CHARNUS |

- 24TH FEBRUARY 2021

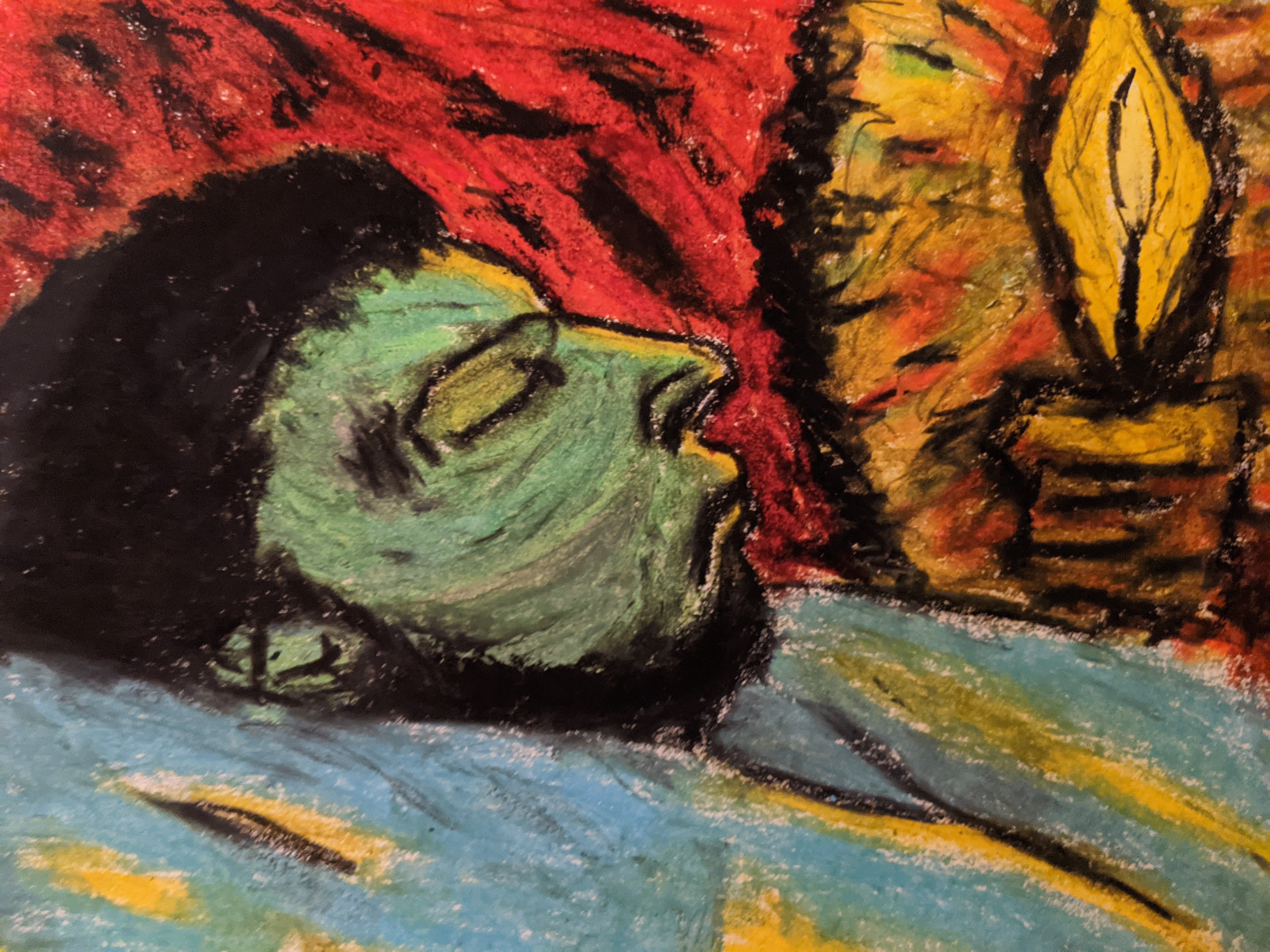

The wind and storm did not let up for very long, however, and, going to bed that night, the windows began to rattle again as the fires burnt out downstairs. The excited thoughts of the afternoon and evening before continued into the night and were what kept me awake, at least initially. As the firelight once again gave up the fight to the blackening, dirty clouds of dark and cold in my room, so too did the aching sensations of mind and body return. Weighed down by blankets and darkening thoughts, even the energy required to toss-and-turn was lost.

I thought how naïve I had been earlier that day; had I really believed that I had found the ultimate answer needed to assuage my feelings of guilt and inadequacy about my life? No, I had not taken a stand or valiantly fought for a particular cause, I had, merely, delegated that decision to someone else. And, in doing this, I had, merely, prevaricated again; I had neither succumbed to my fear of death in return for a hope of a better time in the next life as the servants of the Beast had nor had I defeated it by putting my faith in something heart-whole and striving for its ideals. No, the fear that had resurfaced from my childhood had not been destroyed, just forgotten and momentarily buried under some half-baked plot of human design. And this was little different from how I had, for years, acquiesced to the government’s decision-making. And now, many still viewed the official narratives of a solitary fight uncritically and were happy to let people be killed in the name of their defence.

In the days that followed, my thoughts remained fairly constant in their occupation on this theme. The day of action was coming closer now and my involvement was irrevocable; I was drawn into its orbit and it fascinated and excited me. But I also knew that I must find something else before it was all over and finished. These couple of weeks would be dramatic, I was certain, and my fate would be decided by the time of their conclusion. But my thoughts would not cohere in my mind and I had no idea which way I would go. Maybe I would even betray Husayn and Mary and become a quietist citizen of this unrecognisable country? I couldn’t quite tell. Every now and then, I felt flashes of an urge to submit to the almost irresistible and charismatic evil of the Beast just as I had once, in childhood fear and awe of the power I attributed to Him, made bargains with the Devil in my head. My ability to focus on what I was reading also vanished and I gave up searching for answers in books. Among the jumble of thoughts and projections cast from my disordered mind, I could barely even decipher the words on the page.

The weather remained dreary throughout that first week of my visitors’ sojourn in an unfamiliar land. We spent most of the time together, talking, listening to music, and braving the rain most days for long walks on the moors and in the forests. We did discuss the plan sometimes but, increasingly, rarely, and I became less and less interested in that day in the future, with its details and aims. In my mind, it was decided, what we were going to do had been planned and must happen. Instead, my thoughts were drawn inwards to my internal struggles, beliefs and emotions and backwards to previous times of introspection. Interaction with others further exacerbated this looking back to past lives, regrets and failed ambitions. As I said, we also listened to more music which triggered these instances of recollection.

Beyond that, however, we loved hearing songs of resistance and righteous anger, of struggle against a seemingly unconquerable leviathan fuelled by a certain belief that right will prevail and that this evil Beast will be defeated. In those days, the music I am thinking of encompassed Reggae, the songs of the U.S. Civil Rights movement, Irish revolutionaries and wartime internationalists like Paul Robeson. These were songs of past oppressed peoples and, shamelessly relating them to our present personal struggles, we all identified with them.

Keeping our minds off of what was coming, we were discussing music while out chopping logs when Husayn proffered: “It was all rebel music wasn’t it really back then in the ‘70s. Well, not all of it obviously, but the kind of stuff we remember: Reggae; Soul; Funk; Afrobeat; all that kind of stuff. It’s what lifted the burden of oppression a bit after Civil Rights splintered and racism continued. What allowed them to keep the struggling going and not succumb to it. My grandfather – the other one, from Pakistan – he was working in factories in the ‘60s and ‘70s with all these guys from West Africa and the Caribbean and they all listened to the music coming out of Jamaica and America and Nigeria. And a lot of them were Black Panthers and so was my grandfather; there was more solidarity then between all of the immigrants and the people who were marginalised at the time. Obviously, racism by the police and the trade unions was a lot worse than it is now and so they needed that really. They needed that solidarity and defiance more.

“But when I look now at what’s happened to that, I can’t really believe it. These people whose parents and grandparents came to this country and fought for the right for a place in society are now backing the xenophobia. Even before the pandemic. Loads of my relatives hate the idea of Africans coming over here. And my grandfather, he was in with the Black Panthers, helped organise them and went to the meetings and the protests. But I never knew him like that. They all got splintered with Thatcher and the war on the unions. My grandfather got obsessed with buying his own council house and saved all his money, kept his head down and didn’t get into any trouble for years. And told his children and his wife they just had to work and study and couldn’t go to the cinema and they couldn’t afford the school trips and they couldn’t enjoy themselves. By the time I was born, he had already bought his house and all his children had moved out but he still lived the same way. He was such an old skinflint; there was nothing on the walls hardly and he’d always be on at my grandmother not to go to this or that shop because it was too expensive or “Turn off that water now! You think we’re made of money!?” when the bath had been running apparently too long. And he never changed, all us grandkids would get a bar of chocolate for our birthdays and that was it. We knew he had money but he was just putting it in the bank.

“And then, when he died, everyone was happy about it. I felt bad but it was just so good that this miserly tyrant had gone and wouldn’t be there to criticise our every decision. We had a great big party after he died – after the funeral – and my grandmother must’ve spent half his money on it. He never enjoyed it and was buried in some cheap suit he’d had for thirty-odd years. But then the pandemic came not long after and soon enough there were these petty tyrants everywhere. People had so little to think about, only their own concerns and needs, they were all worrying and shouting about the silliest things. And looking forward to some tiny little pleasure which consumed their whole minds. We all became even more isolated and individualistic and everyone was spending all their money ordering stuff online and there was no solidarity with the people who were delivering it or working in the warehouses. Everyone knew what their conditions were like and that they were still working and risking their own health and couldn’t even enjoy their time off properly. And everyone knew the companies were getting richer at the same time and for what? Those few extra billions weren’t making the bosses any happier while a servant underclass was growing up isolated and cut-off from the rest of society. From those with whom they should’ve made common cause. And the billions weren’t going back into the economy either, just into vanity projects and investment funds.” His speech by this point had quickened and was at its most febrile and acerbic. Even though we had heard these arguments before – even witnessed and been aware of the same events elsewhere – such a change had been effected on his usually gentle face that we did not doubt the apparent profundity of his commentary. But, just at that moment, his voice faltered and died. A more disturbing change occurred as his expression became one of crushed excitement and dashed hope.

He paused momentarily and the swinging motion of the axe – which had continued throughout his speech – stopped for the first time. “No,” he said “we didn’t enjoy things for very long after my grandfather died. Suddenly, he didn’t seem so bad anymore.”

We were all of us then quiet for a while, standing motionless in the woods and are arms holding axes only limply. I reconnected with the feeling of a few days ago that I was on the verge of wresting myself out of an ironical slumber and could, in my own small way, commit to an action that may help to undermine the present state of things. Rather than being depressed by the reminder of how neoliberalism had gone from bad to worse in our time, my mind was transfixed by the idea that now could be the time for things to change. Since the pandemic had started, very few real events had actually occurred. In fact, the mundanity, inaction and closetedness of life had only increased. Perhaps now the tiniest act could disrupt the whole paradigm underpinning the status quo and release unlimited possibilities once again, I thought? Out of the quiet, quiescent life of these woods, a new chain of events could be triggered that would revivify the beauty of life, of nature, of the birds and lichen and flowers in this forest. And make people want to go out and appreciate this now rather than succumbing to their fears, deferring life and change until later. And not blindly extracting every moment of happiness from the slavery and misery of their fellow humans.

Here we were, I thought, three very different people who, until recently, knew nothing of one another, banding together despite our differences in the belief that we could do something. And hoping and praying that our action and sacrifice meant taking a stand against fear and blind faith in tawdry dogmas and twisting political spin and slippery narratives. And, whatever we believed in or used as our guidebook along this pilgrimage, we could still work together to achieve something better than this. I was still seeking a personal response to my understanding of metaphysical questions but did not doubt the urgency and the basic ethical rightness of this rebellion. Putting aside one’s own desires and plans to combat the violent superstructure compelling us into division. That mysterious force alien to humanity which forces the strong to surrender to a pointless oppression of the weak, corrupting both groups in the process.

My ideas slowly transmuting more into abstract passions than cogent thoughts, the silence was interrupted then by Mary. A complete non sequitur, at least to me, she asked: “What’s been your route here then Ebenezer?” She always seemed to relish pronouncing my name what with its literary associations, vaguely biblical and Nonconformist sound, and the ease with which it could be pronounced with a strong Westcountry-rhotic ending. “How did you get this huge house and why did you choose to come and live out here?”

Taken aback and defenceless in my surprise at being asked this question which, I soon realised, I should have foreseen, I immediately attempted to construct a glib justification for my position: “Well, I had a relative – a distant kind of uncle, I think – who lived out here for years as a kind of hermit. Not any kind of anchorite or monk or anything you might find more commonly these days but just an eccentric kind of guy who enjoyed shooting and living in the country. He built this house himself in fact.

“Anyway, I didn’t know him very well when he was alive and didn’t even live close by or visit him often at all. I was down on the coast when it all started and was just finishing my degree and about to start my dissertation. So, I was in a privileged position in that I could retreat back home and stay with my family and I abided by the rules and everything. I think the first time I was critical of what was going on, the first time I became discontented, was when I was told that my degree classification could not be adversely affected by any grades I received after the pandemic. And I became uninterested in my work as it no longer mattered; I had already achieved the grade I wanted and did not have to fight to keep that mark. I would still receive my degree, I still had to pay for it, but it no longer challenged me or taught me anything. I was lucky as I hadn’t lost any family members to the disease, I hadn’t caught it, hardly anyone I even knew had caught it let alone got ill. My research, yes, was adversely affected by the closure of libraries but I had extra time and they’d already taken this into account in the mark schemes. The experience could have been a challenge and I could have learnt something from it, from adapting to new circumstances. But, no, my education was a transaction; part of the service I had bought could not be fulfilled, all that was expected of me then was mediocrity. Both us students and lecturers were opposed to the commercialisation of universities, but, in demanding things like this, we were giving in to this invisible attractive force ourselves. Giving in to the idea of education as a product.

“I think that was the first time I became aware of certain latent, unconscious processes going on in my mind looking for something more and not accepting the hegemonic individualism. More than that, the paradoxical narrative that we all needed to stay inside and look after our own needs but that this somehow constituted a monumental struggle and sacrifice for the common good that we should be given allowances for in return. Yes, if you lived in a tiny, cramped flat. But not for the privileged and the comparatively privileged like me. I carried on as I was for a while though, thinking that the virus would pass and perhaps then would be the opportunity to challenge the system. Looking back now, I think if that had happened, I would have just gone back to my old life dominated by my own thoughts and wishes. The belief that I would have acted only in the future was just another delaying tactic, another salve for my insecure conscience.

“But, obviously, that didn’t happen and the virus proliferated even further and mutated. I got my vaccine, eventually, but then that was another thing that was just sold to the highest bidder, those countries who could afford to order more than they needed did to just in case they couldn’t get enough. And everything stayed closed, and we became more atomised not just in our homes but in the world. Those outside who were at the virus’s mercy either died in droughts and floods or risked their lives in terrible wars for the right to be given a chance to live. And then here, resources got scarcer, information got scarcer, and inner cities got more densely populated as people aged and the young formed a new servant underclass. I started looking for and reading more radical ideas around what was wrong with our society and how the flagrant, individualistic pursuit of personal happiness and mere subservience to the Law and moral code of the time was exploiting others and abnegating our responsibility for opposition and altruism. A lot of people, I think, look for some great event in their lives which will make them unique, make them different and stand out. Some great trauma that would allow them to suffer afterwards and become a great artist. But, I think now, I want an event or experience that will tell me what is going on and why. I want to help and now, at last, I have an action I can take part in and I know what I need to do. But I still can’t see what the reason for my action should be. If this life is all there is, then the pursuit of happiness is justified. But it can’t be if it propagates structural violence and misery for others. I want to believe in a God or a philosophy which provides an antidote to this, but I don’t feel it in my heart. All I can perceive is a one-sided conversation in my mind. I reach out but the only reply I get is a deafening silence, consuming everything like a black whole. I can momentarily shake myself out and be passionate and fired up about things but then the fire dies down again and is extinguished by fear. I can put my belief in something” – I didn’t name it here but I was thinking explicitly of the heist – “but I am merely putting my trust in someone else’s plan or belief. I need – and I think we all need – something which motivates and justifies our actions other than our desire for a way out of this existence. This life of slowly deteriorating mediocrity until we die and cease to exist forever after.”

I wasn’t looking at Mary and Husayn any longer by this point and couldn’t bear to. I had tried to sound sincere and I believed that I was sincere. Somehow, however, I couldn’t dispel the notion that I sounded unconvincing, decadent and had not addressed what Mary wanted me to. I was right: “That’s all very well and good, but you’re just focusing on yourself again. Giving into that individualism. You’re prepared to fight for other people to a point but then you want some other reason other than just altruism to legitimate it. You want to know what’s in it for you! If you don’t get to heaven because of it, then what’s the point? That’s it isn’t? You are one of those fucking ‘anchorites’ you were talking about! You’ve come out here to masturbate your own conscience and ridiculous ideas!

“Do you know what Husayn and I have come from? Where we’ve come from?” She looked down at her axe and, with intention, placed it firmly on the ground, rising up to stand straight and tall. “London’s pretty much a battlefield with us stuck in the middle. The “Undocumented” on side – the immigrants, the unvaccinated – the “unhomed” on another – more immigrants and people fleeing the floods and droughts – and the police and the army trying to get us all. And us just trying to keep our heads down and help out where we can, sheltering people for a few nights and passing round as much information as we can lay our hands on. But there’s people who do more than that though; people fighting running battles in the streets, people ranting about the Lamb of God and the end of our world so devoid of change, hope or anything bloody new! There’s people dying in the streets and we’re just told to look away and after a while we don’t even notice it anymore! And you’re just out here listening to the birds! We don’t have time to stop and ruminate on what we ourselves want anymore or “what does this all mean?”; I’m just trying to help people, help my friends and family, make sure we can survive. That’s what we’ve been reduced to. Just literally buying into the system, focusing on what we can purchase to keep ourselves going and ignoring the rest of it. Obviously, we know it’s all wrong but it gets to you sometimes. It gets inside you, your hunger gets to you, your need to be warm gets to you and you start not noticing what’s going on around outside. Maybe we had a great opportunity when this all started but we missed it and its gone. We could’ve stopped climate change, but the opportunity’s gone. And now you can only think about surviving on after the hope has gone.” At that point her voice had already slowed and calmed from a loud rant into stilted, disjointed phrases. Pausing thoughtfully now, her speech had clearly led her to a novel appreciation of how she had lived before coming here and what had really happened. Remembering her original line of argument, she continued: “Exactly, and then we get told my somebody we don’t know on the street we need to get down here. To meet you and get some books! What the fuck is that? But at least it was something, an event, an opportunity a way out. Or that’s what I thought.”

I didn’t wait to see if she had paused only momentarily and was about to continue, “You think I know why we’re doing this? I know even less than you do. I just want a way out as well. Just because I’ve got time to think about things that only makes my life more suffocating!” Our minds and eyes distracted with each other, we hadn’t noticed the clouds thickening and the rain suddenly came down thick and heavy. Rushing inside, I went on: “Look, I know I’ve been lucky and privileged having this place out here and I know I’ve been lucky right from the start; not being stuck in the city. And, yes, there are things I didn’t know, didn’t have to know, about living in the city. But, look, I’m stuck out here in a shack surrounded by forest! You think I’m not atomised and alone like you? You think I don’t spend every day, all day, thinking about food and fuel and the rain and holes in the roof? You think I don’t regret every day the missed opportunities? You don’t think it gets to me that sometimes I feel as if I can’t breathe under burden of the only one thing actually knowable about our time and our existence: that the only way out of here, the only way anything can change for me – for any of us – will be through death. The only thing that could possibly happen that would be new. A new experience, at least for me, and a release from this historical vacuum in which we live. And trying to turn that into a cause for hope without succumbing to the bullshit from the Church?”

- 17TH FEBRUARY 2021

Recording No. UB-16.O578

Identity of Subject: Unknown

Recorded by: Unknown

Date of Recording: Unknown

Place of Interview: British Isles

Length of Interview: 00:48:01

NB: ALL PARAGRAPH AND CHAPTER BREAKS HAVE BEEN ADDED FOR THE PURPOSES OF CLARITY. REPETITIONS, HESITATIONS AND UNCLEAR SECTIONS HAVE BEEN OMMITTED.

Transcription:

I could feel the shadow of death gaining ground in my life again. Once, more than a decade ago now, I had sloughed-off the serpentine superstitious fear of a vengeful duality of God and Devil. But now, right now, I could sense the black shadow sulking at the doorway again. That suffocating weight one feels upon the chest at night, that sudden blackening beyond the eyelids one may perceive while lying in the bath. And then think of nothing but death. The mind may wander onto other trivial streams of thought, but this new awareness is crushing and irrevocable. The mundane thoughts always lead back to the fact that time is running out and the days of youth and enjoyment are fast diminishing, perhaps already gone. In fear, you pull the bedclothes over your head or open your eyes in the bath despite the stinging soap.

My name is Ebenezer and, in lieu of a written record, this is my attempt at describing the last diminishing days of my youth. I don’t have much time left, I think, but I feel I must leave a record of what is happening. It’s many years since the virus first spread and, with few people with which to share them, my memories of that time are hazy. We were told not to go outside and that the vaccine would be our saviour and that it was all going well. That is until the governments in the West hoarded doses and whole swathes of the world went without immunisation. New strains sprang up like wildfires, new viruses even too some said. The movement of people, put on hold by quarantines, started again but illegally and dangerously this time as the government tried to keep out those who had gone unvaccinated. In the wars that followed, many died and world trade and travel forced to a cataclysmic halt. We here in Britain were given jabs and we are told there are still stocks left but, as new generations are born, they are running out and the resources to restock them are unavailable. Therefore, we are told that other people must still be kept out in case a new wave enters.

I was not involved for a long time; I kept my head down, kept quiet indoors, and received my vaccination when offered. But there was growing opposition to what was going on here and in our foreign policy. It started, of course, with those who denied the virus and the vaccine but other groups soon joined. They were appalled by the treatment of the deniers and of people trying to reach Britain and our government’s stockpile of supplies. Most mainstream political groups and the Church of England were co-opted to the government’s cause. As the divide became more rigidly enforced and spoken about, the different opposition groups, gradually, coalesced. There were countless more stubborn schismatics and sectaries, of course, but most of those who opposed what was happening slowly made common cause. Included in our number are many radical Christians, Muslims, Buddhists, Jews, libertarians, Marxists and many I know who guard jealously tracts from Bunyan and obscure prophets like Joanna Southcott; many were locked up or “quarantined”. The beginnings of our movement in virus-denial was used to legitimate the imprisonment of our members under the pretext that we had refused to be given the vaccine and, therefore, posed a threat to the “herd”. They labelled us “Unbelievers” to present us as irrational and dangerous.

But many of us had been immunised and had never doubted the reality of the virus. We sought instead to rebel against the inhumane treatment of others and the monopoly on information; libraries had been locked-down in the first wave and never reopened. The lack of resources from elsewhere soon meant that technology couldn’t be repaired and access to computers and the internet dwindled to non-existence. There were still unorthodox sources of information out there, however, and many “Unbelievers” sought them out. As I said, they clung to the works of past radicals, many long past and others more contemporary to the pandemic I believe. The government would confiscate these works when they could but there were too many quietly being passed around, even by word-of-mouth. Many called us “bismillahis” by the greeting we had adopted from the Muslims among us and used to sanctify our struggle; we called our oppressors “the Beast” or “They of two-horns”, they who had built a wall not to protect us from a dangerous horde, as we were told, but to exclude the very people who needed our help and empathy.

The orthodox sources of information which fed us these lies weren’t actually official propaganda; the government farmed the contracts out to independent businesses and conglomerates all too eager to subscribe to the narrative and reap the predictable profit. But whoever they were, it made no difference; they still sang the same tune. Every new song or book recited on public radio was the same as the last. They taught us to enjoy the comforting predictability of it all. We shouldn’t worry about tomorrow and what was going on elsewhere; our society had protected us and we should just enjoy the balms of today. For others, the Church was there to teach them to bear the injustices and draconian laws so they would have a perfect moral record-book for Judgement.

They also used fear of death on those not so easily placated by monotonous salves. Where before death had, momentarily, seemed about to catch any one of us indiscriminately, we were now, apparently, safe. If we towed the line. Don’t help those in need elsewhere, as that will put you at risk of death. Enjoy the life you have been given, that we have saved for you. And if you do not and will not, look forward instead to a better life in paradise. There, your mystical obedience to the cruelties of Caesar and his Law will benefit you.

Of course, we were also fearful of death but we realised that the fight against injustice could not wait and neither could those in need of our help. I had not been fearful for a long time, though, and had, at one time, been content to obey and conform in my own lonely way. But my quiet contemplation was hindered by the limited access to books and, simultaneously, I became fascinated with others’ faith I had read about. That faith which transcended the fear of death that had dogged me as a child. The faith that was focused around justice and justification by faith; belief was enough alone to save you whereas the Law strangled you, corrupted you, and crushed others into the ground. The Church had sided with this serpent curse and betrayed its duty towards the downtrodden. Slowly, I found my way. I came in contact with others who refused to sell-out to the conglomerates and the Law.

I would date the start of this particular story of mine to the middle of last winter. Maybe more context should be given of the national events leading up to this point in time, but it’s as good a time as any to begin. Last winter was an especially mild, wet and windy one and, though the daffodils had appeared early in January, they had crumpled and rotted under the lashing rain almost as soon as they had opened. For a few years, I had been living high up on a hill on the outskirts of an abandoned Dartmoor village. The villagers had slowly aged and died and the few remaining young absconded to the cities. I myself had moved in after a distant relative had died and his nearer relations deserted to Bristol or London. The house was surrounded by dense forest providing shelter from the worst of the rains but failing to stop the damp and cold from creeping insidiously through the stone walls every night. Mains utilities had been cut off from the ghost villages for over five years now, I think, and though I did have a generator, this I used sparingly. Each day was a battle against the cold and lack of water with fires lit and rainwater boiled. Only each night, the battle would be lost again and the brief respite ended.

I lived only a day’s walk from Dartmoor gaol and, in those days, that place served as my access to the conduit of information through which I could contact other Unbelievers. The prison was now hopelessly overcrowded with criminals and political detainees and the company tasked with running it forced to co-operate with those interned in order to stay alive. I had several confrères at Princetown who, in turn, would communicate with prisoners in Exeter via guards, family and postal workers. From there, I have no idea where this chain ended up but, one day, I received word that two others would travel to the village to see me. Apparently, these two had reached out and the Princetown prisoners had agreed that my location was perfectly situated for whatever was being planned.

I was given a day when upon which they would arrive and I should journey out to meet them. You see, a specific time could not be expected as the visitors would not be able to purchase a timed ticket. At that time, all the remaining cars were used by the gerontocrats and the elderly visiting the last surviving Cornish seaside towns. Instead, people like us would literally have to jump on and off several different trains to evade police. The whole Westcountry was pretty deserted by this time so there would be few officials to impede them but, nonetheless, difficulties could arise and they could arrive at any time that day. In that particular instance, however, they arrived after I had been waiting for only just over an hour, I think. I cannot be completely sure as the cloud had been obstinately obscuring the sun’s movements for weeks now. The rain had eased somewhat, however, to what they call a “peasant drenching” in Sicily. Or at least what they once called a “peasant drenching”. Bracing for a long wait, however, my scrawny body was thick with woollens and cagouled on top.

They arrived and I swiftly approached to greet them: “Bismillah.”

“Bismillah ir-rahman ir-raheem. I’m Mary and this is Husayn”. This apparently female figure pointed across at her companion. He was similarly of indeterminate gender in his wrappings.

We set off at once. We had only about half an hour’s walk back to the house but they began recounting their tale immediately. You see, it would be no safer to talk at the house than outside as both were quite deserted. In fact, outside in the open air, the words spoken would be lost quicker, easily carried off in the wind and dissipating and merging with the susurrus of the gorse and hawthorn. As we trudged up the hill and our trousers became heavy and sodden with mud and rainwater, they told me how there was soon to be a movement of books and records between Exeter Library and Archive. One of the couriers involved was an Unbeliever, in fact, “An original sceptic”, Mary told me with blatant scorn. This meant that he was either one of those who denied the existence of the virus or one who doubted the efficacy of the vaccine. Or, most probably, both. How he had managed to keep a government job was anybody’s guess.

Anyway, through this courier I was told that we could secure the use of a library van to load the books and documents onto once we had intercepted its route to the archive. From there, they had been informed by intermediaries that, with the use of a van, my house was not that far from Exeter and would be an ideal hideout. More than that, they asked whether it was true that there was a disused tin mineshaft in the vicinity of where I lived. I replied in the affirmative. This was, evidently, where they hoped to store the documents once pilfered.

So that was the bare bones of the plot and they’d laid it all out by the time we reached the house. I had ensured, in expectation of their arrival, that I had enough logs and water laid up for three people for a few days and had worked for as many days preparing supplies. I had also shot a deer and used this for a casserole now bubbling away on the stove. We set down to dinner immediately after shedding our raincoats, ate heartily and didn’t say a word for about an hour.

You may wonder why we were planning this quite mundane heist and why we were so readily going to risk life and limb to pull it off. Because that’s what we were doing, risking our lives and none of us had any illusions about it. As soon as each of us was aware of the plan, we realised the risks involved and did not have to warn each other. And neither did we ever talk about what we could lose. We talked of the plot itself only rarely, preferring either solitary contemplation of our fears or everyday chatter as a distraction. But, as the day approached, fifteen days from when the visitors arrived, our inner lives became increasingly inflamed by the excitement and expectation of what was to come.

On that first day, after we had eaten, I quickly got up and put an old record of mine on the turntable. Frank Sinatra, Greatest Hits. It was old and scratched and tired now through excessive use but ol’ blue eyes’ golden and soothing voice still swam effortlessly through the crashing, crackling waves. Love of old music was something almost all of our number shared and though this collection didn’t represent his best work, the songs were some of his most recognisable. And we also loved music that told stories and, especially, stories of old; stories of golden, swinging London or New York before the virus, before our lives even, before anything that would connect them to our present pitiful condition. The other reason, of course, we played music constantly, almost religiously, was to mask our conversations. As isolated and bleak as this setting for our plotting was, there was still an outside chance someone may be listening or that the walls were bugged. As compliant to the prisoners’ wishes as they were, the guards, at least nominally, worked as contractors of the government. Surely, they must have had some reason to leave the city and come to this dog-end of civilisation?

So we listened and past memories of pre-pandemic evenings with friends came back as they always did. But having company now brought fresh perspectives on things and led each of our recollections to new avenues.

Just as I was remembering after-parties spent back at my house drinking glasses of wine and listening to these same songs, the next track started with me unaware and lost in the days of my youth. Mary noticed the new song at that moment, however, and proffered: “You know, the first time I had really paid attention to this song was when I heard it used as a leitmotif in a film I went to see at the cinema. I can’t remember the film but it was quite dark and this song was like a sarcastic counterpoint; very strange!”

Suddenly, I remembered seeing that film as well: “Yes! I know the film; I saw it at the cinema too! It had never been one of my favourite of Sinatra’s and I think I’d always skipped over it before, but it sent a shiver down my spine in that!”. I laughed I think, and not in the mocking tone I would use at some private joke, but in a mood of genuine good humour in the company of others desirous of the same.

As the needle wound its, probably destructive, way round the LP, so too did the songs course new and forgotten grooves in our minds. Clutching his mug in one hand and involuntarily biting the nails of the other, Husayn related, “Sinatra just reminds me of my grandfather really. I was never really much into old stuff but, every time we went round to my grandparents’ house, he would play all the old CDs: Sinatra, of course; Dean Martin; Nat King Cole; Jim Reeves… I thought they were boring but I love them now. I guess I’ve got more time to meditate on their voices and enjoy them. Always reminds me of him too…”

He was clearly quite moved remembering his grandfather so I struck in that I had similar memories: a grandfather long gone now who would play Sinatra and Bing Crosby late into the evening on warm French nights. These were memories I hadn’t thought about for a long time and I remarked, “Isn’t it strange how, with all this time spent alone apparently contemplating and thinking about the past, we forget things so easily? All alone certain things just don’t occur to you but then, as soon as you exchange a few words with another person, you start telling them about all the memories you’d thought you’d lost and they all come flooding back?”. They agreed with a happy, slightly misty-eyed laugh. Outside, I noticed that the rain had stopped and I could hear the faint but exuberant call of one blackbird to another. Observing the celandines beside the garden wall, I thought how this was the first time in a long while the flowers’ daytime opening was justified by a warm, life-giving ray of sunshine.

A few quiet moments passed and my mind returned to what we had spoken of earlier. I knew that, like me, their minds must be in constant need of new information and new books to read and explore to find some sort of eternal, timeless sense out of all that was happening. But I wondered what was so special about the documents that were being moved on that particular day in a couple weeks’ time. Seemingly reading my mind, or, perhaps, deciphering the cause for the perplexed look on my face, Mary asked, “I suppose you’re wondering what the point of us coming all the way down here is? Why are we bothering to steal this junk over all the books kept in every bloody town library in the country?”

“Well, yes, really. I mean, I’ve been in Exeter Library and I’ve been in the National Archives and British Library and know there’s not much at Exeter comparable to what’s held in London. What use to us are a few thousand tithe maps or the diaries of a couple hundred dead toffs?” Obviously, I knew there must be something else there we were looking for and was playing Devil’s advocate to get it out of these two.

“Ha, indeed. But it’s not what they’ve got there at the moment but what they’re bringing in.” She told me this as if it was the news of the century, her eagle eyes wide as if with prophecies. “Our guy tells us that they’ve got this big cache of government files dating to the time of the original pandemic and they’re going to move them into storage at the archive. We don’t know exactly what’s in them, but just having more information would shift the power to us quite considerably. We might be able to work out how much of the vaccine they’ve really got and why they didn’t bring travel restrictions in sooner so they could have been shorter and not led to this immigration ban and all these wars. And, also, what really went on in other parts of the world at that time and why they are holding back not just sensitive information but pretty much everything. We should at least be able to disprove the virus-deniers once and for all and get them more fully on side.”

In terms of the amount of information actually relayed, this answer was quite unsatisfactory and I suspected that they knew more that I wasn’t being told. Or, perhaps, they didn’t know anymore either. However, I didn’t press Mary further on the subject as her answer had been just what I had been hoping for. I felt quite elated in fact at this chance to just believe that something I could do was right and would do good without knowing all the details about it. To put my faith in a higher cause that I did not understand but which required the belief and work of countless others like me to succeed. I remembered times long before in my youth when I had grappled with my simultaneous desire for meaning and goals in life contrasted with my inability to subscribe to any one political or religious dogma. I recalled long-lost arguments from my university days between fellow students where I had remained an inconsistent bystander. Or times when, secure and closeted by a safe middle-class existence, I had no need to overcome my cognitive dissonance and put my faith in one particular religion or ideal. Now my entire consciousness was singing with the realisation that I did not, and should not, understand what I was putting my faith in; instead, I was ready to subordinate my will to this group effort which required my assistance.