Implications of ‘New’ Literacies for Writing Research

Colin Lankshear and Michele Knobel

Keynote address to the Literacies and Writing SIG

AERA 2003, Chicago, April 21.

Introduction

This paper presents a simple way of looking at research in terms of its ‘logic’ such that it is possible to identify some implications of ‘new’ literacies for research in the area of writing. We will begin by presenting a diagrammatic view of the logic of research and then move on to a preliminary account of how we think of ‘new’ in relation to new literacies. On the basis of this conception of ‘the new’ we will then briefly outline some of the practices we identify as ‘new’ literacies in our book, New Literacies: Changing Knowledge and Classroom Learning (Lankshear and Knobel 2003). Finally, we will draw on examples of these new literacies to suggest some of the kinds of things they may imply for developing approaches to and programs for writing research.

The ‘logic’ of research

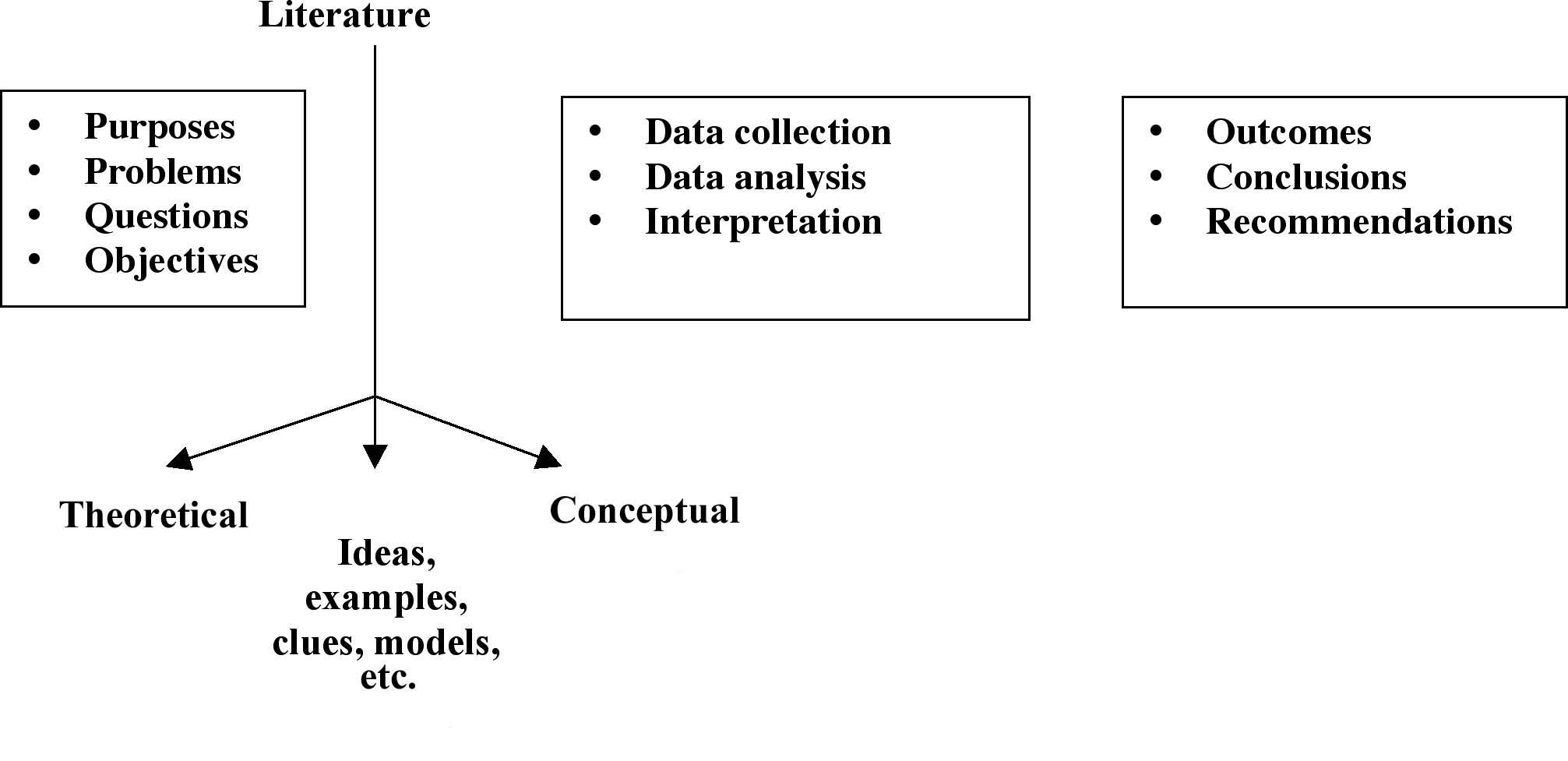

We think of the logic of research in terms of the relationships between four main ‘constitutive components of research as a process.

Figure 1: A research ‘logic’

Looking ahead, and after outlining our ideas about new literacies, we will ask what some of their implications are for the kinds of Research Purposes (including research problems, questions, specific objectives) investigators might have in the area of writing; for the Literature to be Reviewed and for the Frameworks to be informed by and developed out of one’s engagement with literature; for Collecting and Analyzing Data and Interpreting one’s analysis; and for the kinds of Outcomes (including conclusions and recommendations) that might emerge from researching new literacies.

When is ‘new’

It has now become common for literacy scholars and researchers to use the qualifier ‘new’ in relation to ‘literacy’ and ‘literacies’. New literacy talk occurs in two main ways—linked contingently to some extent—that we refer to as paradigmatic and ontological senses respectively of “new”.

The paradigmatic sense occurs in talk of the New Literacy Studies (Gee 1996, 2000; Street 1993) to refer to the sociocultural approach to understanding and researching literacy. In this sense, the New Literacy Studies comprise a new paradigm for looking at literacy as opposed to the paradigm, based on psychology, which was already well established. The use of “new” here parallels that which is involved in names for initiatives or movements such as the New School of Social Research, the New Science, the New Criticism (and New Critics), and so on. In all such cases, the proponents think of their project as comprising a new and different paradigm relative to an existing orthodoxy or dominant approach.

What we call the ontological sense of ‘new’ refers to the idea that changes have occurred in the character and substance of forms and practices of literacy associated with changes in technology, institutions, media, the economy, and the rapid movement toward global scale in manufacture, finance, communications and so on. These changes have impacted on social practices in all the main areas of everyday life within modern societies: in work, at leisure, in the home, in education, in the community, and in the public sphere. Established social practices have been transformed, and new forms of social practice have emerged and continue to emerge at a rapid rate. Many of these new and changing social practices involve new and changing ways of producing, distributing, exchanging, and receiving texts by electronic means. These have generated new multimodal forms of texts that can arrive via digital code—what Richard Lanham (1994) calls ‘the rich signal’—as sound, text, images, video, animations, and any combination of these.

In this ontological sense, the category of ‘new literacies’ largely covers what are often referred to as ‘post typographic’ forms of textual practice: literacies mediated by use of new computing and communication technologies (CCTs). These include using and constructing hyperlinks between documents and/or images, sounds, movies, etc., semiotic languages (such as those used by the characters in the online game, Banja, or emoticons used in email, online chat space or in instant messaging), manipulating a mouse to move around within a text, reading file extensions and identifying what software will ‘read’ each file, producing ‘non-linear’ texts, navigating three-dimensional worlds online, and so on. These are literacies that involve to a greater or lesser extent some ‘new kind of stuff’ or are to a greater or lesser extent different in kind from what we had previously known: for example, they are associated with the world of ‘bits’ as distinct from the world of ‘atoms’ (and with trappings and connotations of that world, such as the hyper-acceleration of time and the compression of space into a ‘real time global’ that can in a meaningful sense be everywhere and nowhere).

To a large extent it is literacies in this post typographic sense that schools have identified as their main challenge so far as incorporating ‘new literacies” into their programs and as media for learning are concerned. Correspondingly, it is these post typographic literacies that educational researchers generally and language and literacy researchers more specifically often most immediately identify as ‘new’ literacies.

At the same time, however, new literacies associated with contemporary changes in our institutions and economy do not necessarily involve using new electronic CCTs or, if they do, this may not be their most important aspect. This is especially true of some important work-related literacies, as work by Glynda Hull and colleagues since the early 1990s makes clear (see, for example, Gee, Hull and Lankshear 1996; Hull et al. forthcoming).

Without wanting to underestimate the huge significance of post typographic, electronically-mediated literacies within everyday life, and their leading place within any useful conception of ‘new literacies’, we nonetheless want to stake a claim for including under the umbrella of ‘ “new” literacies’ a number of practices that do not necessarily involve use of CCTs. This suggests to us a third sense of ‘new’ that, for want of a better word, we might call chronological. This third sense is more vague and impressionistic than the others. It is the idea of ‘new literacies’ as ones that are relatively new in chronological terms and/or that are new to being thought about as literacies, and that are important to take into account in literacy education.

The literacies we will talk about here all presuppose the paradigmatic sense of ‘new’. (Indeed, we think that all sensible talk of ‘literacy’—since it is a soci(ologic)al concept—presupposes a sociocultural perspective, and we see the task of winning back the concept of literacy from those who have appropriated its ‘capital’ for purposes better served by psychology and psychometrics as a political task.). We will, then, assume a sociocultural perspective as given, and focus almost entirely on new literacies in the ontologicaland chronological senses.

At the same time, we recognise that our attempt to delineate ‘the new’ is tentative, preliminary, and most definitely contestable. Other people will prefer different emphases and constructions altogether. Consequently, a first implication of ‘new’ literacies for writing research is that anyone wanting to research new literacies must decide ‘when is “new”?’ and consider what might count as an adequate/robust/substantial conceptual and theoretical framework for constructing the ‘new’ and how to defend this position against other coherent possibilities.

Some typical ‘new’ literacies

(i) Scenario planning: A chronologically new literacy

Scenario planning has emerged during the past 40-50 years as a generic technique to stimulate thinking about the future in the context of strategic planning (Cowan et al. 1998). It was initially used in military planning, and was subsequently adapted for use in business environments (Wack 1985a, 1985b; Schwartz 1991; van der Heijden 1996) and, most recently, for planning political futures in such countries as post apartheid South Africa, Colombia, Japan, Canada and Cyprus (Cowan et al. 1998).

Scenarios are succinct narratives that describe possible futures and alternative paths toward the future, based on plausible hypotheses and assumptions. The idea behind scenarios is to start thinking about the future now in order to be better prepared for what comes later. Proponents of scenario planning make it very clear that scenarios are not predictions. Rather, they aim to perceive futures in the present. In Rowan and Bigum’s words (1997: 73), they are

a means for rehearsing a number of possible futures. Building scenarios is a way of asking important ‘what if’ questions: a means of helping groups of people change the way they think about a problem. In other words, they are a means of learning.

Scenario planning is very much about challenging the kinds of mind sets that underwrite certainty and assuredness, and about ‘reperceiving the world’ (ibid.: 76) and promoting more open, flexible, proactive stances toward the future. As Cowan and colleagues (1998: 8) put it, the process and activity of scenario planning is designed to facilitate conversation about what is going on and what might occur in the world around us, so that we might ‘make better decisions about what we ought to do or avoid doing’. Developing scenarios that perceive possible futures in the present can help us ‘avoid situations in which events take us by surprise’. They encourage us to question ‘conventional predictions of the future’, as well as helping us to recognize ‘signs of change’ when they occur, and establish ‘standards’ for evaluating ‘continued use of different strategies under different conditions’ (ibid.). Very importantly, they provide a means of organizing our knowledge and understanding of present contexts and future environments within which decisions we take today will have to be played out (Rowan and Bigum 1997: 76).

Within typical approaches to scenario planning a key goal is to aim for making policies and decisions now that are likely to prove sufficiently robust if played out across several possible futures. Rather than trying to predict the future, scenario planners imaginatively construct a range of possible futures. In light of these, which may be very different from one another, policies and decisions can be framed at each point in the ongoing ‘present’ that will optimise options regardless of which anticipated future is closest to the one that eventually plays out in reality.

Scenarios must narrate particular and credible worlds in the light of forces and influences currently evident and known to us, and that seem likely to steer the future in one direction or another. A popular way of doing this is to bring together participants to the present policy or decision making exercise and have them frame a focusing question or theme within the area they are concerned with. If, for instance, our concern is with designing courses in literacy education and technology for inservice teachers presently in training, we might frame the question of what learning and teaching of literacy and technology might look like within educational settings for elementary school age children 15 years hence. Once the question is framed, participants try to identify ‘driving forces’ they see as operating and as being important in terms of their question or theme. When these have been thought through participants identify those forces or influences that seem more or less ‘pre-determined’: that will play out in more or less known ways. Participants then identify less predictable influences, or uncertainties: key variables in shaping the future which could play out in quite different ways, but where we genuinely can’t be confident one way or another about how they will play out. From this latter set, one or two are selected as ‘critical uncertainties’ (Rowan and Bigum 1997: 81). These are forces or influences that seem especially important in terms of the focusing question or theme but which are genuinely ‘up for grabs’ and unpredictable. The ‘critical uncertainties’ are then ‘dimensionalized’ by plotting credible poles: between possibilities that, at one pole are ‘not too bland’ and, at the other, not too ‘off the wall’. These become raw materials for building scenarios: stories about which we can think in ways that suggest decisions and policy directions now.

(ii) Culture and News Jamming

Culture Jamming at Adbusters

At Adbusters Culture Jamming Headquarters (www.adbusters.org), a series of elegantly designed and technically polished pages present information about the organization and its purposes, describe an array of culture jamming campaigns, describe the Adbusters paper-based magazine, and target worthy media events and advertising, cultural practices, and super-bloated corporate globalisation with knife-sharp critiques in the form of parodies, exposés of corporate wheelings and dealings, and/or online information tours focussing on social issues. By turning media images in upon themselves, or by writing texts that critique the effects of transnational companies, the Adbusters ‘culture jamming’ campaigns scribe new literacy practices for all people. An early image from a critique of a past trend to claim an ‘equality’ ethic in the fashion world shows how combining familiar images and tweaking texts can produce bitingly honest social commentaries that everyone everywhere is able to read—a kind of global literacy.

The nature of culture jamming and the philosophy that underlies it, together with many practical examples of how to enact culture jamming literacies, are described in a recent book. Culture Jam: How to Reverse America’s Suicidal Consumer Binge—And Why We Must, is written by Kalle Lasn, publisher of Adbusters magazine and founder of the Adbuster Media Foundation. The potential effectiveness of culture jamming was clearly demonstrated recently. An email posting in January 2002 to the Culture Jammers Network ([email protected]) informed recipients that Adbusters’ activities had come under increased scrutiny following September 11. According to the posting,

Recently, our Corporate America Flag billboard in Times Square, New York, attracted the attention of the federal [U.S.]Department of Defense, and a visit by an agent who asked a lot of pointed questions about our motivations and intent. We wondered: What gives? “Just following up a lead from a tip line,” the agent admitted.

Adbusters were clearly worrying people in high places. They observed that any campaign daring to question ‘U.S. economic, military or foreign policy in these delicate times’, or any negative evaluation of how the US is handling its ‘War on terrorism’, runs the risk of being cast as ‘a kind of enemy of the state, if not an outright terrorist’.

Adbusters’ response was to mobilise internet space to engage in a classic act of cyberactivist literacy. The posting asked other Culture Jammers whether their activities had received similar attention, noting that they had received messages from other activist organisations that had found themselves under investigation ‘in a political climate that’s starting to take on shades of McCarthyism’. Noting that they could live with vigilance, but that intimidation amounting to persecution is “another bucket of fish”, Adbusters established it own ‘rat line’ and invited others to publicise instances of state persecution public within a medium which has immediate global reach.

If you know of social marketing campaigns or protest actions that are being suppressed, or if you come across any other story of overzealous government ‘information management’, please tell us your story. Go to http://www.adbusters.org/campaigns/flag/nyc/.

News Jamming at Peacespace: Representative spoofs from the latest U.S. war

News jamming describes oppositional tactics that work to critique mainstream broadcast media versions of the ‘news’. The aim of news jamming is to urge people to read media and other messages in ways that open onto critical—and multiple—analyses and interpretations of these messages. News jamming generally takes one of two forms: (1) hard-edged spoofs of mainstream media coverage of events or official responses to events that cut to the heart of contradictions or fabrications delivered as ‘news’, and (2) multimodal research that challenges the way in which events and/or people are represented in the commercial media.

At present, the war on Iraq has generated gigabytes of news jamming practices

online. In one memorable spoof, titled ‘State of the Union Speech’,

sound bytes from George W. Bush’s past speeches have been spliced together

to produce an alternative state of the union speech that shows Bush speaking

to a packed house. Among other things, the spliced George Bush proclaims, ‘I

told our country, and I told the world: If it feels good, do it’ (www.cfox.com/geeks/geekstuff/union.mov).

The movie shows Bush receiving a standing ovation from his audience for this

and other comments. Another spoof critiques the design and intent of the

U.S. Department of Homeland Security suggestions for preparing oneself for

terrorist

attacks (e.g., www.ready.gov/nuclear.html). The spoof website (www.idlewords.com)

takes images from the Department’s visual guides to being prepared

(e.g., www.ready.gov/nuclear_visual.html) and rewrites the commentary that

accompanies

each one (see Figure 2).

Image |

Original advice if there is a nuclear explosion |

Spoof advice |

|

Consider if you can get out of the area; | Most nuclear explosions will be less than a city block wide. Consider running in a direction away from the blast. |

|

Or if it would be better to go inside a building and follow your plan to shelter-in-place. |

|

Source: http://www.ready.gov/nuclear_visual.html, http://www.idlewords.com/nuclear_blast.htm

Figure 2: News Jamming the Department of Homeland Security

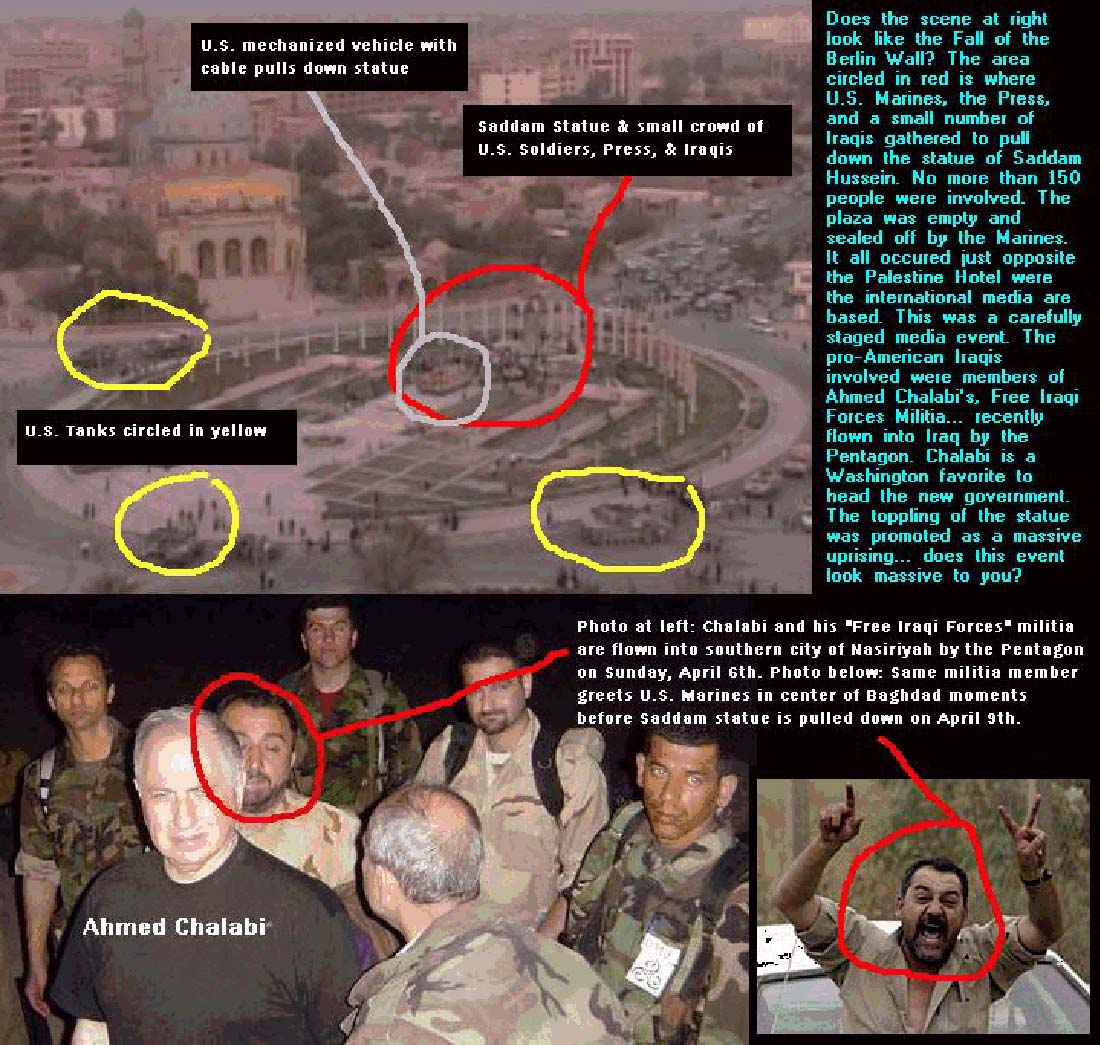

The second form of news jamming aims at detecting distortion and manipulation in news broadcasts. A recent example that has caught worldwide attention has been broadcast media coverage of the toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in el-Fardos Square, Baghdad. The event was reported on television as being cheered on by hundreds of Iraqis (see Figure 3).

Source: CNN.com (April 9, 2003; http://www.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/meast/04/09/sprj.irq.statue/)

Figure 3: CNN website image that accompanies report of the toppling of Hussein

statute in el-Fardos Square.

However, the wide-angle photographs of el-Fardos Square where the statue was located, taken from a Reuters website and posted on the NYC Indymedia Center weblog (Fozzy 2003), suggest that the scenes of celebrating Iraqi throngs were carefully staged. The photographs posted in this weblog entry show a more or less empty square ringed by U.S. tanks, and a small crowd of no more than 150 Iraqis gathered behind the statue as it is pulled down. A subsequent analysis of these pictures posted on the Information Clearing House website (www.informationclearinghouse.info/article2842.htm) pointedly draws attention to the location of the crowd in front of Hotel Palestine, where international journalists were housed at the time. This analysis also suggests that members of the crowd may have been Iraqi militia men in the employ of the U.S. military, paid to promote the overthrow of the Hussein regime—at least one member of the Free Iraqi Forces militia is identified in press photographs of Iraqis welcoming U.S. soldiers into el-Fardos Square in Baghdad (see Figure 4).

Source: Information Clearing House (April 10, 2003; http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article2842.htm)

Figure 4: Democratic opportunism

(iii) Blogging: Personal weblogs from Jane Doe to Andrew Sullivan

In a May 2002 online archive of Wired, a writer for the New York Times, Andrew Sullivan, suggested that ‘blogging’—the practice of publishing personal weblogs—is changing the media world. He goes so far as to suggest that blogging could ‘foment a revolution in the way journalism functions in our culture’ (Sullivan 2002: 1).

Weblogs are online lists of hyperlinks to websites found ‘newsworthy’ by the weblogger (or ‘blogger’ for short) and/or personal diaries or journals that are added to by the blogger anywhere from every now and then to multiple times a day. Sullivan traces the history of weblogs from the mid 1990s, when blogging was confined to small scale ‘sometimes nutty, sometimes inspired writing of online diaries’ (2002: 1). Today, however, the internet is home to blogs covering diverse topics and types. Sullivan notes examples ranging from tech blogs, sex blogs, drug blogs and onanistic teenage blogs to news and commentary blogs. The latter comprise sites that are ‘packed with links and quips and ideas and arguments’ that as recently as 2001 ‘were the near monopoly of established news outlets’ (2002: 1). While they are often still ‘nutty’, and can be painfully banal, prejudiced, angst-ridden, or downright nasty, they can also be erudite and scale the pinnacles of sophisticated commentary and critique. Weblogs transcend traditional media categories. In the broad area of journalism, for instance, they may be as ‘nuanced and well-sourced as traditional journalism’ yet have ‘the immediacy of talk radio’ (Sullivan 2002: 1).

Furthermore, blogging is in tune with the tenor of the times. Blogs invoke the personal touch and put the character and temperament of the writer out front, rather than disguising it behind a façade of detached objectivity underwritten by the presumed editorial authority of a large formal newspaper or broadcast corporation. Sullivan, whose own blog reaches an estimated quarter of a million readers monthly and has become economically profitable, claims that Net Age readers are increasingly skeptical about the authority of big name media. Many readers know that the editors and writers of the most respected traditional news media are fallible and ‘no more inherently trustworthy than a lone blogger who has earned a reader’s respect’ (Sullivan 2002: 1).

In general, blogs mix comment with links, in varying ratios. Although there are any number of services online that help users create the basic hypertext mark-up language (or HTML) code and ‘look’ of their blogs (e.g., Williams 2002), there is no content formula, and personal style and nature of the topic appear to be key variables in whether a blog privileges commentary or links, or effects some sort of balance between the two. Chris Baker (2002: 1), writing in the same issue of Wired, notes that an index of blogs created at MIT ‘tracks top blogs based on how many people link to them’ (see blogdex.media.mit.edu). Baker identifies a number of current high profile ‘power bloggers’, briefly describes the theme or purpose of their blogs, and reports their respective ratios of comments to links. At one pole of Baker’s selection is the blog of Australian illustrator and web designer, Claire Robertson (www.loobylu.com), which ‘serves up a breezy diary accompanied by exquisite illustrations’, with a ratio of 20 comments to every link posted by Robertson (Baker 2002: 1). At the other end of the spectrum we find the blog of Jessamyn West, the ‘hippest ex-librarian on the Web’ (Baker 2002: 1). West is credited with ‘bringing the controversy and intrigue of library subculture to life’ (Baker 2002: 1) and, not surprisingly, perhaps, provides an average of five links embedded in each commentary.

The vast majority of bloggers, however, are individuals writing for relatively small audiences on themes, topics or issues of personal interest to themselves. Chris Raettig’s popular weblog—currently on hiatus—drew international attention in 2001 with an enormous collection of corporate anthem sound files he had gathered (and had been sent by others) that were, as he put it, ‘so bad, they were good’ (Raettig 2001: 1). At the time, Raettig was a 22-year-old software programmer and developer living in London, and his blog—titled at the time, i like cheese (chris.raettig.org)—features livecam images of his studio apartment; links to a digital photo ‘warehouse’ he has established and which documents everyday moments in his life; hyperlinks to the technology development company he is partner in, the corporate anthem webpage, links to alternative rock music online, and suchlike, along with his journal entries. The principal theme that loosely ties his blog entries together concerns new technologies, with recent entries including commentaries on: the relaunch of his corporate anthems webpage on the zdnet.org website and the renewed international media interest this created, a trip to Cambridge to meet with owners of a technology start-up company, a review of his day, ideas for large-scale internet-based projects, and comments on the current health of the Web industry in general.

At a rather different point on the politico-cultural spectrum we find the blog of Asparagirl, a 23-year-old web designer who works for IBM. Her blog (asparagirl.com/blog) was recently showcased in a Washington Post article on weblogs (Kurtz 2002: 1). It attracts over 1000 daily visitors and presents self-styled ‘solipstic’ commentaries that engage with themes, issues and events such as: the nature of the internet (e.g., issues concerning the joys of interactivity and the need for privacy), issues concerning statecraft and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict written from her perspective as a Jewish-American, meeting other bloggers at a party, the latest bubblegum collector cards that feature victims of the September 11 attacks on the U.S., meta-comments on the content of other people’s blogs, and so on.

(iv) Building Ratings

Since eBay introduced its ratings system for buyers and sellers to rate each other and build up profiles as more or less worthwhile people to do business with online, numerous other spaces on the internet have started using ratings systems as public reputation markers. Plastic is a good example of this, and is somewhat unusual on the internet because it evaluates quality of thinking and expression, rather than business conduct.

Plastic began in January, 2001, with the aim of being a ‘new model’ of news delivery: ‘anarchy vs. hierarchy, and so on and so forth’ (Joey 2001: 1), and promising ‘the best content from all over the Web for discussion’ (Schroedinger’s Cat 2002: 1). This new model of news delivery puts ‘the audience in charge of the news cycle as much as possible without devolving into the kind of ear-splitting echo chamber that’s turned “community” into such a dirty word’ (Joey 2001: 1). Historically speaking, Plastic was the offspring of a merger between Suck and Feed—two popular but culturally edgy content provider web services established in 1995 (Greenstein 2000: 1), combining the quirkiness of Suck newsletters with the insightful and wide-ranging discussions of Feed (cf., Anuff and Cox 1997; Johnson 1997). Plastic was launched in partnership with the editors and services of ten extant and online news and content providers—from Spin, The New Republic, Inside, Movieline, Gamers.com, Modern Humorist, TeeVee, Netslaves, Nerve through to Wired News—helping to choose from among member submissions which news items would be posted on the Plastic website for discussion each day (Greenstein 2001). Plastic decided to go it alone with the help of ‘user-editors’ (Plastic members who act as volunteer submissions editors) in December 2001 after the web service was bought by Carl Steadman—known generically as ‘Carl’ by Plastic users—and who remains chief-Editor and self-appointed site janitor.

The Plastic community comprises anyone and everyone, but judging by the comments posted and the historical and cultural reference points used, the majority of users appear to be male, American, and mostly 20-and 30-somethings. Or, as one anonymous poster described the typical Plastic user:

1. Age: 18 - 35 (Anonymous Idiot 2001: 1) |

In other words, Plasticians tend to be self-styled members of an erudite,

ironic and humorous ‘plugged in’ crowd, interested in quirky takes on

anything newsworthy—particularly anything connected with popular culture—as

well as in serious and informed discussion of current events. Estimates place

the number of regular Plastic users at around 15,000 (McKinnon 2001: 1).

Anything that will provoke discussion is regarded as post-worthy (Carl, in

interview

with Mathew Honan 2001:1).

Although Plastic emulates a long-existing technology news and discussion

website service devoted to a technogeek audience—Slashdot.com—it

is 'new' in

the sense that it turns 'push media' like email-posted newspaper

headlines and news websites on their head by having members propose—and

publicly comment on—content: ‘Plastic’s original contribution

is a forum to discuss the diverse news pieces it promotes. At Plastic, readers’ comments

are what it’s all about’ (Barrett 2001: 1).

Items are written up by users and can be posted to 8 topic categories: Etcetera, Film&TV, Games, Media, Music, Politics, Tech and Work. Those whose news items are accepted for posting and/or who post comments on the website are awarded ratings on two dimensions. One of these is ‘karma’, which is used to rate a participant as an active member of the community relative to the number of newsworthy postings—both in terms of submitting stories and posting comments on stories—she or he has made to the site overall. A karma rating of 50 or over generally elevates the poster to (volunteer) submissions editor status.

The other rating system—which is linked directly to karma—is peer

moderation that operates on a scale of –1 to +5 maximum for a posting

overall. Non-registered posters are allocated a default initial rating of “0” when

they first post a comment, while the rating baseline for registered users is

+1. Moderation points are awarded by Plastic’s editors and by a changing

group of registered Plastic members who have been randomly assigned the role

by Plastic’s editors; or, as the message alerting members to their new

moderator status puts it: ‘Congratulations! You’ve wasted so much

time on Plastic that for the next 4 days we’re making you a moderator’ (Plastic

2002a: 1). Each moderator gets 10 moderating points to award to posted comments

on a Plastic news item, and the possible ratings each moderator can allocate

are:

| Whatever 0 Irrelevant –1 Incoherent –1 Obnoxious –1 Astute+1 Clever +1 Informative +1 Funny +1 Genius +1 Over-rated +1 Under-rated +1 |

The moderation points awarded to each post are tallied and the final score is automatically updated and posted in the subject line of the message for readers to see. In other words, “if four or five moderators think a comment is brilliant, it may end up with a +5; useless comments are moderated down to a –1” (Plastic 2002b: 2).

This ranking practice is based on formal recognition by the site that users cannot read everything that is posted on a topic. With a peer ranking system in place, users can set filters to screen out postings that fall outside a ranking range of their choice. For example, setting the filter threshold at +3 means only those comments that have been moderated and score at or above +3 will be displayed. Conversely, setting the filter threshold at –1 means every commented posted will be displayed. Plastic offers this ranking and filtering function as a means for helping users practise selective reading and to help enhance the quality of postings to the site.

Like the ratings system used on eBay, the moderation and karma system on plastic does not necessarily ensure a harmonious community of users. ‘Meta-discussions’ involving litanies of complaints about being ‘modded down’ unfairly—or being a victim of ‘downmod’ attacks, where a moderator flushes out all your postings and moderates them down regardless of content—are common. One disgruntled user even went so far as to equate downmod attacks with terrorism: Well, to get back to the point I was making, there is a type of attack for which Plastic.com is almost uniquely susceptible. In this type of attack, the terrorist chooses a victim. Then, when he is given the opportunity to moderate, he strikes. He goes through the victim’s list of comments and then, ignoring Plastic’s moderation guidelines, he moderates each of the comments downward. He does not care whether his moderation votes make sense, only that it drives down the rating of the comment. The terrorist’s goal is to drive the victim’s presence on Plastic ‘under the Radar’, below the filtering level of most of the Plastic audience. He also wants to put the victim’s Karma into a nose-dive (Gravityzone 2001: 1).

Others users are accused of being ‘karma whores’ if they appear to be ‘sucking up to’ or worming their way into the favour of Plastic editors in the hopes of getting more stories accepted than other users, or having their comments modded up. As one poster put it bluntly to another, ‘Tyler, kissing Bart’s ass won’t get you more stories posted’ (jbou 2002: 1) in response to Tyler’s post in a heated of discussion of the U.S.’s threats to invade Iraq again. Tyler had written in part: ‘My, we’re feeling self-important today, aren’t we jbou? Could you please point to Bart’s “warmongering” posts? And why should he have to answer to you, or to anyone else, on command?’ (tylerh 2002: 1).

And, despite some posters loudly and repeatedly protesting that they don’t care about their overall karma, karma ratings—and the moderation system—are indeed ‘a new arithmetic of self-esteem’ on Plastic (Shroedinger’s Cat 2002: 1). At stake is public recognition of a poster’s incisive mind, keen-edged humour, ‘innate hipness’, and of being ‘plugged in’ (Plastic 2002a: 1).

Some implications for research

New literacies are complex and diverse. Within education research contexts we need to find ways of researching these literacies that do them justice, that do not water them down, or leach the colour from them. We think that to be useful, the investigation and interpretation of new literacies should involve descriptive, analytic and critical accounts.

Descriptive

The field needs rich descriptive sociological accounts of new literacies. Ideally these will be produced as much as possible by insiders who can ‘tell it like it is practised’—avoiding the risk faced by academic literacy scholars and researchers of getting tripped up on self-conscious allocations to categories. For people like ourselves this might mean that more of our work will assume a kind of ‘brokerage’ role—sifting through what is already available and working to find ways of projecting this work usefully into literacy education and research spaces.

Several years ago, Douglas Rushkoff published his first book, Cyberia (1994). While this has a degree of analysis and comment running through it, it is first and foremost an attempt to describe a world. As a description of a domain of social practice it differs markedly from, say, the kind of account Stephen Duncombe provides of zines (1997). We see both kinds of book playing important roles in informing educational practices generally and literacy education in particular. The kind of account Duncombe provides is work we believe is urgently needed on behalf of the growing range of new literacies. At the same time, we personally learned a great deal from Rushkoff’s book (and his subsequent works) in the way of knowledge of emerging social practices that we think is indispensable for literacy scholars and educators. This included insights into Discourses that are increasingly central to the lives of young people. It also included insights into aspects of subjectivity, identity formation, existential significance, worldviews, etc. as seen from the perspective of participants. This kind of material speaks directly to the sorts of issues raised by educationists who are concerned about things like the presence of aliens in our classrooms (Green and Bigum 1993). Generation X books, such as those written by Douglas Coupland (1991, 1995, 1996, 2000), also provide the kind of verite descriptions educators can learn much from.

We welcome the growing body of work by insiders to ‘new literacies’ and see much value in bringing this work into the gamut of study of new literacies as an important ‘data base’ for dealing with educational issues at the interfaces of work, community, schools and homes (cf., Alvermann 2002; Bruce 2003; Gee 2003; Snyder 2002).

Analytic

Different forms of analytic work are relevant to studying and documenting new literacies. Analytic tools from formal academic and scholarly work might be applied to the kinds of descriptive studies noted immediately above (remembering, of course, that such descriptive accounts will always and inescapably involve a degree of interpretation and analysis). This would involve taking the descriptions as a kind of ‘secondary data’ and making further ‘sense’ of it in various ways. At one level of analysis one might identify and relate the Discourse and discourse aspects of a set of social practices (i.e., the ways of speaking, acting, believing, thinking, etc. that signal one is a member of a particular Discourse, along with the ‘language bits’ of this Discourse; Gee 1996). At a different analytic level, the work might involve a form of sociological imagination (Mills 1959): exploring how subjectivity and identity are related to participation in or membership of Discourses in which new literacies are developed, employed, refined and transformed.

As an example of the kind of analytic work that might be done from the standpoint of sociological imagination we can take a case like David Bennahum’s book, Extra Life: Coming of Age in Cyberspace (1998). Grounded in Bennahum’s experiences of growing up in a digitally-saturated environment, Extra Life has been nicely described by Douglas Rushkoff as a ‘Catcher in the Rye for the Atari Generation’. Bennahum locates computers and computing practices within key phases and events in his adolescence and adult life in New York City. For example, a particular computer teacher, the computing classroom, and experiences in computing class emerge as pedagogical oases in the desert. There is more than a hint that Bennahum’s interest in computing may have helped prevent him going down a road of delinquency and precocity that brought sticky ends to some of his adolescent peers.

Bennahum describes an array of Discourses to which he was apprenticed: for example, the Jewish faith, downtown Manhattan street culture, school and home-based computer nerd culture, teenage sex and romance and, eventually, sophisticated forms of Discourse in cyberspace. From the analytic perspective of sociological imagination, the book provides, among other things, rich data for relating the emergence of a particular kind of symbolic analyst and knowledge worker and the kinds of subjectivity that support creating and maintaining a list like ‘Meme’ to participation in various computing culture Discourses. When the links to Bennahum’s ‘Meme’ list and his home page are taken into account, it is possible to generate and reflect on a diverse range of ideas about how a stratum of the Atari generation builds networks, employs marketing strategies, maintains support systems and so on.

Bennahum is an author, cyber-activist, public intellectual, member of a cyberculture ‘elite’, and a symbolic analyst and knowledge worker of high order and standing. How Bennahum became an insider to particular Discourses, and how this afforded him various ‘tracks’ so far as access to peer groups, employment, and making his way within an emerging global order are concerned, offer some crucial insights for contemporary literacy educators.

With respect to the Discourse-discourse relationship, and a close focus on the language bits within larger social practices, the world of new literacies is rich, varied and readily accessed.

Critical-Evaluative

Two types of critical-evaluative accounts of new literacies seem especially important in relation to literacy education—bearing in mind that, as the outcomes of the practice of critique, ‘critical’ accounts span the range from strongly positive or affirmative to strongly negative or condemnatory.

One type involves taking an ethical perspective toward new literacies, such that we can make sound and fair judgments that have educational relevance about the worth of particular new literacies and the legitimacy of their claims to places within formal literacy programs. The matter of mindsets arises again here. Engaging in critique of new literacies should also be taken as an invitation to examine our own mindset as much as an invitation to judge a practice. The educational literature on practices involving new technologies and, more generally on popular cultural practices, is replete with what seem to us to be straightforward dismissals of new ways of doing and being from the standpoint of unquestioned outsider perspectives. Such critiques are more likely to obstruct than enable progress in curriculum and pedagogy. On the other hand, the kind of critique of the D/discourses involved in the design and production of a particular range of computing games provided in Allucquère Rosanne Stone’s chapter on ‘Cyberdämmerung at Wellspring Systems’, in her book on The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age (1996), may be invaluable for literacy educators. Stone provides a stunning account of life inside an electronic games production sweatshop. The chapter disrupts concepts like ‘symbolic analysis’, presents a new line on what lies behind the text, and takes a sober look at the theme of gender and power in the world of new technologies.

The second kind of critique we have in mind involves taking a curriculum and pedagogy perspective based on the criterion of efficacious learning. From a sociocultural perspective,

the focus of learning and education is not children, nor schools, but human lives seen as trajectories through multiple social practices in various social institutions. If learning is to be efficacious, then what a child or adult does now as a learner must be connected in meaningful and motivated ways with ‘mature’ (insider) versions of related social practices (Gee, Hull and Lankshear 1996: 4).

For literacy education to be soundly based, we must be able to demonstrate the efficacy of any and every literacy that is taught compulsorily. This, of course, immediately questions the basis of much, if not most, of what currently passes for literacy education. The criterion of efficacy applies very strongly to attempts to promote new literacies in classrooms. As we have argued elsewhere (Lankshear and Knobel 2003; Lankshear and Snyder 2000; Goodson, Knobel, Lankshear and Mangan 2002), efforts to incorporate new ICTs into language and literacy education are often misguided from the standpoint of efficacious learning. Often they enlist learners in characteristically ‘schoolish’ practices that have little or no present or future purchase on life outside the classroom.

Using the schema

To identify some possible implications of ‘new’ literacies (of the kinds we have described) for writing research, a useful way to proceed is by taking the ‘logic of research’ schema we began with and addressing the question of implications to its various components. For example, we might ask what some possible implications might be for research purposes and/or research questions in the area of writing of the kinds of literacies we have tried to describe. We can ask what might some implications be for the literature we read and the kinds of frameworks we develop for our work in writing research as a consequence of the emergence of such ‘new’ literacies (and the many others we have not addressed). And likewise for data collection/analysis and so on.

There is neither time nor space to go into this in detail here and, in any event, the more valuable task is to indicate an approach to going about the business at hand that others might take up rather than trying to conduct the business oneself. Local conditions and contexts will impact greatly on the kinds of emphases that are most pertinent to particular cases. At the same time, we feel obliged to indicate briefly a few of the aspects that have occurred to us in the course of working within this field.

A comment on research purposes

In the light of the kinds of examples we have given, a researcher might conclude that some of these literacies are valuable and important in ways to which school-based learning should be accountable, and that conspicuous as they are by their absence in regular classroom programs a worthy research purpose might involve conducting some kind of intervention study. This would be a study that approaches the research as a pretext for trying to implement some ‘new’ literacy in as authentic a manner as possible and to investigate rigorously what happens with respect to writing practices.

In such a case it would be crucial to avoid as far as possible the ‘schoolification’ of the practice in question, mindful of the tendency for schools and classrooms to remake all social practices in their own image. Recently, we have become involved with supporting the development of a small scale approach called ‘knowledge producing schools’ (KPS). This is emerging as an alternative to systemic level attempts at reform along the lines of ‘New Basics’ that appear to be encountering the kinds of demands for moderation and accommodation to state performativity measures and adherence to the modernist space of enclosure that is the classroom that, precisely, define an education system (see Bigum 2002 in particular). Under these conditions many of the kinds of activities mobilised as ‘Rich Tasks’ quickly end up looking like the kinds of ‘pretend’ exercises so prevalent in schooling (see Figure 5, for example).

| Years [Grades] 7-9 Rich Task #1 - Science and Ethics Conference Students will identify, explore and make judgments on a biotechnological process to which there are ethical dimensions. They will identify scientific techniques used, along with significant recent contributions to the field. They will also research frameworks of ethical principles for coming to terms with an identified ethical issue or question. Using this information, they will prepare pre-conference materials for an international conference that will feature selected speakers who are leading lights in their respective fields. |

Source: http://education.qld.gov.au/corporate/newbasics/html/richtasks/year9/year9.html

Figure 5: An example of a Years 5-9 Rich Task.

In contrast, the Knowledge Producing Schools approach begins from the assumption that education is an ‘all of community’ responsibility. It strives to forge links between the school and the community in order to build an identity around the concept of the school being an effective and capable producer of knowledge for its community. At the same time, it looks to the community for opportunities to live out this identity authentically and for sources of expertise and other resources integral to performing its mission well. The schools take on (in the manner of research consultants) real tasks from the community (as well as of their own concern and formulation) and commit to performing them as effectively as any competitor from the ‘real world’ might. Hence, one primary school in Central Queensland, Australia, that has earned a reputation for digital video editing and production is receiving commissions from local organisations and enterprises to design and produce public relations documents and news artifacts from original footage, supplemented by new footage they conceive and shoot themselves. They acquired this expertise by ‘apprenticing’ a group of grade 5 and 6 students to a professional producer who happened to be the sibling of a teacher trainee getting field practice in the school. The model has become general throughout the school, with 9 year olds offering professional development to school principals on a range of technological applications, and students and community members jointly researching traffic speeds through the area at ‘sensitive’ times of the day and demonstrating the need for speed zone changes (subsequently acted on by the local transport authorities).

Against such a background it is, for example, very easy to envisage an intervention study based around an opportunity to, say, undertake a scenario building/planning activity for a community or community organisation inspired by an authentic need or issue. The research could include a training phase in which students (perhaps in collaboration with community personnel) became proficient in the theory and conduct of scenario planning, followed by a phase in which the scenario planning team undertook the work. The research could, perhaps, be designed and conducted as a rigorous action research project genuinely committed to knowledge production of the kind of sophistication described by people like Wilf Carr and Stephen Kemmis (1986)—as opposed to the shonky action research implementation-only exercises so beloved of education administrations bent on incorporating teachers into the latest preferred fad. The all-important and creative narrating dimension could, perhaps, become a particular focus from the standpoint of writing research. So might the reporting of the project as a whole by the participants, the subsequent take up, and so on.

A note on literature

Perhaps the most obvious implication for writing research with respect to ‘the literature’ is that ‘subsets’ of literature that are quite unconventional from a traditional writing research perspective might become absolutely central to informing and framing the study. An excellent up to the minute example is provided in James Paul Gee’s current book on the theme of what video games have to teach us about literacy and learning (2003). For Gee, the games manuals often assume a role as vital and demanding as the literature he draws on from situated cognition, connectionism and literacy studies. In the case of our own work we have often found sources like Where Wizards Stay up Late (Hafner and Lyon 1996), Cyberia (Rushkoff 1994), and even magazine articles like ‘The cyberspace cowboy’ (an interview with John Perry Barlow; see Tunbridge 1995), among many others, to be much more useful for understanding issues, formulating questions, developing a conceptual and theoretical framework and framing data collection and analysis designs and tools than trawling one more time through the annals of the New Literacy Studies.

A note on data collection and analysis: notes from the field

The relative accessibility of online communities and literacy practices has made researching new literacies—like those we described earlier—an increasingly popular option for education researchers. Researching new literacies generally takes one of four forms:

| New literacies research conducted within ‘virtual realities’ or cyberspaces | |

| Research conducted about ‘virtual realities’ and new literacies | |

| Research that spans ‘virtual realities’ and meatspaces | |

| Research that has some ‘virtual reality’ component (e.g., information gathering, supplementary texts in the form of relevant interviews, reviews, images, discussions, one aspect of a person’s literacy practices in a given day, etc.). |

New literacies research conducted within ‘virtual realities’ (which includes computer and video games, as well as the internet, mobile phone communication, and the like) refers to studies that are conducted entirely within a virtual space, such as collecting interactional data within an online, three-dimensional multi-player game world (e.g., Ultima II, Everquest) or discussion-based communities (cf., our earlier description of Plastic.com) (cf., Hine 2000; Jones 1999. Research conducted entirely online is facilitated by software that records interactions, by saving txt-based discussion to one’s hard drive, or by printing out one’s data. As we document elsewhere (see Lankshear and Knobel 2002), little on the internet can be relied on to remain exactly as it was when first encountered; as such, the online researcher soon learns to make copies of data to be analysed in order to obtain a data set that can be revisited any number of times.

Research conducted about ‘virtual realities’ and new literacies includes documenting new literacy practices that have emerged online. Weblogs and blogging are an example of this kind of research. The immediacy of weblogs, their use of hyperlinks, their networks of connections makes weblogs one of the earliest ‘truly new’ literacies to emerge online (cf., Blood 2002). Researching literacies online is aided by a number of tools and services online that users employ to judge the popularity of, or traffic to and from, different websites and weblogs. These include:

| aggregators—programs that that tally the number of times a weblog or website has been linked to by others in order to judge its popularity, saliency, controversy level, and so on; | |

| indices, portals and webrings that act as useful starting places when exploring literacy practices online (e.g., indices can be lists of zines or weblogs online, portals can act as jumping off places into new topics or interests for newcomers, and webrings are formal networks of online spaces that share common themes and interests). |

These services enable education researchers to sample and locate data easily, and can help make manageable the need to scan vast amounts of information on a regular basis. Perhaps most useful, however, is the way in which aggregators pick up on trends, new memes, and can be used to trace the ways in which information is shared, used and distributed.

Research that spans ‘virtual realities’ and meatspaces provides important insights into what people do offline when they are interacting, working and the like online. It also helps to contextualize studies of online communication use, such as email, instant messenger services, chat spaces, blogging, and the like (cf., Leander and Johnson 2003; Thorne 2003). This approach to research, as explained by Kevin Leander and Kelly Johnson, requires quite complex data collection methods that often include: online tracking software to gather data about the study participants’ internet use, video and in-person observation data of the participant using the computer and internet, online and offline interviews with participations, and so on. Data analysis requires the researcher to carefully triangulate and cross-reference multiple sources of data in the process of building rich interpretations of what it is that people ‘do’ when using engaging in new literacy and new technology practices.

Research that has some ‘virtual reality’ component is perhaps the most common approach where digital data and education are concerned. This approach to research documents study participants’ computer gaming, internet uses, computer uses and the like as one part of a broadly construed research project. For example, in previous work we helped to set up small clusters of students, cultural workers, technology experts and teachers who worked together on a computer-based project. While computer use was an important part of the study, it was by no means the sole focus of our investigations, which also included documenting by means of video taping and observation fieldnotes, artifact collection, and semi-structured interviews with participants students’ interactions with each other and with participating adults, students ways of speaking about themselves as computer users, analyzing school appropriations of new technologies, and so on (see Rowan, Knobel, Bigum and Lankshear 2002; Goodson, Knobel, Lankshear and Mangan 2002).

In addition, Torill Mortensen and Jill Walker (2002) are currently documenting the development and use of weblogs as research tools. Mortenson and Walker both conduct much of their own research online, and each began a weblog as a way of reminding themselves what their study focus was at the time. These weblogs, however, soon “developed beyond digital ethnographer’s journals into a hybrid between journal, academic publishing, storage space for links and site for academic discourse” (p. 250). Thus, blogs may well become important indices to and evidence of personal and collective knowledge structures by both recording and unveiling an individual’s or a group’s knowledge or epistemic effort over time.

Conclusion

We believe the implication of ‘new’ literacies for writing research

are many and varied and, moreover, that following them can provide us with

opportunities to realise what is, perhaps, the highest calling of research

under contemporary conditions and, not surprisingly, modelled par excellence

in the very gestation and incubation halls of the ‘new’ literacies—places

like the MIT Media Lab, online gaming spaces, and other locations where

wizards stay up late: namely, the productive pursuit of serious fun.

References

Alvermann, D. (Ed.). (2002) Adolescents and Literacies in a Digital World. New York: Peter Lang.

Anonymous Idiot (2001) Typical Plastic member profile. Plastic.www.plastic.com (accessed 10 Feb. 2002).

Anuff, J. and Cox, A. (1997) Suck: Worst-Case Scenarios in Media, Culture, Advertising, and the Internet. San Francisco: Hardwired.

Baker, C. (2002). Power bloggers. Wired. May. 10.05. www.wired.com/wired/archive/10.05/mustread.html?pg=3 (accessed 20 Apr. 2002).

Barrett, A. (2001) Plastic.com Invites Visitors to Shape the Site. PCWorld.com. Monday, January 22. www.pcworld.com/news/article/0,aid,39013,00.asp (accessed 10 Feb. 2002).

Bigum, C. (2002) Design sensibilities, schools and the new computing and communication technologies. In I.Snyder (Ed.) Silicon Literacies: Communication, Innovation and Education in the Electronic Era. London: Routledge. 130-140.

Bennahum, D. (1998) Extra Life: Coming of Age in Cyberspace. New York: Basic Books.

Blood, R. (2002) Introduction. In Editors of Perseus Publishing (Eds.). We’ve Got Blog: How Weblogs are Changing Culture. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. ix-xiii.

Bruce, B. (2003) Literacy in the Information Age: Inquiries into Meaning Making with New Technologies. Newark, DEL: International Reading Association.

Carr, W. and Kemmis S. (1986). Becoming Critical. London: Falmer Press.

Coupland, D. (1991) Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Coupland, D. (1995) Microserfs. New York: HarperCollins.

Coupland, D. (1996) Polaroids from the Dead. New York: HarperCollins.

Coupland, D. (2000) Miss Wyoming. New York: Pantheon.

Cowan, J. et al. (1998) Destino Colombia: A scenario process for the new millennium. Deeper News. 9(1): 7-31.

Duncombe, S. (1997) Notes From Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. London: Verso.

Gee, J. P. (1996) Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses. 2nd edition. London: Falmer.

Gee, J. P. (2000) Teenagers in new times: A new literacy studies perspective.Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. 43 (5): 412-23.

Gee, J. P. (2003) Literacy and Learning in Video and Computer Games. New York: Palgrave.

Gee, J. P., Hull, G. and Lankshear, C. (1996) The New Work Order: Behind the Language of the New Capitalism. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Goodson, I., Knobel, M., Lankshear, C. and Mangan, M. (2002) Cyberspaces / Social Spaces: Culture Clash in Computerizes Classrooms. New York: Palgrave Press.

Gravityzone (2001) ‘Terrorist’ Strikes Plastic.com—Editors Helpless. Plastic. www.plastic.com (accessed 13 Feb. 2002).

Green, B. and Bigum, C. (1993) Aliens in the classroom. Australian Journal of Education. 37(2): 119-41.

Greenstein, J. (2000) Feed and Suck link up. The Industry Standard. www.thestandard.com/article/display/0,1151,16708,00.html (accessed 10 Feb. 2002).

Hafner, K. and Lyon, M. (1996). Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet. New York: Touchstone.

Hine, C. (2000) Virtual Ethnography. London: Sage.

Honan, M. (2001). ‘Plastic is all I do’. Part 2: Plastic’s Return. Online Journalism Review. www.ojr.org/ojr/workplace/1017862577.php (10 Feb. 2002).

Hull, G., Jury, M. and Katz, M. (1998) Working the Frontlines of Economic Change: Learning, Doing and Becoming in the Silicon Valley. Berkeley, CA: Graduate School of Education.

jbou (2002). ‘I was wrong about Bart …’, Plastic. www.plastic.com (accessed 13 February 2002).

Joey (2001) Anatomy of a Plastic Story. Plastic. www.plastic.com (accessed 10 February 2002).

Johnson, S. (1997) Interface Culture: How New Technology Transforms the Way We Create and Communicate. San Francisco: HarperEdge.

Jones, S. (Ed.) (1999) Doing Internet Research: Critical Issues and Methods for Examining the Net. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kurtz, H. (2002). Who cares what you think? Blog, and find out. Washington Post. 22 April. C01. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A25512-2002Apr21.html (accessed 22 Apr. 2002).

Lanham, R. (1994) The economics of attention. Proceedings of 124th Annual Meeting, Association of Research Libraries. Austin, TX, May 18-20

Lankshear, C. and Knobel, M. (2002). Young Children and the National Grid for Learning. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. 2(2): 167-194.

Lankshear, C. and Knobel, M. (2003). New Literacies: Changing Knowledge and Classroom Learning. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Lankshear, C. and Snyder, I., with Green, B. (2000) Teachers and Technoliteracy: Managing Literacy, Technology and Learning in Schools. St Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Leander, K. and Johnson, K. (2003) Tracing the everyday ‘sitings’ of adolescents on the Internet: A strategic adaptation of ethnography across online and offline spaces. Education, Communication and Information. 3(2) (in press).

McKinnon, M. (2001). One Plastic Day. Shift Magazine. 9(4): 1-3.www.shift.com/toc/9.4 (accessed 10 Feb. 2002).

Mills, C. Wright (1959). The Sociological Imagination. London: Oxford University Press.

Mortenson, T. and Walker, J. (2002). Blogging thoughts: Personal publication as an online research tool. In A. Morrison (Ed.), Researching ICTs in Context. Oslo: Intermedia Report. 249-279.

Plastic (2002a) www.plastic.com (accessed 21 Mar. 2002).

Plastic (2002b) Guide to Moderating Comments at Plastic. www.plastic.com/moderation.shtml (accessed 13 Feb. 2002).

Raettig, C. (2001a) Analysis and thoughts regarding kpmg (warning: maximum verbosity!). Chris Raettig—Personal Website. chris.raettig.org/email/jnl00040.html (15 January 2002).

Rowan, L. and Bigum, C. (1997) The future of technology and literacy teaching in primary learning situations and contexts. In C. Lankshear, C. Bigum et al. (investigators) Digital Rhetorics: Literacies and Technologies in Education—Current Practices and Future Directions, Vol. 3. Children’s Literacy National Projects. Brisbane: QUT/DEETYA.

Rowan, L., Knobel, M., Bigum, C., and Lankshear, C. (2002). Boys, Literacies and Schooling: The Dangerous Territories of Gender Based Literacy Reform. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Rushkoff, D. (1994) Cyberia. Life in the Trenches of Hyperspace. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

Schroedinger’s Cat (2002) First Plastiversary—Happy Birthday, Plastic! Plastic. www.plastic.com/article.pl?sid=02/01/09/0235209&mode=thread&threshold=0 (accessed 15 Jan. 2002).

Schwartz, P. (1991) The Art of the Long View. New York: Doubleday.

Snyder, I. (Ed.) (2002) Silicon Literacies: Communication, Innovation and Education in the Electronic Era. London: Routledge.

Stone, A. (1996) The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Street, B. (ed.) (1993) Cross-Cultural Approaches to Literacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sullivan, A. (2002). The blogging revolution. Wired. May. 10.05. www.wired.com/wired/archive/10.05/mustread.html?pg=2 (accessed 20 Apr. 2002).

Thorne, S. (2003). Artifacts and cultures-of-use in intercultural communication. Language Learning and Technology. 7(2): 38-67.

Tunbridge, N. (1995) The cyberspace cowboy. Australian Personal Computer, September: 2-4.

tylerh (2002) ‘My, we’re feeling self-important today….’ Plastic. www.plastic.com (accessed 13 Feb. 2002).

van der Heijden, K. (1996) Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation. Chichester: Wiley.

Wack, P. (1985a) The gentle art of reperceiving. Harvard Business Review. September-October. 73-89.

Wack, P. (1985b) Scenarios: Shooting the rapids. Harvard Business Review. November-December. 139-150.

back to work index / to AERA 2003symposia index / back to main index