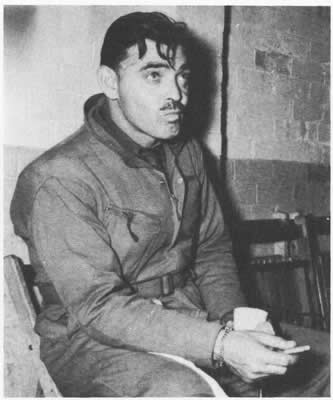

Clark Gable in the eighth Air Force

Credit: Air Power History; Washington; Spring 1999; Steven Agoratus

One day Gable "by chance" met an Army Air Force officer, Col. Luke

Smith, who-in line with Arnold's "specific" task-told him,

"Everyone wants to be a pilot, but you'd be doing a real service as a

gunner. It would help to glorify the plane crews and the grease monkeys."

Although aerial gunners were enlisted, and Gable had spoken of OCS, Smith's

proposal appealed to his occasional desire to lose himself, and perhaps his

grief, in enlisted anonymity.

MGM tempted Gable with an aviation actionadventure movie script, but, after

some thought, he turned it down, crisply telling MGM, "That's it. No more

films," and prepared to enlist. MGM blithely turned from retaining Gable to

supporting him. Its deft hand eased Gable's life in the months ahead, and helped

the AAF leverage his ability to inspire people. Taking customary charge, MGM,

with the military's assent, cloaked his pre-induction intelligence test and

physical in secrecy, although he easily passed both. The studio then arranged

for Gable's friend, tall, well-built cinematographer Andrew McIntyre, to

accompany him through OCS, possibly to help fend off fans. Demonstrating how to

build an image, MGM disingenously told the press that Gable was giving up his

Hollywood salary for enlisted pay of $66 a month. This was true, except for the

secret $150,000 MGM contract that replaced the one he gave up. Learning quickly,

the AAF revealed that McIntyre and Gable "hoped" to stay together.

Skilled himself at "smoke and mirrors," Gable told reporters that he

had asked about enlistment. Melancholy still gripped him, and he exclaimed to a

friend, "I'm going in and I don't expect to come back, and I don't really

give a hoot whether I do or not.''

For its own part, the Eighth Air Force flew its first mission on July 4, with

15th Bomb Squadron crews flying with the Royal Air Force (RAF) against airfields

in German-occupied Holland. Three aircraft, two with Eighth crews, were lost.

On August 12, the army roped off half a floor in the Los Angeles Federal

Building, and swore in Gable and McIntyre. Finally realizing Lombard's wish,

Gable told the press, "I have made application to be a gunner and I'm going

to do my very best. There's nothing else to say." MGM's well-oiled

publicity machine had plenty to say, detailing even Gable's serial number,

19125741, for fans to memorize. Hoping perhaps that readers would follow his

example, or just to stem an inevitable tide of fans, press releases noted that

Gable had made "his last public appearance for some time," and

"put aside Hollywood activities" to go in as a "buck

private."

Despite Gable's remark, clearly he could not follow up on Smith's vision, or

his own quoted desire "to be a machine gunner on an airplane and be sent

where the going is tough." Nor would he agree to appearances, despite a

hopeful AAF June 19 press release. Only Arnold knew the nature of his

assignment.

August 17, 1942, was an auspicious day, both for the AAF and for Clark Gable.

The daylight strategic bombardment offensive opened with the first Eighth Bomber

Command heavy bomber raid on the Rouen marshaling yards, flown by 97th Bomb

Group B-17s. Gable arrived at the Miami Air Officers' Training School, after an

eventful train trip from Hollywood, delayed by a "circus-like" mob of

screaming fans in New Orleans.

Gable agreeably allowed reporters to follow him, as the military hoped to use

his ability to influence people. He did not disappoint, asserting a no-nonsense

creed the army wanted recruits to hear: "I suppose after the war I will go

back to Hollywood and pictures. But right now I have plenty to do and think

about. And you can't do two things at once."After a crew cut, a supply

sergeant handed Gable a pair of oversized pants. As the normally carefully

tailored Gable puzzled over them, the sergeant noted, "They'll shrink a

little bit-and so will you." Told he must remove his famous mustache, Gable

quipped, "Suits me, I'll probably be a lot cooler anyway."

Assigned quarters in the Collins Park Hotel, now taken over, along with much

of Miami Beach, by the AAF, Gable and McIntyre changed into the ill-fitting

clothes. Shortly they were set to washing the lobby floor. Photos appeared

nationwide of the King of Hollywood scrubbing away happily just like any other

soldier.

Before the war, the AAF, spurred on by Arnold, had created an organization of

a size and quality sufficient to train civilian-soldiers quickly and efficiently

for the complexities and stresses of modern war. Taking advantage of the good

weather of the Gulf of Mexico area, bases rose from the wilderness in Florida

and nearby states. After some debate, it was decided that most recruits would go

through OCS and its West Point method of physical, emotional, and mental testing

to train them for the stress of combat.

Routinely promoted to corporal upon entry into OCS, Gable and McIntyre were

assigned to Class 42-E, of 2,600 men, and Squadron I, spiritedly dubbed

"The Iron Men of I." Gable gladly faded into anonymity, making

hospital corners on his bed, running obstacle courses, marching, and enduring

inspections. Despite his desire to get away from Hollywood, Gable's craft

benefited him in training camp. He memorized difficult class work just as he did

movie scripts, ranking 700 out of 2,600; and toughed his way through

eighteenhour day, seven day weeks in the hot Miami sun, just as he had MGM's

fourteen-hour day, six-day weeks. Even so, the forty-one-year old Gable soon

lagged on marches, an agony he deftly fine-tuned to the press as "enjoying

Army life, had lost ten pounds, and was feeling fine." Much later, he told

friends he thought they were trying to wash him out, due to his age. The Eighth

learned toughness as well, losing two bombers to fighters on September 6.

Although Gable strove to be "just a regular guy," few people at

first took him seriously; either they thought he "was involved as an actor

only," or made him the object of fun. Gable countered the jibes with gags

of his own. One morning, shaving with fifty other men, he waved around his

dentures, joking, "Look at the King, the King of Hollywood. Sure looks like

the Jack now, doesn't he?" He genuinely wanted to relate to his peers, and

soon most men regarded him as a "regular fellow." A friend said,

"I think those of us who knew Clark Gable as a soldier saw the real man

more than anyone else perhaps in his whole lifetime. He was not a movie star to

us." The fans disagreed.

Miami Beach was unenclosed, permitting delighted fans to try to get into his

quarters; watch him march; and follow, giggling, behind a fence on the beach,

while he stoically walked guard duty on the other side, dodging wads of paper

with telephone numbers. The AAF soon was forced to move his training from public

view.

Go to Page 3

[ Page 1 -

Page 2 -

Page 3 -

Page 4 -

Page 5 -

Page 6 ]

|