"It is a well-known fact that the peoples of Germany never live in cities and will not even have their houses adjoin one another. They dwell apart, dotted about here and there, wherever a spring, plain, or grove takes their fancy.

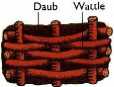

"It is a well-known fact that the peoples of Germany never live in cities and will not even have their houses adjoin one another. They dwell apart, dotted about here and there, wherever a spring, plain, or grove takes their fancy. During the early Middle Ages wood was still the most popular building material in northwestern Europe; the city of York in England was founded by Viking settlers as "Jorvik", and excavations there showed that most of the houses were built with timber and the daub-and-wattle technique.

During the early Middle Ages wood was still the most popular building material in northwestern Europe; the city of York in England was founded by Viking settlers as "Jorvik", and excavations there showed that most of the houses were built with timber and the daub-and-wattle technique. Interior:

Interior: The Scandinavian houses found in York had beds against the walls made of raised earth and wooden planks, which could also be used to sit on; richer houses also had tables, chairs, and benches, decorative tapestries on the walls and sometimes a decorated door and door posts.

The Scandinavian houses found in York had beds against the walls made of raised earth and wooden planks, which could also be used to sit on; richer houses also had tables, chairs, and benches, decorative tapestries on the walls and sometimes a decorated door and door posts. The "owlsboard":

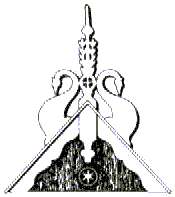

The "owlsboard": Housefront signs were used in many countries, I have already described the owlsboard but there were many more types that can be found scattered over northern Europe, the custom of placing frontsigns on houses has continued for many centuries and is still used today in many countries; many old heathen symbols are still used in most of the modern signs though they are often combined with Christian symbols.

Housefront signs were used in many countries, I have already described the owlsboard but there were many more types that can be found scattered over northern Europe, the custom of placing frontsigns on houses has continued for many centuries and is still used today in many countries; many old heathen symbols are still used in most of the modern signs though they are often combined with Christian symbols.

|

|

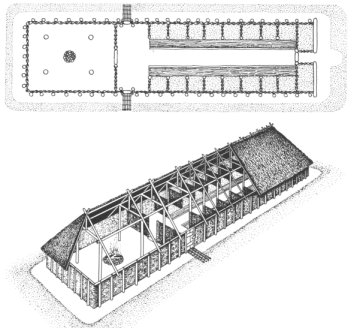

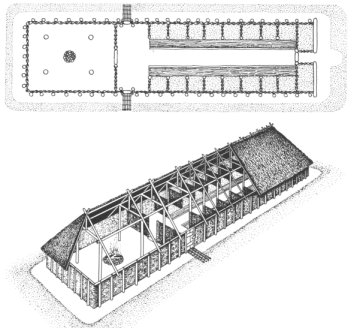

| Reconstruction of a Germanic farm found in the Netherlands; notice the "Landweer" defence around it (see: fortresses). | Ground plan of a typical Germanic house. |

|

|

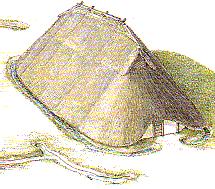

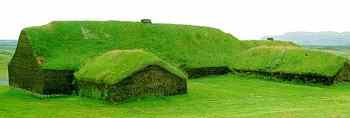

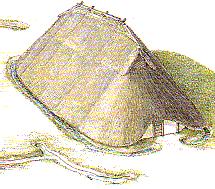

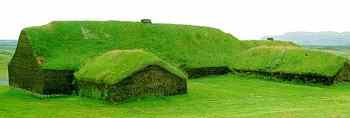

| Reconstruction of a West Frisian farm from the Bronze Age that was found in the Netherlands, although this is a Pre-Germanic house from 1600BC you can clearly see the similarities with later Germanic houses. | Reconstruction of a 12th century turf house at Stöng in Iceland. |

|

|

| Reconstruction of a Norse longhouse that was found at Fyrkat in Denmark. | Reconstruction of a Norse longhouse that was found at Trelleborg in Denmark. |

|

|

| A Saxon style "Lös hoes" farm, this type is still very common in the Dutch provinces Twente and Gelderland. | Modern Saxon "Hallehuus" farm in Uddel, the Netherlands, notice the wolfsends. |