Label History

The evolution of names is itself interesting. Dole currently uses its own name, but also sells secondary lines under the "Cabana" or "Cabanita" label. Dole's banana business has its roots in the old Vacarro Brother's Standard Fruit & Steamship Co. That firm originally marketed using "Cabana" and "Tropipac" labels, with the first name reserved for the new (in the 1960's) disease-resistent Cavendish fruit and the second for the declinning supplies of the better tasting, but disease-prone Gros Michel bananas. After Gros Michel exports ceased, the Tropipac label continued in use as a second brand. When Hawaii-based Castle & Cooke, then the owners of the famous Dole Pineapple empire, acquired Standard Fruit in the 1970's, they chose to market with the better known Dole brand, pushing the old Cabana name to the second tier, and retiring the Tropipac name. Today's Dole is an independent firm based in California, the world's largest seller of fresh fruit and produce.

It may seem strange to think of banana labels in political terms, but the little labels do, in many cases, tell a story clothed in controversy. In my favorite's section you will see Misha, the Russian Bear, who never made it to a banana because the U.S. pulled out of the 1980 Summer Olympics. Residents of European Community nations see bananas with labels from Caribbean and African countries which have enjoyed protective quotas against other world producers-- part of the battle that recently led the World Trade Organization to support "free trade" which favors big multi-national growers, and Latin American nations.

We have also seen "Fair Trade" banana labels like Max Havalaar, Fairnando and Transfair, that represent European attempts to promote "Solidarity" with small growers in many different parts of the world.

Many label collector's frown at Chiquita labels, largely because of their long-standing uniformity. But no banana company has a longer, more fascinating history than this decendent of the old United Fruit Company. Historically UFCO had somewhat of a split personality. It pioneered development in many parts of tropical America, built railroads, provided model company towns and quality health care, established schools and agricultural research centers, and provided full-time employment to thousands. On the other hand, it cultivated dictators, bought politicians, suppressed unions, and became a monopoly in the U.S. market to the extent that anti-trust action eventually forced it to sell off part of its empire.

Today's Chiquita is not the all-powerful company of old, but it is still viewed with suspicion by many. When Chiquita celebrated its 100th Anniversary in 1999, it issued special commemorative labels for the occasion. They were widely used on fruit in Europe, but never made it into the U.S. market-- an apparent management reaction to bad publicity following a Cincinnati newspaper expose.

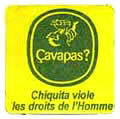

The E.C.- W.T.O. controversy mentioned above also led to one of the strangest banana labels ever seen-- a French-language protest label that was illegally placed on Chiquita fruit in Belgium (and possibly elsewhere) by local activists.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||