Skip down to:

Andersonville

Civil War Prison Camps

A Memorial to All U.S. Prisoners of War

More Pictures

�

�

Andersonville, or Camp Sumter as it was officially known, was one of the largest of many Confederate military prisons established during the Civil War. It was built early in 1864 after Confederate officials decided to move the large number of Federal prisoners kept in and around Richmond, Virginia, to a place of greater security and a more abundant food supply. During the 14 months the prison existed, more than 45,000 Union soldiers were confined here. Of these, almost 13,000 died from disease, poor sanitation, malnutrition, overcrowding, or exposure to the elements.

The prison pen initially covered about 16 1/2 acres of land enclosed by a 15-foot-high stockade of hewn pine logs. It was enlarged to 26 1/2 acres in June 1864. The stockade was in the shape of a parallelogram 1,620 feet long and 779 feet wide. Sentry boxes, or "pigeon-roosts" as the prisoners called them, stood at 30-yard intervals along the top of the stockade. Inside, about 19 feet from the wall, was the "deadline", which the prisoners were forbidden to cross upon threat of death. Flowing through the prison yard was a stream called Stockade Branch, which supplied water to most of the prison. Two entrances, the North Gate and the South Gate, were on the west side of the stockade. Eight small earthen forts located around the exterior of the prison were equipped with artillery to quell disturbances within the compound and to defend against feared Union cavalry attacks.

The first prisoners were brought to Andersonville in February 1864. During the next few months approximately 400 more arrived each day until, by the end of June, some 26,000 men were confined in a prison area originally intended to hold 10,000. The largest number held at any one time was more than 32,000--about the population of present-day Sumter County--in August 1864. Handicapped by deteriorating economic conditions, an inadequate transportation system, and the need to concentrate all available resources on its army, the Confederate government was unable to provide adequate housing, food, clothing, and medical care to their Federal captives. These conditions, along with a breakdown of the prisoner exchange system, resulted in much suffering and a high mortality rate. On July 9, 1864, Sgt. David Kennedy of the 9th Ohio Cavalry wrote in his diary: "Wuld that I was an artist & had the material to paint this camp & all its horors or the tongue of some eloquent Statesman and had the privleage of expresing my mind to our hon. rulers at Washington. I should gloery to decribe this hell on Earth where it takes 7 of its ocupiants to make a Shadow."

When Gen. William T. Sherman's Union forces occupied Atlanta on September 2, 1864, bringing Federal cavalry columns within easy striking distance of Andersonville, Confederate authorities moved most of the prisoners to other camps in South Carolina and coastal Georgia. From then until May 1865, Andersonville was operated on a smaller basis. When the war ended, Capt. Henry Wirz, the stockade commander, was arrested and charged with conspiring with high Confederate officials to "impair and injure the health and destroy the lives...of Federal prisoners" and "murder, in violation of the laws of war." Such a conspiracy never existed, but public anger and indignation throughout the North over the conditions at Andersonville demanded appeasement. Tried and found guilty by a military tribunal, Wirz was hanged in Washington, D.C., on November 10, 1865. A monument to Wirz, erected by the Georgia Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, stands today in the town of Andersonville.

Andersonville prison ceased to exist in May 1865. Some former prisoners remained in Federal service, but most returned to the civilian occupations they had before the war. During July and August 1865, Clara Barton, a detachment of laborers and soldiers, and a former prisoner named Dorence Atwater, came to Andersonville cemetary to identify and mark the graves of the Union dead. As a prisoner, Atwater was assigned to record the names of deceased Union soldiers for the Confederates. Fearing loss of his death record at war's end, Atwater made his own copy in hopes of notifying the relatives of some 12,000 dead interred at Andersonville. Thanks to his list and the Confederate records confiscated at the end of the war, only 460 of the Andersonville graves had to be marked "unknown U.S. soldier."

The prison site reverted to private ownership in 1875. In December 1890 it was purchased by the Georgia Department of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union veterans organization. Unable to finance improvements needed to protect the property, this group sold it for $1 to the Woman's Relief Corps, the national auxiliary of the G.A.R. The Woman's Relief Corps made many improvements to the area with the idea of creating a memorial park. Pecan trees were planted to produce nuts for sale to help maintain the site and states began erecting commemorative monuments. The W.R.C. built the Providence Spring House in 1901 to mark the site where, on August 9, 1864, a spring burst forth during a heavy summer rainstorm--an occurrence many prisoners attributed to Divine Providence. The fountain bowl in the Spring House was purchased through funds raised by former Andersonville prisoners.

In 1910 the Woman's Relief Corps donated the prison site to the people of the United States. It was administered by the War Department and its successor, the Department of the Army, until its designation as a national historic site. Since July 1, 1971, the park has been administered by the National Park Service.

In the South, captured Union soldiers were first housed in old warehouses and barns. As the number of prisoners increased, camps were built specifically as prisons in Florence, South Carolina, Millen and Andersonville, Georgia, and many other locations. Most were wooden stockades enclosing open fields, as depicted in the lithograph of the Andersonville camp by former inmate Thomas O'Dea. In the North, officials converted many Federal camps of instruction into prisons. Stockades were placed around Camp Butler in Illinois, Camp Chase in Ohio, and camps at Elmira, New York. Other Confederate prisoners were held at Fort McHenry in Baltimore and Fort Warren in Boston Harbor.

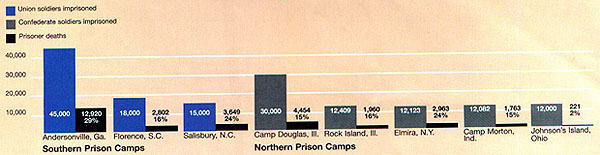

The confined soldiers suffered terribly. The most common problems confronting prisoners both North and South were overcrowding, poor sanitation, and inadequate food. Mismanagement by prison officials, as well as by the prisoners themselves, worsened matters. The end of the war saved hundreds of prisoners from an untimely death, but for many the war's end came too late. Of 194,732 Union soldiers held in Confederate prison camps, some 30,000 died while captive. Union forces held about 220,000 Confederate prisoners, nearly 26,000 of whom died. The mortality rates for some of the Civil War prison camps are shown below.

�

It is neither dishonorable nor heroic to be a prisoner of war. Often capture comes as a complete surprise and is frequently accompanied by injury. Internment is a physical and emotional ordeal that is all too often fatal.

Throughout our history, American prisoners of war have confronted varying conditions and treatment. These are affected by such factors as climate and geography, a culture's concept of the armed forces, its view of reprisals as a "legitimate" activity of war, and even something as simple as the whim of individual captors. International rules require that prisoners of war be treated humanely and not be punished for belonging to enemy forces. History has taught that the concept of what is "humane treatment" varies with different nations and cultures.

The American prisoner of war experience has been one of constant trials. Prisoners have suffered and seen fellow captives die from disease, starvation, exposure, lack of medical care, forced marches, and outright murder. They have been victims of war crimes such as torture, mutilation, beatings, and forced labor under inhumane conditions. POWs have been targets of intense interrogation and political indoctrination. At times they have faced severe privations because their captors were not adequately prepared to care for them.

Some Americans have experienced the prisoner of war ordeal for a few days, others for years. All have experienced the loss of freedom. This is the most important story told at Andersonville National Historic Site. To fully understand this loss is to cherish freedom all the more.

Handmade shirt and trousers worn by Sgt. Nathan P. Kinsley (in photograph) of Co. H, 145th Pennsylvania Infantry, while imprisoned at Andersonville 1864-65.

The Georgia Monument in Andersonville National Cemetary honors all United States prisoners of war.

Return to News page.