| Paralysis produced by ticks bites.

/

Paralisis producida por picadura de garrapatas.

DATA-MEDICOS

DERMAGIC/EXPRESS 19-(201)

24 Noviembre 2.017 24 November 2.017

EDITORIAL ENGLISH

=================

Hello friends of the network today DERMAGIC EXPRESS brings you

another interesting and hot topic, once again about the TICKS

and the diseases that are capable of transmitting to the human

being, it is the TICK PARALYSIS (TP), produced by the

bite of some TICKS, which transmit a

NEUROTOXIN which produces

PARALYSIS in some parts of your body, even causing

death in 10 to 12% of cases.

The TICK PARALYSIS, is now considered a

ENVENOMING NEUROTOXIC which is similar to polio,

affects both children and adults (majority children) especially

in regions considered

HYPERENDEMIC as the

West of the United States and the regions of

Eastern Australia.

Historically, the Australians Hamilton Hume and William Hove

described the first bites of TICKS TO HUMANS in 1.824, but

it was Bancroft in 1.884 the first to report two cases

(2) of toxicosis by TICKS TO HUMANS describing 2

cases with weakness and blurred vision.

The first death was reported by Cleland in 1,912.

Since that time the disease has been reported almost everywhere

in the world.

This disease is considered a rare condition, but very well

studied by our scientists, and begins with the transmission

of a

NEUROTOXIN that is in the salivary glands of the

FEMALE ticks that when feed with blood enter to the bloodstream

causing the symptoms which are characterized by A

ASCENDING FLACCID PARALYSIS of the muscles that

begins 2 to 7 days after the bite, in the lower limbs, and then

goes up to the trunk, arms, head and death can occur due to

respiratory failure. Other symptoms include numbness,

decreased tendon reflexes, ophthalmoplegia, and bulbar palsy.

THE TICK PARALYSIS (TP) can be misdiagnosed, and

confuse medical science with entities such as: ACUTE ATAXIA,

TRANSVERSE MYELITIS, EPIDURAL ABSCESS, BOTULISM AND

GULLAIN BARRE SYNDROME (GBS), the latter being the

one that lends itself most to confusion.

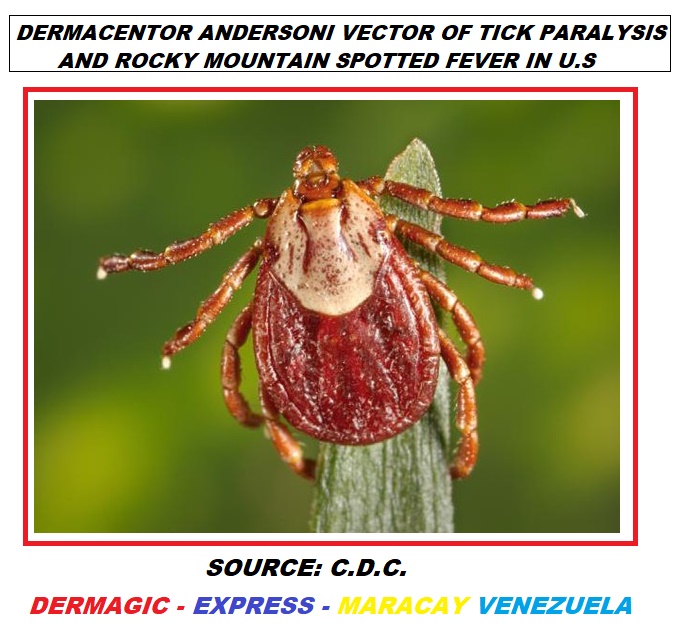

The causative agents of this condition are fully identified:

In the United States of America, the vector is the

TICK DERMACENTOR ANDERSONI, which also transmits

the

DISEASE THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS SPOTTED FEVER. Another

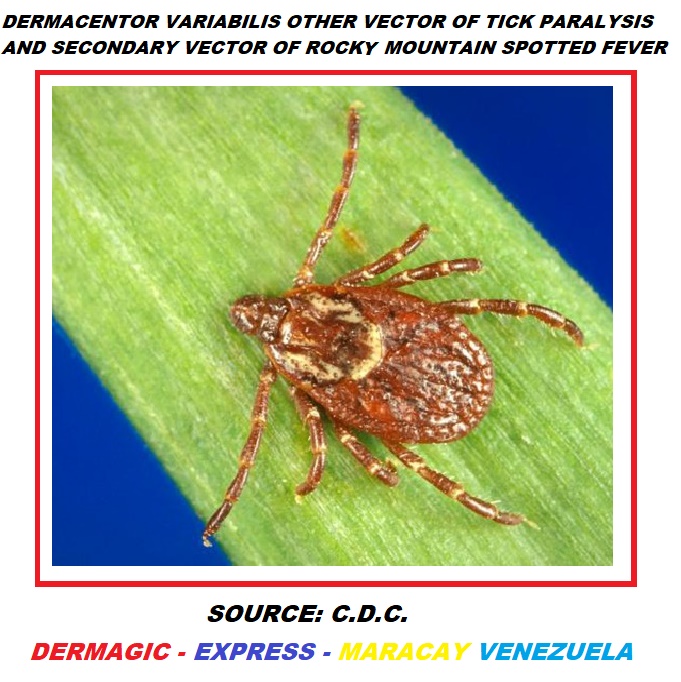

causative agent of this disease is the

TICK DERMACENTOR VARIABILIS, considered the

second most frequent vector in the transmission of THE ROCKY

MOUNTAINS SPOTTED FEVER.

But this does not stop here; Approximately

69 species of TICKS from all over the world are able to

induce PARALYSIS BY BITTING. In other countries, such as the

southeast of

AUSTRALIA, this disease (TP) is also endemic

and the causative agents are other TICKS, among which the

TICK of the

IXODES genus, IXODES HOLOCYCLUS, and

IXODES CORNUATUS, also

DERMACENTOR ANDESONI and

VARIABILIS

stand out.

In South Africa the most important vector is the

TICK IXODES RUBICUNDUS,

in ETHIOPIA, the

TICKS RHIPICEPHALUS EVERTSI EVERTIS and

ARGAS WALKERAE and

TICK ARGAS RADIATUS in the

Neartic region of North America.

The disease considered as a

global extension "SUPPOSEDLY" has not been described in

the HEMISPHERE SUR, but in the year 1.994, two (2) cases

were described in

ARGENTINA in the province of Jujuy. A case (1) was

also described on the Pacific coast of

MEXICO, produced by the TICK

AMBLYOMA MACULATUM. It has also been reported in

THE BRITISH COLUMBIA, the third most populated province of

CANADA, 57 cases between 1.993 and 2.016 being the

most common vector the TICK DERMACENTOR ANDERSONI, the cases

were found in both humans and animals.

TICKS PARALYSIS has also been described in animals such as:

cats, dogs, cattle horses, sheep, and birds, being

the

TICK IXODES HOLOCYCLUS the most involved. In fact,

today this disease in Australia is considered a veterinary

problem because of the large number of infected animals, and the

main host of this is the mammal

LONG-NOSED-BANDICOOT.

Unlike other diseases such as LYME, POWASSAN and HEARTLAND

DISEASE, where the TICK involved TRANSMITS a bacterium (LYME)

or virus (POWASSAN and HEARTLAND) that infects the organism,

in the case of TICK PARALYSIS (TP) it is a

NEUROTOXIN that only remains in the organism

WHILE THE TICK IS ADHERED TO THE SKIN FEEDING WITH BLOOD,

when taking it off the symptoms gradually disappear recovering

the patient, even though the

LETHALITY is of 10 -12%. So that...

I describe another disease TRANSMITTED BY TICKS, and I leave you

the same reflection of my other reviews, the best way to

AVOID THEM, is not only to fight

for human rights to receive adequate treatment

LIKE THE CASE OF LYME DISEASE, which have been

Violated in many countries, especially in the US, we also have

to fight against

VECTORS and

HOSTS.

Greetings to all

Dr. José Lapenta

EDITORIAL ESPAÑOL

=================

Hola amigos de la red hoy DERMAGIC EXPRESS te trae otro tema

bien interesante y caliente, una vez más sobre las

GARRAPATAS y las enfermedades que son capaces de

transmitir al humano, se trata de la PARALISIS POR

GARRAPATAS, producida por la picadura de unas

GARRAPATAS, las cuales transmiten una

NEUROTOXINA la cual produce

PARALISIS en ciertas partes de tu organismo

incluso pudiendo causar la

muerte en un 10 a 12%

de los casos.

La PARALISIS POR MORDEDURA DE GARRAPATAS, es considerada

hoy día un

ENVENENAMIENTO NEUROTOXICO la cual es similar

al polio, afecta tanto niños como adultos (mayormente a

niños) especialmente en regiones consideradas

HIPERENDEMICAS como el

Oeste de los Estados Unidos y las regiones del

Este de Australia.

Históricamente los Australianos Hamilton Hume y William

Hove describieron las primeras mordeduras de GARRAPATAS

A HUMANOS en 1.824,

pero fue Bancroft en 1.884 el primero en reportar dos

casos (2) de toxicosis por GARRAPATAS A HUMANOS

describiendo 2 casos con debilidad y visión Borrosa.

La primera muerte fu reportada por Cleland en 1,912.

Desde esa época la enfermedad ha sido reportada en casi todo

el mundo.

Esta enfermedad es considerada una rara condición, pero muy

bien estudiada por nuestros científicos, y comienza por

la transmisión de una

NEUROTOXINA que está en las glándulas salivales de

las garrapatas HEMBRAS que al alimentarse de sangre

pasan al torrente sanguíneo ocasionando los síntomas los

cuales están caracterizados por

UNA PARALISIS FLACIDA de los músculos

ASCENDENTE que comienza 2 a 7 días después de

la picadura, en los miembros inferiores, y luego sube al

troco, brazos, cabeza y puede ocurrir la muerte por fallo

respiratorio. Otros síntomas incluyen, obnubilación,

disminución de los reflejos tendinosos, oftalmoplegia y

parálisis bulbar.

LA PARALISIS POR GARRAPATAS (TP) puede ser

diagnosticada erróneamente, y confundir a la ciencia médica

con entidades como: ATAXIA AGUDA, MIELITIS TRANSVERSA,

ABSCESO EPIDURAL, BOTULISMO Y

SINDROME DE GULLAIN BARRE (GBS), siendo este

ultimo el que se presta más a confusión.

Los agentes causales de esta condición están totalmente

identificados: En los Estados Unidos de Norteamérica el

vector es la

GARRAPATA DERMACENTOR ANDERSONI, la cual

también es transmisora de

LA ENFERMEDAD FIEBRE MOTEADA DE LAS MONTAÑAS ROCOSAS.

Otro agente causal de esta enfermedad es la

GARRAPATA DERMACENTOR VARIABILIS, considerado el

segundo vector más frecuente en la transmisión DE LA

FIEBRE MOTEADA DE LAS MONTAÑAS ROCOSAS.

Pero esto no queda aquí, Aproximadamente

69 especies de garrapatas de todo el mundo son

capaces de inducir LA PARALISIS POR MORDEDURA DE GARRAPATA.

En otros países como el sureste de

AUSTRALIA, esta enfermedad (TP) también es

endémica y los agentes causales son otras GARAPATAS

entre las que destacan principalmente la

GARAPATA

del genero IXODES,

IXODES HOLOCYCLUS, e

IXODES CORNUATUS, también

DERMACENTOR ANDESONI y

VARIABILIS.

En

SUDAFRICA el vector más importante es

LA GARRAPATA IXODES RUBICUNDUS, en

ETIOPIA, las

GARRAPATAS RHIPICEPHALUS EVERTSI EVERTIS y

ARGAS WALKERAE y la

GARRAPATA ARGAS RADIATUS en la

región Neartica de América del Norte.

La enfermedad considerada de

extensión mundial "SUPUESTAMENTE" no ha

sido descrita en el HEMISFERIO SUR, pero en él año 1.994

fueron descritos dos (2) caso en

ARGENTINA en la provincia de Jujuy. También

fue descrito un caso (1) en la costa del pacifico

MEXICANA producido por la

GARRAPATA AMBLYOMA MACULATUM. También ha sido

reportada en LA COLUMBIA BRITANICA, tercera provincia

más poblada de

CANADA, 57 casos entre 1.993 Y 2.016 siendo el

vector mas común la GARRAPATA

DERMACENTOR ANDERSONI, los caso fueron

hallados tanto en humanos como animales.

La PARALISIS POR GARRAPATAS también ha sido descrita en

animales como:

gatos perros, ganado caballos, ovejas, y pájaros,

siendo la GARRAPATA

IXODES HOLOCYCLUS la mas involucrada. De hecho

hoy día esta enfermedad en Australia es considerada un

problema veterinario por la gran cantidad de animales

infectados, y el huesped principal de esta garrapata en

AUSTRALIA es el mamifero marsupial

"BANDICOOT DE NARIZ LARGA"

A diferencia de otras enfermedades como LA ENFERMEDAD DE

LYME, POWASSAN y HEARTLAND donde LA GARRAPATA involucrada

TRANSMITE una bacteria (LYME) o virus (POWASSAN y

HEARTLAND) que infecta el organismo, en el caso de la

PARALISIS POR GARRAPATA (TP) es una

NEUROTOXINA

que solo permanece en el organismo MIENTRAS LA

GARRAPATA ESTA

ADHERIDA A LA PIEL ALIMENTANDOSE CON SANGRE,

al despegarla los síntomas paulatinamente desaparecen

recuperándose el paciente, aun así la

LETALIDAD es del 10 -12%. De modo que...

Te describo hoy otra enfermedad TRANSMITIDAD POR GARRAPATAS,

y te dejo la misma reflexión de mis otras revisiones, la

mejor manera de EVITARLAS NO ES SOLO luchar por los

derechos humanos a recibir tratamiento adecuado

COMO EL CASO DE

LA ENFERMEDAD DE LYME, los cuales han sido

violentados en muchos países, especialmente en US, también

hay que luchar contra los

VECTORES y

HUESPEDES.

Saludos a Todos

Dr. José Lapenta.

=============================================================================

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES /

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRAFICAS

=============================================================================

1.) A Retrospective Cohort Study of Tick Paralysis in British

Columbia.

2.) A Comparative Meta-Analysis of Tick Paralysis in the United

States and Australia.

3.) A 60-year meta-analysis of tick paralysis in the United States:

a predictable, preventable, and often misdiagnosed poisoning.

4.) Tick paralysis.

5.) Tick paralysis cases in Argentina.

6.) Neurotoxin-induced paralysis: a case of tick paralysis in a 2-year-old

child.

7.) Tick paralysis presenting in an urban environment.

8.) Tick paralysis: 33 human cases in Washington State, 1946-1996.

9.) Cluster of tick paralysis cases--Colorado, 2006.

10.) The association between landscape and climate and reported tick

paralysis cases in dogs and cats in Australia.

11.) Delineation of an endemic tick paralysis zone in southeastern

Australia.

12.) A list of the 70 species of Australian ticks; diagnostic guides

to and species accounts of Ixodes holocyclus (paralysis tick),

Ixodes cornuatus (southern paralysis tick) and Rhipicephalus

australis (Australian cattle tick); and consideration of the place

of Australia in the evolution of ticks with comments on four

controversial ideas.

13.) Tick paralysis caused by Amblyomma maculatum on the Mexican

Pacific Coast.

14.) Tick Paralysis — Washington, 1995

15.) Rare Cause of Facial Palsy: Case Report of Tick Paralysis by

Ixodes Holocyclus Imported by a

Patient Travelling into Singapore from Australia.

16.) A Comparative Meta-Analysis of Tick Paralysis in the United

States and Australia.

17.) Tick paralysis in Australia caused by Ixodes holocyclus Neumann

=================================================================

=================================================================

1.) A Retrospective Cohort Study of Tick Paralysis in British

Columbia.

=================================================================

Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017 Oct 30. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2017.2168.

[Epub ahead of print]

Morshed M1,2, Li L1,2, Lee MK1, Fernando K1, Lo T1, Wong Q1.

Author information

1

1 Zoonotic Diseases and Emerging Pathogens Section, BC Centre of

Disease Control Public Health Laboratory , Vancouver, Canada .

2

2 Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of

British Columbia , Vancouver, Canada .

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Tick paralysis is a frequently overlooked severe disease

characterized by bilateral ascending flaccid paralysis caused by a

neurotoxin produced by feeding ticks. We aimed to characterize

suspected tick paralysis cases documented at the BC Centre for

Disease Control (BCCDC) in British Columbia (BC) from 1993 to 2016

and reviewed prevention, diagnosis, and treatment considerations.

METHODS:

Demographic, geographic, and clinical data from test requisition

forms for ticks submitted to the BCCDC Public Health Laboratory (PHL)

from patients across BC between 1993 and 2016 for suspected human

and animal tick paralysis were reviewed. Descriptive statistics were

generated to characterize tick paralysis cases in BC, including tick

species implicated, seasonality of disease, and regional differences.

RESULTS:

From 1993 to 2016, there were 56 cases of suspected tick paralysis

with at least one tick specimen submitted for testing at the BCCDC

PHL. Humans and animals were involved in 43% and 57% of cases,

respectively. The majority of cases involved a Dermacentor andersoni

tick (48 cases or 86%) and occurred between the months of April and

June (49 cases or 88%). Among known locations of tick acquisition,

the Interior region of BC was disproportionately affected, with 25

cases (69%) of tick bites occurring in that area.

CONCLUSIONS:

Tick paralysis is a rare condition in BC. The region of highest risk

is the Interior, particularly during the spring and summer months.

Increasing awareness of tick paralysis among healthcare workers and

the general public is paramount to preventing morbidity and

mortality from this rare disease.

===========================================================================

2.) A Comparative Meta-Analysis of Tick Paralysis in the United

States and Australia.

==========================================================================

Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015 Nov;53(9):874-83. doi:

10.3109/15563650.2015.1085999. Epub 2015 Sep 11.

Diaz JH1.

Author information

1

a Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of

Public Health , 2020 Gravier Street, New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

United States.

Abstract

CONTEXT:

Tick paralysis is a neurotoxic envenoming that mimics polio and

primarily afflicts children, especially in hyperendemic regions of

the Western United States of America (US) and Eastern Australia.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the epidemiology, clinical and electrodiagnostic

manifestations, and outcomes of tick paralysis in the US versus

Australia.

METHODS:

A comparative meta-analysis of the scientific literature was

conducted using Internet search engines to identify confirmed cases

of tick paralysis in the US and Australia. Continuous variables

including age, time to tick removal, and duration of paralysis were

analyzed for statistically significant differences by unpaired

t-tests; and categorical variables including gender, regional

distribution, tick vector, tick attachment site, and misdiagnosis

were compared for statistically significant differences by chi-square

or Fisher exact tests.

RESULTS:

Tick paralysis following ixodid tick bites occurred seasonally and

sporadically in individuals and in more clusters of children than in

adults of both sexes in urban and rural locations in North America

and Australia. The case fatality rate for tick paralysis was low,

and the proportion of misdiagnoses of tick paralysis as Guillain-Barré

syndrome (GBS) was greater in the US than in Australia. Although

electrodiagnostic manifestations were similar, the neurotoxidromes

differed significantly with prolonged weakness and even residual

neuromuscular paralysis following tick removal in Australian cases

compared with US cases.

DISCUSSION:

Tick paralysis was a potentially lethal envenoming that occurred in

children and adults in a seasonally and regionally predictable

fashion. Tick paralysis was increasingly misdiagnosed as GBS during

more recent reporting periods in the US. Such misdiagnoses often

directed unnecessary therapies including central venous

plasmapheresis with intravenous immunoglobulin G that delayed

correct diagnosis and tick removal.

CONCLUSION:

Tick paralysis should be added to and quickly excluded from the

differential diagnoses of acute ataxia with ascending flaccid

paralysis, especially in children living in tick paralysis-endemic

regions worldwide.

===========================================================================

3.) A 60-year meta-analysis of tick paralysis in the United States:

a predictable, preventable, and often misdiagnosed poisoning.

==========================================================================

J Med Toxicol. 2010 Mar;6(1):15-21. doi: 10.1007/s13181-010-0028-3.

Diaz JH1.

Author information

1

LSU School of Public Health, New Orleans, LA, USA. [email protected]

Abstract

Tick paralysis (TP) is a neurotoxic poisoning primarily afflicting

young girls in endemic regions. Recent case series of TP have

described increasing misdiagnoses of TP as the Guillain-Barré

syndrome (GBS). A meta-analysis of the scientific literature was

conducted using Internet search engines to assess the evolving

epidemiology of TP. Fifty well-documented cases of TP were analyzed

over the period 1946-2006. Cases were stratified by demographics,

clinical manifestations, and outcomes. Misdiagnoses were subjected

to Yates-corrected chi-square analyses to detect statistically

significant differences in proportions of misdiagnoses between

earlier and later reporting periods. TP occurred seasonally and

sporadically in individuals and in clusters of children and adults

of both sexes in urban and rural locations. The case fatality rate (CFR)

for TP was 6.0% over 60 years. The proportion of misdiagnoses of TP

as GBS was significantly greater (chi(2) = 7.850, P = 0.005) in more

recently collected series of TP cases, 1992-2006, than the

proportion of misdiagnoses in earlier series, 1946-1996. TP was a

potentially lethal poisoning that occurred in children and adults in

a seasonally and regionally predictable fashion. TP was increasingly

misdiagnosed as GBS during more recent reporting periods. Such

misdiagnoses often directed unnecessary therapies such as central

venous plasmapheresis with intravenous immunoglobulin G, delayed

correct diagnosis, and tick removal, and could have increased CFRs.

TP should be added to and quickly excluded from the differential

diagnoses of acute ataxia and ascending flaccid paralysis,

especially in children living in TP-endemic regions of the USA.

==========================================================================

4.) Tick paralysis.

=========================================================================

Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008 Sep;22(3):397-413, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.03.005.

Edlow JA1, McGillicuddy DC.

Author information

1

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, West Clinical Center 2, One

Deaconess Road, West Campus - CC 2, Boston, MA 02215, USA. [email protected]

Abstract

The one tick-borne disease that rarely comes under the auspices of

the infectious disease specialist is not caused by an infectious

agent, but is tick paralysis. This condition is caused by tick bite

and typically presents as a flaccid ascending paralysis. This

article discusses this entity partly because of completeness, but

also because tick paralysis, or tick toxicosis as it is sometimes

called, is worth the infectious disease consultant's consideration.

The differential diagnosis includes entities that are infectious or

caused by toxins of infectious agents, such as epidural abscess,

some causes of transverse myelitis, and botulism. Lastly, in an era

of antibiotic toxicity, multidrug-resistant bacteria, antigen-switching

viruses, and complex antibiotic regimens, the cure for tick

paralysis-removing the tick-is as simple as it is gratifying.

==========================================================================

5.) Tick paralysis cases in Argentina.

==========================================================================

Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012 Jul-Aug;45(4):533-4.

Remondegui C1.

Author information

1

Servicio de Infectologia y Medicina Tropical, Hospital San Roque,

Ministerio de Salud de la Provincia de Jujuy, Jujuy, Argentina.

[email protected]

Abstract

Tick paralysis (TP) occurs worldwide and is caused by a neurotoxin

secreted by engorged female ticks that affects the peripheral and

central nervous system. The clinical manifestations range from mild

or nonspecific symptoms to manifestations similar to Guillain-Barré

syndrome, bulbar involvement, and death in 10% of the patients. The

diagnosis of TP is clinical. To our knowledge, there are no formal

reports of TP in humans in South America, although clusters of TP

among hunting dogs in Argentina have been identified recently. In

this paper, clinical features of two cases of TP occurring during

1994 in Jujuy Province, Argentina, are described.

==========================================================================

6.) Neurotoxin-induced paralysis: a case of tick paralysis in a 2-year-old

child.

==========================================================================

Pediatr Neurol. 2014 Jun;50(6):605-7. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.01.041.

Epub 2014 Jan 24.

Taraschenko OD1, Powers KM2.

Author information

1

Department of Neurology, Albany Medical College, Albany, New York.

Electronic address: [email protected].

2

Department of Neurology, Albany Medical College, Albany, New York.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Tick paralysis is an arthropod-transmitted disease causing

potentially lethal progressive ascending weakness. The presenting

symptoms of tick paralysis overlap those of acute inflammatory

diseases of the peripheral nervous system and spinal cord; thus, the

condition is often misdiagnosed, leading to unnecessary treatments

and prolonged hospitalization.

PATIENT:

A 2-year-old girl residing in northern New York and having no

history of travel to areas endemic to ticks presented with rapidly

progressing ascending paralysis, hyporeflexia, and intact sensory

examination. Investigation included blood and serum toxicology

screens, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and brain imaging. With all

tests negative, the child's condition was initially mistaken for

botulism; however, an engorged tick was later found attached to the

head skin. Following tick removal, the patient's weakness promptly

improved with no additional interventions.

CONCLUSION:

Our patient illustrates the importance of thorough skin examination

in all cases of acute progressive weakness and the necessity to

include tick paralysis in the differential diagnosis of paralysis,

even in nonendemic areas.

==========================================================================

7.) Tick paralysis presenting in an urban environment.

==========================================================================

Pediatr Neurol. 2004 Feb;30(2):122-4.

Gordon BM1, Giza CC.

Author information

1

Department of Pediatrics, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los

Angeles, California 90095, USA.

Abstract

We report the case of a 17-month-old female with tick paralysis

presenting to an urban Los Angeles emergency department. The tick

was later identified as the North American wood tick, Dermacentor

andersoni, and was likely obtained while the family was vacationing

on a dude ranch in Montana. We discuss the epidemiology of tick

paralysis, a differential diagnosis for health care providers, and

methods of detection and removal. Given the increasing popularity of

outdoor activities and ease of travel, tick paralysis should be

considered in cases of acute or subacute weakness, even in an urban

setting.

==========================================================================

8.) Tick paralysis: 33 human cases in Washington State, 1946-1996.

==========================================================================

Clin Infect Dis. 1999 Dec;29(6):1435-9.

Dworkin MS1, Shoemaker PC, Anderson DE.

Author information

1

Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV, STD, and

TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta,

GA 30333, USA. [email protected].

Abstract

Tick paralysis is a preventable cause of illness and death that,

when diagnosed promptly, requires simple, low-cost intervention (tick

removal). We reviewed information on cases of tick paralysis that

were reported to the Washington State Department of Health (Seattle)

during 1946-1996. Thirty-three cases of tick paralysis were

identified, including 2 in children who died. Most of the patients

were female (76%), and most cases (82%) occurred in children aged <8

years. Nearly all cases with information on site of probable

exposure indicated exposure east of the Cascade Mountains. Onset of

illness occurred from March 14 to June 22. Of the 28 patients for

whom information regarding hospitalization was available, 54% were

hospitalized. Dermacentor andersoni was consistently identified when

information on the tick species was reported. This large series of

cases of tick paralysis demonstrates the predictable epidemiology of

this disease. Improving health care provider awareness of tick

paralysis could help limit morbidity and mortality due to this

disease.

==========================================================================

9.) Cluster of tick paralysis cases--Colorado, 2006.

==========================================================================

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006 Sep 1;55(34):933-5.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Abstract

Tick paralysis is a rare disease characterized by acute, ascending,

flaccid paralysis that is often confused with other acute neurologic

disorders or diseases (e.g., Guillain-Barré syndrome or botulism).

Tick paralysis is thought to be caused by a toxin in tick saliva;

the paralysis usually resolves within 24 hours after tick removal.

During May 26-31, 2006, the Colorado Department of Public Health and

Environment received reports of four recent cases of tick paralysis.

The four patients lived (or had visited someone) within 20 miles of

each other in the mountains of north central Colorado. This report

summarizes the four cases and emphasizes the need to increase

awareness of tick paralysis among health-care providers and persons

in tick-infested areas.

==========================================================================

10.) The association between landscape and climate and reported tick

paralysis cases in dogs and cats in Australia.

==========================================================================

Vet Parasitol. 2014 Aug 29;204(3-4):339-45. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.05.018.

Epub 2014 May 17.

Brazier I1, Kelman M2, Ward MP3.

Author information

1

The University of Sydney, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Camden

2570, NSW, Australia.

2

Virbac Australia, Milperra 1891, NSW, Australia.

3

The University of Sydney, Faculty of Veterinary Science, Camden

2570, NSW, Australia. Electronic address: [email protected].

Abstract

The aim of this study was to describe the association between

landscape and climate factors and the occurrence of tick paralysis

cases in dogs and cats reported by veterinarians in Australia. Data

were collated based on postcode of residence of the animal and the

corresponding landscape (landcover and elevation) and climate (precipitation,

temperature) information was derived. During the study period (October

2010-December 2012), a total of 5560 cases (4235 [76%] canine and

1325 [24%] feline cases) were reported from 341 postcodes, mostly

along the eastern seaboard of Australia and from the states of New

South Wales and Queensland. Significantly more cases were reported

from postcodes which contained areas of broadleaved, evergreen tree

coverage (P=0.0019); broadleaved, deciduous open tree coverage

(P=0.0416); and water bodies (P=0.0394). Significantly fewer tick

paralysis cases were reported from postcodes which contained areas

of sparse herbaceous or sparse shrub coverage (P=0.0297) and areas

that were cultivated and managed (P=0.0005). No significant

(P=0.6998) correlation between number of tick paralysis cases

reported per postcode and elevation was found. Strong positive

correlations were found between number of cases reported per

postcode and the annual minimum (rSP=0.9552, P<0.0001) and maximum (rSP=0.9075;

P=0.0001) precipitation. Correlations between reported tick

paralysis cases and temperature variables were much weaker than for

precipitation, rSP<0.23. For maximum temperature, the strongest

correlation between cases was found in winter (rSP=0.1877; P=0.0005)

and for minimum temperature in autumn (rSP=0.2289: P<0.0001). Study

findings suggest that tick paralysis cases are more likely to occur

and be reported in certain eco-climatic zones, such as those with

higher rainfall and containing tree cover and areas of water.

Veterinarians and pet owners in these zones should be particularly

alert for tick paralysis cases to maximize the benefits of early

treatment, and to be vigilant to use chemical prophylaxis to reduce

the risk of tick parasitism.

==========================================================================

11.) Delineation of an endemic tick paralysis zone in southeastern

Australia.

==========================================================================

Vet Parasitol. 2017 Nov 30;247:42-48. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.09.005.

Epub 2017 Sep 6.

Whitfield Z1, Kelman M2, Ward MP3.

Author information

1

Sydney School of Veterinary Science, The University of Sydney,

Camden NSW, Australia.

2

Kelman Scientific, Peregian Beach QLD, Australia.

3

Sydney School of Veterinary Science, The University of Sydney,

Camden NSW, Australia. Electronic address: [email protected].

Abstract

Tick paralysis has a major impact on pet dog and cat populations in

southeastern Australia. It results from envenomation by Ixodes

holocyclus and Ixodes cornuatus ticks, the role of Ixodes cornuatus

in the epidemiology of this disease in Australia being unclear. The

aim of this study was to describe the geographical distribution of

tick paralysis cases in southeastern Australia using data from a

national disease surveillance system and to compare characteristics

of "endemic" cases with those reported outside this endemic zone ("sporadic"

cases). Data were collated and a proportional symbol map of all

cases by postcode was created. A 15-case isopleth was developed

based on descriptive spatial statistics (directional ellipses) and

then kernel smoothing to distinguish endemic from sporadic cases.

During the study period (January 2010-December 2015) 12,421 cases

were reported, and 10,839 of these reported by clinics located in

434 postcodes were included in the study. Endemic cases were

predominantly reported from postcodes in coastal southeastern

Australia, from southern Queensland to eastern Victoria. Of those

cases meeting selection criteria, within the endemic zone 10,767

cases were reported from 351 (88%) postcodes and outside this zone

72 cases were reported from 48 (12%) postcodes. Of these latter 48

postcodes, 18 were in Victoria (26 cases), 16 in New South Wales (28

cases), 7 in Tasmania (9 cases), 5 in South Australia (7 cases) and

2 in Queensland (2 cases). Seasonal distribution in reporting was

found: 62% of endemic and 52% of sporadic cases were reported in

spring. The number of both endemic and sporadic cases reported

peaked in October and November, but importantly a secondary peak in

reporting of sporadic cases in April was found. In non-endemic areas,

summer was the lowest risk season whilst in endemic areas, autumn

was the lowest risk season. Two clusters of sporadic cases were

identified, one in South Australia (P=0.022) during the period 22

May to 2 June 2012 and another in New South Wales (P=0.059) during

the period 9 October to 29 November 2012. Endemic and sporadic cases

did not differ with respect to neuter status (P=0.188), sex

(P=0.205), case outcome (P=0.367) or method of diagnosis (P=0.413).

However, sporadic cases were 4.2-times more likely to be dogs than

cats (P<0.001). The endemic tick paralysis zone described is

consistent with previous anecdotal reports. Sporadic cases reported

outside this zone might be due to a history of pet travel to endemic

areas, small foci of I. holocyclus outside of the endemic zone, or

in the case of southern areas, tick paralysis caused by I. cornuatus.

==========================================================================

12.) A list of the 70 species of Australian ticks; diagnostic guides

to and species accounts of Ixodes holocyclus (paralysis tick),

Ixodes cornuatus (southern paralysis tick) and Rhipicephalus

australis (Australian cattle tick); and consideration of the place

of Australia in the evolution of ticks with comments on four

controversial ideas.

==========================================================================

Barker SC1, Walker AR2, Campelo D3.

Author information

1

Department of Parasitology, School of Chemistry and Molecular

Biosciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072,

Australia. Electronic address: [email protected].

2

Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh,

EH25 9RG Scotland, United Kingdom.

3

Department of Parasitology, School of Chemistry and Molecular

Biosciences, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Qld 4072,

Australia.

Abstract

Seventy species of ticks are known from Australia: 14 soft ticks (family

Argasidae) and 56 hard ticks (family Ixodidae). Sixteen of the 70

ticks in Australia may feed on humans and domestic animals (Barker

and Walker 2014). The other 54 species of ticks in Australia feed

only on wild mammals, reptiles and birds. At least 12 of the species

of ticks in Australian also occur in Papua New Guinea. We use an

image-matching system much like the image-matching systems of field

guides to birds and flowers to identify Ixodes holocyclus (paralysis

tick), Ixodes cornuatus (southern paralysis tick) and Rhipicephalus

(Boophilus) australis (Australian cattle tick). Our species accounts

have reviews of the literature on I. holocyclus (paralysis tick)

from the first paper on the biology of an Australian tick by

Bancroft (1884), on paralysis of dogs by I. holocyclus, to papers

published recently, and of I. cornuatus (southern paralysis tick)

and Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) australis (Australian cattle tick). We

comment on four controversial questions in the evolutionary biology

of ticks: (i) were labyrinthodont amphibians in Australia in the

Devonian the first hosts of soft, hard and nuttalliellid ticks?; (ii)

are the nuttalliellid ticks the sister-group to the hard ticks or

the soft ticks?; (iii) is Nuttalliella namaqua the missing link

between the soft and hard ticks?; and (iv) the evidence for a

lineage of large bodied parasitiform mites (ticks plus the

holothyrid mites plus the opiliocarid mites).

=============================================================================

13.) Tick paralysis caused by Amblyomma maculatum on the Mexican

Pacific Coast.

=============================================================================

Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011 Jul;11(7):945-6. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0154.

Epub 2011 Mar 11.

Espinoza-Gomez F1, Newton-Sanchez O, Flores-Cazares G, De la

Cruz-Ruiz M, Melnikov V, Austria-Tejeda J, Rojas-Larios F.

Author information

1

Communicable Disease Group, Faculty of Medicine, University of

Colima, Colima, Mexico.

Abstract

Tick paralysis is a rare entity in which it is necessary to identify

the cause and remove the arthropod to have a rapid remission of

symptoms. In the absence of an early diagnosis, the outcome can be

fatal, as toxins are released from the tick's saliva as it feeds. To

the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first clinical

report of the disease in Mexico and Latin America. A 22-year-old man

from a rural area, who was in contact with cattle, developed

ascending flaccid paralysis secondary to Amblyomma maculatum tick

toxin. He presented flaccid paraplegia and arreflexia that

progressed until causing dyspnea. The clinical symptoms subsided 48

h after the ticks spontaneously detached. The ticks were discovered

by nursing personnel while the patient was being transferred to a

regional hospital with the diagnosis of Guillain-Barré syndrome. The

patient was asymptomatic on discharge from hospital and showed no

further motor deterioration at a 1-month follow-up.

=============================================================================

14.) Tick Paralysis — Washington, 1995

============================================================================

Tick Paralysis — Continued Tick paralysis (tick toxicosis)—one of

the eight most common tickborne diseases in

the United States (1 )—is an acute, ascending, flaccid motor

paralysis that can be confused

with Guillain-Barré syndrome, botulism, and myasthenia gravis. This

report

summarizes the results of the investigation of a case of tick

paralysis in Washington.

On April 10, 1995, a 2-year-old girl who resided in Asotin County,

Washington, was

taken to the emergency department of a regional hospital because of

a 2-day history

of unsteady gait, difficulty standing, and reluctance to walk. Other

than a recent history

of cough, she had been healthy and had not been injured. On physical

examination,

she was afebrile, alert, and active but could stand only briefly

before requiring

assistance. Cranial nerve function was intact. However, she

exhibited marked extremity

and mild truncal ataxia, and deep tendon reflexes were absent. She

was admitted

with a tentative diagnosis of either Guillain-Barré syndrome or

postinfectious

polyradiculopathy.

Within several hours of hospitalization, she had onset of drooling

and tachypnea. A

nurse incidentally detected an engorged tick on the girl’s hairline

by an ear and removed

the tick. Within 7 hours after tick removal, tachypnea subsided and

reflexes

were present but diminished. The patient recovered fully and was

discharged on

April 11. The tick species was not identified.

Reported by: E Haas, D Anderson, R Neu, Asotin County Health Dept,

Clarkston, Washington.

N Berkheiser, MD, Saint Joseph Regional Medical Center, Lewiston,

Idaho. J Grendon, DVM,

P Shoemaker, J Kobayashi, MD, P Stehr-Green, DrPH, State

Epidemiologist, Washington State

Dept of Health. Div of Field Epidemiology, Epidemiology Program

Office, CDC.

Editorial Note: Tick paralysis occurs worldwide and is caused by the

introduction of a

neurotoxin elaborated into humans during attachment of and feeding

by the female of

several tick species. In North America, tick paralysis occurs most

commonly in the

Rocky Mountain and northwestern regions of the United States and in

western Canada.

Most cases have been reported among girls aged <10 years during

April–June,

when nymphs and mature wood ticks are most prevalent (2 ). Although

tick paralysis

is a reportable disease in Washington, surveillance is passive, and

only 10 cases were

reported during 1987–1995.

In the United States, this disease is associated with Dermacentor

andersoni (Rocky

Mountain wood tick), D. variabilis (American dog tick), Amblyomma

americanum

(Lone Star tick), A. maculatum, Ixodes scapularis (black-legged tick),

and I. pacificus

April 26, 1996 / Vol. 45 / No. 16

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES / Public Health Service

325 Tick Paralysis — Washington, 1995

326 Update: Influenza Activity —

United States and Worldwide,

1995–96 Season, and Composition

of the 1996–97 Influenza Vaccine

330 Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis

Outbreak on an HIV Ward —

Madrid, Spain, 1991–1995

333 Adult Blood Lead Epidemiology

and Surveillance — United States,

Fourth Quarter, 1995

335 Notice to Readers

(western black-legged tick) (3,4 ). Onset of symptoms usually occurs

after a tick has

fed for several days. The pathogenesis of tick paralysis has not

been fully elucidated,

and pathologic and clinical effects vary depending on the tick

species (4 ). However,

motor neurons probably are affected by the toxin, which diminishes

release of acetylcholine

(5 ). In addition, experimental studies indicate that the toxin may

produce a

substantial decrease in maximal motor-nerve conduction velocities

while simultaneously

increasing the stimulating current potential necessary to elicit a

response (5 ).

If unrecognized, tick paralysis can progress to respiratory failure

and may be fatal

in approximately 10% of cases (6 ). Prompt removal of the feeding

tick usually is followed

by complete recovery. Ticks can be attached to the scalp or neck and

concealed

by hair and can be removed using forceps or tweezers to grasp the

tick as closely as

possible to the point of attachment (7 ). Removal requires the

application of even pressure

to avoid breaking off the body and leaving the mouth parts imbedded

in the host.

Gloves should be worn if a tick must be removed by hand; hands

should be promptly

washed with soap and hot water after removal of a tick.

The risk for tick paralysis may be greatest for children in rural

areas, especially in

the Northwest, during the spring and may be reduced by the use of

repellants on skin

and permethrin-containing acaricides on clothing. Paralysis can be

prevented by careful

examination of potentially exposed persons for ticks and prompt

removal of ticks.

Health-care providers should consider tick paralysis in persons who

reside or have

recently visited tick-endemic areas during the spring or early

summer and who present

with symmetrical paralysis.

References

1. Spach DH, Liles WC, Campbell GL, Quick RE, Anderson DE, Fritsche

TR. Tick-borne diseases

in the United States. N Engl J Med 1993;329:936–47.

2. CDC. Tick paralysis—Wisconsin. MMWR 1981;30:217–8.

3. CDC. Tick paralysis—Georgia. MMWR 1977;26:311.

4. Gothe R, Kunze K, Hoogstraal H. The mechanisms of pathogenicity

in the tick paralyses. J Med

Entomol 1979;16:357–69.

5. Kocan AA. Tick paralysis. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988;192:1498–500.

6. Schmitt N, Bowmer EJ, Gregson JD. Tick paralysis in British

Columbia. Can Med Assoc

J 1969;100:417–21.

7. Needham GR. Evaluation of five popular methods for tick removal.

Pediatrics 1985;75:9

=============================================================================

15.) Rare Cause of Facial Palsy: Case Report of Tick Paralysis by

Ixodes Holocyclus Imported by a

Patient Travelling into Singapore from Australia.

=============================================================================

J Emerg Med. 2016 Nov;51(5):e109-e114. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.02.031.

Epub 2016 Sep 9.

Pek CH1, Cheong CS2, Yap YL1, Doggett S3, Lim TC1, Ong WC1, Lim J1.

Author information

1

Division of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery,

Department of Surgery, National University Health System, Singapore.

2

Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery, National

University Health System, Singapore.

3

Department of Medical Entomology, Pathology West, Westmead Hospital,

Westmead, NSW, Australia.

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Ticks are blood-sucking arachnids that feed on all classes of

vertebrates, including humans. Ixodes holocyclus, also known as the

Australian Paralysis Tick, is capable of causing a myriad of

clinical issues in humans and companion animals, including the

transmission of infectious agents, toxin-mediated paralysis,

allergic and inflammatory reactions, and mammalian meat allergies in

humans. The Australian Paralysis Tick is endemic to Australia, and

only two other exported cases have been reported in the literature.

CASE REPORT:

We report the third exported case of tick paralysis caused by I.

holocyclus, which was imported on a patient into Singapore. We also

discuss the clinical course of the patient, the salient points of

management, and the proper removal of this tick species. WHY SHOULD

AN EMERGENCY PHYSICIAN BE AWARE OF THIS?: With increasing air travel,

emergency physicians need to be aware of and to identify imported

cases of tick paralysis to institute proper management and advice to

the patient. We also describe the tick identification features and

proper method of removal of this tick species.

============================================================================

16.) A Comparative Meta-Analysis of Tick Paralysis in the United

States and Australia.

==================================================================

Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015 Nov;53(9):874-83. doi:

10.3109/15563650.2015.1085999. Epub 2015 Sep 11.

Diaz JH1.

Author information

1

a Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, School of

Public Health , 2020 Gravier Street, New Orleans, Louisiana 70112

United States.

Abstract

CONTEXT:

Tick paralysis is a neurotoxic envenoming that mimics polio and

primarily afflicts children, especially in hyperendemic regions of

the Western United States of America (US) and Eastern Australia.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the epidemiology, clinical and electrodiagnostic

manifestations, and outcomes of tick paralysis in the US versus

Australia.

METHODS:

A comparative meta-analysis of the scientific literature was

conducted using Internet search engines to identify confirmed cases

of tick paralysis in the US and Australia. Continuous variables

including age, time to tick removal, and duration of paralysis were

analyzed for statistically significant differences by unpaired

t-tests; and categorical variables including gender, regional

distribution, tick vector, tick attachment site, and misdiagnosis

were compared for statistically significant differences by chi-square

or Fisher exact tests.

RESULTS:

Tick paralysis following ixodid tick bites occurred seasonally and

sporadically in individuals and in more clusters of children than in

adults of both sexes in urban and rural locations in North America

and Australia. The case fatality rate for tick paralysis was low,

and the proportion of misdiagnoses of tick paralysis as Guillain-Barré

syndrome (GBS) was greater in the US than in Australia. Although

electrodiagnostic manifestations were similar, the neurotoxidromes

differed significantly with prolonged weakness and even residual

neuromuscular paralysis following tick removal in Australian cases

compared with US cases.

DISCUSSION:

Tick paralysis was a potentially lethal envenoming that occurred in

children and adults in a seasonally and regionally predictable

fashion. Tick paralysis was increasingly misdiagnosed as GBS during

more recent reporting periods in the US. Such misdiagnoses often

directed unnecessary therapies including central venous

plasmapheresis with intravenous immunoglobulin G that delayed

correct diagnosis and tick removal.

CONCLUSION:

Tick paralysis should be added to and quickly excluded from the

differential diagnoses of acute ataxia with ascending flaccid

paralysis, especially in children living in tick paralysis-endemic

regions worldwide.

============================================================================

17.) Tick paralysis in Australia caused by Ixodes holocyclus Neumann

============================================================================

Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2011 Mar;105(2):95-106. doi:

10.1179/136485911X12899838413628

S Hall-Mendelin,* S B Craig,†‡ R A Hall,* P O’Donoghue,* R B Atwell,§

S M Tulsiani,† and G C Graham

Author information

1

School of Chemistry and Molecular Biosciences, University of

Queensland, St Lucia, Australia. [email protected]

Abstract

Ticks are obligate haematophagous ectoparasites of various animals,

including humans, and are abundant in temperate and tropical zones

around the world. They are the most important vectors for the

pathogens causing disease in livestock and second only to mosquitoes

as vectors of pathogens causing human disease. Ticks are formidable arachnids, capable of not only transmitting the pathogens involved

in some infectious diseases but also of inducing allergies and

causing toxicoses and paralysis, with possible fatal outcomes for

the host. This review focuses on tick paralysis, the role of the

Australian paralysis tick Ixodes holocyclus, and the role of toxin

molecules from this species in causing paralysis in the host.

Many forms of tick toxicosis affect humans and other animals (Gothe

and Neitz, 1991; Mans et al., 2004). According to Gothe (1984), a

tick toxicosis is defined as a ‘generalized, experimentally

standardizable, reproducible disease syndrome induced by one or a

few potent ticks, even on first infestation of a physiological

susceptible vertebrate species without participation of an

immunopathological reaction during or following the tick feeding’.

Such toxicoses are mostly caused by ixodid or hard ticks (Stone and

Wright, 1981) and, in their most severe form, result in paralysis of

the infested host. About 69 species of ticks from around the world

are capable of inducing paralysis (Gothe and Neitz, 1991), the most

important being Ixodes holocyclus in Australia, Dermacentor

andersoni, De. variabilis and Argas (Persicargas) radiatus in North

America, Ix. rubicundus in South Africa, Rhipicephalus evertsi

evertsi and Ar. (Pers.) walkerae in Ethiopia, and Ar. (Pers.)

radiatus in the Nearctic region of North America (Stone, 1986). Some

important paralysing ticks and their distributions are summarized in

Table 1. In Australia, Ix. holocyclus can cause paralysis in humans,

dogs, cats, sheep, cattle, goats, pigs and horses but predominantly

infests dogs, cats and humans (Stone, 1986). It appears to be the

most potently toxic tick species, with a single tick capable of

killing a large dog (Stone and Wright, 1981) or sheep (Sloan, 1968).

Although the Tasmanian paralysis tick Ix. cornuatus has been

reported to cause bulbar paresis and respiratory failure in humans (Tibballs

and Cooper, 1986) and dogs (Beveridge et al., 2004), its habitat is

more restricted than that of Ix. holocyclus and very few cases of

paralysis have been associated with this tick. In Australia, tick

paralysis has mainly been seen as a problem in veterinary medicine,

affecting approximately 10,000 companion animals/year (Stone and

Aylward, 1987). Occasionally, however, the climatic conditions

become particularly favorable to tick survival, tick densities reach

very high levels, and the number of humans being bitten by Ix.

holocyclus increases. Although rarely severe, tick paralysis caused

by Ix. holocyclus can be fatal

===================================================================

DATA-MEDICOS/DERMAGIC-EXPRESS No 19-(201) 24/11/2.017 DR. JOSE

LAPENTA R.

===================================================================

Produced

by Dr. Jose Lapenta R. Dermatologist 2.017

Maracay Estado Aragua Venezuela 2.017

Telf: 0416-6401045- 02432327287-02432328571

loading...

|