THE LOOMIS FAMILY IN TEXAS

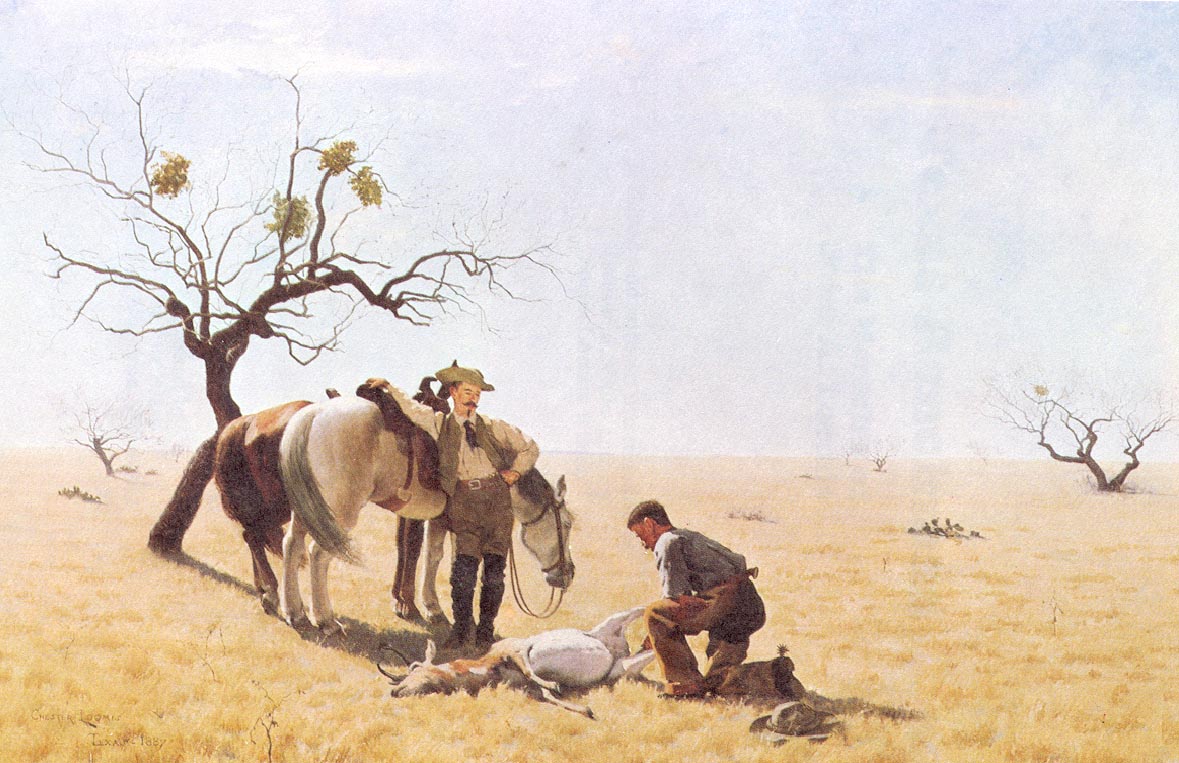

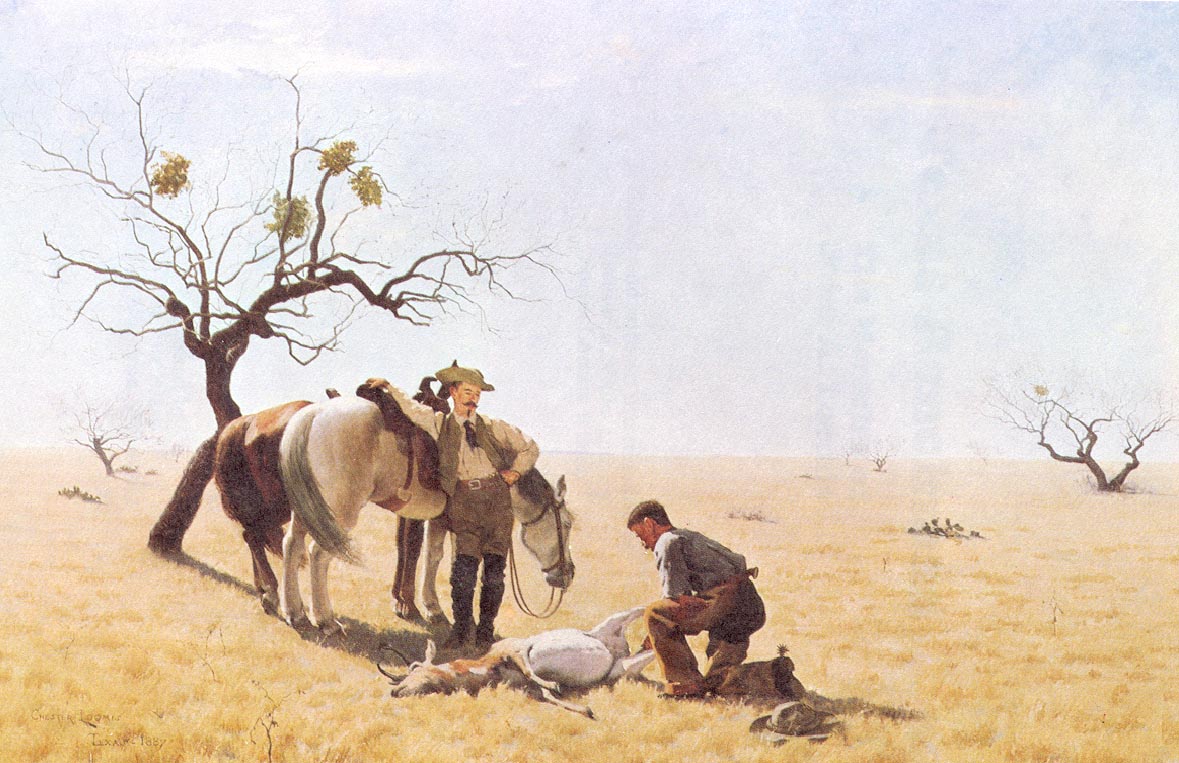

Antelope Hunters, painted by Chester Loomis, Texas, 1887

(Pictures Chester, standing, and his brother John, kneeling)

The text that follows is from the introduction of a book entitled Texas Ranchman, The Memoirs of John A. Loomis. The introduction was written by Herman J. Viola and Sarah Loomis Wilson, daughter of John Loomis. The book was published by the Fur Press in 1982. John Alonzo Loomis was the brother of the artist Chester Hicks Loomis. John and Chester married sisters: John married Abby Helen Dana and Chester married Sarah Sophia Dana.

"I liked this country as soon as I saw it," recalled John A. Loomis, author of Texas Ranchman. A restless man born into a wealthy New York family, Loomis rebelled at the staid life projected for him and somehow persuaded his mother [Lucy Elizabeth Hicks (Ostrander) Loomis] that he would benefit from a trip west before beginning college. Once west he forgot about college. Instead, he settled in Texas, where he eventually launched a massive ranch and real estate venture just as the western land boom was about to collapse. Loomis, however, managed to escape complete financial ruin and kept his hand in ranching until 1915. The memoirs themselves were not written until the 1940s, when the retired rancher was in his eighties. Nevertheless, they are a delightful account of Texas ranch life at a pivotal period in western history, combining humor, readability, and historical insight.

John

Loomis (pictured at left, in a portrait by his brother, Chester, 1899) was

obviously a maverick who enjoyed a good laugh, even at his own expense. He

also much preferred hunting, swapping yarns, and drinking Texas whiskey to

pursuing the usual careers for the youth of his day. As a result, his

memoirs are rich with tales of the chase, ranch life, and the lore of the

West. He relished his association with Western badmen, and they figure

prominently in his story. Black cowboys and soldiers are also

prominent. Loomis himself employed many black cowboys, and his ranch was

near Fort Concho which was garrisoned by black soldiers during the period

covered by the memoirs. About the only group absent from his story are the

Indians, for they had been driven from Texas long before Loomis arrived.

John

Loomis (pictured at left, in a portrait by his brother, Chester, 1899) was

obviously a maverick who enjoyed a good laugh, even at his own expense. He

also much preferred hunting, swapping yarns, and drinking Texas whiskey to

pursuing the usual careers for the youth of his day. As a result, his

memoirs are rich with tales of the chase, ranch life, and the lore of the

West. He relished his association with Western badmen, and they figure

prominently in his story. Black cowboys and soldiers are also

prominent. Loomis himself employed many black cowboys, and his ranch was

near Fort Concho which was garrisoned by black soldiers during the period

covered by the memoirs. About the only group absent from his story are the

Indians, for they had been driven from Texas long before Loomis arrived.

While the memoirs are filled with tales of adventure and derring-do, they revealed relatively little about the author's private life. Nevertheless, Loomis was a family man. In 1888 he married Abby Helen Dana, whose sister was married to his brother Chester. A year later the young couple had a daughter, Sarah; she was followed three years later by a son, whom they named Chauncey.

Perhaps Loomis ignored the domestic side of ranch life because he found it rather ordinary. His daughter Sarah certainly did not consider ranch life very romantic. "My recollections of life on the ranch include no gun dueling, sheriffs, or long hunting trips," she recalled years later. "We had become quite civilized in the nineties [1890s] when I came along. We had cowboys, cattle round-ups, horses for driving and riding--chickens, a herd of Jersey cows for milk and cream, an irrigated garden, and assorted barn cats." The only shooting incident occurred when the cook and one of the cowboys had a fracas over a horse. Neither one was seriously injured. "On the whole, life was quiet, rather like an English country house or a southern plantation," she remembered. A governess stayed with the children each winter and served as their teacher. The ranch boasted a fine library that included many English writers like Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott, and such classics as the Iliad and the Odyssey. Mrs. Loomis often read to the children on hot summer afternoons when they would sit on the lawn in the shade of a tree.

The only excitement involved trips to town. The nearest post office was in Paint Rock, eight miles away and an hour by carriage. Someone made the trip once a week. San Angelo was the nearest town of any size and it was twenty miles away from the ranch, which meant almost a four-hour buggy trip. In the winter, trips to town required protection from northers which could descend suddenly, so the children would be wrapped in wolf skins and hot hot bricks for their feet. In the springtime, cloudbursts and hailstones might greet the travelers, while in the summer they had to cope with burning wind and sun. No matter. "We drove a good team of horses, usually attached to a covered hack. Father was fond of good horses."

John Loomis was also somewhat restrained in his description of the Ostrander & Loomis Land and Livestock Company, a venture which must have brought back painful memories. Painful though it may have been, this episode is important because it illustrates so well the financial collapse that occurred on the Great Plains in the 1880s. Cattle raisers throughout the area had enjoyed phenomenal success in the early part of the decade, a success that encouraged widespread speculation in stock raising. This, in turn, led to the overgrazing and overcrowding of rangeland. John Loomis and his half brother Welton Ostrander, (son of Lucy Elizabeth Hicks Loomis by her first marriage), had the misfortune to launch their company in 1885, the very year that the bubble began to burst. According to the promotional pamphlet, the Ostrander & Loomis Land and Livestock Company offered investors the opportunity to obtain $300,000 in bonds that would mature in twelve years and provide a six percent annual return. Not only would investors realize their annual interest payments, but also they would share in the projected growth of the capital assets. These would be considerable. As of April, 1886, the company owned 44,895 acres of land, 3,000 sheep, 500 horses, 60 head of cattle, and 3 thoroughbred stallions. The company's net worth was $516,850.00. After ten years, the company expected to have a net surplus of $1,708,054.00 "over and above paying off...[the] bonds and interest." Having sold off the sheep and cattle in favor of horses and mules, the company's assets would then include 75,00 acres of land, 1,820 road mares, 1,964 horses, 1,300 Norman mares, 4,160 mule colts, 30 jacks, and six stallions. "What other business, the partners boasted, "can make so good a showing and be so sure and safe, since all the investments are either in land or in young stock, both of which go on augmenting in value, unlike merchandise, which depreciates unless soon sold?"

The young entrepreneurs must have soon regretted their unbounded optimism. The winter of 1885-86 was cold and blustery; the summer of 1886 hot and dry. It soon became evident that there were too many animals for the available grass. By the fall of 1886 experienced cattlemen were dumping their livestock on the eastern markets. Steers worth $30 the year before were going begging for $8 or $10. Those ranchers who sold, even at such low prices, were wise. The winter of 1886-87 was on of the worst in western history and killed most of the livestock roaming the open range. As a result, the large land and cattle companies, including that of Ostrander and Loomis, disappeared soon after.

What did not disappear was the massive stone mansion that Welton Ostrander built for his family on high ground overlooking Kickapoo Creek. It still stands as a stark monument to the speculative zeal of the 1880s (see pictures above: at left is the ranch in the 1880s; at right is the ranch in 1999.) The Ostranders lived there for only a year, although a daughter stayed longer entertaining her mother and various eastern relatives before she finally returned to Syracuse in 1888. Thereafter, the big house stood empty for some 30 years looking tragic and ghostly and gathering legends that have survived to this day. The December 1956 issue of Coronet magazine, in fact, featured it in an article entitled "The Strange Mystery of Paint Rock." The author believed he had finally solved the "mystery" of the abandoned ranch house, declaring that Welton Ostrander was an English investor who had to leave Concho County one step ahead of the Texas Rangers coming to evict him as a result of newly enacted legislation against foreign investors. He suggested that Ostrander was wanted by the Syracuse police and so could not risk being apprehended by the Rangers. As a result, he had to abandon his property and flee Texas. The simple truth, according to John Loomis, was that Welton's wife was bored with western life and insisted they move back to the east.

John

Loomis was left with two stone homes, (Ostrander ranch, above, and Silver Cliff

Ranch, pictured at right in the 1880s), one hundred cattle, a

few horses, and a family to support. He borrowed money to buy Hereford

cattle, and he cultivated three farms, totaling about one thousand acres, to provide

feed. Although he continued to run cattle until 1910, his efforts were

only marginally successful. While ranch life continued much as before,

market prices were subject to adverse tariff laws and weather. It was also

a sign that times had changed. "Farmers, or "nestors" as

they were called, were settling all around the ranch," he recalled.

"The antelope were gone. We no longer heard the coyotes and owls at

night. The whole character of the region had changed and the wild charm

had vanished forever."

John

Loomis was left with two stone homes, (Ostrander ranch, above, and Silver Cliff

Ranch, pictured at right in the 1880s), one hundred cattle, a

few horses, and a family to support. He borrowed money to buy Hereford

cattle, and he cultivated three farms, totaling about one thousand acres, to provide

feed. Although he continued to run cattle until 1910, his efforts were

only marginally successful. While ranch life continued much as before,

market prices were subject to adverse tariff laws and weather. It was also

a sign that times had changed. "Farmers, or "nestors" as

they were called, were settling all around the ranch," he recalled.

"The antelope were gone. We no longer heard the coyotes and owls at

night. The whole character of the region had changed and the wild charm

had vanished forever."

Nevertheless, he was still anxious to hold on to the land, so he decided to give up ranching and try his had at farming. Since the local farmers seemed to be merely "getting by" on their small farms and he was always one to do things on a grand scale, he cultivated several thousand acres at once in order to make a financial killing. He did this even though many friends advised against it and despite the lessons learned by the Ostrander & Loomis Land and Livestock Company. He bought a steam tractor and disc ploughs, hired a first-rate foreman, built two cotton gins, and erected houses for tenants. The first year was dry, and he barely made expenses; but the next year was wet, and twenty-five hundred acres of cotton grew like magic. Indeed, the cotton plants were laden with bolls. They were also laden with boll worms which ruined the crop. What the worms missed was wiped out by a rainstorm. Loomis figured he lost $200,000 that year. As a result, he was in a trading frame of mind when the opportunity came in 1915 to exchange the ranch for a hotel in Muskogee, Oklahoma, thereby ending his thirty-year career as a Texas rancher.

The years that followed were largely anti-climactic for the ex-rancher. His marriage broke up about the time he gave up the ranch, but he and Abby were not divorced until 1924. By then their children were grown and had gone their separate ways. When the hotel business proved even less rewarding than ranching, Loomis returned to Texas with a new wife, Susan Alkman. Even in old age, however, he remained restless, energetic, and visionary. He devoted his declining years trying to develop the hunting and lumbering potential of a massive tract of wilderness in the mountains of northern Mexico. This venture, too, proved profitless.

It was a request from the Dallas Morning News for stories from him about the early days of Texas ranching that inspired Loomis to write his memoirs. Although now in his eighties and virtually deaf, he approached his final project with typical zeal and enthusiasm. Indeed, time may have robbed him of his hearing, but it had obviously not dulled his mind for the result is a delightful account of Texas ranch life at a pivotal period in western history, combining humor, readability, and historical insight.

Unfortunately, John Loomis did not live to see his memoirs published for he died on October 19, 1949, just two months short of his 91st birthday.