Do-It-Yourself Broadcasting: Writing Weblogs in a Knowledge Society

Colin Lankshear and Michele Knobel

AERA 2003, Chicago, April 21.

Introduction

The practice of weblogging—or “blogging”, as it is popularly known—has gone through a series of growth spurts during the past 4 years. Two recent developments in particular provide a background for this paper. These are the acquisition of Blogger.com by the search engine giant, Google, and the increasingly easy access to free and user-friendly blogging software and server host space, such that anyone can operate their own blog for the price of accessing an internet service and the time and creative energy it takes to establish and maintain a blog.

In this paper we will briefly describe blogging as an online practice that takes numerous forms, and consider two or three of the windows it provides on contemporary educational practice. We will begin with a brief overview of setting up a basic blog, and distinguish some different types of blogs in terms of their “look” and “feel”. We will then consider blogging in relation to some ideas about “powerful writing” that have been more or less influential in recent years and consider some limits of metacognitivist educational applications in the light of what we say. Then finally, we will consider the notion of blogs as “backup brains” in relation to social practices mediated by writing.

Blogs and Blogging

Blogging history

Weblogs have existed online for almost a decade. However, it wasn’t until the second half of the 1990s that weblogs began to grow in popularity. Weblogs—or “blogs” for short—began as websites that listed annotated hyperlinks to other websites containing interesting, curious, hilarious and/or generally newsworthy content located by the publisher of the weblog. These blogs generally are the result of wide-ranging online and offline research and often provide alternative perspectives on a topic or issue. Rebecca Blood—a popular and long-time weblogger—describes this use of weblogs in terms of skilled researchers filtering internet content in “smart, irreverent, and reliably interesting” ways (Blood 2002a: ix).

The release of online publishing tools and web hosting services, Pitas.com and Blogger.com, in 1999 made weblogging much more accessible to internet users not overly comfortable with working in hypertext markup language to code and design their own weblogs. While early blog publishers—generally known as “bloggers”—were largely from the tech world, this new generation of bloggers was much more diverse. Many began using weblogs as something more akin to regularly updated journals than to indices of hyperlinks. Entries in these weblogs document everything from what the blogger had for lunch that day; movie and music reviews; descriptions of shopping trips; through to latest illustrations completed by the blogger for offline texts; and the like. Many weblogs now are hybrids of both, or a mix of musings or anecdotes with embedded hyperlinks to related websites. Blood describes this new use of weblogs as one concerned with creating “social alliances” (Blood 2002a: x). That is, the weblogs are largely interest-driven and attract readers who have (or would like to have) similar, if not the same, interests and affinities.

At present, a weblog is best defined as “a website that is up-dated frequently, with new material posted at the top of the page” (Blood 2002b: 12). There are no hard and fast rules for weblogs. In general, each weblog entry is short and accompanied by the date (and sometimes the time) it was posted, in order to alert readers to the “currency” or “timeliness” of the log. Some bloggers choose to update several times a day, while others may update every few days or once a week or so.

Anatomy of a weblog

There are no hard and fast rules for what a weblog should look like; nevertheless,

most weblog front pages are divided into at least two columns (see Figure 1).

One column houses each weblog posting, ordered chronologically from the most

recent entry to the least recent entry with entries archived after a given

period (e.g., a few days, a week, a month). The second column acts as an index

of hyperlinks

to the blogger’s favourite, somehow related, or recommended websites and

weblogs. This index is usually divided into sub-categories and generally runs

along lines of interest. For example, Aaron Swartz—a popular teenage and

long-term blogger—has organised his index of links into the following

categories: quick links, more me (linking to additional websites published

by Aaron), friends,

art, news, and tech news.

Figure 1: Typical weblog layout (weblog.quartzcity.net)

Blog posts tend to be relatively short—in general, no more than a few lines to each post. There are basically two types of posts: those that include hyperlinks to other blogs or websites, and those that don’t. Those posts that do include hyperlinks may begin with a link and post comments beneath it, in a form very similar to an annotated bibliographic entry. Hyperlinked posts may also include quotes from the information or text to which they are linking—in the manner of a “sound bite”—in order to give readers a sense of what they will find when they follow the link.

Additional weblog features can include:

Setting up a blog

Establishing a personal weblog is a relatively straightforward progress—and

can be done in about 10 minutes. As preparation for writing this section we

undertook the process of setting up a minimalist blog and documenting the steps

involved

(although we began from a situation of broad familiarity with the look and

feel and purposes of a diverse array of weblogs.)

Perhaps the easiest way is to use one of the free online weblog building services,

such as Blogger.com, Livejournal.com or

Pitas.com. In the case of Blogger.com, for example, setting up a new weblog involves

a simple

6-step process. The

first step involves registering with Blogger.com by selecting a username and

password

and entering them into the appropriate fields. The second step requires the

weblogger to confirm that he or she will abide by Blogger.com’s user agreement, and

provides the user with the opportunity to subscribe to the service’s regular

newsletter concerning service developments and the like. Step 3 marks the beginning

of the actual blog “building” process. The user is asked to decide

on a title for the blog (in our case, we chose, “Everyday Literacies”)

and to write a descriptive summary of the purpose or nature of the blog. In

our case, the description we settled on reads:

Explores and comments on everyday practices of producing and consuming texts of whatever kind in meatspace and cyberspace.

Step 4 involves the user choosing between free blog hosting on Blogspot.com, or to use their own server space to host their blog. In other words, Blogger.com is used to generate and edit the blog, and free hosting services such as Blogspot.com or a private server post the blog for viewing by others. Where users have elected to have their blog hosted on Blogspot, they are asked in Step 5 to nominate an “address” for the new blog, which will become part of the web address for locating the blog. In our case, we decided up “everydayliteracies” as our address, which generated the following internet location for our new blog: http://everydayliteracies.blogspot.com. In the sixth and final step, users choose an interface template for their blog—which will determine the layout of the blog, colours used, and the way in which the text of each blog posting is displayed, where additional link indices are located on the main webpage and the like.

These 6 steps generate a basic blog. Blogger.com also enables users to edit the HTML code of the templates they provide. This means that a working knowledge of hypertext markup language (HTML) enables users to “tweak” the template they have selected for their blog to include lists of related or favourite websites and other blogs, to change font styles and sizes, to change background colours, and so on. In our case, we added in a subtitle, “Salient websites” and included beneath it a list of web addresses related to our “everyday literacies” theme. We also shifted and added bold to some sub-headings to improve the overall look of the blog page (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: setting up a weblog (http://everydayliteracies.blogspot.com)

A key component of weblogs is the option for readers to post comments on each

weblog entry. Blogger.com does not include this feature in their platform at

this point, but recommends third-party comments hosting services—such

as Enetation.co.uk

and Blogout.com. Enetation.co.uk, for

example, provides bloggers with the HTML codes to insert

into their posts that will

add a “comments” link to each entry. When readers click on this

link, they are actually posting to the entertate.co.uk server although the

comment

appears to be part of the weblog itself and located on the same server as the

weblog.

Typology of weblogs

Blogging has evolved into diverse forms. Some of the range is captured in the following figure (Figure 3) of a preliminary taxonomy of weblogs.

Blogs as a window on “powerful writing”

During the past 10-15 years various pedagogical approaches to making students more powerful writers have been proposed for classroom use. For example, an appropriation of systemic functional linguistics known in Australia and beyond as “genre theory” proposed that if learners understood the features of a range of genres they could mobilize the genres in ways that would enable them to realize their purposes more powerfully (e.g., Christie 1987, Martin 1993, Martin and Rothery 1993). This led to the development of genre-based curricula (or curriculum components) for literacy education/English programs in places like Queensland and New South Wales (in Australia). Very briefly, the idea was that certain genres—e.g., Narrative, Procedure, Transaction, Exposition—could be taught at particular points in the curriculum. Through genre-based literacy pedagogy learners would be encouraged to understand the key features of these genres, when a specific genre was appropriate, and how to actually produce specific text-types within ach genre (e.g., within the transaction genre, how to produce invitations, letters of complaint, conduct interviews etc. as needed). The reasoning here seemed quite compelling to many people—mastery of genres would make individuals and groups more powerful language users better able to achieve their purposes through language. Classroom pedagogy appropriations of critical literacy, critical media literacy, and the like provide other examples. To date the evidence for the efficacy of any of these initiatives is sketchy at best. On the one hand, their actual pedagogical applications have typically been less than convincing. On the other hand the question arises as to how far and under what conditions the capacity to employ genres or critical literacy would actually be empowering if learners were indeed to master them.

Blogs provide some interesting angles on such questions, particularly from the perspective of power in relation to language in the context of “an information society” where, potentially, our use of “written language” (broadly conceived) can reach larger audiences than could ever have been imagined even a decade ago. In this section we interact with a recent paper by Clay Shirky (2003) and argue for a series of points we believe are relevant and, indeed, important to issues of power in relation to writing pedagogy.

Shirky (2003) addresses powerful blogging in terms of laws of distribution linked to choices and preferences among diverse options. He notes that an “A-List” of extremely high profile bloggers has emerged and, to a large extent, consolidated. Of course, the A List phenomenon has been an abiding theme on the internet since its inception. (It has its correlates in the material world as well—as in the 80-20 rule with respect to income/wealth). This concerns the fact that a relative few (websites, bulletin boards, MUDs [multi-user domains], online communities and, now, blogs) account for the majority of traffic/“hits”. In the case of weblogs, an ongoing project by N. Z. Bear (www.myelin.co.nz/ecosystem/) has arranged more than 400 weblogs in rank order by the number of inbound links they have (that is, the number of other weblogs that link to them). (Lists and counts of inbound links are available via aggregation services, like blogdex.com, popdex.com, daypop.com). Of 433 blogs the 2 top ranked accounted for 5 percent of inbound links, the top 12 for 20 percent and the top 50 (or 12 percent of the total sample) accounted for 50% of the inbound links.

The graph for inbound links tracked by N.Z. Bear and reported by Shirky in

the first quarter of 2003 is as follows.

Figure 4: Weblogs and power law distribution (From: Shirky 2003: 2).

Shirky sees this phenomenon as an example of “power law distributions”.

A key idea here is that in any system where many people are free to choose

between many options, a small subset of providers will attract a disproportionately

large amount of the choices exercised. They will thereby attract disproportionately

large amounts of related “good” or “benefit”: such

as internet traffic, wealth, attention, and so on. According to Shirky, “the

very act of choosing, spread widely enough and freely enough, creates a power

law distribution” (ibid: 1). The greater the diversity of options the

steeper the curve. Increasing the size of the system (the number of choices)

increases the size of the gap between #1 and the median, rather than flattening

the curve—as we might intuitively expect if we worked simply from a presumption

of statistical probability. Within such distributions the great majority is

always well below “average” because the curve is always skewed

so strongly in favour of the “top performers”.

Power law distributions lose their (statistical) counter-intuitivity if we assume that any option chosen by one chooser is more likely—even if only by a tiny amount—to be chosen by another chooser. This involves the idea that choices are not literally “free and unaffected.” Rather, they are influenced by choices previously made by others (or what Shirky (ibid: 4) calls “a preference premium” shaped by positive feedback). Within free and diverse systems, “any tendency toward agreement, however small and for whatever reason, can create power law distributions” (ibid.). Tendencies toward agreement that lead us to “invest in” or “choose for” some particular option might arise for all kinds of reasons. For example, the option in question might simply be of such high quality or compellingness that we, along with many others, “automatically” or “intuitively” gravitate toward it, or pick it up. Alternatively, the factor might be that one’s friends, peers, etc., choose X, or we may be aware of X because it has been written up in some publication we take seriously, and so on. The actual reasons are not all that important. What is important is the capacity of tendencies toward agreement to create power law distributions.

The question that interests us here is how such considerations might apply to the matter of powerful writing: how we might conceive powerful writing, how we might strive to write powerfully or assist others in learning how to write powerfully and compellingly. We find Shirky’s perspective simultaneously illuminating and troubling in this regard. Above all, however, we believe he is highlighting phenomena literacy educators need to reckon with.

Above all, Shirky reminds us of is that we are now living under the sign of information—as in “information technologies”, “information society”, “information age”, etc.—and we are equally living under the sign of markets. Indeed, information is a market par excellence. Whether we like this or not—and personally we have some serious misgivings about where markets can lead—the fact is that the market ideology is currently hegemonic, and will be for the foreseeable future. Consequently, even while we may act as much as we can to resist market ideology and market-driven practices, we will for the foreseeable future nonetheless be living under the prevailing rule of markets. And whatever else it might mean to be powerful in one or another aspect or domain under such conditions, it most certainly implies getting significant, or enough, “market share”. To be influential means gaining purchase or edge in the market of ideas. From this standpoint, powerful writing will be a function, in the first instance, of achieving success in some market or other. This is why blogs are especially significant so far as offering a contemporary window on powerful writing is concerned. Blogs are most emphatically operating under market conditions and are widely being written and thought about as such.

In the burgeoning and over-saturated information market inhabited by blogs, power laws are readily apparent if we equate “power” with such indicators as attracting many hits, inbound links, comments from readers, and gaining a lot of attention (as indicated by numbers of mentions, and “near-the-top-of-the-list” positions in key word searches and aggregator tallies), and so on. Consequently, within the information market, being a powerful writer might be equated quite simply with scoring well on such indicators. In the case of blogs specifically, the association between writing and power is most readily rendered in terms of inbound links, which can be understood as transfers of attention to the blogger by other people (cf. Goldhaber 1997, 1998).

In this context Shirky makes some interesting observations so far as powerful writing and being or becoming a powerful writer are concerned. We will note some of these and trace their implications.

First, Shirky claims that under operating conditions of freedom and diversity the kind of “inequality” reflected in the Blog Power Law Graph is more or less “fair” in the sense that almost anyone with the desire to do so can get access to putting their fare on the market. Moreover, under such “open access” conditions only enormous “artificial” intervention and regulation could reverse this trend toward inequality.

Second, Shirky observes that it is relatively harder for latecomers than earlycomers to become “stars”. This is because in addition to being noticed and “picked up” by others they actually have to work against preference premiums that are already in place. In other words, they do not come into a genuinely free and open market, or onto a truly level playing field, because there are already “tendencies toward agreement” operating.

Third, Shirky acknowledges that there are “doubtless [many bloggers]

who are as talented and deserving as the current stars, but who are not getting

anything like the traffic [of the stars]” (ibid: 5). Moreover, he says,

this trend will only intensify in the future.

Shirky’s fourth observation is particularly interesting. He suggests

that the “top” and “tail” of the social order of bloggers

will correlate very closely with different types of activity: with different

forms of blogging. The typology of blogs we have provided comports well with

Shirky’s observation that (if it has not already happened) “weblog

technology will be seen as a platform for so many forms of publishing, filtering,

aggregation, and syndication that blogging will stop referring to any particular

coherent activity” and the “head and tail of the power law distribution

[will] become so different that we can’t think of J. Random Blogger and

Glenn Reynolds of Instapundit as doing the same thing” (ibid).

Shirky says those at the “head” will in effect be mainstream media

types: that is, “broadcasters”. They will be generating so much

traffic they will have no time to correspond/converse/communicate. They will

simply be “putting out”. By contrast, the long “tail” of

webloggers will be the personal journal/conversational types writing for a

few friends and engaging with them via their blogs.

In between these extremes will be blogs intended to involve their creators

in “relatively engaged relationships” with “moderate sized

audiences” (ibid.). These might be blogs that, say, professional specialists

create in order to galvanise an affinity group in which they will play key

or leading roles.

Such observations suggest a range of implications for “powerful writing”. We will briefly note some of these here before turning to other insights the world of blogs has to offer writing pedagogy.

First, the different forms of blogging distinguished by Shirky as corresponding to the top, middle and tail of the social order of bloggers may be associated with quite different concepts of powerful writing, and of experiencing oneself as a powerful writer. Within the blogosphere “powerful writing” becomes highly ambiguous. If we take the “top” as representing what it is to be a powerful writer—the full-blown market model—then powerful writing consists in attracting disproportionately large numbers of inbound links. At the other extreme, however, if we take construct a concept of powerful writing based on the “tail” of the blogger order, then experiencing power as a writer might come from “publishing an account of your Saturday night and having your three closest friends read it [so that] it feels like a conversation” (Shirky, ibid.). This would be particularly so if these friends posted comments on your blog and/or followed up on their blogs with accounts of their own Saturday nights (ibid.).

Second, if we take the model of the number of inbound links as an indicator of power, then powerful writing may have a lot to do with writing out of some already advantageous position. In the blogging world, Andrew Sullivan shows up at the top or near the top of most versions of the A-list. Before he took to blogging and began to champion blogging as potentially the next powerful form of journalism, Sullivan had achieved a strong reputation as a columnist for the New York Times. On the one hand, this might be taken as evidence that being a powerful writer (in one public domain or one social form of writing) begets power in another. On the other hand, however, it seems highly likely that a successful sportsperson would stand a spectacularly good chance of becoming a powerful blogger/writer/author on the inbound hits model even if, on many measures, s/he were barely literate! Indeed, the media and information market is awash with such examples.

Furthermore, given the power law distributions operating in writing markets

like the blogosphere, excellent (let alone competent) performance in terms

of the kinds of qualities manifested by the most popular writers is no sure

passport to power or to powerful effects – save in a tiny minority of

cases. Being as talented and deserving as the “stars” may count

for little or nothing on its own.

Third, Shirky’s “middle” of the blogging order, based on

involvement in relatively engaged relationships with a moderately substantial

audience suggests the important role that might be played by membership of

an affinity or identity group in achieving power as a writer. If one’s

blog (or whatever medium) can be established as representing or serving a constituency,

identity/affinity group, etc., one is likely to generate many more “hits” and

inbound links, and/or mobilise more attention and influence, than one could

if saying the same thing the same way as a “free-standing” individual.

Alternatively, a blogger operating in this middle range might achieve powerful

effects by providing what Richard Lanham (1994) calls effective “attention

structures”, or by hitting on a useful “service” that meets

the needs of significant numbers of individuals who have a common need or interest.

For example, one might operate a blog that specializes in updating annotated

bibliographies on a particular theme or themes, or one might mobilize links

to online literature reviews, or to “cheats” for video-computer

games.

These points do not cohere well with typical approaches to pedagogy aimed at powerful writing. For example, powerful writing tends to get “individuated” in writing pedagogy. It is generally assumed that the individual is the bearer of a powerful writing capacity, and that the power in their writing is a function of his or her own understandings, as well as his or her command of the language, genre, creativity, style, and so on. As our engagement with Shirky’s ideas suggests, however, much of the power in powerful writing lies in affiliation with some larger collective.

Moreover, the three variants of power associated with Shirky’s top, middle and tail of the blogging order are not well reflected in mainstream approaches to powerful writing. So far as the top is concerned, the kind of attention-sustaining qualities manifested by stars and elites are not accounted for in pedagogical strategies like “scaffolding” effective revision and editing of written work, maintaining fluent fidelity to genre, and the like. As often as not, commanding attention is a function of breaking generic conventions, of hybridising, and so on. And in terms of power or effectiveness, in any significant sense, “revision” is icing on the cake. If there is no cake to begin with, the icing has no point. Indeed, for many of the most powerful writers, revision is something they get done for them (editors, ghost writers, etc.). Success lies in “being there” in the first place, yet this emphasis—let alone modeling how it might be achieved in substance—is notoriously absent in most writing pedagogy, with its technicist emphases on aspects of formal style, grammatical rectitude, generic purity and the like.

The same holds for the middle and the tail. In fact, most powerful writing pedagogy actually impugns the principle lying at the heart of the kind of practices Shirky identifies with the long tail of the blogging order: the wish to communicate intimately with a few pals. This is not a space where the grammatically correct sentence rules supreme, or where critical literacy is the order of the day. It is not even a space where having something significant to say holds sway. Indeed, parading one’s trivial interests and ordinariness may often be of the essence. And the idea that there is—or could possibly be—some identifiable “personal journal” weblog genre able to be reduced to a concise and definite set of criteria and norms that could be taught in classrooms as applied meta knowledge is defied by the actual forms and practices engaged by bloggers.

Similarly, while writing pedagogy often emphasises the need to attend to audience and, perhaps, to have a conception of “the ideal reader”, the fact remains that students in school-based writing classes typically have no authentic, tangible audience. Moreover, there is little or nothing in writing pedagogy that invites students to begin from their concrete membership of affinity groups, or to go about establishing a constituency for real life (non artificial) purposes. On the contrary, much of the authentic writing students do in school settings for real audiences is ultra vires and discounted, if not punished.

In these and numerous other ways there is not space to take up here, Shirky’s account of blogs and the operation of power laws provides a critical space from which to reconsider pedagogies aimed at promoting powerful writing. There is more to be said on this issue, however, which is best seen by reference to some concrete examples of blogging that were available at the time this paper was being written.

Blogs in action: applied purpose and point of view

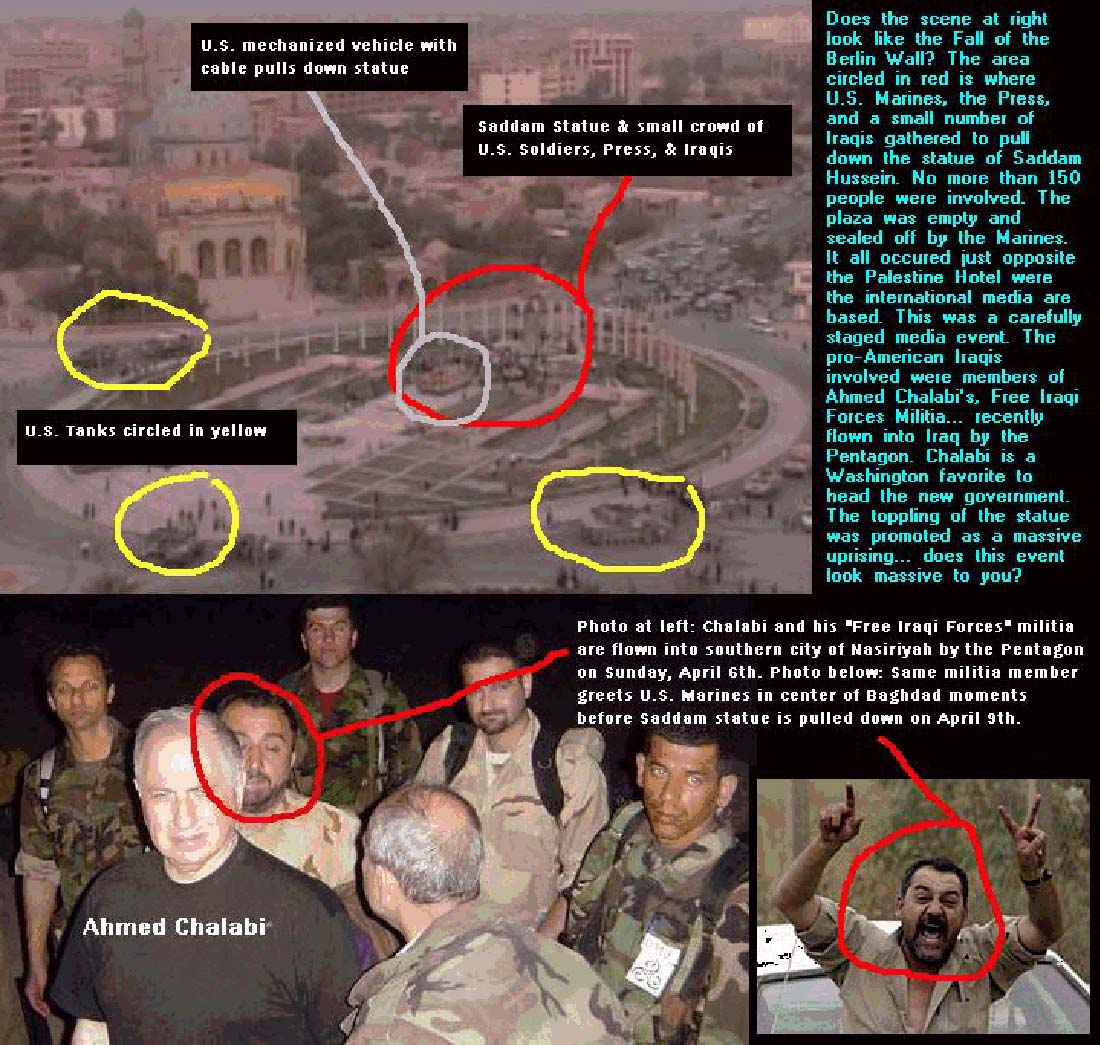

At the time of writing, mainstream media reports of the US-led invasion of

Iraq were met with impressive enactments of “point of view” on

a global scale. Broadcast media coverage by CNN (among others) of the toppling

of the statue of Saddam Hussein in el-Fardos Square, Baghdad, is a case in

point. This event was reported on television as being cheered on by large throngs

of Iraqis (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: CNN image of el-Fardos Square

Source: CNN.com (www.cnn.com/2003/WORLD/meast/04/09/sprj.irq.statue/)

However, wide-angle photographs of el-Fardos Square (where the statue was located)

taken from a Reuters website and posted on the NYC Indymedia Center weblog

(Fozzy 2003), suggest that the scenes of celebrating Iraqi crowds were carefully

staged. The photographs posted in this weblog entry show a more or less empty

square ringed by U.S. tanks, and a small crowd of no more than 150 Iraqis gathered

behind the statue as it was pulled down. A subsequent analysis of these pictures

posted on the Information Clearing House website (www.informationclearinghouse.info/article2842.htm)

pointedly drew attention to the location of the crowd in front of Hotel Palestine,

where international journalists were housed at the time. It also suggested

that members

of the crowd probably included Iraqi militia men in the employ of the U.S.

military, paid to promote the overthrow of the Hussein regime. The photo shown

below, for example, identifies a known member of the Free Iraqi Forces militia

welcoming U.S. soldiers into el-Fardos Square in Baghdad (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Analysis of el-Fardos Square photographs on the

Information Clearing House website

Source: Information Clearing House (April 10, 2003) www.informationclearinghouse.info/article2842.htm

These examples demonstrate point of view par excellence. Their authors have

a standpoint that contradicted the point of view of mainstream media like CNN.

The purpose of such blog work was to show how the “reality” of

the invasion (this choice of word, of course, rather than the official term “war”,

itself reflects our authorial point of view) can be described and understood

from the point of view of these bloggers. Other bloggers, like Andrew Sullivan,

for example, used their blogs at the same time to present a rabidly gung-ho

pro-invasion point of view. In fact, point of view is central to what blogging

is mainly about. A blog without point of view is practically a contradiction

in terms (cf., Dibbell 2000).

The same can be said with at least equal force for authorial purpose. Unless its creator has an authentic purpose—however whimsical this might be—a blog is unlikely to survive the demands on time, energy, resourcefulness, affiliation and other forms of identity work inherent in maintaining an enduring and effective blog. Aggregation services that differentiate between active and inactive or “one-time” blogs and calculate the proportions of each provide, in effect, an index on the relative availability of purpose among bloggers. Such aggregation services tend only to count as blogs those that qualify as active according to the criteria used.

While it is easy, if unfair, to take cheap shots at classroom-based writing pedagogy, the fact remains that point of view and purpose often fare badly even where a focus on promoting powerful writing is avowed. In some cases metacognitive strategies for trying to teach point of view often end up trivialising the concept, as when elementary school students are asked to rewrite a story like the Three Little Pigs from the point of view of the wolf. In other cases point of view is approached in terms of knowing how to acknowledge and honour diversity in writing. While this is important, from the standpoint of powerful writing the prior requirement is for a writer her/himself to have a point of view. This is intricately linked to identity. Achieving a strong, coherent, and reasonably consistent point of view that one can write out of (and one that may, and often does, change over time as the wrier comes to know more about a topic, issue, practice, etc.), and write out of powerfully, is not a matter of technique, or of metacognitive awareness. It is about being somebody who represents a standpoint that one takes sufficiently seriously to be able to write out of with conviction. These points hold strongly for much work that has been undertaken in classrooms in the name of critical literacy as a species of powerful literacy.

The centrality of a strong and authentic sense of purpose may well explain the highly visible and active interest within blogging communities in the quality of blogs. The “Bloggies” are an example of this concern for quality. These are annual awards established by Nikolai Nolan (www.fairvue.com/?feature=awards2003) to give due recognition to outstanding weblogs and elements of weblogs. Mirroring parallel awards in established media, key categories within the Bloggies include: “Best meme”, “Best topical weblog”, “Best article or essay about weblogs”, and “Best tagline for a weblog”.

This will to quality is reinforced from the other side as well – by “honoring” what good blogs are not. An annual “Anti-Blog” award ceremony that “roast[s] bloggers for being boring or lame or obsessed or weird” (Manjoo 2002: 2) has been established, and in 2003 Anti-Bloggies (www.antibloggies.com) were awarded in 30 categories. These ranged from “Most distracting background image”, to “Most banal content”, through to “Worst attempt at a meme”. From the perspective of self-appointed peer reviewers of quality, the cardinal blogging sin probably is to be boring. In particular, the Anti-Bloggies come down hard on the “cheese sandwich effect” – where blogs have nothing to say beyond describing what their writers had for lunch that day.

Advice to novice bloggers usually emphasises the need for good quality, accessible writing. “Readers [of weblogs] come from a variety of backgrounds. Write to the point, be simple and short. … Usually I spend a minute or two on a weblog to see if there is anything new and interesting. You probably have 30 to 45 seconds to get a user’s attention” (Shanmugasundaram 2002: 143). Matters of design and style—seen by the bloggerati as tightly interwoven—are also emphasised. Having a consistent style in terms of font type, text layout and the like “helps in [drawing] readers’ attention to a specific area” and having “a unique style of writing helps in getting regular readers” (ibid.). For example, the publisher of Metascene emphasizes the importance of developing a style. This particular blogger identifies his or her own writing style as “corny and pretentious; a profound arrogance hiding behind a fig leaf of false modesty; spineless; half-smart” (Metascene 2002: 152).

Whatever we might thing of such priorities and the values and attitudes that may be associated with them, it is evident that so far as matters of purpose and a concern for quality are concerned the “orders” evident in the blogging world and the world of classroom writing pedagogy are almost neatly reversed. Bloggers begin from a felt sense of purpose and take it from there, or else simply stop blogging. Writing pedagogy usually does not presume purpose, but somehow hopes to prepare learners for being effective writers in contexts where they do encounter serious purpose. Likewise, bloggers begin with a point of view they want to share with others. Without this there is no cogent basis from which to blog. By contrast, so much powerful writing pedagogy actually sets out from the assumption that student points of view need to be developed, shaped up, or made more worthy of attention.

Blogs at school

Given the ease with which blogs can be established it is quite possible that

they could become the new turn of the wheel of technology integration in schools—following

on from the embrace of school and teacher websites and PowerPoint presentation

assignments in every subject area. The school blogs we have located to date

on the popular Schoolblogs.com hosting service provide little evidence of students

and teachers working from a base of authentic purposefulness. Many student

posts to school-endorsed blogs look like being compulsory requirements and

linked to student grades for the course. The lively humour and wit of blogger

posts elsewhere and the written comments they often attract from readers are

missing—few school blogs even have the “comments” function

enabled. The quality of writing posted to school blogs varies from the “why

bother” to lists of items pertaining to a subject area topic or theme

being studied in class, through to essayist texts. There is little evidence

of idea development. High proportions of student postings exemplify the “cheese

sandwich effect.” Evidence of well defined and strongly held points of

view are equally conspicuous by their absence.

In one example a teacher at an English language school in the Netherlands incorporated

student use of class and personal weblogs into his teaching. The Tudor Exploration

project, for example, requires students to post assignment work to the class

blog (class6f.bsablogs.com/Class6F). Typical posts included:

Some students in this same class have created personal weblogs, but these are uniformly underdeveloped and none of them indicates any evidence of significant personal investment. In one posting a student states that she is updating her blog from New York. She says nothing about New York or her trip, simply that the present update comes from New York. Other students appear to have confused weblogs with instant messaging. For example:

“Where is everybody? Hi, everyone.. have got my guitar lesson in 20 minutes. Crazyland isn’t so crazy anymore and furthermore.. the login button has gone!! So I cannot access it from anywhere except my home. Glad you got those grades Cliff J. Bye.”

Another student posts:

“helloooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo i just dropped in to say a gigantic enormous hellooooooooooo. Good bye to you and you and you.”

In a second example from a different context a 7th grade science teacher

uses his blog to post assignment descriptions and assessment criteria and

related

websites (e.g., “You will create an essay on Evolution and explain why

it was and still is such a controversial theory”), to link to Quicktime

videos of science quiz contests, to post an advance notice of a forthcoming

slide show documenting the school‘s participation in the Martin Luther

King March for peace and justice, textbook ordering information, and so

on. Each posting is linked to a comments section, but no comments had been

posted

when we visited the blog. There is no evidence of student participation

in this blog, although students (and perhaps parents) are clearly the target

readers.

It is not our intention here to make school blogs an easy target. Rather, our concern is that school blogs typically present themselves as earnest attempts to meld new technology use, student interest and school work in ways that risk “killing” the medium by reducing its potential scope and vitality to menial school tasks in which students seemingly lack any genuine purpose.

Larger possibilities

In relation to using new technologies effectively for informational purposes, Chris Bigum (2002: 136) argues that what ultimately matters “is expertise, point of view, a place to stand from which to make sense of information.” So far as formal learning contexts are concerned, this will at the very least involve learners and teachers beginning from having authentic problems and questions to investigate (Beach and Bruce 2002). From such a starting point they will better be able to see the links between effective research strategies, social events and phenomena, and the process of becoming knowledgeable about something (cf., Lankshear and Snyder 2000).

When Google bought Blogger in early 2003 some technorati speculated on the significance and smartness of this manouever. Matt Webb (2003) and Steve Johnson (2003) observed that search engines have become extremely efficient as means for obtaining information. They argued, however, that other than the blog there is no efficient digital tool for archiving and tracking information in ways that can narrate paths taken in the systematic exploration and development of a theme, topic or point of view and thereby reveal a structure of knowledge. Blogging lends itself to this kind of memory extension work in ways that produce useful audit trails of ideas that emerge and develop as one searches the internet for information on matters of personal interest. A blog, in other words, can serve as a kind of “back up brain”.

Johnson argues that the acquisition of Blogger—perhaps the premier free blog hosting service available online—means that “[i]nstead of just helping you find new things, Google could help you keep track of what you’ve already found” by managing users’ “surfing histories” (2003: 1). This augmentation of human memory recalls Vannevar Bush’s conception of the “memex” in the mid 1940s (Bush 1945). Bush’s memex machine comprised a desktop with inlaid screens and levers from which the user could access, among other things, the entire Encyclopedia Britannica, complete books, personal documents, and the like. According to Bush (1945: 1),

A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his [or her] memory.

The memex resembles the modern computer—with one important difference.

Bush emphasized the importance of being able to annotate texts accessed via

the memex, which would effectively constitute a record of the path the user

had taken through the information space and that these records or “trails” would

be useful in “amplifying the signal of human memory” (Johnson

2003: 1).

Johnson suggests how Google’s acquisition of Blogger could actualise

the vision of the memex. It could mean that in the near future every time one

conducts a search, each link clicked on is automatically “blogged” (that

is, entered into a weblog and date stamped), “storing for posterity the

text and location of the document” (ibid: 2). Users could choose whether

to make these blogged entries public and available for comment or not. Johnson

also envisages Google generating a list of pages that link to the pages in

one’s blogged archive—making a useful, searchable subset of the

internet that has been tailored specifically to meet the user’s interests

and information needs or wants.

Matt Webb (2003) describes the Google-Blogger process in terms of Google documenting what users see and what users do when searching via their service. In Webb’s conception of the Google memex, Google searches would return information on information trails that were “well worn” or usefully uncommon, or would distinguish between trails people suggested and trails people actually followed when searching a similar or related topic, and so on.

Given such ideas about the epistemic potential of blogs, it is not difficult to imagine how blogging could become a potent dimension of school-based learning. This would require getting beyond the kinds of “pretend” research activities (classroom “projects”) that typically prevail in school curriculum work, and beginning from significant problems that call for serious data collection and analysis. In such contexts blogging could be made into a highly sophisticated form of learning that engages directly with systematicity in searching. This would include being able to differentiate among types of data—such as well-used, quirky but useful, outdated, misleading, etc. Blogging as learning/Learning as blogging could also become an integral component of processes of developing point of view in relation to new topics, events and issues, of auditing this development in ways that are visible to the user and relevant others, and of generally pursuing meaningful purposes characteristic of expert-like research.

In this kind of vein, Torill Mortensen and Jill Walker (2002) are currently documenting the development and use of blogs as research tools. Mortenson and Walker both conduct much of their own research online, and each began a weblog as a way of reminding themselves what their study focus was at the time. These weblogs, however, soon “developed beyond digital ethnographer’s journals into a hybrid between journal, academic publishing, storage space for links and site for academic discourse” (p. 250). Thus, blogs may well become important indices to and evidence of personal and collective knowledge structures by both recording and unveiling an individual’s or a group’s knowledge or epistemic effort over time.

Consequently, if school weblogs were approached from the standpoint of providing potential audit trails of knowledge built up over a period of time, they could contribute powerfully to promoting knowledge production, as well as enabling reflection upon and evaluation of how this knowledge was arrived at. A blog that records links, commentaries, and informed analysis, and that is open to being read by and commented upon by interested others, can become an objective artifact of collegial activity: one that is mediated by experts and learners in mutually beneficial ways. Blogs have much potential for promoting reflection on one’s knowledge trails across the internet. Understanding where one went in an online search and why one went there thus becomes a key component of a blog, in ways that are not so evident and are not necessarily available in 5-part essay writing. Interested others could suggest to the blogger alternative trails or routes through a knowledge structure built around an interest in a particular topic, field or issue. This kind of engagement defaults to encouraging the blogger to regularly update and evaluate his or her point of view on a topic or issue when feedback or comments from others challenge the blogger to produce persuasive arguments, crisp analyses, and so on. At the same time, these interested others could also feed alternative angles and perspectives into the mix that can then be followed up on by the blogger.

In these and other ways research as blogging, and blogging as research, could potentially become potent pedagogical approaches to writing. And such writing might indeed be appropriately described as powerful.

References

Blood, R. (2002a). Introduction. In Editors of Perseus Publishing (Eds.). We’ve Got Blog: How Weblogs are Changing Culture. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. ix-xiii.

Blood, R. (2002b). Weblogs: A history and perspective. In Editors of Perseus Publishing (Eds.). We’ve Got Blog: How Weblogs are Changing Culture. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. 7-16.

Bush, V. (1945). As we may think. Atlantic Monthly. July. www.theatlantic.com/unbound/flashbks/computer/bushf.htm (accessed 19 April, 2003).

Christie, F. (1987) Genres as choice. In I. Reid (ed), The Place of Genre in Learning: Current Debates. Typereader Publications No.1. Geelong: Deakin University, Centre for Studies in Literacy Education. 22-34.

Dibbell, J. (2000). Portrait of the blogger as a young man. In Editors of Perseus Publishing (Ed.). We’ve Got Blog: How Weblogs are Changing Culture. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. 69-77.

Fozzy (2003). A tale of two photos. NYC Indymedia Center. nyc.indymedia.org/front.php3?article_id=55268&group=webcast. April 9. (accessed 15 April, 2003).

Goldhaber, M. (1997) The attention economy and the net. First Monday. www.firstmonday.dk/issues/issue2_4/goldhaber/index.html (accessed 2 Jul. 2000).

Goldhaber, M. (1998) The attention economy will change everything, Telepolis (Archive 1998). www.heise.de/tp/english/inhalt/te/1419/1.html (accessed 30 Jul. 2000).

Johnson, S. (2003). Google’s memory upgrade. Slate. 6 March. slate.msn.com/id/2079747 (accessed 19 April 2003).

Manjoo, F. (2002). Blah, blah, blah and blog. Wired.com. 18 February.www.wired.com/news/culture/0,1284,50443,00.html (accessed 19 April 2003).

Martin, J. (1993) Genre and literacy: modeling context in educational linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 13: 141-72.

Martin, J. and Rothery, J. (1993). Grammar: Making meaning in writing, in B. Cope and M. Kalantzis (eds.) The Powers of Literacy: A Genre Approach to Teaching Writing. London: Falmer, 137-53.

Metascene (2002). Ten tips for building a bionic weblog. In Editors of Perseus

Publishing (Ed.). We’ve Got Blog: How Weblogs are Changing Culture. Cambridge,

MA: Perseus Publishing. 150-156.

Mortenson, T. and Walker, J. (2002). Blogging thoughts: Personal publication

as an online research tool. In A. Morrison (Ed.), Researching ICTs in Context.

Oslo: Intermedia Report. 249-279.

Shanmugasundaram, K. (2002). Weblogging: Lessons learned. In Editors of Perseus Publishing (Ed.). We’ve Got Blog: How Weblogs are Changing Culture. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing. 142-144.

Webb, M. (2003). Google buy Pyra 2. interconnect.org. February. interconnected.org/notes/2003/02/Google_buy_Pyra_2.txt (accessed 19 April 2003).

back to aera symposia index / back to work index / back to main index