Intro

IntroThroughout the years his personal life has been the source of much theater and poetry, both as villain and mad genius. His musical art has similarly been criticized by many. In the late 18th century, Dr. Charles Burney characterized Gesualdo's modulation, as "forced, affected, and disgusting." Igor Stravinsky, in the last century, lauded Gesualdo's work as profoundly visionary, and commissioned a statue of Gesualdo. One recent critic described Gesualdos music as sounding like, "Wagner gone wrong." However, Gesualdo died almost exactly 200 years before Richard Wagner was born.

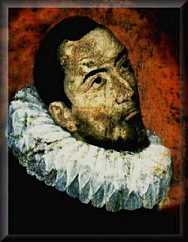

Who was this man who could break all the rules in such a flamboyant manner and excite so much controversy in his own eccentric age and continues to excite debate 400 years later?

Don Carlo was born around 1560 (possibly March 8, 1557) to Don Fabrizio Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, and Princess Geronima Borromeo, sister of Saint Carlos Borromeo.

Carlo was the second son and consequently, was not heir to the family estates and title. Free of dynastic responsibilities, he used his leisure time to study music. He is said to have been taught by Pomponio Nenna, but this is unlikely as the later was born in 1560.

He maintained a private musical camerata consisting of some of the foremost musicians in Naples, including Scipione Stella (composer), Scipione Dentice (composer and harpsichordist), Rocco Rodio (musician and theoretician), and Leonardo Primavera dellArpa (another eminent composer and performer). This camerato also included leading poets such as Torquato Tasso.

This period of carefree enjoyment of art, music and poetry was to be interrupted when his elder brother, Don Luigi Luigi Gesualdo, suddenly died in an equestrian accident, making young Carlo the heir apparent in 1585.

Almost immediately, dynastic considerations were pressed on Don Carlo, and a marriage was arranged between him and his first cousin, Donna Maria d’Avalos, then said to be the most beautiful woman in the Kindom of the Two Cicilies. We are told by a contemporary writer that Don Carlo, however, cared for little but music. By the age of 21, the lovely Donna Maria had already been widowed once and divorced once.

Her first husband, Ferderico Carafa, was reported to have died suddenly, due to excessive reiteration of carnal embrace with her (troppo reiterare con quella i congiungimenti carnali). Her second marriage to Don Alfonso, son of the Marquis di Giuliano, ended with the granting of divorce by the Pope.

She was almost immediately affianced to Don Carlo Gesualdo, in 1586.

The birth of a son, Don Emmanuele Gesualdo, in 1588, freed Don Carlo of his immediate dynastic concerns, and its quite possible that he returned to his apollonian pursuits to the neglect of his very sexually experienced bride.

Unfortunately, Donna Maria was probably already in love with her first husbands brother, Don Fabrizio Carafa III, duke of Andria, reputed to be the most handsome and accomplished nobleman of the region. Like his brother, he was fated to lose his life in the embrace of Donna Maria.

Don Carlo, after four years immersed in music and hunting, was awakened to the fact that his lovely bride was having an affair under his nose, in their Naples residence, the Palazzo San Severino.

Furious, and eager to rid himself of energetic spouse, Don Carlo removed the bolts from the doors of the bedchambers and declared he was leaving Naples for a hunting expedition on October 16, 1590, and would not return for several days.

Furious, and eager to rid himself of energetic spouse, Don Carlo removed the bolts from the doors of the bedchambers and declared he was leaving Naples for a hunting expedition on October 16, 1590, and would not return for several days.

Subsequently, Donna Maria sent a message to the Duke of Andria, requesting a visit, late that night. She had her maid dress her and sent her maid to her room and effusively greeted her lover in her chamber.

The next thing her chamber maid knew was she heard the thundering of footsteps on the palazzo stairs and shouts of men and gunshots. Don Carlo was heard to yell, I cant believe she is really dead! and numerous stab wounds were applied to the bodies of the unfortunate Donna Maria and the Duke. The next morning, Donna Maria's body was found with her throat slit and the Dukes body was found, covered in blood, wearing Donna Marias nightgown.

The scene, the Palazzo San Severino, remained vacant for some time after the murders, and to this day it is said to be haunted by the ghost of Donna Maria.

It was the O.J. Simpson case of its time, only there was no doubt who the killer was

Much was made of it in song and verse, and nearly everyone took the side of the slain lovers.

The spirit of the times did not sympathize with the passions of the grim Gesualdo.

The chivalric code of courtly love disregarded the marital status of the lovers, with only two provisos: that the lady and her knight should not be married to one another, and that they be of equal social status. Therefore, it was the lady and her love who were fit for epic poetry.

Don Carlo fled Naples and returned to the mediaeval fortress in Gesualdo. He took care to have the trees cut from around his castle so as to avoid possibility of ambush. Although he was a prince, and therefore immune from criminal prosecution, he was not immune to assassination and the vendettas of the powerful d’Avalos and Carafa families. Living in isolation and anxiety, and a growing melancholy that bordered on madness, the prince turned to music with a vengeance.

In 1591, Don Carlos father died, making him Prince of Venosa, and he now had the responsibility of governing the region. Once again pressed with dynastic issues, and prodded by his uncle, Cardinal Alfonso Gesualdo, the Prince agreed to remarry. This marriage was to be more than a simple dynastic union, and more than just a romantic affair, however.

Don Carlo was betrothed to Donna Eleonora d’Este, cousin to the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso II. At this time, Ferrara was the jewel city of renaissance culture, now outshining even Florence.

At Ferrara were the foremost musicians of the day, including his hero, Luzzasco Luzzaschi and Gerolamo Frescobaldi (later organist at St. Peters, Rome). Also at Ferrara was Don Carlos old friend, the Poet Torquato Tasso, who submitted some 40 madrigal lyrics to Don Carlo, of which eight are known to have been published with settings by the Prince.

Don Carlo Arrived at Ferrara on the eve of his wedding, February 18, 1594, bringing books of his madrigals and other musical works to impress and share with the court, and especially with Luzzasco Luzzaschi, affectionately called, Zasco.

"... I met the Prince at the ferry... He has it in mind to beseech Your Highness most warmly that tomorrow evening you will permit him to see Signora Donna Eleonora.

The Prince, although at first view he does not have the presence of the personage he is, becomes little by little more agreeable and for my part I am sufficiently satisfied of his appearance.

He talks a great deal and gives no sign, except in his portrait, of being a melancholy man.

He discourses on hunting and music and declares himself an authority on both. Of hunting he did not enlarge very much since he did not find much reaction from me, but about music he spoke at such length that I have not heard so much in a while year. He makes open profession of it and shows his works in score to everybody in order to induce them to marvel at his art. he has with him two sets of music books in five parts, all his own works, but he says that he only has four people who can sing for which reason he will be forced to take the fifth part himself...

He says that he has abandoned his first style and has set himself to the imitation of Luzzaco [Luzzaschi], a man whome he greatly admires and praises, although he says that not all of Luzzasco's madrigals are equally well written, as he claims to wish to point out to Luzzasco himself.

This evening after supper he sent for a cembalo [harpsichord] for which reason, so as not to pass the evening without music, he played the lute for an hour and a half.

Here perhaps Your Highness would not be displieased if I were to give my opinion, but I would prefer, with you leave, to suspend my judgement until more refined ears have given theirs.

It is obvious that his art is infinite, but it is full of attitudes, and moves in an extraordinary way. However, everything is a matter of taste."

Letter from Count Alfonso Fontanelli to Duke of Ferrara, 2-18-1594.

Boldly criticizing Luzzaschi, Don Carlo was clearly much more eager to make music than to make love. Then, as now, the Princes musical attitudes and extraordinary modulation were controversial.