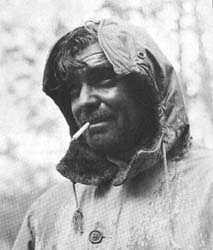

The Star -- Clark Gable Credit: The Stars by Richard Schicke

When Clark Gable died, the New York Times editorialized:"Gable was as certain as the sunrise. He was consistently and stubbornly all Man." There was nothing enigmatic about him. He was, for two generations, the popular ideal of the American male, open, uncomplicated, tough yet gentle, an appreciator of the simple American pleasures--rare steak, raw whisky, racy women.

Gable was a rare screen star in that he appealed strongly and equally to both sexes. Men saw in him a good companion for a carouse, a fight, an all-night poker session. Women saw in his lopsided grin the eternal small boy who, according to mythology, resides in all men. He might be rough at times, but they knew he could be gentled and if, from time to time, they were wise enough to let him roam free they could be sure he would return, probably looking a little sheepish. His appeal was all on the surface. He did not hide his strength under a lazy exterior like Cooper and, unlike him, there was no moral fervor lurking beneath the surface. Quite the opposite: he was rather devilishly amoral. He made no statement beyond that which was immediately apprehended upon his first entrance in a film.

But for all his simple masculine appeal, there was one intriguing feature about the parts Gable played. He performed sexual function that neither Bogart nor Cooper usually attempted. Bogart's relationship with women was hostile, Cooper's remotely chivalrous, and neither was anything but superficial, almost casual, with women. They had more important things in mind. But Gable's screen character was built upon his ability to cut across class lines to accomplish the sexual awakening of frigid, upper-class women.

His first important role, in A Free Soul (1930), cast him as a gangster who humbled proud Norma Shearer with, among other things, a sharp right to the jaw. He accomplished much the same thing in Red Dust (1932) for Mary Aster, though he gave her up for tough, good-guyish Jean Harlow. Some twenty year later, in a remake of Red Dust called Mogambo, he proved the agelessness of his appeal, by knocking the same kind of sexual sense into proud, chilly Grace Kelly. And, of course, he contributed the definitive portrait of the irresistible nature of low lustiness as Rhett Butler in GWTW.

Interestingly, in his own marriages he was torn between the chilly sophisticates and the down-to-earth types. Life being unlike a screen play, he found happiness only with the latter type --- Carole Lombard and Kay Williams.

It's easy enough to understand why Gable was elected "King" of Hollywood in a poll of editors conducted by Ed Sullivan in 1938. Though his films carried far less social commentary than those of Cooper and Bogart, he was very much an expression of a nation's feelings during the Depression Decade. Gable elicited an immediate and direct response from his audiences, though he played almost exclusively in highly irrelevant films---lightweight comedies and adventures, both historically and contemporary, that had little to do with the great questions of the day.

He was a roguish, down-to-earth, adventurous man, and a major part of his appeal was his lack of roots. Gable was at home everywhere--in oil fields, in city streets and penthouses, astride a horse, in sundry jungles, in any historical era. Everywhere he was the democratic man, both in his contempt for the alleged thinness of aristocratic blood and in his envious attraction to the good, soft life of the upper classes. He nearly always played a self-made man and the role carried with it a built-in contempt for the man who inherited his wealth or was not driven by the same lust for life that motivated him.

As for women, it was always a toss-up whether, having forced a high=born heroine to admit the earthy urgency of her desires, he would be satisfied or having accomplished this task, would abandon her for the common woman who understood all this in her bones and could please him without need of her night-school courses in the art of love.

How appealing all this was! The men, of course, saw in Gable a man capable of living a life of adventure and easy conquest just like the one they themselves conducted in their fantasies. The women could lead multiple fantasy lives in his pictures. They could imagine, themselves as the aristocratic ladies first fighting off, then yielding to, his rough advances. But once the picture ended, they could console themselves with the knowledge that he was also attracted to ordinary women.

As for Gable himself, his early life was as restless as that of one of his screen characters. His father was a roving oil field boomer who for the most part left his son to his own devices. His mother died not long after giving him birth. Periods of prosperity and tranquillity alternated with periods of troubled restlessness. A stepmother gentled him and gave him what maternal love he experienced.

When he was fifteen he left his Ohio farm home to work in Akron. There he worked backstage with a stock company during his free time. He left to join his father in the oil fields after his stepmother died, then left that miserable existence for another city and another theatrical troupe. It ran out of funds in Butte, Montana, and he drifted to lumber camps and then to Portland, where he met Josephine Dillion, director of a local stock company. Eventually they married, briefly and unhappily. Together they went to Hollywood, where she worked as a drama coach and he got some movie bits. Stock assignments in Los Angeles and Houston, work in New York, then the lead in the Los Angeles production of the Last Miles---the part which had made Spencer Tracy a star in New York---led him back to the movies.

Now a more polished performer, he had the usual troubles securing work ("his ears are too big," cried Jack Warner upon seeing a test) but did well enough for MGM to take a chance on him opposite Shearer in A Free Soul; the theory was that he would be too innocuous either to upset or to upstage Irving Thalberg's wife. Things did not quite work out that way. Four years late Gable was in the box-office top ten, was earning $3,500 a week and had won an Academy Award for It happened one night. "You know," he said shortly before he died, "this King stuff is pure bullshit. I eat and sleep and go to bathroom just like everyone else. There's no special light that shines inside me and makes a star. I'm just a lucky slob from Ohio. I happened to be in the right place at the right time and I had a lot of smart guys helping me---that's all." There is more truth than modesty to his statement. But he did leave, on screen, the special arrogance of a man who was comfortably sure of his identity and of his untrammeled masculinity.

|