Legislation on way, old chap. Man with red flag doomed. Where was I? Ah yes - motor cars - electricity - develop kinematograph as means of informin' masses - perhaps with voices, what? - devise improved water supplies - drainage - improved surgical instruments - improved telephones - better gramophone recordin's - improved postal service - major improvements all types industry - perhaps even get flyin' machines, what?" 3

Red-faced, he paused to breathe. "Flying machines!" I exclaimed. "Why not, Anna? Just imagine, able fly here to Scotland, what? Faster than train. Leave more time for shootin'." "This calculating device will perform all these miracles?" "'Course! All these miracles, as yer call them, depend on doin' the maths. F'r instance, development of submarine hampered unless we can solve difficult problems on water pressure. This machine will clear that hurdle for us and - good God! Is that the time? Must dash Cricklewood. New parts due. See m'self out. Lovely coffee." With that, he positively bounced out of the room while Stephen shook his head. "He's like a boy with a new toy," he chuckled. Later that morning a couple of quiet men called and told us not to worry if they were lounging in the street for the rest of the day. We understood that they were from Tubby's department, and although the Colonel appeared and began to loiter in his usual spot, the two men approached, said something to him, and watched him out of sight. Marie brought the webbing belts and holsters she had made. A skilled needlewoman, she already had my measurements and I was not surprised that they fitted perfectly. Marie, of course, was not satisfied until she had fussed and made adjustments to the last fraction of an inch. I could now wear my pistol without its being obvious, although it would take some time for me to become used to the rather elaborate harness that Marie had made. "You must make the same for yourself," I told her. "Thank you, mam'selle. I have already taken the liberty of doing so. I am wearing it now." From beneath her blouse she produced her derringer. "It is kept at the waist, mam'selle, where I can reach it easily. A little immodest when I take it out or put it away, but I do not think it is noticeable when I am wearing it and it preserves the line of the dress." Later a cab called and took us to the Advocate-General's Office, where Tubby gave us the keys and address of an apartment on the other side of Kensington Gardens. We spent the next two days making ourselves comfortable there, so it was not until the third day that I was able to persuade Stephen to take me to see the mysterious Difference Engine. We went by rail to Cricklewood, from where a cab conveyed us to a huge rambling villa, "The Pines", built about thirty years earlier. Tubby met us, and conducted us into a ground floor room which had been made into a small office. "Delighted see yer, old girl! Beefy presently in workshop supervisin' fittin' of parts. Look round? Don't see why not. This way." He took us through the house to the back premises, where the stables had been fitted out as a workshop. There he handed us over to Beefy, who was supervising a small team of men busy at work benches. "These men are watchmakers grinding down the more delicate small parts," Beefy explained. "I suppose Tubby has told you how long he's wanted to build this machine. He's assembled a number of skilled toolmakers, watchmakers and surgical instrument makers, to attend to the precision cutting of the smaller parts. The bigger parts are fine-machined and polished in what was the coach house. Come along back to the house, and I'll show you what we've got at present." We returned to the house, and Beefy took us into what must originally have been the dining room. The folding doors into the next room had been removed, and there at one end of the huge empty space stood a solid iron framework. A squat metal contraption stood beside it. "The framework is for the Difference Engine itself," explained Beefy. "The machine beside it is an electric motor, powered by the steam generator downstairs." Taking us downstairs, he threw open a door and showed us a small steam engine in what looked like a former outhouse. Stephen's eyes lit up. "That's surely the generator from Armstrong Whitworth?" "Correct," said Beefy. "That's what you got us, my lord. It's not being fired up at present, for the Difference Engine is by no means ready, but we've decided to drive it by electrical power from this generator." Stephen and I returned that afternoon to our temporary accommodation near Kensington Gardens. A small commotion was occurring in the street as we alighted from our cab. The two quiet men who had seen off Colonel Moriarty were being hustled into a police van, and no sooner had they been driven off than Superintendent Straightfellow himself called. "Afternoon, my lord. Afternoon, Miss Weybridge. I've just called in passing to say that you'll have no further trouble from those two." "But, Superintendent," exclaimed Stephen, "they were Government agents protecting us on the orders of Major Winstanley!" Straightfellow's mouth fell open. "But we had a complaint that they were harassing visitors to your flat by begging. By damn!" With that he dashed downstairs and hurried off after the police van. Stephen looked grave. "A complaint from Colonel Moriarty, I'll wager. Has he tracked us down already?" He looked out of the window, peering through the net curtains. "Good Lord! No, don't come to the window. He's just driving past in a cab. He glanced up at me. He must have followed those two Government men. The Major should have put two new men here before we moved. I'm surprised he overlooked a detail like that." "I wonder whether all's well between him and Lucy Alnford-Ross," I mused. "It was bad enough when Mycroft was completely spoony over - over you-know-who, although he seems to have recovered. But if the Major goes the same way, there could be disaster ahead of us." "It may adversely affect his judgement, you mean?" asked Stephen. "We can certainly do without that." We were silent for quite a while. Whatever Moriarty was after, he was determined not to be thrown off our track. His tenacity was amazing, and I decided to speak somehow to Mycroft, if I could get away without the Colonel's seeing me. The problem of Tubby's unusual absent-mindedness also worried me. We could not afford slackness of thinking on his part. It was clear that we needed the energy of Mycroft's mind behind us, for his affaire with Emmeline seemed no longer to be affecting his thinking. Unfortunately, his superior had now succumbed to what the romantic novelists call the wiles of Cupid, and perhaps those wiles would endanger us even in our retreat. A little later another caller was shown into our drawing room. A tall, saturnine man of middle age, with lank dark hair and a nervous manner, took the seat that Stephen offered him. He huddled on the edge of the chair and seemed very much ill at ease. "Anna," said Stephen, "this is Sir Hugo Fitz-Forsythe. Sir Hugo, my - er - Anna." "Delighted to meet you, Lady Bywell." Sir Hugo bobbed up, offering a limp hand and an uncertain smile, but I was taken aback by Stephen's blundered introduction. Blushing to my roots, I took our visitor's hand and sat down. For the first time I was uneasy about the ring that Stephen had given me, a simple gold band which I wore, to please him, on my wedding ring finger. Until then I had satisfied my conscience that it was merely a signet, but now I sat twisting and playing with it as a conversation got under way. It was almost entirely about the Difference Engine, and although Stephen seemed to understand it all, I was quickly lost and began to observe our visitor. One thing I noticed was that Sir Hugo's eyes looked everywhere but into Stephen's or mine. His voice, too, was odd, for someone in a position of influence and power. His intonation suggested uncertainty, and he frequently gave a little gasping laugh which I quickly found irritating. Once or twice he glanced at me, smiling uncertainly, and glancing quickly away as I returned his smile out of mere politeness. At length we had tea and the business dropped away into small talk. Here I was able to contribute, but I noticed that Sir Hugo said little or nothing, merely smiling and gasping at each of us in turn. "What a strange man!" It was Stephen who voiced that remark as Sir Hugo's footsteps faded down the stairs. "Anna, didn't you find his manner odd?" "He has no small talk." "I noticed that. Do you think he realised we're not married? Do you think that disconcerted him?" I pondered. Perhaps he had realised that we were living in sin. "Did his talk about the Difference Engine make sense?" I asked. "Yes, he knew it all right, but he seemed to be so ill at ease even then." "I shouldn't worry about it, darling," I said. "He's under you, isn't he?" "Yes. I hope I find it easy to work with him." Stephen worked on papers until fairly late, then came to bed and found me ready for him and impatient. We worked so hard for an hour that we slept like the dead, which is why we noticed nothing amiss until late the following morning. We woke suddenly, for the sun was pouring into the room and the morning was obviously far advanced. "Good God! It's half past nine. Where's Roberts? Where's Marie?" said Stephen irritably as he climbed out of bed. "They should have knocked long ago." Putting on a dressing gown, he left the room in search of our erring domestic staff while I went to the bathroom. Suddenly he burst in, white-faced. "Anna, get dressed quickly. We've had a burglary. Poor Roberts is unconscious and Marie's been tied up and gagged." In my bathrobe I flew to Marie's room. The poor girl was sitting on her bed in tears, rubbing her wrists where they had been tied by cords which Stephen had cut. She pulled herself together and rapidly told me what had happened. "It must have been after midnight, mam'selle. I was wakened by someone holding his hand over my mouth while another tied me up. Then they gagged me and left. They said nothing all the while, and I never saw them again. Oh, mam'selle! I am so sorry. I was helpless." She flung herself onto me while I comforted her. "There was nothing you could do, Marie. Don't blame yourself." "But what have they taken?" "I don't know yet. Lord Bywell is investigating. Poor Roberts is senseless, apparently." "Mon Dieu!" She scrambled to her feet. "We must send for a doctor. I shall go, mam'selle." "You'll do nothing of the sort. As long as you're uninjured, I can leave you and go myself." I was forestalled by Stephen, who came in wearing clothes which he had obviously pulled on hurriedly. He ignored Marie's shriek of embarrassment as she snatched up her dressing gown and pulled it on over her night-dress. "I've sent a boy to the surgery and am now going to find a policeman." "How is Roberts?" "He's coming to. They gave him a real beating, whoever they were. Anna, you'd better get dressed and look to Marie." "I am not hurt, my lord," said my maid. "I am enraged. If only I had got hold of my little derringer!" There had been two of them, both masked and wearing black clothing. After binding and gagging Marie they had obviously found Roberts in his room. He had tried to tackle them, being savagely beaten for his pains. We dispatched him to hospital while Stephen and the inspector who called searched the flat to see what had been taken. Only the plans for the Difference Engine were missing. "They're not a great loss," said Stephen. "There are copies. But it lifts this burglary out of the domestic plane into the political, or even the diplomatic." "I can't understand how you heard nothing, ma'am," said the inspector. "Your maid says she struggled and made quite a bit of noise. There must have been noise coming from the valet's room, too." I could not reply, merely flushing with embarrassment while Stephen caught my eye and smiled briefly, despite the seriousness of the whole business. "We were sleeping soundly," he replied. "Besides, the servants' rooms are on a different floor. They'd be professionals, I take it." "Without a doubt, my lord. They knew what they were looking for, and took nothing else. Where were the papers?" "Lying on my desk." "How many people would know that? Your servants? Her ladyship here." I had to turn away, for I must have been crimson. "No-one else," said Stephen. "Well, my lord, the superintendent will probably speak to you because of the nature of the theft. But we've no clues to follow." "That," said Mycroft later, "is precisely why Straightfellow came to me." Stephen and I were in our own sitting room with Mycroft, Straightfellow and Tubby Winstanley. Tubby, as usual, was crouched over the fire, which we had lit for him, while the rest of us were clustered near the open window on that warm summer's afternoon. With us was the inspector, who had returned with Straightfellow to point out various things to him, how the raiders had entered, where the assault on Roberts had taken place, and so on. Marie and I had visited the hospital to see Roberts, who was still groggy with a bandaged head, but was otherwise his old self. The inspector took his leave, addressing me as "Miss Weybridge" and giving me an old-fashioned look. I realised that Straightfellow had had a word with him. My reputation will be in ruins, I thought. The suspect was obvious. "You can bet your best boots, Mr 'Olmes," affirmed Straightfellow, "that he's hired two of his late brother's ruffians to do this job." "Point is," said Tubby, "who's interested in plans? Only a government has money enough to build this machine. Old friend von Tarden springs to mind, naturally, but any foreign power could be culprit." Not even Mycroft had a ready answer, so the best that Straightfellow could do was track down Colonel Moriarty, which was surprisingly easy. A couple of hours later our plain clothes inspector called with a copy of The Times. Avoiding my eye, he spoke to Stephen. "There you are, my lord," he said, pointing to a paragraph. "The gentleman's announced he's off to shoot in Northumberland. Could be a false trail, of course, but Mr Holmes and the super think it's genuine. Establishing an appearance of innocence, Mr Holmes says." After he left, Stephen sent some wires and later he and I found ourselves at odds. "No, my darling, you cannot come. Richard Winstanley and I are going north for the shooting, supposedly. But you will not make up the party. I forbid it. Father would have a fit if he found out about us, even though he does like you." "Why should he find out?" "He will be joining us for the sake of appearance. Dear old soul, he will know nothing of my real purpose in going north. We'll get him out of the way if anything serious occurs with Moriarty." "But you need someone who knows how to handle a revolver, Stephen. You can't use one properly, you know that. Beefy's not a bad shot, but he's not as good as I am. Now I've done this sort of thing before. I've helped chase spies and - and even supposed vampires. I shot von Frimmersdorf." "And what happened to you last year in Switzerland and Bethnal Green? Particularly Bethnal Green, when you let Holmes goad you into taking up that foolhardy case. You still have bad dreams about it all. No, Anna, you can't come with us. I'll have all the help I need from Winstanley." "But what if I'm still in danger?" I asked, cunningly. "I need to be with you for safety, don't I?" Stephen smiled. "You know perfectly well that Holmes now believes that you were never in danger after all. Moriarty merely followed you because he almost certainly thought that you were acting as a messenger over the plans for the DE2. His suspicions probably began when you visited Holmes at the Diogenes." "It will be dull without you - " "Then call on your friends. Now, I need Marie to pack for me, since the hospital won't allow poor Roberts home for a few more days." After she had done Stephen's packing, Marie and I had a little conference, the upshot of which was that early next morning, after Stephen had left, my maid and I did some packing of our own.

Tuesday August 18th "Worse than Baron Grüner, mam'selle?" Marie, laying out my evening wear on the bed, paused with wide-open eyes. I had just come out of the bath, relaxed and ready for the entertainment that we had planned for the evening. "Yes, if what Mr Holmes says is true, Marie. And I have no reason to doubt it. Worse than Haynes, even." Marie gasped and shuddered. "Do not mention the man Haynes, mam'selle. I still have dreams." I turned to the window and looked out over the Northumbrian countryside, lit up by the evening sun. We had followed Stephen to Newcastle by a later express, and, after much consultation of an Ordnance Survey map, had taken a local train to a small inn at Riding Mill, a village on the banks of the Tyne a scant couple of miles from Stephen's estate on the north side of the river. We made good time on the express, reaching the Duke of Wellington Inn tired and pleased to find rooms available. A good night's sleep gave us the energy to explore the district the next day. We had quickly learned the whereabouts of Bywell Manor, across the river from the next station, so we ventured by train to spy out the land. It was sobering to remember that Colonel James Moriarty was also in the vicinity. The Colonel, we knew from The Times, was staying at Broomley, a mile or two away from us. "What I do not understand, mam'selle, is why Colonel Moriarty put that announcement in The Times that he was coming north for the shooting. After the burglary, I would have thought he would lie down and keep his head low, as they say." "As Mr Holmes said, Marie, a man who makes his movements so plain is likely to remain free of suspicion. There is apparently nothing to link the Colonel with the burglary and the assault on you and poor Roberts." Guns slapped their dull distant echo across the fields. "That may be his lordship shooting, mam'selle. What will he say when he finds out we are here?" "He need not know, Marie. You arranged for someone to come into the flat and redirect any letters?" "Yes, mam'selle. John - Dr Watson - he will do that. Mr Roberts he will be indisposed for a few more days." "Very well. We shall return before Roberts comes out of hospital. Are you sure you understand what we are to do here?" "We are to watch the Colonel in case he goes near Bywell Manor. But how are we to get to the place - what is it called? - Brump - Broomley? By walking?" "I've hired a trap and we shall drive ourselves." "Can you drive, mam'selle?" "Good heavens, yes. When I went out West I drove from the age of twelve. Besides, if Mycroft can do it, anyone can. And it isn't far." "And we shall wear these clothes such as you and Mrs Winstanley wore in Ireland, mam'selle?" She held up my evening outfit - a green jersey and twill breeches. "What will the people say? Think of the trouble you had in Ireland when you dressed so." "We shall be very discreet, Marie. These clothes will enable us to remain unobserved in the countryside." "Unobserved? Mam'selle, we shall stick out like the proverbial sore tongue! Everyone will comment on us." "Not if we are discreet. I intend us to be almost invisible against the trees and hedgerows. But we shall set off quietly and return quietly." "And if the Colonel strays near the Manor?" "Well, we can warn Mr Winstanley and Lord Bywell." "And then, as they say, there will be fireworks." Another fusillade rattled across the distant fields, and Marie followed my gaze out of the window. "We are up against a dangerous man, you think, mam'selle?" Dangerous indeed. Mycroft, as he had promised, had consulted his brother about the Colonel's record. I had not yet told Marie, and her dark eyes once more opened wide as I described what Mycroft had found. "Four murders!" "At least, Marie." Marie blew out her cheeks and felt at her waist. I, too, was reassured by my little .32 Webley lying in its holster and belt on the bed. "Is he a good shot, mam'selle?" "He's here for the shooting, so I suppose he must be." "As good as you?" "I hope we never have to find out." "I am grateful to you for teaching me something of shooting with the pistol, mam'selle. But why is Colonel Moriarty not awaiting the gallows?" "Nothing can be proved, Marie. The Colonel is as clever as his late brother in covering his traces. Mycroft says that the earliest case seems to have occurred in 1889, on the Colonel's return from India, and concerns the mysterious death of Lord Berthill. He breathed his last in the grounds of his own estate in Surrey, impaled by a broken-off railing from the churchyard. No culprit could be found for his murder." "Mon Dieu!" "And then there was Sir Basil Spile, whose body was found in 1890 at the foot of Great Gable in the Lake District. He appeared to have fallen, but since he was not a rambler or climber, and was wearing full evening dress and dancing pumps without a mark on them, again, no-one could explain what happened. There was also Miss Drusilla Dunholme, the heiress to a tobacco fortune, whose decapitated body - " "Mam'selle, please! No more! Colonel Moriarty was responsible for all this?" "And more, Marie, according to Mr Holmes." My little maid sat down on my bed, pale and with a hand to her heart. I sat down beside her. "You need not come with me, you know, Marie," I said. "Mam'selle, must you go to where this evil man is?" "Yes, Marie. I can't rest while Lord Bywell is apart from me. He's in more danger than you or I." "Mam'selle, if I may say so, you are very much in love with his lordship. Would it not be more sensible to keep out of danger yourself?" "You've answered the question, Marie. I'm very much in love with his lordship. It's different from when I was with Mr Holmes. He could easily look after both himself and me, but Stephen - Lord Bywell - isn't used to these escapades." "But he is a very brave man, mam'selle. He is also strong and a great athlete." "Of course he is. But he's not a good shot with a pistol and that's why I want to be with him, or at least near him at this time." Marie smiled. "Very well, Mam'selle Anna, and I am coming with you." "Come then," I said. "Let's try on these breeches and jerseys. I fancy that you will wish to make a few last-minute alterations." Later that sunny evening, with our breeches concealed by skirts, stout boots on our feet, and our pistols securely belted on, Marie and I took charge of the horse and trap I had hired. The groom looked doubtfully at us as we climbed aboard. "Ye sure ye can manage this, missus?" "Oh, I think so, thank you," I answered. "Aye, ye've drove afore, hevn't ye?" he continued, cocking an approving eye at the way I gathered the reins. "The mare's quiet enyeuf, and used ter strangers drivin'. The road's aall reet gannin' up, but ye'll need ter use the brake comin' back, or ye's'll both be oot on the groond. An' then we'll hev ter bring ye's both yem on a shutter. So tak my advice an' divvent gan ower far. There's aboot two hours o' daylight left." With that he sent us on our way. The mare responded first time to my "Walk on" and we clattered away. "Mam'selle," said Marie once we were out of earshot, "what was he talking about? I could not understand a word, and I thought I was doing so well with the Cockneys. But here it is worse than the speech of the Vosges." I repeated the groom's warning about the road. When I first went north with Stephen I, too, could not understand a word of the local speech, but by now I was getting used to it. We trotted briskly along the country roads with the sinking sun behind us warming our backs pleasantly. We could still hear the crack of guns from the direction of Stephen's estate, but as we trotted on it gave way to a distant flat rapping, a repeated pressure on our eardrums, that told us of another shoot some distance across the quiet fields. The Times had said that the Colonel was shooting with one Sir Michael Elliott, and an enquiry at a farmhouse set us on the road. At length we began the climb to Broomley, with the guns growing louder in our ears. By then there was "aboot" an hour and a half of daylight, and the shoot was still blazing away. Reaching a stand of trees near the deserted road, we stopped, took off our skirts and jackets and donned our warm jerseys and ear-flapped travelling caps which we had in a small basket. The guns were at some distance on the other side of the trees. I checked my ivory-handled Webley, my well-appreciated gift from Annie Oakley which had saved my life - and Mycroft's - more than once. "Have you loaded your pistol, Marie?" "Yes, mam'selle." "I shall have to train you with a revolver, but your derringer will do to defend yourself. Now, let's walk through this stand of trees and perhaps we shall see Colonel Moriarty." The trees, it turned out, were an end of a long wood. As we cautiously made our way through them, we could see the beaters at work some hundred yards away. It would be the last beat of the day, and a small covey of game birds flurried out into the line of guns as we watched. We were too far away to make out faces, but I had no doubt that the tall fellow at the end of the line was Colonel Moriarty. As I looked, he downed a brace with both barrels. "He's good," I began to say, when a voice cut in. "Aall reet, the two o' ye's. Aa've got a gun on ye's, so divvent dee nowt rash!" Even in the deepening shade of the trees, Marie's face was as white as I'm sure mine was. If she didn't understand the language, she understood the tone. Slowly we turned and looked into the double barrel of a twelve bore gun. Holding it was a grim-faced, wiry man, with a lad beside him. The very threads of their tweeds proclaimed "gamekeepers". The lad had a nasty-looking dog on the end of a short leash. "Haway. Oot o' this." The pair of them swiftly ushered us through the trees, the dog sniffing in an unpleasant way at our legs. As we emerged into the dying sunlight, the two men registered astonishment. "Why, ye - ye're women!" "How interesting," said a new voice. Silhouetted in the low sun was a figure whose face I could not make out, no matter how much I screwed up my eyes. "Miss Anna Weybridge, I believe. We haven't been formally introduced, although I have had the pleasure of waiting on you, as it were." Lighting a cigarette, he moved casually out of the sun. "Colonel James Moriarty at your service. This will be your maid and companion, Mademoiselle Saverne. Very well, Barker. Miss Weybridge and Mademoiselle will come with me. They have left a trap on the road. Richard, you can go and drive it back to the Duke of Wellington. Tell them Miss Weybridge has accepted an invitation to stay with Sir Michael. Take this money to pay the bill. See that the ladies' things are packed and sent across. Leave the dog with Mr Barker. Oh, and if the ladies have left any belongings in the trap, make sure you bring them back with you." He gave these instructions in the cool manner of one who is never disobeyed. The boy Richard ran down to the road, while Mr Barker, carrying his shotgun under one arm, began to escort us down a field path away from the direction of the shooting party. The dog sniffed at the backs of our knees the whole time, and for my own part I was too frightened to say anything. Marie stumbled along beside me. We boarded a waggonette standing in a farm track. Barker drove and the dog ran behind. The Colonel sat opposite us placidly smoking cigarettes and contemplating us with those little sideways movements of his head. Marie and I held hands to try to control our trembling, but not a word was spoken throughout our drive, which took us along the track to a house set among trees well away from the road. The unfortunate Miss Drusilla Dunholme filled my thoughts. Since we were both armed, we should have drawn our pistols, but Marie was trembling so much that I don't think she could have held her pistol steadily, or even safely. I was managing hardly better self-control, and the trouble was that Colonel Moriarty sat the whole time with Barker's shotgun across his knee. Now I have said before in these jottings of mine that on occasion I've drawn and fired without even being aware of it. But I had foolishly strapped on my waist-belt so that the holster was behind me under my jersey, and I was sitting on the pistol. Not only was it fearfully uncomfortable, but to have drawn and covered the Colonel before he brought up his shotgun would have been impossible. Even if I could have done it, I could not commit murder. I had killed men, once in self-defence and once to save Mycroft, but I could not do it in cold blood, to say nothing of the fact that I should hang for it. We alighted at the front door in the glow of the setting sun, and were ushered inside by Colonel Moriarty, with the dreadful dog still sniffing about our legs until we were over the threshold. I kept a grip on the comfort of Marie's hand as the Colonel bowed us politely into the drawing room where the lamps had already been lit. Waiting to greet us was the very tall man from the shooting party, whom I had mistaken for Moriarty himself. "Sir Michael Elliott," said the Colonel. "Miss Anna Weybridge. Mademoiselle Saverne." Sir Michael took my hand and bent over it. To Marie he gave a curt bow. He had sandy hair and a sunburned complexion, a well-trimmed moustache underlining a firm nose, and a monocle which gave an unnatural gleam to one eye. "Shall I have Mademoiselle shown to the servants' hall?" asked Moriarty. "No," replied Sir Michael. "She may as well hear what we have to say to her mistress. What the - ?" He might well exclaim. As Moriarty no longer had his shotgun, I found the courage to act decisively. Hoisting up my jersey behind me, I drew my revolver and covered Sir Michael. Beside him, the Colonel goggled. "By George! Can you use that thing, Miss Weybridge?" "Yes, Colonel. I can shoot quite straight." Sir Michael and the Colonel looked at one another and broke into guffaws. "A woman of spirit!" said Sir Michael. "You never told me this about her, Moriarty. And the maid too, by God!" For Marie drew her derringer, cocked it and pointed it unsteadily, first at Sir Michael, then at the Colonel. "Sir Michael," I said, my voice quivering, "the Colonel has brought us to you by force - " "I protest!" said the Colonel. "I did no such thing. Mademoiselle, would you mind relaxing the pressure of your finger on the trigger? That looks like a .41 calibre, and at this distance it will make a considerably bigger hole in me than Miss Weybridge's .32 Webley will make in Sir Michael." "It would be better, ladies, if you put away your pistols," said Sir Michael. "I can assure you that we intend no harm to you. At any time, you may leave this house and return to the Duke of Wellington. I should be sorry, however, if you chose to do so. But I beg that Mademoiselle at least puts away her pistol. Her hand seems a little unsteady and I don't wish to lose my friend here." Remembering how Marie had fortunately but inadvertently shot Karl-Gustav Grüner, I nodded to her. But Marie was trembling so much that as she lowered her gun, she fired into the rich Turkey carpet, between the very feet of the Colonel. Moriarty didn't flinch. Instead, he looked solemnly at Marie, who seemed unable to move, and said, "Now see what you've done." In rushed Barker with his shotgun, and after him the butler holding the striker of the dinner gong. Whether he had been about to use it or had merely snatched it up as a weapon, I could not say, but at the sight Sir Michael laughed again. "Thank you, Beresford, we do not need you. We are in no danger, Barker. The carpet has suffered a mishap, but I can assure you that these ladies mean us no harm, despite appearances." In the hallway a large looking-glass hung on the wall. Reflected in the glass was a third man, a well-built man with a revolver, who was standing out of my direct line of sight. I noticed that his nose was slightly twisted as though he had suffered an accident in boxing or rugby. Sir Michael stepped up to this man, patted his arm and said something in a low voice. He returned, closed the door and asked us to sit down. Marie was so white that I thought she would faint, but she managed to sink into a chair, the Colonel putting her pistol into her pocket for her, as I re-holstered mine. "Mademoiselle, a little brandy?" said Sir Michael. "Moriarty, would you mind? It's over there. Napoleon is invaluable in times of strain. Miss Weybridge, would you care to join Mademoiselle? No? A little wine, then? I fear our meeting has not gone as I hoped." He was all affability, serving Moriarty, Marie and himself, for I refused everything. I was half afraid that he might try to drug us both, but Marie rallied and the colour returned to her cheeks. Moriarty lit a cigar at a lamp while Sir Michael pulled up a chair. "I have a serious topic to discuss with you, Miss Weybridge." "I did not think you had brought us here to invite us shooting, Sir Michael." "Miss Weybridge, you and Mademoiselle are very level-headed." "Devilish cool hands," added Moriarty at the lamp, "if you'll excuse my language. I'm not altogether sure that Mademoiselle's shooting trick was an accident, eh, Elliott?" "Colonel," I said, "don't try to flatter us. You brought us here against our will. Now please let us go." "My dear ladies," said Sir Michael, "as I said, you are free to leave here at any time. Unfortunately, I have no means of transporting you back to Riding Mill. This house is isolated and it's a long walk across country. If you glance through the window you'll see how dark the night has become. It's clouded over, although I think the rain will keep off, but I must warn you that there are a few desperate characters who tend to be out and about at night between here and Riding Mill." "Armed ladies with cool heads won't worry about cut-throats," said Moriarty, blowing a smoke ring. "I'd be worried," said Sir Michael. "If someone crept up behind me with a length of piano wire and garrotted me, what good would a revolver be? And if the odds were two against one, why, what chance would I have? Or you, Moriarty? And as for two young ladies, no matter how courageous - and they're pretty courageous, you'll agree - could they stand up to ruffians with wires?" "Wires and knives," said Moriarty cheerfully. "And dogs," added Sir Michael. "Lurchers, bull terriers and so on." "What do they do with the bodies?" asked the Colonel. "Oh, I'm told there are plenty of places in the woods where no-one ever finds them," replied Sir Michael. "Thank you, gentlemen," I said sharply. "We understand your drift." "A sensible lady, Miss Weybridge," said Moriarty. "The reason why we brought you here," said Sir Michael, "although you are free to leave at any time, was to put to you a proposition that we thought might interest you." "It's finance, mind," said the Colonel. "High finance involving lots of money." "Some of which will come your way," said Sir Michael. "And your way too, Mademoiselle Saverne. I'm sure Miss Weybridge is a generous employer, but could even the most generous employer pay her lady's maid a salary of a thousand a year? A young woman with that income could marry her intended as quickly as she pleased." "And did the stage ever pay five thousand a year?" asked the Colonel, smiling at me. "I know that Miss Terry and Sir Henry must be earning close on that or even more, but they are exceptions." "The ladies must be wondering what we have in mind, Colonel. Would you broach the topic?" The Colonel poured himself a drink first. I sat tight-lipped. I was sure Marie shared my feelings about these two. The irony was that, although we were both armed, we were powerless. There were others in the house who would come in at a call from Sir Michael. I had no doubt that someone was listening at the door and that any attempt by us to leave would be either stopped or, worse, followed. I was certain that the threats were real, and that henchmen were stationed along the dark route where we would have to walk back home. Moriarty sat down again and leaned forward, a hand on each knee, his glass on an occasional table beside him. "Miss Weybridge, I shall not try to conceal the fact that for some weeks I have been watching your movements. I know about the Difference Engine and what it will be able to do once it's built." "Colonel," I interrupted, "I know nothing about the Difference Engine, except that it's to be built. How it works, I do not know." "Very well, Miss Weybridge. But I myself have a good knowledge of its principles, for it has never been a secret, and you need not fear that we intend to try to force non-existent knowledge from you. Given the money, Sir Michael and I could build a Difference Engine of our own. Given the money, I say. But since we have not the money, and the Government has, we turn to you." He outlined their plan. Marie and I were to act as spies against the man I loved so as to enable Moriarty and Sir Michael to use the Difference Engine secretly. I was now convinced that Moriarty had been behind the burglary because he was unable to find a copy of the plans in libraries and needed Stephen's to study. "There will be times," said Sir Michael, "when the Difference Engine will be unguarded. All we need to know, Miss Weybridge, is when we can gain access to it. You need not involve yourself directly. You could send Mademoiselle as if on some legitimate errand - " "Comment?" gasped Marie. " - or send some other messenger. The important thing is that we get unhindered to the machine for a few hours per week, by night preferably." "Why?" I was almost bursting with indignation. Sir Michael smiled. "We know that we can use the machine for calculations that will be useful to us - yes, Beresford?" The butler had hurriedly entered. "A gentleman has called, sir. He sent in this card and said you would know what it meant." Sir Michael studied the card, turned it over and read something, then looked sharply at Moriarty as he handed it to him. I saw the handwriting and my heart soared. "Dear me," said the Colonel. "I didn't count on his coming here." "He gives me no choice but to see him," said Sir Michael. "Carry on with the explanation, Colonel. I'll see him in my study." Mycroft pushed in past the butler. In all my life I was never so relieved to see his massive figure as then. One hand in his coat pocket, he immediately placed himself between the Colonel and me. Barker and his shotgun came in after him. "Really, Mr Holmes," said Moriarty coolly, "there is no need for this melodramatic intrusion." "Thank you, Barker," said Sir Michael. "We are still in no danger. Thank you, Beresford. You may go." A door clashed and the man with the crooked nose appeared for an instant in the passageway mirror before Barker blocked my view by leaving the room. "Now, Mr Holmes," said Sir Michael. "I trust you have an explanation for what the Colonel quite rightly calls a melodramatic mode of entry." "My explanation is sitting opposite you," answered Mycroft. "These two ladies, I believe, were carried here against their will." His face darkened and he gazed at the carpet, sniffed the air, and glanced at Marie and then at me. "Your carpet tells me that a shot has been fired in here. The powder smudge on Marie's right hand is the penalty of using a short-barrelled pistol. Unfortunately, the Colonel's cigar masks the smell of powder. Why did you fire, Marie?" "It was an accident, sir. My hand was trembling because I was frightened. Mr 'Olmes, I am so afraid. Please help us." "You had already drawn your pistol? And Miss Weybridge?" "Mam'selle had drawn hers, but she did not fire." Mycroft directed a stern glare at Sir Michael and Moriarty. "I should like to speak to you both privately, gentlemen." Sir Michael nodded and led the Colonel and Mycroft to a door, at the same time touching the button of an electric bell. "You will not object, Mr Holmes, to one of my servants waiting on the ladies while we are out of the room." Beresford came in, rather to my relief, for the surly Barker would have been unbearable. The butler stood impassive, blocking the doorway as the three men went out by the other door into what I imagined was the study. For several minutes Marie and I sat in silence until Sir Michael re-entered looking red and angry. "Ladies, you will find a trap and driver waiting at the front door. You need not fear. The driver has been engaged by Mr Holmes. It has been a pleasure meeting you. Good night." Our initial astonishment yielded to an overwhelming urge to get out of the house as quickly as we could. The butler gravely showed us to the door. The man with the bent nose had disappeared, and outside, a trap was ready with a driver muffled up against the night. Surprisingly, he made no move to help us up, so Beresford handed us both into the vehicle, which immediately set off. Only after we had got clear of the house did the driver say over his shoulder, "The amount of hot water you get into, Anna, would fill the pump room at Harrogate." "Beefy!" "Lord Bywell thinks I'm safely tucked up in bed with a queasy stomach. I'll say nothing to him about this evening's events, of course, and I advise you to do the same. Holmes wishes you to make an immediate journey to Norfolk. Your trunks are already at the station, and you'll almost certainly be followed by Moriarty if you don't get out of this district quickly. There's a train to Newcastle in twenty-five minutes, and your connection is the sleeper to King's Cross. However, you must break your journey at Peterborough and take the first train into Norfolk. Put up anywhere on the coast, Holmes says, wire him, and don't go home until Lord Bywell's there. We think your flat will be watched. Don't forget to let Watson know so that he can redirect any letters." We drove from the track onto the road and Beefy whipped up the horse. "I'm taking fearful risks at this speed when I can hardly see a dashed thing, but I'm afraid we'll be followed." Marie and I seized each other's hands and began to cast nervous glances behind us as we jolted on. It was more frightening than one of Mycroft's hansom rides, and I tried to take my mind off our onward rush between high hedgerows and under dark trees. "What's Mycroft doing here?" "Same as you, only more expertly. Honestly, Anna, you do get yourself into scrapes. Why couldn't you just have left it all to us?" "Because the man I love is here, and in some danger! If you were a woman you'd understand. Ah! Look out!" as we careered round a tight bend and Marie and I clutched each other and shrieked. "Whoops! That raised the old hair. Well, I must confess I did have the dickens of a job to stop Jo from coming here with me. Just as well, because she'd have been in the thick of it with you two, even in her present condition." "Did Mycroft know we were in Northumberland?" "Of course he did! He deduced it all when he spotted Watson leaving your flat this morning with some letters in his hand. Since Watson locked the door behind him, it was clear the flat was empty. There was only one place you would be, knowing you as we both do, so Holmes decided to join Bywell and me. He didn't make his concern about you known to Bywell, but he told me in a coded wire. Once he'd got here this evening, Holmes made enquiries locally and soon found your digs. He went round to try to make you go home, and found you'd gone off in a trap and the people at the inn were getting worried about you. He took this trap himself, called at the back door of Bywell Manor for me, told me to fob off Bywell with some excuse, and we got here as fast as we could." "How did he know we were with Sir Michael?" "The groom at the Wellington told him about you being 'invited' to Sir Michael's place. They'd sent one of their lads off in a dog cart with your luggage, so we overhauled him and redirected it to the station. The rest was easy. Oh, by the way, that basket under your seat has your skirts and things in it that you left in your trap." We hadn't even thought about the scandal of appearing on a station platform in our breeches and stockings. We opened the basket, not without a struggle in the buffeting trap, and took out our garments as Beefy pulled up. "We're on the outskirts of the village of Stocksfield. There's a farm track here. Walk along it. Don't be afraid. When you reach a gate barring your way, in about a hundred yards, feel for a stile on your right. Head across the field for the station lights and climb the fence. You will then cross the railway line to the end of the platform. Wait in the shadows until the train comes in and board it unobtrusively. Here is some money. You must travel third class. At Newcastle Central Station enquire for the sleeper to King's Cross. You won't need your skirts yet. Too many fences to climb. Good luck." Even as we swung down from the trap, Beefy turned it then whipped up the horse and rattled off, leaving us carrying our skirts and jackets over our arms. Something bounced and grated on the road as he drove off. "There's the basket!" he called as he vanished into the darkness. Sighing, Marie and I picked it up, put our skirts and jackets into it and began to trudge along the deep darkness of the farm track. At length we found the gate and the stile and plodded across the field in the direction of the station lights. Still carrying our basket, we climbed the fence, crossed the track, put on our skirts over our breeches, and hid in the shadows till the train came in. A noisy little crowd of countrywomen alighted, coming home late from market, and we mingled with them and hastily entered their third class carriage. Looking carefully out, I noticed a man further along the platform peering into the first class carriages. The whistle blew, we moved off, and as we rose from hurriedly ducking down, we observed Moriarty gazing after the train. "Mon Dieu, mam'selle!" whispered Marie. "These men, they move quickly, non?"