Both Walpurgis and May Day are not genuine Germanic holidays; they are a later attempt to Christianize the old heathen Spring celebrations by connecting them to a saint and holding them on the date of her canonization.

Midsummer:

Midsummer:This holiday was held on the day of the Summer Solstice (the longest day of the year), the date of the Summer Solstice varies but it mostly takes place on June the 21st.

Midsummer was mainly dedicated to the Alfen but gods like Thunar and Frey may have also played an important role.

There are reasons to believe that Balder (the god of light) was also worshipped on Midsummer, in the Catholic parts of the Netherlands the holiday of the saint of light (lichtheilige) st.-John (st.-Jan) is celebrated on June 24, which coinsides with Midsummer.

On this day some people still burn incense for st.-Jan, which is called wierook ("hallowing smoke") in Dutch, to become a good harvest.

In the city of Huissen a bonfire called st.-Jansvuur ("st.-John's fire") is lit every year, which also includes someone dressed up as a wildman.

Many places also still have a sint-Jansberg ("st.-John's hill") that may have been used for the Midsummer celebration in ancient times.

Some of the customs during Midsummer were lighting Bonfires on fields near the village and holding dances, the people also jumped over bonfires for good luck and health during the upcoming year and it is believed that the original meaning of lighting bonfires was to raise the sunheat for a warmer summer.

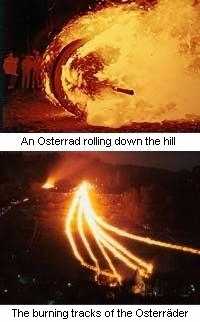

Another important tradition during the solstice was rolling burning sunwheels down hills; in the days before Midsummer the people had made weels filled with straw that were set on fire in the evening and rolled down a hill, which created multiple burning tracks from the top of the hill to the foot, which may have symbolized the orbit of the sun and fertilized the Earth

This custom was performed in England, western Europe, and central Europe until the 19th century, I have also heard about this custom being performed in Scandinavia but I have no details about that.

These days a Christianized version of this custom still survives in Germany where the burning wheels are called "Osterräder" (Easter-wheels), especially in the city of Lügden this custom is popular and many people from around the area still come to watch it.

More information about the Easter Wheels can be found at http://www.osterraederlauf.com.

Harbista (*Harbistaz = Autumn):

Harbista (German: Herbst, Dutch: Herfst, Icelandic: Haust, Danish/Norwegian: Hřst, Swedish: Höst) was celebrated on the full moon around the autumn equinox, which takes place around September 21.

Harbista was dedicated to the end of the harvest period and a preparation of the sowing of the winter grain, it is believed that especially the Alfen spirits and the fertility gods of the Wanen family played an important role in this celebration.

In his Annales (book I, 50-51) the writer Tacitus mentions that the Romans attacked the Germanic tribe of the Marsii during their autumn celebration and that they were too drunk to defend themselves because of this, he also mentions that the celebration was "a night of festivity, with games, and one of their grand banquets".

At the end of the harvest it was also customary that the farmers left some of the harvest behind on the field as an offering to the spirits and the gods to show their gratitude.

In Scandinavia Harbista was also called Alfablót, which points to the important role that the Alfen may have played in this celebration, the most important aspect of Harbista was probably thanking the Alfen en fertility gods for the harvest by offering to them.

Winternights:

Winternights:Held from October the 14th to October the 17th, this holiday mostly lasted for 3 days and was held to ask for a good year and a good (mild) winter, in the beginning of the celebration, which was the evening of October the 13th (the day began on the evening before) there was a feast with much drinking in which the Landwights (nature spirits) and the Disen (female guardian spirits) were honoured.

In Scandinavia a special "Dísablót" was also held during one of the 3 days of Winternights to honour the Disen (or Dísir in Old Norse), it seems that women played a leading role in the offerings that were made to the Disen.

Mothernight:

This holiday was celebrated on the evening before Yule started (mostly the evening of December 20).

During Mothernight (Old Norse: Modraniht) nightly sacrifices were made to the "mothers", the word "mother" referred to female ancestors in this context.

Midwinter/Yule (*Jegwla = The Yelling):

Midwinter, also known as Yule (Anglo-Saxon), Jól (Old Norse), Jul (Scandinavian and German), Joel (Dutch), or Twelve Nights, was held at the Winter Solstice.

The word Yule means "to yell" or "to cheer" (German "johlen" and Dutch "joelen"), which may refer to the merry drinking feasts that were held during this period though a more plausible explanation is that it refers to the noise that the people made to scare off evil spirits during this time, just like the Chinese light firecrackers to scare off the evil spirits.

Jól was the most important holiday of the year and a combination of a fertility festival and a commemoration for the dead; this combination sounds weird but since Jól was the Germanic new year it represented both the "death" of old and the "birth" of new, it started on the day of the Winter solstice, which was mostly December the 21st, this day was also called "Midwinter" and was opened with merry celebrations, in Frisian and Saxon areas Christmas is still called "Midwinter", Jól lasted for 12 days (mostly until January the 2nd) and after the last day of Jól the Germanic new year began.

The custom of placing a Christmas tree in the house is indirectly of heathen origin; in ancient times the people of northern Europe left offerings to the gods under a tree during Christmas, this was done outside because cutting down a tree just for fun was considered to be disrespectful towards nature, like so many other heathen customs this practice was forbidden by the church in most places, but in Germany the people refused to abandon this custom so the church decided to Christianize it; the Christmas tree was now cut down and brought into the house after which it was decorated with angels and stars to include a link to the resurrection of Jesus Christ, though the balls and lights in the tree are also of heathen origin, this custom was originally only performed in Germany but during the 1800's it was adopted by many other European countries.

In Scandinavia the people held a procession during Jól in which they sacrificed the Jól boar to the god Ing (Frey) at the great heathen temple of Uppsala, a Christianized version of this custom still survives in Scandinavia today as St Lucia's Day, the Anglo-Saxons had a similar custom and nowadays the Swedes still eat cookies in the form of a boar during Christmas, Dutch bakers also make marzipan boars or pigs that they sell to their customers during the Dutch Sinterklaas celebration that takes place just before the Christmas period, the people also make boars and billy-goats of straw or ares of corn; most of this local customs probably originate from a single collective heathen festival in which a boar was sacrificed to Frey.

During Christmas some Norwegians leave gifts of food and drink outside for the 13 Jólasveinar, this 13 spirits are believed to bring the harvest, each day one of them arrives on Earth and brings gifts; the first one arrives 13 days before Christmas and every day another one joins him until all 13 are present, after that they will disappear in reverse order, ending on the Twelfth Night of Jól.

In Norwegian folklore there is also the belief that the god Odin secretly listens to people who are holding conversations near a campfire during Jól, he does this to find out if they are happy in their life, he also leaves bread for the poor people.

During Jól it was a custom to give eachother presents, the more presents one gave, the more fertile the year that would follow, in many modern European countries the people still give eachother presents during the Jól period, especially Christmas and the Dutch Sinterklaas celebrations are good examples of that.

The Swedes have the custom of brewing ale at Christmas, it is believed that ale brewed during Jól posesses magical powers and the Swedes often save this drink for special occasions during the rest of the year, the Swedes also drink "Julmust", which is a special type of Christmas beer, and also Sanniklaus, which is the strongest beer in the world with an alcohol percentage of 13.5%, this drink is also only brewed during the Christmas period; the custom of brewing beer at Christmas also exists in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, and many other countries so this was probably an old heathen tradition.

In ancient times the people also performed "Minne-drinks", a Minne drink was a drink to the wellbeing of a person, a god, ancestors, or something/someone else, during Jól it was a custom to drink Minne to the dead.

Another very old Swedish custom of heathen origin is the "St. Stefan's ride", which is held at December 26, it has been named after a Christian saint called "Stefan" to Christianize it but its roots are purely heathen; young men wearing straw costumes or white shirts put on masks or paint their faces black to represent evil spirits, they then mount their horses and ride to a certain river; the wild group of horsemen represent the riders of the Wild Hunt and the custom of painting your face black can also be seen in the Dutch Sinterklaas celebrations where Sinterklaas' funny black helpers originally represented the spirits of the Wild Hunt, the river may have something to do with the belief that water was an entrance to Helheim.

Another very old Swedish custom of heathen origin is the "St. Stefan's ride", which is held at December 26, it has been named after a Christian saint called "Stefan" to Christianize it but its roots are purely heathen; young men wearing straw costumes or white shirts put on masks or paint their faces black to represent evil spirits, they then mount their horses and ride to a certain river; the wild group of horsemen represent the riders of the Wild Hunt and the custom of painting your face black can also be seen in the Dutch Sinterklaas celebrations where Sinterklaas' funny black helpers originally represented the spirits of the Wild Hunt, the river may have something to do with the belief that water was an entrance to Helheim.In Swedish folklore the horseriders are lead by a character called Trond, who is blind and wears a beard, this reminds a lot of the god Wodan, who was believed to lead the Wild Hunt.

A custom similar to that in Sweden was also performed in Germany, but these days it has unfortunately died out in most places there.

The same goes for the Netherlands, but in the Saxon areas in the north and east of the country this tradition has survived until about a century ago; during 2nd. Christmas day (the Dutch celebrate Christmas for two days) the sint-Steffensrit (saint-Stefan's ride) was held in which young men rode through the neighbourhood on horseback and stopped at every inn (herberg) where the innkeeper gave them an alcoholic drink that they had to drink without dismounting their horses.

This tradition (which is mentioned in J.Schuyf's "Heidens Nederland") is believed to be a remnant of an old Germanic ritual where riders on horseback rode through the fields to symbolically fertilize them.

In the German Harz and its surrounding areas there is a legend about a character called "Hackelberg" who leads the Wild Hunt, this name is probably a corruption of "Hackelbernd", who was a legendary oberjagdmeister ("upper-hunting-master") from the 16th century who traded eternal well-being for the eternal right to hunt, although this legend is based on a 16th century hunter its origins are probably much older.

The Swedes also ring bells at the end of the 12 nights of Yule, a custom that is shared by many other Germanic countries; in the Dutch cities of Katlijk and Oudehorne for instance there is the custom of "St. Thomasluiden" in which bells are sounded continuously during the 12 nights of Yule to scare off evil spirits, originally this was also done at night but later this was limited to daytime only, an interesting thing to mention is that the people of Katlijk used to sound the bells on the graveyard and combine it with a party, but this is no longer allowed because it was considered inappropriate, from a heathen viewpoint it makes sense though; after all honouring the dead is an important part of Yule.

Sounding bells during Yule is very old and is believed to date back to Pre-Germanic northern Europe (at least 4000 years ago), though in most modern countries this custom has either disappeared or has been Christianized by connecting it to a Christian saint like for instance St. Thomas in the Netherlands.

Saxo Grammaticus also mentions that bells were used in heathen temples and it is believed that the use of bells in churches is actually a Christianized heathen custom.

There are still many legends that mention how newly made churchbells had to be blessed by priests to Christianize them and how the devil, white women, or heathen gods stole the unsanctified bells and threw them into a lake where they can be heard during the 12 nights of Yule, these stories are very common and there is actually such a lake in my vicinity too.

Another Dutch custom is "Midwinterhoornblazen" (Midwinter-horn-blowing), in which some people blow on big horns that are made of birch and other types of wood; this was originally done to scare off evil spirits but these days it is only a tradition.

Summerfinding:

Summerfinding: During Ostara the people also erected a tree or decorated a pole and danced around it to show their happiness about the "return" of the light, this custom has been preserved in the modern Maytree, Maypole or Questenbaum (see: symbols).

During Ostara the people also erected a tree or decorated a pole and danced around it to show their happiness about the "return" of the light, this custom has been preserved in the modern Maytree, Maypole or Questenbaum (see: symbols). During Jól the borders between the nine worlds were weaker and it was believed that the spirits of the dead from Helheim could enter Midgard during this time, the Wild Hunt (Wilder Jagd) also occured during Jól nights, especially when it stormed; during the Wild Hunt the god Wodan lead the dead over the lands on horses accompanied by dogs in a destructive rage in which people were sometimes kidnapped or killed and their posessions destroyed.

During Jól the borders between the nine worlds were weaker and it was believed that the spirits of the dead from Helheim could enter Midgard during this time, the Wild Hunt (Wilder Jagd) also occured during Jól nights, especially when it stormed; during the Wild Hunt the god Wodan lead the dead over the lands on horses accompanied by dogs in a destructive rage in which people were sometimes kidnapped or killed and their posessions destroyed.