![]()

Result(s): Confederate victory

Other Names: Marye's Heights

Location: Spotsylvania County and Fredericksburg

Campaign: Fredericksburg Campaign (November-December 1862)

Date(s): December 11-15, 1862

Principal Commanders: Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside [US]; Gen. Robert E. Lee [CS]

Forces Engaged: 172,504 total (US 100,007; CS 72,497)

Estimated Casualties: 17,929 total (US 13,353; CS 4,576)

Source:

![]()

Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan read the orders he had just received from Washington with careful composure. Looking up slowly, he spoke without revealing his bitter disappointment: "Well Burnside, I turn the command over to you." With these words, the charismatic, overcautious leader of the Union's most famous fighting force exited the military stage, yielding to a new man with a different vision of the war.

When Maj. Gen.Ambrose E. Burnside inherited the Army of the Potomac on November 7, 1862, its 120,000 men occupied camps near Warrenton, Virginia. Within two days, the 38-year-old Indiana native proposed abandoning McClellan's sluggish southwesterly advance in favor of a 40-mile dash across country to Fredericksburg. Such a maneuver would position the Federal army on the direct road to Richmond, the Confederate capital, as well as secure a safe supply line to Washington.

President Lincoln approved Burnside's initiative but advised him to march quickly. Burnside took the President at his word and launched his army toward Fredericksburg on November 15. The bewhiskered commander (whose facial hair inspired the term "sideburns") also altered the army's organization by partitioning it into thirds that he styled "grand divisions." The blueclad veterans covered the miles at a brisk pace, and on November 17 the lead units arrived opposite Fredericksburg on Stafford Heights.

Burnside's swift march placed Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia at a perilous disadvantage. Lee had boldly divided his 78,000 men, leaving part of them with Lt. Gen. Thomas J. ("Stonewall") Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley while sending the rest with Lt. Gen. James Longstreet to face the Federals directly. Lee had not anticipated Burnside's shift to Fredericksburg and now neither wing was in position to defend the old city.

The Federals could not move south, however, without first crossing the Rappahannock River, the largest of several river barriers that flowed astride their path to Richmond. Because the civilian bridges had been destroyed earlier in the war, Burnside sent for pontoon equipment. A combination of miscommunication, inefficient army bureaucracy, and poor weather delayed the arrival of the floating bridges, and when they finally arrived on November 25, so had the Army of Northern Virginia.

Burnside's strategy depended upon an unopposed crossing of the Rappahannock. Consequently, his plan had foundered before a gun had been fired. Nevertheless, the country demanded action. Winter weather would soon render Virginia's highways impassable and end serious campaigning until spring. The Union commander had no choice but to search for a new way to outwit Lee and satisfy the public's desire for victory.

When Longstreet's corps appeared at Fredericksburg on November 19, Lee ordered it to occupy a range of hills behind the town, extending from the Rappahannock on its left to marshy Massaponax Creek on its right. When Jackson's men arrived more than two weeks later, Lee dispatched them as far as 20 miles downriver. The Confederate army thus guarded a long stretch of the Rappahannock, unsure of where the Federals might attempt a crossing.

Burnside harbored the same uncertainties. After an agonizing deliberation, he finally decided to build bridges at two places opposite the city and near the mouth of Deep Run, a mile downstream. The Union commander knew that Jackson's corps could not assist Longstreet in opposing a river passage near town. Thus Burnside's superior forces would encounter only half of Lee's soldiers. Once across the river, the Federals would strike Longstreet's overmatched defenders, outflank Jackson, and send the whole Confederate army reeling toward Richmond.

Burnside's lieutenants doubted the practicality of their chiefs plan. "There were not two opinions among the subordinate officers as to the rashness of the undertaking," wrote one corps commander. Nevertheless, in the foggy pre-dawn hours of December 11, Union engineers crept to the riverbank and began laying the pontoons. Skilled workmen of the 50th New York Engineer Regiment had pushed the upstream spans more than halfway to the right bank when the sharp crack of musketry erupted from the riverfront houses and yards of Fredericksburg.

These shots came from a brigade of Mississippians under Brig. Gen. William Barksdale, whose job was to delay any Federal attempt to cross the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg. "Nine distinct and desperate attempts were made to complete the bridge[s]," reported a Confederate officer, "but every one was attended by such heavy loss from our fire that the efforts were abandoned...."

Burnside now turned to his artillery chief, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, and ordered him to blast Fredericksburg into submission with some 150 guns trained on the city from Stafford Heights. Such a barrage would surely dislodge the Confederate infantry and permit completion of the bridges. Shortly after noon, Hunt gave the signal to commence fire. "Rapidly the huge guns vomited forth their terrible shot and shell into every corner and thoroughfare" of Fredericksburg, remembered an eyewitness.

The bombardment continued for nearly two hours, during which time 8,000 projectiles rained destruction on Fredericksburg. Then the grand cannonade ceased, the Federal gunners confident their barrage had silenced Confederate opposition. Once again the engineers ventured warily to the ends of their unfinished bridges. Suddenly—impossibly—muzzles flashed again from the rubble-strewn streets and more pontoniers tumbled into the cold waters of the Rappahannock.

Burnside now authorized volunteers to ferry themselves across the river in the clumsy pontoon boats and drive the Confederates out. Men from Michigan, Massachusetts, and New York scrambled aboard the scows, frantically pulling at oars to navigate the hazardous 400 feet to the opposite side. Once on shore, the Federals charged Barksdale's marksmen who, despite orders to fall back, fiercely contested each block in a rare exampie of street fighting during the Civil War. After dusk the brave Mississippians finally withdrew to their main line, the bridge-builders completed their work, and the Army of the Potomac entered Fredericksburg.

December 12 dawned cold and foggy. Bumside began pouring reinforcements into the city but made no effort to organize an attack. Instead, the Northerners squandered the day looting and vandalizing homes and shops. A Connecticut chaplain remembered seeing soldiers "break down the doors to rooms of fine houses, enter, shatter the looking-glasses with the blow of the ax, [and] knock the vases and lamps off the mantel- piece with a careless swing.... A cavalry man sat down at a fine rosewood piano.. .[and] drove his saber through the polished keys, then knocked off the top [and] tore out the strings...."

Lee, on the other hand, utilized the time by recalling half of Jackson's corps from its isolated posts downstream. Following a personal reconnaissance during the afternoon, Stonewall sent word to the rest of his troops to march that night to the point of danger closer to the city. Forced by political considerations to bring on a battle, Burnside's own needless delay on December 12 lengthened the odds against a favorable outcome once the fighting started.

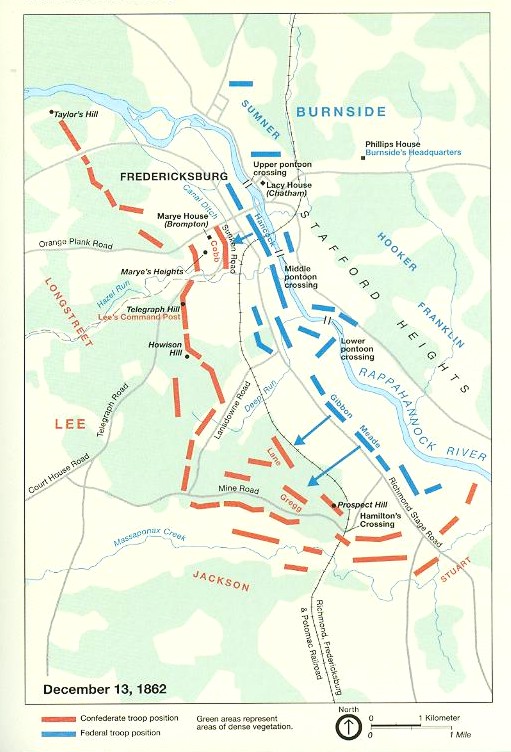

The Battle of Fredericksburg unfolded in a natural amphitheater bounded on the east by the Rappahannock River and on the west by a line of hills fortified by Lee. When Jackson's men arrived from downstream, Longstreet sidled his corps to the north, defending roughly five miles of Lee's front. He mounted guns at strong points such as Taylor's Hill, Marye's Heights, Howison Hill, and Telegraph (later Lee) Hill, the Confederate command post. Longstreet's five divisions of infantry supported his artillery at the base of the slopes.

The Battle of Fredericksburg unfolded in a natural amphitheater bounded on the east by the Rappahannock River and on the west by a line of hills fortified by Lee. When Jackson's men arrived from downstream, Longstreet sidled his corps to the north, defending roughly five miles of Lee's front. He mounted guns at strong points such as Taylor's Hill, Marye's Heights, Howison Hill, and Telegraph (later Lee) Hill, the Confederate command post. Longstreet's five divisions of infantry supported his artillery at the base of the slopes.

Below Marye's Heights a Georgia brigade under Brig. Gen. Thomas R. R. Cobb stood along a 600-yard portion of the Telegraph Road, the main thoroughfare to Richmond. The road had been cut into the hillside, giving it a sunken appearance. Stone retaining walls paralleling the shoulders transformed this peaceful stretch of country wagon road into a ready-made trench.

Jackson's end of the line possessed less inherent strength. His command post at Prospect Hill rose only 65 feet above the surrounding plain. He compensated for the weak terrain by stacking his four divisions one behind the other to a depth of nearly a mile. Any Union offensive against Lee's seven-mile line would, by necessity, have to cross an exposed stretch of land in the teeth of a deadly artillery crossfire before reaching the Confederate infantry.

Burnside issued his attack orders early on the morning of December 13. They called for an assault against Jackson's corps by Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin's Left Grand Division, to be followed by an advance against Marye's Heights by Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner's Right Grand Division. The army commander used tentative, ambiguous language in his directives, reflecting either a lack of confidence in his plan or a misunderstanding of his opponent's posture—perhaps both.

Burnside had reinforced Franklin's sector that morning to a strength of some 60,000 men. Franklin, a brilliant engineer but cautious combatant, placed the most literal and conservative interpretation on Burnside's ill-phrased instructions. He designated Maj. Gen. George G. Meade's division—just 3,800 troops—to spearhead his attack.

Meade's men, Pennsylvanians all, moved out in the misty half-light about 8:30 a.m. and headed straight for Jackson's line, not quite one mile distant. Suddenly, artillery fire exploded to the left and rear of Meade's lines. Maj. John Pelham had valiantly moved two small guns into position along the Richmond Stage Road perpendicular to Meade's axis of march. The 24-yearold Alabamian ignored orders from Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown ("Jeb") Stuart to disengage and continued to disrupt the Federal formations for almost an hour. General Lee, watching the action from Telegraph Hill, remarked, "It is glorious to see such courage in one so young."

When Peiham exhausted his ammunition and withdrew, Meade resumed his approach. Jackson patiently allowed the Federals to close to within 500 yards of the wooded elevation where a 14-gun battery lay hidden in the trees. As the Pennsylvanians drew near to the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad north of Hamilton's Crossing, Stonewall's concealed artillery ripped gaping holes in Meade's ranks. The beleaguered Federals sought protection behind wrinkles of ground in the open fields.

Union guns responded to Jackson's cannoneers A full-scale artillery duel raged for an hour, killing so many draft animals that the Southerners called their position "dead horse hill." When one Union shot spectacularly exploded a Confederate ammunition wagon, the crouching Federal infantry let loose a spontaneous Yankee cheer. Meade, seizing the moment, ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge.

Meade's soldiers focused on a triangular point of woods that jutted toward them across the railroad as the point of reference for their assault. When they reached these trees they learned, to their delight, that no Southerners defended them. In fact, Jackson had allowed a 600-yard gap to exist along his front and Meade's troops had accidentally discovered it.

The Federals pushed through the boggy forest and hit a brigade of South Carolinians who at first mistook them for retreating Confederates. Their commander, Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg, paid for this error when a fatal bullet hit his spine. Meade's men rolled forward and gained the crest of the heights deep within Jackson's defenses.

The Federals pushed through the boggy forest and hit a brigade of South Carolinians who at first mistook them for retreating Confederates. Their commander, Brig. Gen. Maxcy Gregg, paid for this error when a fatal bullet hit his spine. Meade's men rolled forward and gained the crest of the heights deep within Jackson's defenses.

Jackson, who had learned of the crisis in his front from one of Gregg's officers, calmly directed his vast reserves to move forward and restore the line. The Southerners raised the "Rebel Yell" and slammed into the exhausted and outnumbered Pennsylvanians. "The action was close-handed and men fell like leaves in autumn," remembered one Federal. "It seems miraculous that any of us escaped at all."

Jackson's counterattack drove Meade out of the forest, across the railroad, and through the fields to the Richmond Stage Road. Union artillery eventually arrested the Confederate momentum. A Federal probe along the Lansdowne Road in the late afternoon and an aborted Confederate offensive at dusk ended the fighting on the south end of the field.

Burnside waited anxiously at his headquarters in the Phillips house on Stafford Heights for news of Franklin's offensive. According to the Union plan, the advance through Fredericksburg toward Marye's Heights would not commence until the Left Grand Division began rolling up Jackson's corps. By late morning, however, the despairing Federal commander discarded his uncertain strategy and ordered Sumner's grand division to attack.

In several ways, Marye's Heights offered the Federals their most promising target. Not only did this sector of Lee's defenses lie closest to the shelter of Fredericksburg, but the ground rose less steeply here than on the surrounding hills. Nevertheless, Union soldiers had to leave the city, descend into a valley bisected by a water-filled canal ditch, and ascend an open slope of 400 yards to reach the base of the heights. Artillery atop Marye's Heights and nearby elevations would thoroughly blanket the Federal approach. "A chicken could not live on that field when we open on it," one Confederate cannoneer boasted.

Sumner's first assault began at noon and set the pattern for a ghastly series of attacks that continued, one after another, until dark. As soon as the Northerners marched out of Fredericksburg, Longstreet's artillery wreaked havoc on the crisp blue formations. The Federals then encountered a deadly bottleneck at the canal ditch, which was spanned by partially destroyed bridges at only three places. Once across this obstacle, the attackers established shallow battle lines under cover of a slight bluff that shielded them from Confederate eyes.

Orders then rang out for the final advance. The ground beyond the canal ditch contained a few buildings and fences, but from a military perspective it provided virtually no protection. Dozens of Confederate cannon immediately reopened on the easy targets and when the Federals had traversed about half the remaining distance, a line of rifle fire erupted from the Sunken Road, decimating the Northerners. Survivors found refuge behind a small swale in the ground or retreated back to the canal ditch valley.

Quickly a new Federal brigade burst toward Marye's Heights and the "terrible stone wall," then another, and another, until three entire divisions had hurled themselves at the Confederate position. In one hour, the Army of the Potomac lost nearly 4,000 men; but the madness continued.

Although General Cobb suffered a mortal wound early in the action, the Southern line remained firm. A South Carolina brigade joined North Carolinians in reinforcing Cobb's men in the Sunken Road. Confederate infantry stood four ranks deep, maintaining a ceaseless musketry while gray-clad artillerists fired over their heads.

Still the Union units kept on coming. "We came forward as though breasting a storm of rain and sleet, our faces and bodies being only half-turned to the storm, our shoulders shrugged," remembered one Federal. "Everybody from the smallest drummer boy on up seemed to be shouting to the full extent of his capacity," recalled another. But each blue wave crested short of the goal. Not a single Union soldier laid his hand on the stone wall.

Lee, from his lofty perch on Telegraph Hill, watched Longstreet's almost casual destruction of Burnside's divisions as Jackson's counterattack repulsed Meade. Turning toward Longstreet, the Confederate commander remarked soberly, "It is well that war is so terrible. We should grow too fond of it."

Burnside ordered Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker's Center Grand Division to join the attack in the afternoon. Late in the day, troops from the Fifth Corps moved forward. Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys led his division through the human debris of the previous assaults. Some of Humphreys's soldiers shook off wellmeaning hands that clutched at them to prevent their advance. Part of one brigade sustained its momentum until it drew within 25 yards of the stone wall. There it, too, melted away.

The final Union effort began after sunset. Col. Rush C. Hawkins's brigade, the fifteenth Federal brigade to charge the Sunken Road that day, enjoyed no more success than its predecessors. Darkness shrouded the battlefield and at last the guns fell silent.

The final Union effort began after sunset. Col. Rush C. Hawkins's brigade, the fifteenth Federal brigade to charge the Sunken Road that day, enjoyed no more success than its predecessors. Darkness shrouded the battlefield and at last the guns fell silent.

The hideous cries of the wounded, "weird, unearthly, terrible to hear and bear," echoed through the night. Burnside planned to renew the assaults on December 14, but his subordinates talked him out of this suicidal scheme. During the night of December 15-16, Burnside skillfully withdrew his army to Stafford Heights, dismantling his bridges behind him. Thus the Fredericksburg Campaign ended.

==================

SUMMARY

==================

Grim arithmetic tells only a part of the Fredericksburg story. Lee suffered 5,300 casualties but inflicted more than twice that many losses on his opponent. Of the 12,600 Federal soldiers killed, wounded, or missing, almost two-thirds fell in front of the stone wall.

Despite winning in the most overwhelming tactical sense, however, the Battle of Fredericksburg proved to be a hollow victory for the Confederates. The limitless resources of the North soon replaced Burnside's losses in manpower and materiel. Lee, on the other hand, found it difficult to replenish either missing soldiers or needed supplies. The Battle of Fredericksburg, although profoundly discouraging to Union soldiers and the Northern populace, made no decisive impact on the war. Instead, it merely postponed the next "On to Richmond" campaign until the spring.

Source:

Last Updated 10 May 2002

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times

Click on any [Item] below to go to that page

[Return to Glossary Page]

[Return to 43rd Pennsylvania Home Page]

© 1998-2004 Benjamin M. Givens, Jr.

![]()